China’s “Blue Territory” and the Technosphere in Maritime East Asia

Beyond the contentious geopolitical edifice of the South China Sea lies a mosaic of technological and ecological manipulations of land and sea interfaces that define how the area’s many contests are negotiated. Political scientist Andrew Chubb maps this complex space, tying together security, land rights, information technology, historical geopolitics, and the creation of artificial islands that construct it.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Human techno-political challenges to the land‒sea divide are perhaps nowhere more apparent than in maritime East Asia. Here, the concept of “blue territory” displaces the maritime commons, while underwater reef ecologies are transformed into gleaming military outposts, and satellite communications advance land-based claims to sovereign jurisdiction over once-ungoverned waters. This article will examine how the expansion of legal, logistical, and informational technologies have problematized the very distinction between land and sea in the world’s most contested maritime spaces.

TERRITORIALIZATION OF THE OCEANS

In July 2016, an international tribunal constituted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) handed down its ruling in an arbitration requested by the Philippines over China’s actions in the South China Sea. Alongside a meticulous catalogue of Beijing’s breaches of the Convention, the ruling’s key significance was to set stringent criteria for establishing a maritime land feature’s legal status as an “island” entitled to expansive jurisdictional rights over the surrounding waters. On the surface, the legal landmark sharply circumscribed the potential scope of sovereign claims over maritime space. But it also highlighted the paradoxical territorialization of maritime space under the “global constitution for the world’s oceans.”

Throughout the twentieth century, while international law gradually was chipping away at state authority over the earth’s landmasses, precisely the opposite was occurring at sea. In Bernard Oxman’s memorable terms, the “territorial temptation” of the world’s nation-states “thrust seaward with a speed and geographic scope that would be the envy of the most ambitious conquerors in human history."Bernard Oxman, “The Territorial Temptation: A Siren Song at Sea,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 100, no. 4 (2006), p. 832. The displacement of the doctrine of mare liberum, defended in recent centuries by successive maritime hegemons, began with United States President Harry Truman’s assertion of sovereign rights on its “continental shelf” in 1945. Far from objecting to this unprecedented, unilateral expansion of state jurisdiction at sea, other major maritime powers quickly emulated it.

Behind this sudden, breezy betrayal of the long-treasured “free seas” lay the prospect of hydrocarbon exploitation made possible by new offshore drilling and extraction techniques. In the first Law of the Sea Convention signed in 1958 the state parties agreed – absurdly in hindsight – to grant each other exclusive rights to the seabed out to whatever distance “admits of the exploitation of the natural resources.”United Nations, “Convention on the Continental Shelf, 1958,” (http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/8_1_1958_continental_shelf.pdf). Under this formulation, the extent of sovereign claims to seabed resources was limited only by the rapidly developing oil and gas extraction technology.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The UNCLOS concluded in 1982 at Montego Bay, Jamaica, is the defining expression of the territorialization of maritime space. Although the 107 state governments sensibly agreed to limit the previously infinite continental shelf claims to 650 kilometers, they also assigned themselves and each other sovereign authority not just over the seabed, but also the resources of the water column out to 370 kilometers from the homeland’s nearest basepoint, including islands. In so doing, they subjected nearly 50 per cent of the world’s oceans to land-based claims of state jurisdiction. Other governments were understandably eager to join the regime, and today 157 nation-states are parties to the UNCLOS.

This carve-up of half the planet’s oceans was not simply a naked grab for power and oil; other goals of the process included allotting responsibilities for environmental protection and avoiding “tragedies of the commons” through orderly, regulated exploitation. This may have been the tradeoff that induced civil societies to agree to such an enormous expansion in state authority.Oxman, “Territorial Temptation,” pp. 844‒45. However, beyond the prospect of international legal opprobrium of the kind suffered by China following the 2016 arbitration, states’ responsibilities under the Convention lack an effective means of enforcement. The new sovereign maritime rights, by contrast, faced no such issues, for every state party stood ready to enforce those. Indeed, as Oxman notes, they were quickly understood in “quasi-territorial terms.”Oxman, “Territorial temptation,” pp. 839‒40. This was nowhere more so than in China, where areas subject to its resource rights claims came to be regarded as “blue territory.”

