Boris Solovyev

Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island, Lena Delta resource reserve

The Lena Is Worthy of Baikal: Defining Remoteness Across the North and the East

What is remoteness? What kinds of narratives drive its representation, creating a violent topology of the distant and disconnected? Inspired by her experience of travelling to an abandoned “non-place” during a research trip to the Lena River Delta in northern Siberia, historian of science and technology Ksenia Tatarchenko reflects on filmic dramatizations of far-off and inaccessible places, capturing the fleeting role Soviet modernity had in establishing interconnection in isolation.

Remoteness is a relative concept. Distance is its first and most obvious association—distance between locations and people. It is also a characteristic that the North and the East share when viewed from Europe—they are faraway places. Getting there is a journey, remoteness being as much an obstacle as it is an attraction, an elsewhere that we long for. There aren’t many places in the North and in the East that fit this notion better than Tiksi, one of the main ports of the Russian Arctic, situated near the delta of the Lena River on the shore of the Laptev Sea. Flying is the main means of traveling to the town, which was created as part of the infrastructure for the Soviet Northern Sea Route in the 1930s. My own experience of traveling to Tiksi supports the widely acknowledged fact that while technologies can shrink distances, they also partake in recreating sites of remoteness. To get a few Swiss students studying climate change on a Tiksi-bound plane is to experience remoteness as aloof and unfriendly. Crossing the Russian Border Security Zone involves additional paperwork, scientific instruments require special permissions, and even booking plane tickets is a challenge, as the banks block the online transactions of small Russian aviation companies. In the summer of 2017, I spent one month at the research station on the island of Samoylov in the Lena River Delta (72°22’ N, 126°29’ E), some 100 kilometers west of Tiksi, heading the group of students from the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne who took part in the international research expedition.For a description of the station by its operator, Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum-Gas Geology and Geophysics, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, see http://samoylov-island.ru/en. My experience of remoteness in the two senses mentioned above, as obstacle and attraction, provides a stepping stone to reflect on two other aspects of the concept:

remoteness as a “probability” and as a process of breaking connections.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

small

align-left

align-right

delete

I am convinced that considering these different aspects of remoteness is helpful for conceptualizing a distinct Soviet version of modernity. Neither the task of grasping Russia’s Arctic ambitions today nor a truly global environmental history can do away with the Soviet legacy in these regions. The reasons are many. The geographical arguments based on the sheer size of the Russian Arctic and the genealogical connections between past and present Arctic infrastructures, such as the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) and the Northern Sea Route, are certainly crucial, but they are out of the scope of this essay.For an overview, see Peter Schweitzer, Olga Povoroznyuk, and Sigrid Schiesser, “Beyond Wilderness: Towards an Anthropology of Infrastructure and the Built Environment in the Russian North,” Polar Journal 7, no. 1 (2017): 58–85. A less obvious but no less powerful argument goes beyond regional logic and rests instead on the very questions that we ask today about the politics of human-nature relations. The Soviet past takes on a new significance when reconsidered in dialogue with recent polar scholarship that argues against Arctic and Antarctic exceptionalism under the banners of the “post-polar” and the “New Arctic.”Ronald E. Doel, Urban Wråkberg, and Suzanne Zeller, “Science, Environment, and the New Arctic,” Journal of Historical Geography, no. 44 (2014): 2–14.

The two films that I focus on below, By the Lake (1969) and Sannikov Land (1973), are particularly remarkable for how they dramatize remoteness in a way that diverges both from today’s media construction of the North as a wilderness and from the received narratives of Soviet environmental history as that of an irrational abuse by the state. These representations disturb communist obsessions with the conquest of nature and the Stalinist system of forced labor to raise the question of what it means to establish a non-capitalist relationship between human and nature by offering their own version of the remote North and the East as homelands, frontiers, and non-places. The politicization of the Soviet depictions of these regions is no longer to be dismissed as propaganda but rather interrogated as historical resources on environmental politics. Deborah R. Coen, “Big Is a Thing of the Past: Climate Change and Methodology in the History of Ideas,” Journal of the History of Ideas 77, no. 2 (2016): 305–21.

* * *

Lake Baikal is the most obvious site for peering into the checkered relationships between the technological, epistemic, and natural orders of late Soviet remoteness. Among Lake Baikal’s many superlatives—the deepest, cleanest, and oldest lake in the world—is also a historiographic one. The public campaign to prevent the construction of two pulp plants near the lake, which took place in the late 1950s and early 1960s, is the best-known episode of Soviet environmental history.For further references, see Douglas R. Weiner, A Little Corner of Freedom: Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), especially chapter 16, “Storm over Baikal.” The terms and chronology of the debate deserve a supplementary reflection.

