Ji hlava International Documnentary Film Festival

Le chant du Styrène

Waste in Time and the Radioactivity of Objects

Cultural scholar Esther Leslie reveals the vexing temporalities of contemporary types of waste as it unsettles the socioeconomic logic of extraction and decay. Plastic fabrics and electronics molecularly molded from fossil hydrocarbons and rare earths, together with the multiple toxic byproducts of their life cycle, suggest a new history of the synthetic and the natural.

In 1957, Alain Resnais and Raymond Queneau made The Song of Styrene, an advertising film for the chemical firm Péchiney. It shows, in reverse, the procedure for the manufacture and processing of colorful styrene items, including a red bowl. It presents the many stages of producing a plastic material and working it into goods—molding, beading, extruding, stretching, coloring, and heating. There are references in Raymond Queneau’s screenplay to life, liveliness, and the process of giving birth: the birth of an object from a mold, the birth of hydrocarbons, these vivacious and turbulent granules. Human hands extract objects from molds like a midwife extracts a baby. The building block of plastics is polymers, synthesized from chemicals extracted from petroleum, as well as coal, air, lime, fluorspar, and salt. Polymers are constellations of long, chain-like, carbon-based molecules that can be shaped when warm. Polymer makes plastics: polymer, polymer, polymère, many mothers, is a pun made by Queneau. As the film works backwards, it makes origins explicit: the beginning of the bowl in the seas, posing a common origin with something that became human life. These origins are obscure: somewhere in the sea, among the oil of fish from millions of years ago, are wasted, dead organic matter. As masses of coal undergo firing, the film text muses:

Does the oil come from masses of fish? We do not know too much or where the coal comes from. Is oil coming from plankton in labour?

Mysterious common origins unite that which is conceived as natural with that which is conceived as artificial, indeed emblematizes the artificial. The bowl is a “solid cloud,” for this is a body that, like clouds, could be molded into any form. “In new materials these obscure residues / Are thus transformed.” Waste becomes new life, an unimaginable proliferation of new forms.

Plastic is a “material of a thousand uses,” as the inventor of Bakelite, the first truly synthetic resin, dubbed it in 1907. Once upon a time plastics had been solely made by nature. Then natural substances were coaxed, through human invention, into forms. Bakelite came close to the body and mingled in the senses; from it came the radio sounds that caressed the ear, it entered the mouth as a smoking pipe, through telephone conversations it was whispered into; this browny plastic became intimate with the early twentieth-century consumer. When its patent expired, Catalin appeared, in 1927, with the added bonus of a range of colors. What began as limited in color—the white of ivory, the brown-black of tortoiseshell, the orangey-gold of amber—fanned out into a rainbow. In the 1830s the most spectacular transformation had begun, as colors burst out of the darkness of old dead matter they met well with these new materials, for color and plastic were twins of the laboratory. Color, like oil, came from a waste product. A waste product from black coal, its tar the foundation for an entire spectrum of colored dyes. The epoch of mass consumerism came in a rainbow of colors. Nature was outbid in the laboratory for the creation of flexible and moldable materials that could appear in any shape and any color.

By the early years of the twentieth century plastics were in dining rooms and parlors, bathrooms and kitchens, playrooms and gardens, factories and offices, on the battlefield and in the cinema. There was rayon and viscose, Formica and formaldehydes. There was Perspex and polystyrene, polyethylene, acrylic, and melamine. The names clunked from the lips like new hexes. Familiar and cooked-up materials seemed flung together in magical rituals that produced new substances out of which old objects—buttons, combs, door knobs, bangles—might be formed, and new ones—plugs, light-fittings, telephones—were given shape. It was the waste of the oil-refining process that produced Tupperware.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Synthetic materials promised to increase the quality and quantity of life. DuPont’s slogan, devised in 1935, resonates with this: “Better Things for Better Living [...] Through Chemistry.” Adaptability is a key quality of synthetic materials; after the war, in Germany in particular, where making substitutes was a high art and one associated with the war years and the search for Ersatz materials, the first task of manufacturers, advertisers, and chemists was to reform the image of plastic, which was regarded as inauthentic, degraded. The economy demanded that surrogates climb in value: the traditional to be diminished in face of plastic substitutes. Turned inside-out, plastic was remolded as the very substance of democracy.See Andrea Westermann, Plastik und politische Kultur in Westdeutschland. Zurich: Chronos Verlag, 2007.