CHINA’S “BLUE TERRITORY” CONCEPT

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) – presumptive successor to a dozen great continental empires – took some time to recognize the new opportunities and challenges presented by the carve-up of the world’s oceans. By 1996, however, when it ratified the Convention after a fourteen-year delay, PRC maritime agencies had become acutely aware of the “gradual territorialization” (逐步国土化) of vast expanses of ocean that was by now in full swing.See Chapter 1 of China’s Maritime Agenda for the 21st Century, a programmatic document released immediately prior to its ratification of the Convention. Zhongguo Haiyang 21 Shiji Yicheng (China’s Maritime Agenda for the 21st Century). Beijing: State Oceanic Administration (SOA), March 1996 (http://sdinfo.coi.gov.cn/hyfg/hyfgdb/fg8.htm) (accessed December 1, 2016). The PRC appears to have viewed the territorialization process in generally positive terms at that time. Indeed, so sanguine were the Agenda’s authors that they even described UNCLOS as “beneficial to breaking maritime hegemonism” – a glowing accolade within the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideological system. See China’s Maritime Agenda, Chapter 10. China’s ratification of the regime in May 1996 set in motion a succession of technical and policy responses that have imposed legal, organizational, and physical layers of land-based rule over the disputed South and East China Seas.

The chain of Chinese policy reactions began with the enactment of a variety of new legal instruments – notably the 1998 Law of the People's Republic of China on the Exclusive Economic Zone [EEZ] and the Continental Shelf – that gave unprecedentedly specific, concrete form to China’s claimed sovereign rights at sea. As Isaac Kardon notes, this burgeoning body of maritime laws, regulations, and ordinances was crucial in “processing the various new rights and interests created by China's accession to UNCLOS.”See Isaac Kardon, “China’s Maritime Rights and Interests: Organizing to become a Maritime Power,” paper presented at the China as a Maritime Power Conference, Center for Naval Analyses, Washington, DC, July 28‒29, 2015 (https://www.cna.org/cna_files/pdf/china-maritime-rights.pdf). By the turn of the century, these sweeping, once-amorphous claims were rapidly hardening into a concept of “blue territory.” As the Minister of Land and Resources Zhou Yongkang stated in a 1999 speech:

[…] according to UNCLOS and our country’s claims, we possess around 3 million square kilometres of waters under administration. Of course, there is a significant area that is in dispute, which is to say, there is a long way to go and much difficult work to be done to genuinely roll out our maritime undertakings over 3 million square kilometres of blue territory.Zhou Yongkang’s speech is printed in the State Oceanic Administration’s (SOA), Zhongguo Haiyang Nianjian (China Ocean Yearbook) 1999‒2000. Beijing: Haiyang Chubanshe, 2000, pp. 10‒11. Hereafter ZGHYNJ.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