Arguing against the construction of the plants, the Siberian geologist Gennadii Pospelov depicted Baikal as a natural laboratory, key for accomplishing the long-term and global political project of communism:

We are a society actively creating the future of humanity, and for that reason we must place on the scales of benefit and harm to the state the interests of our descendants as well.G. L. Pospelov, “Razmyshleniia o sud’be Baikala,” quoted in Weiner, A Little Corner of Freedom, 362.

The campaign failed. Less famously, the defenders of the construction sites of the pulp plants, which were relying on Lake Baikal’s pure, silicon-free water included several defense ministries responsible for developing novel, super-light, and resilient materials that incorporated the organic products of the pulp plants as part of the Cold War technological race. A legal compromise came about when the state kept issuing decrees setting out measures for preserving the lake and the plants kept on polluting. Of limited practical efficiency, the legal framework nonetheless justified broadening the terms of the conversation into a debate about the promises and failures of a socialist modernity. In fact, taking the failure of the campaigns as an endpoint and the opening of the plants as an illustration of the absurdity of the centralized planned economy recognized by Soviet intellectuals and the public is as straightforward as it is misleading. For Soviet contemporaries, the “Baikal problem”— the way it is typically referred to in Russian—was never resolved. Discussing the fate of the two plants and the industrial communities that grew around them but also for an ongoing reflection on the values animating the socialist project. Rather, the lake became a site not only for discussing the fate of the two plants and the industrial communities that grew around them but also for an ongoing reflection on the values animating the socialist project.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In the 1969 movie By the Lake, the notorious Soviet director Sergei Gerasimov depicts science and technology as belonging to a larger set of relationships: the Baikal landscape and library, laboratory, and shop floors are represented as interconnected spaces.Sergei Gerasimov, director, By the Lake (Soviet Union: Kinostudiya imeni M. Gorkogo, 1969). The film is available on YouTube at https://youtu.be/TB8zaRRrhHo. Expertise appears on both sides of the Baikal debate as an argument for conservation and the power to propose a solution. One of the most popular titles of 1970, the feature film won mainstream and critical acclaim by presenting the issue not as a battle of technology against nature but as a perennial drama of human choices. Baikal is represented not as a charismatic natural object and symbol of the future of humanity—the emphasis of many expert and popular accounts of the 1960s—but as a habitat paced by genealogical and seasonal times and already, not potentially, belonging to humanity’s cultural patrimony.

The movie, shot on site in the town of Baikalsk, was part of the director’s trilogy devoted to identifying “heroes” of the 1960s, a motivation that explains the film’s merging of feature and documentary aspects. The images of the main building of the plant constantly reoccur in the film, as the message of the letters decorating its facade, which spell out the slogan “Communism is our goal,” is questioned and debated. The tension between the two key protagonists—Lena Barmina, the daughter of the biologist arguing for preserving the lake, and Vasilii Chernykh, the director of the factory under construction—is amplified at the intersection of the personal and the political. The lake is a site where their conflicting visions of communism—beauty versus work—are confronted and where their adulterous love affair burgeons.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The resolution of this conflict is impossible: the film ends with Chernykh tormented by the need to increase the factory’s production, and consequently, its pollution, as well as the impossibility of finding individual happiness; Barmina escapes from the impossible infatuation and leaves her home and Baikal behind. The message of the film is neither linear nor negative, however. Improbable and impossible, the union of the protagonists is consummated as a commitment to patriotic feelings. The scene featuring their exchange of lines from the Silver Age poet Aleksandr Blok at a public poetry reading is one of strongest in the film.Bromina reads Blok’s “The Skyphians” (1918), and Chernykh answers with lines from “On the Field of Kulikovo” (1908).

In their devotion to the motherland, social conventions and temporary conflicts make room for eternal values.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

The factory director—incarnated by the Altai-born actor, director, and writer Vasilii Shukshin—comes across as a living Skyph, and the young woman as the Rus of Blok’s poetry. The tension of the public reading scene engulfs the film’s audience and simultaneously rehearses a possible role of the Soviet public sphere as a space where individuals are to make sense of the meaning of communism as a global and a personal project.