“Whether Hannelore, Lilli, Hella or Isabella / Life is led more simply, beautifully and more untrammeled with Acella / No dirt, no dust and not a blemish / One wipe and everything has vanished,” goes the 1950s jingle. Acella, a soft-plastic fabric of PVC—a modern fabric for modern people—eliminates waste through its very presence. Floor coverings, window drapery, furniture, toothbrushes, plastics found their way into domiciles and the governmental corridors of power alike, an indication of their essential anti-hierarchical leveling. Such materials befit a new forward-facing environment. A material bent by forces itself exerts a powerful social force, one connected to waste—for if all this modernity, this new economy is to work, it must be based on squander, on waste, on endless renewal, on the caprices of fashion, on obsolescence, on consumption without end. In time, all of this, all this newness that is to be kept ever-new, will be remaindered. It is part of its economic logic; it is also part of its nature. Like everything, it becomes the past.

The past comes to us in strange colors and odd substances, some embraced their modernity, while others claimed and still claim to imitate the natural world. The past appears to us as odd shapes that were once so intimate with someone’s fingers or hair, their voice or ear. The magic that was proclaimed to constitute the new now lingers as a dusty magic or charm that adheres to the relics of the past, as the Surrealists knew well. An old, dented PVC doll, discolored and warped, a melamine ashtray scratched yet still cheerfully bright; that which was so of its moment slips out of its moment and becomes itself a residue that occupies the same amount of space, emits the same intensity of light, and yet is displaced. It has not become a memory, but a stumbling block, a scandal. The unnatural wears itself into the landscape and juts out at us, not because it is curiously new, but rather curiously old, out of time. That which promised a signal of more life, of a better life, becomes fragments for a history of non-life, becomes so many residues that continue to exude something, a minimal signal connected to memory—or it exudes something worse, more tangible, a leeching that is harmful, a crumbling like that of asbestos, fatal.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

What residues? What by-products? What toxicities? What lingers on? Since The Song of the Styrene around 8.3 billion tons of plastic has been produced, and much of that now occupies the oceans or landfill. Resnais and Queneau gesture at lives and life cycles in The Song of the Styrene with analogies made between an individual human birth and the life of a plastic bowl, but they also indicate the birth of a species and the birth of a “new nature,” both emergent from the sea. One, the species “life,” a product of teeming life in the depths, the other, “new nature” in oil, coal, and plastic, a product of all of that life’s death. Time figures—eons: a long time since their origins, and an even longer time until that which is a product of death (oil-based plastics) dies again, or, more accurately, wears out, breaks down; that time may never come.

Birthing in the film occurs through a mechanical dynamism, an almost autonomous action of material and machine in conjunction, with workers featuring only as occasional walk-ons. There is a contradiction between, on the one hand, the sleek, placeless machinery, the industrial plants that are distributed across the world all operating in the same way, and the smooth products they make, which are also distributed throughout the world and always look the same, and, on the other, the references toward the end of the film to the places of extraction and the specific ingredients of plastic manufacturing such as the Indonesian shrub storax (or snowbells) crucial to the material, as well as the oil, which is found—so Queneau states—nearly everywhere from Bordeaux to states in Africa. And from these specific details of matter and place, viewers are made aware that the structure into which the red bowl of The Song of the Styrene arrives is one of geopolitical distribution, of economies that straddle the world, from France to Indonesia to Africa, and that these function within the contexts of colonialism and decolonization.Edward Dimendberg, “‘These Are Not Exercises in Style’: Le Chant du Styrène,” October, no. 112 (Spring 2005), pp. 63–88. The firm that owned the red bowl factory, Péchiney, had plants in Cameroon and French Guinea, and in that same region the French petroleum industry was extracting reserves, until nationalization followed independence in various countries.

The red plastic bowl is there at the start of the film gleaming, as are the plastic ladles and rainbow tags, all newly born. It is old for us now: is it still floating in the seas or in landfill? How scathed is it? These plastic forms—which exist in time but exude a certain timelessness, as is the wont of plastic forms—are deconstructed through the course of the film’s thirteen minutes. The plastic objects are taken back to an original moment, original matter, out of which, going forwards, the magic of science and technology will conjure a bowl, or a plug, or a spoon.

Rare Earthenware (2015) by Unknown Fields is another film-in-reverse that follows products to their origins. Rare Earthenware tracks rare-earth elements—such as terbium, europium, and neodymium—back to their extraction. These are used in electronic devices and so-called green technologies that promote renewable energy or supposedly mitigate environmental damage: compact fluorescent bulbs, electric-car batteries, solar panels, wind turbines. The film documents their passage from container ships and ports across the world to wholesalers and factories in China, and eventually back to the banks of a barely-liquid tailings lake in Baotou, Inner Mongolia, where the refining process of the minerals takes place.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The ten square-kilometer tailings lake is comprised of a constant flow of sludge, a radioactive clay that has been shed by the city’s mineral-refining factories. Tailings are the materials remaining once an ore has been stripped of its economically valuable parts. This waste settles in a pond, in mud, preventing the fine tailings from floating on the wind into populated areas and harming human health; any animals attracted to the seeming pond would not live long. Under a certain light this black mire might exude a lustrous gleam like the plastic of a smart phone’s casing, the sludgy lake it surrounds is the other side, the liquid crystal touchscreen; the side which monitors the changes in electric state on the screen, composed of these rare-earth minerals and metals, highly conductive and optically transparent ones, easy to deposit on the glass as a film.