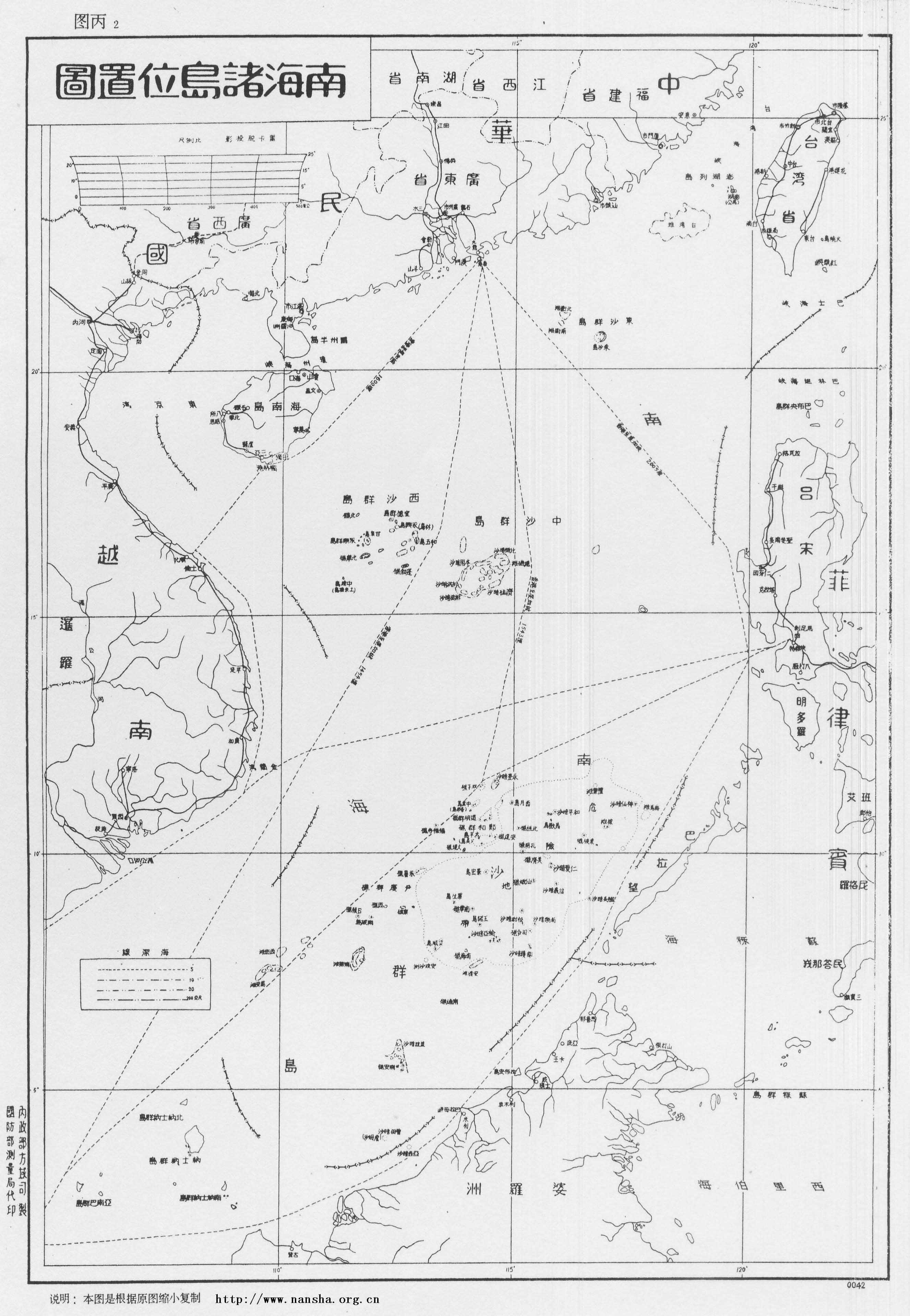

China’s claims to islands in the South China Sea had been manifest in the now-infamous nine-dash line map since the 1940s. But the map, titled Location Map of Various Islands in the South China Sea (南海诸岛位置图), contained no hint of any claims to particular maritime spaces – let alone the entire area enclosed by the line. The UNCLOS offers no support for such an expansive reading of the line; indeed the arbitral tribunal emphasized just the opposite. Yet, ironically, the increasingly territorialized quality of China’s maritime claims – and its approach to prosecuting them – is very much a product of the UNCLOS era.

The UNCLOS-inspired reification of China’s maritime claims into domestic legal instruments prompted the creation of new law enforcement organizations. This in turn produced new technologies of enforcement that have redefined the rules of disputes at sea, at least in maritime Asia. The China Marine Surveillance (CMS) force, established in 1999, was given the task of rolling out “comprehensive administration” in all areas subject to PRC jurisdictional claims. Major allocations of central funds in 2000 equipped the new agency with a fleet of large long-range, high-endurance – but largely unarmed – oceangoing patrol boats and aircraft.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