“Placeness” is central to the film’s unresolved dialectics in aspects ranging from its title to its composition. Opening with shots through the windowpane of a moving train, the film ends with the main protagonist leaving her home and watching Baikal from the bus. Her destination is in the North: Lena goes to the Lena. According to one of the movie’s scenes, “the Lena is worthy of Baikal”; it is not just a river, but a sea that flows. That the two sites are designated as “homelands” is not accidental but a fulfillment of the film’s key statement, stipulating that “one cannot spend all her life by the lake.” Remarkable here is not only how the interconnecting of two remote locations as a trajectory of personal growth subverted the discourse of Baikal exceptionalism that dominated earlier environmental conversations. The obvious implication and argument of the film was that the debate about humankind’s place in nature is not bound to Baikal, or the Arctic, for that matter. At the same time, while making clear the destination of the protagonist, Gerasimov leaves the audience with a greater uncertainty. The future of both the human and the natural, Lena and the Lena, appear disquieting and open-ended.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

* * *

The concluding scenes of Gerasimov’s movie are about the remote prospects of human-generated climate change in the North, and specifically the northeast, through the construction of a dam across the Bering Strait. Despite the film’s emphasis on uncertain outcomes, the subject of the final lines of dialogue is neither fictional nor fantastical. It echoes the projects being discussed in the press at the time that suggested various geoengineering options to render the Soviet Arctic more hospitable. Such were the aspirations of P. M. Borisov, who calculated how lowering the level of the Chukchi Sea would bring the warm waters of the Gulf Stream farther along the coasts of the Soviet Arctic.See I. I. Adabashev, Chelovek ispravliaet planetu (Moscow: Molodaia Gvardiia, 1959,); and P. M. Borisov, Mozhet li chelovek izmenit’ klimat (Moscow: Nauka, 1970). [Can Man Change the Climate?] A dam powered by atomic energy would regulate the flow of water and serve as a transport link between Europe and North America. Remoteness as uncertain probability gave license to imagination, and futuristic bridge-cities proliferated in the illustrations of popular science magazines such as Tekhnika Molodezhi.K. Lucheskoi, “Gorod-plotina,” Tekhnika-Molodezhi, no. 1 (1974): 20–21. [ “Dam City”, Technology for the Youth] The underlying geopolitical assumption for the magazine’s futuristic projection situating the city in the year 2000 was obvious to all Soviet viewers—the year of the global triumph of labor and creativity over capital. This late Soviet version of the post-polar as post-capitalist does not sit easily with us. Yet the overlap between the semantic domains of the remoteness and utopian imaginaries points to the utopia’s dystopian double: the apocalyptic narrative model we are most accustomed to. And in fact, Soviet popular culture did not fail to supply a particularly vivid example, where an Arctic catastrophe actually became the setting for substituting assumptions of global communism with a quest for interpersonal loyalty.