The landscape’s minerals are splintered into tiny parts and distributed on the surface and inside of a box that is never supposed to be opened, at least until its life’s end, perhaps not even then. From under the ground, from immense cavernous holes in the earth, from brown rock and mud, smashed and grabbed from the crust, elements take up residence inside the glossy pebbles, the black boxes, the smooth white slabs, the rose-gold gewgaws. Where masses of these minerals are mined, in environments prepared to accept the hazardous and toxic processing required, the rainwater turns murky from the interminable coal dust of the power stations that day and night process compounds for polishing touchscreens or coloring glass. This smart world of light and polish is an elemental one, binding chemical elements for its affects. The film provides statistics: there are eight rare-earth elements in a smartphone and it produces 380 grams of toxic waste in the course of its manufacture, a laptop generates over one kilogram.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

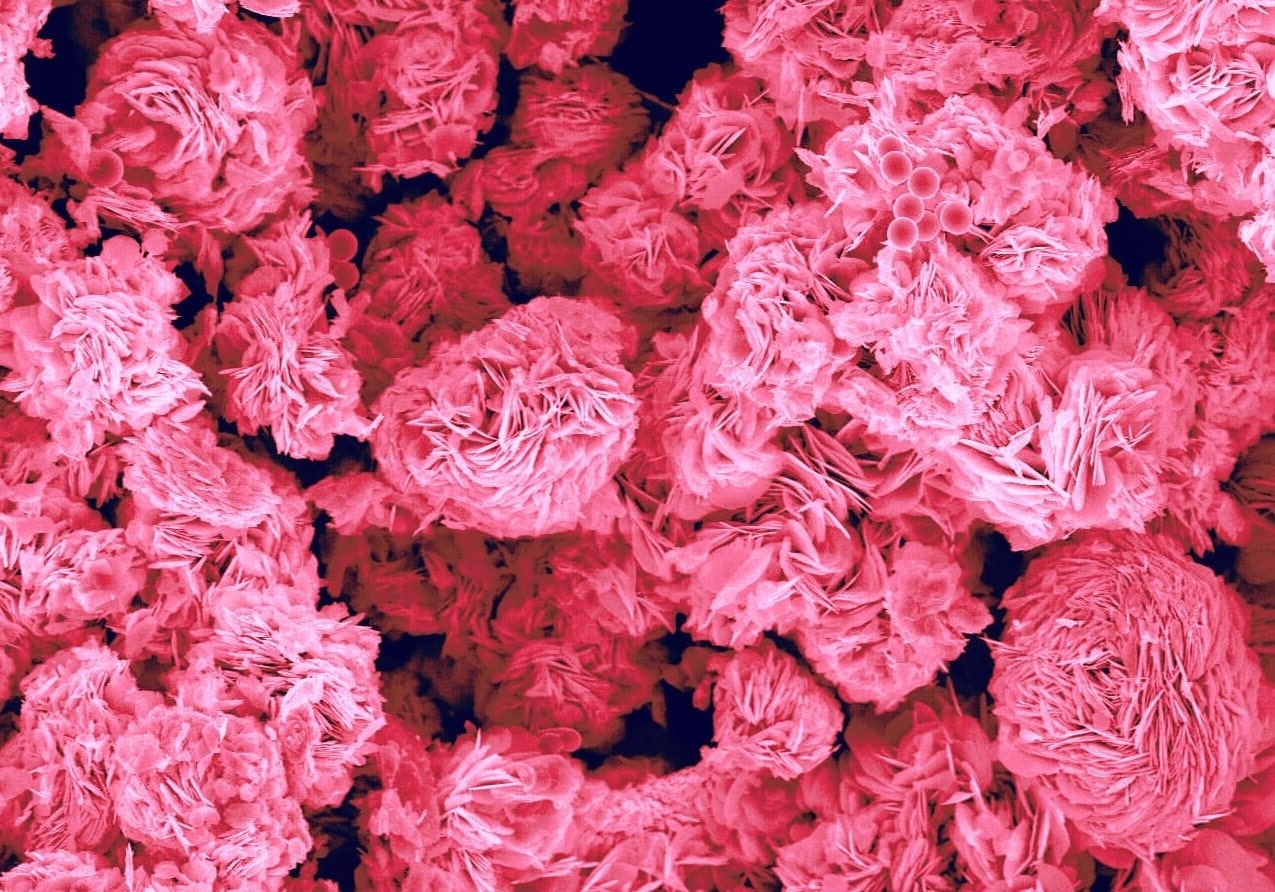

Together with Kevin Callaghan, the filmmakers used mud from the lake to craft a set of ceramic vessels. Each is sized in relation to the amount of waste created in the production of three items of technology – a smartphone, a featherweight laptop, and the cell of a smart car battery. In their reference to the Chinese tradition of producing—and exporting—valuable porcelain, as well as in their manufacture of irradiated objects whose atoms have half-lives that will likely outlast ours, the vessels evoke a tangle of thoughts about waste: about recycling, beauty, the irreducible, the timescales introduced by new processing, the effects this has on the environment and how we might think about that, fatefully, in terror at new prospects of sublime devastation, and delightedly, in terms of new aesthetics, the new possibilities of objects that are recognized as more active than ever before, even if only radioactive. They are active because we are attuned now to how much these objects build relations between us. Active because we are sensitive to the distribution of agency. Active because like humans these are amassings of promise, things with the capacity to delight or to do harm.

This specific waste, the toxic waste of mineral processing, is rarely redeemed. The gesture of making it into pots is a perverse one, possible only within the remit of art or cultural politics. This poisonous waste is not like the waste of the seas that, over impossibly long times, made petroleum, which, in turn, could make plastic, a substance that would, in time, return to those seas and deep into the earth where it too exudes toxins—this muddy waste is a more direct process. It is waste that remains, for the most part, from its start to end irreducibly waste. It does not pass through human hands. Its life, its radioactive half-life, is long, endlessly long. But its existence is not measured in human terms, this is residue, its valuable part—the useful minerals—has traveled the world, but even the value of that part is limited. Soon the mainly plastic bodies, or outer shells, of phones, laptops, batteries, bulbs, housing the valuable minerals, will be discarded through constant upgrades, and the whole plastic body and mineral core will find its way to landfill or the seas, generating a new category of waste—e-waste. The rare-earth minerals will return to the earth, pressing into it, but this time leaking toxins and contaminating it; some people might dream of recovering tiny quantities of valuable minerals from devices, some might one day make a business of it.