These systems for achieving a constant patrol presence, greater maritime domain awareness, and the necessary personnel and logistical support, took several years to develop. But by 2006 the agency was ready to launch its “regular maritime rights defense patrols” across disputed areas.Initially the system was introduced in the East China Sea in June 2006. Once its feasibility had been proven there, the CMS extended the scope to cover the Yellow Sea and the northern part of the South China Sea from February 2007. Nine months later, this was expanded again to include the southern part of the South China Sea. Thus, by December 2007, the regular patrol system theoretically covered all of “the 3 million square kilometres of waters under China’s administration.” See Qian Xiuli, “Woguo jianli quan haiyu weiquan xunhang zhidu, 300 wan pingfang gongli guanxia haiyu naru dingqi weiquan xunhang zhidu guanli fanwei (China establishes rights defense patrol system for all waters, 3 million sq km of administrative waters brought into administrative scope of regular rights defense patrol system),” Zhongguo Haiyang Bao (China Ocean Daily), August 5, 2008 (http://www.oceanol.com/redian/kuaixun/2226.html). Such technologically advanced, white-hulled fleets have become central to the competition over maritime space in Asia, with China’s rivals rushing to upgrade their own coastguards, on-water law enforcement authorities, and maritime surveillance systems. These mobile outgrowths of the technosphere are redefining the terms of competition over the seas – away from access, and towards occupation and control. In this way, twenty-first-century maritime disputes have increasingly come to resemble terrestrial disputes over (sparsely populated) land areas.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Technology has also reconfigured the role of paramilitary law enforcement at sea. Far from maritime safety and fighting crime against specific targets like smugglers, maritime law enforcement is now increasingly geared towards the performance of sovereignty. The potential implications of China’s “Great White Fleet” in advancing its unilateral administration of disputed maritime spaces started to become clear to outside observers by the start of the 2010s.Ryan Martinson, "Here comes China's great white fleet," The National Interest, October 1, 2014 (http://nationalinterest.org/feature/here-comes-china%E2%80%99s-great-white-fleet-11383). The white-hulled strategy appears to have come to the attention of the US government in around 2010, judging by its debut appearance in the 2011 edition of the Pentagon’s Annual Report to Congress, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2011, p. 60 (https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2011_CMPR_Final.pdf). But their effect is even more profound when viewed from Beijing, where key policymakers operate – rightly or wrongly – on an assumption that principles of prescriptive acquisition apply to the sea, as they traditionally have done on land.On prescription in territorial acquisition, see Surya Prakesh Sharma, Territorial Acquisition, Disputes and International Law. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1997, pp. 108‒15; Brian Taylor Sumner, “Territorial disputes at the International Court of Justice,” Duke Law Journal, vol. 53 (April 2004), pp. 1787‒88. As China rolled out its regularized patrol system using the CMS force in 2008, its party boss Sun Shuxian asserted that there are just two principles regarding the existence of state authority in disputed waters: one is “effective administration” (有效管理), the other “actual control” (实际控制). Without these, Sun said, there was little point in claiming that the area was in question.Yu Wei, “Zhongguo Haijian youwang cheng haijun yubeiyi budui (CMS may become naval reserve force),” Nanfang Dushibao (Southern Metropolis Daily), October 20, 2008, AA16 (http://lt.cjdby.net/thread-542012-1-1.html).

From this perspective, the activities of all civil technologies – not only patrol boats, but also fishing trawlers, oil rigs, and even cellphone signals and weather reports – are not merely asserting the state’s presence, advancing the national economy, addressing its energy security, or carrying its communications. Rather, they are seen as performatively creating state sovereignty at sea.SOA, ZGHYNJ 2010, p. 127. The CMS East Sea Branch’s entry to the 2006 yearbook refers to a centrally approved guideline (中央批准的方针) of “display jurisdiction and embody China’s sovereign rights” in contested waters. SOA, ZGHYNJ 2006, p. 164. The previous year’s entry states, “The principles of ‘highlight presence, ensure safety, manifest our sovereign rights and administration of these waters’ were effectively implemented, and powerfully supported and complemented our government's diplomatic actions.” SOA, ZGHYNJ 2005, p. 193.

MANUFACTURING LAND, LEVERAGING THE HEAVENS

It is hard to imagine a more vivid illustration of the technosphere’s role in altering the boundaries between land and sea than China’s construction of artificial islands in the Spratly archipelago. Over the course of approximately eighteen months, using dozens of industrial dredgers and coral-cutting machines, the PLA turned seven tiny reef outposts into bases larger than any of the natural landmasses in the area. In all, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), they managed to transform nearly 1,300 hectares of the world’s most contested maritime space into new territories that now host small cities, with three airfields, dozens of buildings, roads, parks, leisure facilities and, based on recent satellite photography, silos ready to take surface-to-air missile deployments.“A look at China’s SAM shelters in the Spratlys,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, February 23, 2017 (https://amti.csis.org/chinas-sam-shelters-spratlys/). China was not the first country to reclaim land in the Spratlys. But the speed and scale of the sea-to-land conversion was unprecedented.Over the years, Vietnam is believed to have expanded its Spratly outposts by just under 50 hectares, Malaysia around 30 hectares, and the Philippines and Taiwan around 4‒6 hectares each. This, in turn, was a direct function of China’s economic, industrial, logistical and, above all, technological capabilities.See Andrew Erickson and Kevin Bond, “Dredging Under the Radar: China Expands South Sea Foothold,” The National Interest, August 26, 2015 (http://nationalinterest.org/feature/dredging-under-the-radar-china-expands-south-sea-foothold-13701?page=show).