The Song of the Styrene alluded to the Song of the Sirens—a beckoning call by a number of harpy-like women whose classical names are as evocative as those names of plastics: Peisinoe, Aglaope, and Thelxiepeia alongside Parkesine, Alkathine, and Galalith. Theirs was an enchanting melody sung to lure sailors into shipwreck; to respond to that song was hazardous. Hazardous too, then, is the call of plastics, that they would entice us into their world, make us bring them through their birth into our world, so that we might share it. Hazardous too are the toxins they produce as they decompose in the waters and landfill—and hazardous too is the exposure to toxicity that poses new levels of pursuable risk to the world. This plastic, that little red bowl that promised so much, has generated new contours of waste whose lifespan may be limited but the effects of which last an eternity, though if we are lucky we may find out that they can succumb to a slow digestion by bacteria, so that new forms might be recycled from the disintegrated chemicals. Plastics propose a non-time of newly born and never sullied existence. It ends floating on the seas—although “end” may not be accurate, for we operate still with the idea of a certain reversibility. A Canadian company called Upcycle the Gyres Society (UpGyres) works under the premise that waste plastic in the oceans is an extractable reserve that can be made self-sustaining, profitable, and have a positive environmental impact in the “blue-circular economy.” The proposal is a reversal: “Because plastic comes from oil, processing technology already exists to transform these oceanic plastic deposits through pyrolysis back into oil and into low sulfur fuel for energy and transportation.” Other plastics can be chemically recycled to make virgin plastics, collected by robots that appear to share the same quality of life.

UpGyres offers to extract plastic deposits with bio intelligent and biomimetic robots. The advantage of using biomimetic robots is that they will blend with marine life; will be able to shelter themselves from storms and hurricanes; locate, track, pursue and actively collect as well as passively extract deposits of macro, meso and micro plastics from the surface and water column of the global ocean.José Luis Gutiérrez-García, “The Case for Upcycling the Gyres,” The Maritime Executive, September 10, 2017.

UpGyres is still fundraising for its project to exploit this new material for extraction. The tailings lakes across the world, and in its poorest parts, might offer themselves up as a resource in time too, a resource for more than just art projects. It is as if, after all of this, we can turn back time and make something better: take another route in which the mountains and islands of waste were not permitted to grow, or that we could make of them things of beauty that were no more harmful and threatening than the vision in a painting of cataclysm or natural fury.

Everything is waste. In time, everything is wasted. Nothing is waste. Over time, nothing is wasted. Any look into a rubbish bin is an image of potential beginnings—for waste awaits only a new extraction. Waste is a resource. Perhaps there are endpoints though. That we might reach the waste that can never be re-assimilated, is too dense a concoction of toxins and things that harm life. Then that waste becomes waste that is usable, but not for us. Against us perhaps, or against those who are poor, who are always sited near the toxic remnants. If not for us, then, for what instead?