China’s desire to “fill in the sea to manufacture land” (填海造地) on this industrial scale reflects its latecomer status in the Spratly Islands. The Spratlys are by far the largest of the South China Sea’s disputed archipelagos. Unlike the claims to maritime spaces discussed above, which are largely the product of the UNCLOS era, China’s claims to these island territories were inherited from the PRC’s vanquished civil war rival, the Republic of China, which fled to Taiwan in 1949. When a scramble to occupy the islands began in the late 1960s, Mao’s China was preoccupied with the Cultural Revolution, Soviet threats to the northern land border, and rapprochement with America. As a result, the few ships the PLA possessed remained thousands of kilometers away while the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia staked out all of the dozen or so genuine islands in the Spratly group.

By the time the PLA Navy finally made its move on the Spratlys in late 1987, all the prime real estate was occupied, and it took a fierce naval skirmish with Vietnam just to establish a tenuous foothold on six submerged reefs. Through the 1990s and 2000s, China consolidated its outposts from rickety huts on stilts, to slightly more solid-looking pillboxes, and then to a third generation of “reef forts,” before the island construction began in 2013.

These shallow patches of ocean – to the naked eye often virtually indistinguishable from the surrounding azure (as many shipwrecked navigators discovered) – concealed complex and spectacular underwater coral ecologies. Marine biologists believe the land-based military and civilian presence of all sides – particularly horizontal expansions of the technosphere like infrastructure development – has been adversely impacting the surrounding marine ecology beneath the waves for some time.Terry Hughes, Hui Huang, and Matthew Young, “The Wicked Problem of China’s Disappearing Coral Reefs,” Conservation Biology, vol. 27, no. 2 (2013), pp. 261‒69; Dune Lawrence and Wenxin Fan, “Islands of Mass Destruction,” Bloomberg, December 25, 2016 (http://thestandard.com.ph/opinion/columns/225000/islands-of-mass-destruction.html). But the recent island-building project is unique for having transformed entire marine ecosystems into sandy mid-ocean deserts.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Vertical extensions of the technosphere have also contributed to the blurring of the political status of land and sea.See Johan Gärdebo, “Technosphere Verticality,” Technosphere Magazine, November 2016 (http://www.technosphere-magazine.hkw.de/article1/e93d92c0-9eb3-11e6-87f4-45da4d91e2c2/5f112fd0-914d-11e6-bb8e-515155f3fd55). In the Spratlys, Vietnam and China operate rival cellphone networks; China’s reportedly sends automatic “Welcome to China!” text messages to every handset that comes within range.Lawrence and Fan, “Islands of Mass Destruction.” Once again, as with the 1958 continental shelf agreement, sovereign claims extend precisely as far as the technosphere will carry them. But the single most consequential example of the technosphere’s role in territorializing Asia’s maritime spaces occurred in the Scarborough Shoal incident of April 2012.

On the morning of April 10, 2012, the Philippines’ naval ship BRP Gregorio del Pilar arrived at Scarborough Shoal, an isolated atoll around 125 nautical miles off the northern coast of Luzon, to investigate a group of Chinese fishing boats spotted two days earlier by an aerial patrol. After the warship anchored outside the entrance to the sprawling lagoon, it dispatched armed soldiers on dinghies to investigate.Award in the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China, Permanent Court of Arbitration case no. 2013-19, July 12, 2016, 325 (http://www.pcacases.com/web/view/7). After collecting photographic evidence of large quantities of endangered giant clams and corals on board the Chinese fishing boats, the Philippine soldiers returned to the ship, apparently with the intention of detaining and processing the crews the following day. However, late in the afternoon, two CMS patrol boats arrived and took up positions between the Gregorio del Pilar and the fishing boats, physically preventing their arrest.For a blow-by-blow account from fisherman Chen Zebo (陳則波) see Zeng Ming, “Hainan yumin: qu Huangyan Dao yao zuolao (Going to Huangyan Island means going to jail),” Nanfang Zhoumo (Southern Weekend), May 4, 2012 (http://news.qq.com/a/20120504/000428.htm). Thus began a two-month standoff at sea that ended when the Philippines withdrew its ships ahead of a typhoon, leaving China in control of the disputed atoll.By August, Manila had issued twelve formal diplomatic protests over the incident. Ryan Chua, “Philippines to bring China dispute to world body,” ABS-CBN News, August 3, 2012 (http://news.abs-cbn.com/-depth/08/03/12/philippines-bring-china-dispute-world-body). Thereafter, Manila refrained from sending its ships back to Scarborough Shoal, while their Chinese counterparts maintained a constant presence. China emerged with effective control over the shoal.In late 2016, following new Philippines President Duterte’s strong pro-Beijing overtures, the PRC began tolerating Filipino fishing activities at the shoal. But it did not withdraw its ships from the shoal, making clear that Philippine fishing took place at Beijing’s pleasure. “Pinoy fishermen say they can fish in Scarborough Shoal again,” ABS-CBN News, October 28, 2016 (http://news.abs-cbn.com/video/news/10/27/16/pinoy-fishermen-say-they-can-fish-in-scarborough-shoal-again).

The Scarborough Shoal incident was a smokeless battle for territorial-style control of maritime space, fought across the technosphere’s horizontal and vertical dimensions. The trigger for the confrontation was the Philippine military’s decision to dispatch its largest naval vessel to investigate the Chinese fishing activities first spotted by an airborne patrol on April 8. This response, in turn, was made possible by the US’s provision of the vessel, a refurbished coastguard cutter, which had been commissioned into the Philippines Navy in December 2011. The next key link in the causal chain was the emergency distress call system that had recently been installed on the PRC fishing boats. This enabled the crews to instantaneously alert authorities in Hainan of the situation using the Beidou satellite navigation system, which with near-perfect synchronicity had entered service the same month as Manila’s flagship whose mission it would thwart.Geoff Wade, “Beidou: China’s new satellite navigation system,” Flagpost, February 26, 2015 (http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2015/February/Beidou_China_new_satellite_navigation_system). Finally, the ability of the two CMS ships to reach the area in time to prevent the arrests was a direct result of their being in the area on a “regular rights defense patrol” at the time – a program enabled by technologies whose genesis lay, as detailed above, in the legal instruments China crafted in response to the arrival of the UNCLOS regime under which half the world’s maritime littoral was territorialized.“Liu Cigui: Bohai yiyou haishang wuran yanzhong, haiyang fazhan luobi shengtai baohu (Liu Cigui: pollution serious from Bohai oil spill, signing up to ecological protection),” Phoenix TV, June 11, 2012 (http://phtv.ifeng.com/program/wdsz/detail_2012_06/11/15202134_0.shtml).

CONCLUSION

This dossier entry has detailed how the scope of land-based state authority over East Asia’s seas has been intimately related to the horizontal outgrowth of the technosphere. The development of offshore oil and gas was integral to the original seaward thrust of state authority in 1945, and in 1958 international law left the extent of that authority in the impersonal hands of technological development. Yet, this alignment between technosphere and land-based dominion over the sea was by no means a new development. The historical ascendancy of the “free seas” doctrine was dependent on sponsorship from a succession of technologically advanced maritime hegemons. And even during this period, exclusive state authority over the seas was widely accepted out to a distance of 3 nautical miles from the coast – a figure derived from the putative range of a cannon shot.

Nor is there anything novel (or indeed technologically determined) about changes in the land‒sea divide in Asia. Like the volcanic eruptions that in 2013 created the new island of Nishinoshima (which Japan may use to expand its own EEZ claim), or the storms that apparently created a new territory at Luconia Shoals in the far southern reaches of the Spratly Islands, the edges of land and sea are naturally always shifting.See Andrew Chubb, “Luconia Breakers: China’s new ‘southernmost territory’ in the South China Sea?” South Sea Conversations (blog), June 16, 2015 (https://southseaconversations.wordpress.com/2015/06/16/luconia-breakers-chinas-new-southernmost-territory-in-the-south-china-sea/). What is novel is the role of the outward, upward, seaward spread of human tools in precipitating so many recent changes – and the layers of meaning that such changes accrue in the context of our categorical knowledge schemes, of which the land‒sea dichotomy stands as one of the most fundamentally inescapable.