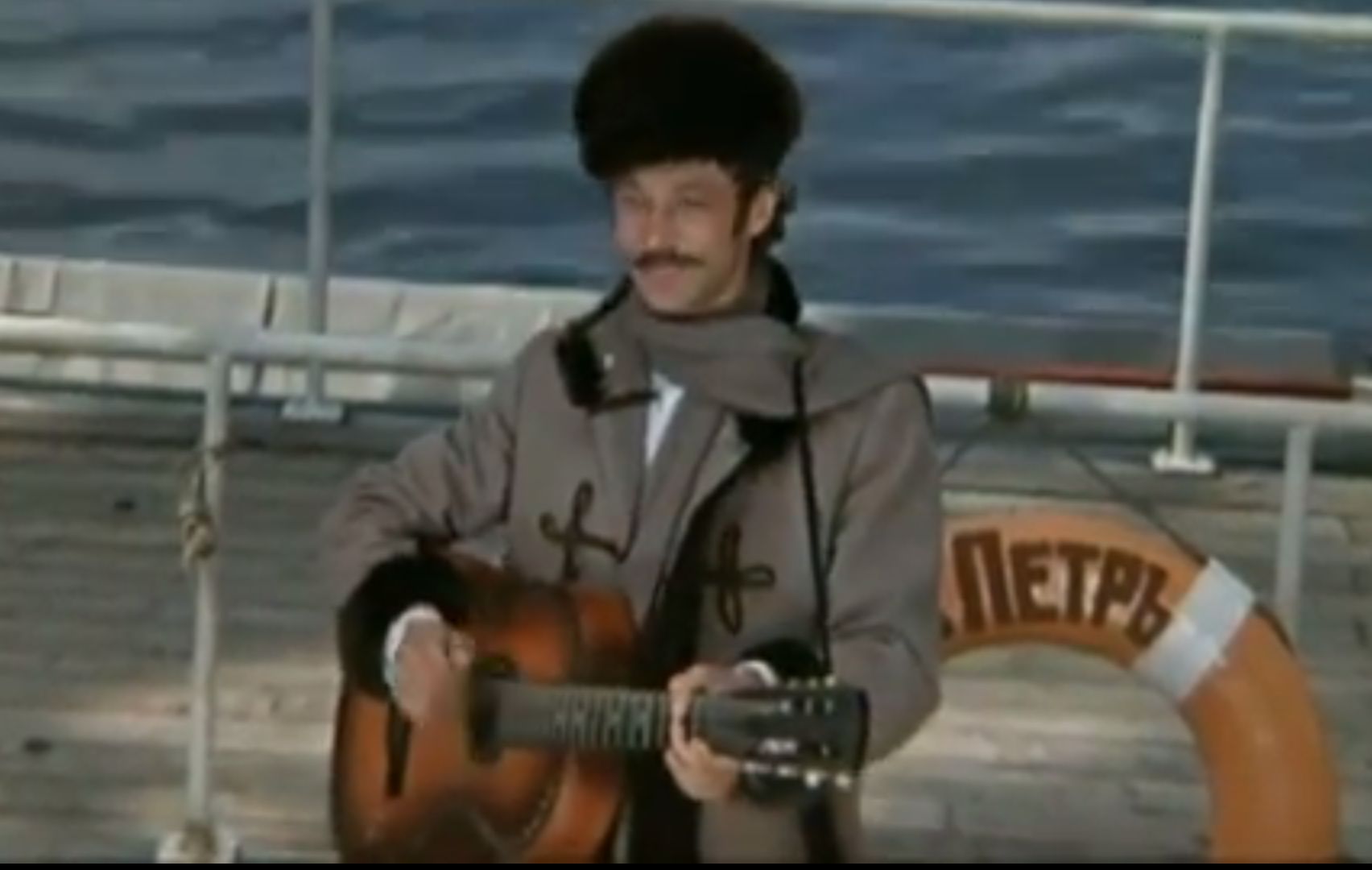

Placelessness characterizes the most popular representation of the Arctic in the same period. Loosely based on the fantastic novel of the Soviet paleontologist Vladimir Obruchev, the 1973 silver screen version of Sannikov Land, directed by Albert Mkrtchyan and Leonid Popov, did not win its status in pop culture memory for its abortive plot line but rather for its remarkable cast and soundtrack.Albert Mkrtchyan and Leonid Popov, directors, Sannikov Land (Soviet Union: Mosilm, 1973). The film is available on YouTube at https://youtu.be/pYENPwgfJqE. The film amounts to the adventures of a group of explorers searching for Sannikov Land, the phantom island allegedly seen in the Laptev Sea. The group finds the island, only to contribute to a natural cataclysm that destroys the land and with it the inhabitants, the Indigenous people of the Onkilons. The half-century gap between the 1926 novel and the 1973 film is the main explanation for the subversion of the novel’s key messages, both educational and inspirational, for the conventions of the adventure genre. In the 1920s, phantom lands still appeared on maps, as sea access to the area north of the New Siberian Islands was notoriously difficult. Obruchev concluded his novel with a call for further research; the real-life mystery was finally resolved in the 1930s with the development of polar aviation.V. A. Obruchev, Zemlia Sannikova ili Poslednie onkilony: Nauhno-fantastiheskii roman (Moscow: Puchina, 1926). [Sannikov Land, or the Last Onkilons] The 1973 film presented itself as entertainment. Unlike Gerasimov’s aesthetics of purity codified in black and white, Sannikov Land is rife with B-movie visuals.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The film not only cuts across the novel’s plot and purpose, but it also subverts the main temporal axes of the novel. For Obruchev, the mystery of Sannikov Land made it possible to combine spatial and chronological remoteness, where overlapping temporalities offered a reflection on natural evolution paired with a discussion on succeeding social orders. In striking opposition, the 1973 film version forewent both spatiality and temporality: the film operationalizes remoteness to subvert the expected connections. Instead of Hegelian progression, it glorifies the most human-centered category of here-and-now—the fleeting instant. The film’s theme song became one of the greatest hits of the late Soviet era. The song is integrated into the plot, appearing to belong to and thereby define one of the key protagonists, the daredevil officer and bard Evgeniy Krestovskiy. This role was initially written for Vladimir Vysotsky, the iconic Soviet poet, singer, and actor of the 1970s. Even though a different actor eventually played the role, the iconography of Krestovskiy’s self-sacrifice in the extreme Arctic conditions is a reference to Vysotsky’s “Song of a Friend.” The human scale of the film, signaled by the instantaneous, does not deny all responsibility of the individual but rather emphasizes individual choice: the poet perishes to save his friend. Krestovskiy’s refrain, “there is only an instance, between the past and the present, there is but a single instance, and this instance is called life,” became disassociated from its Arctic context as it acquired the status of a generational statement.For recollections of the song and the film, see Svetlana Samodelova, “Tainye kadry sovetskogo Avatara,” Moskovskii Komsomolets, September 8 2011. [The Secret Frames of the Soviet Avatar]

Although the film is devoid of the ethical and aesthetic ambitions of Gerasimov’s By the Lake, the light adventure genre in which Sannikov Land peddles does not prevent it from depicting its own version of scientific expertise in a clearly declinist mode. The protagonist, driven by the search for knowledge about the mysterious land, performs the characteristic activities of field work and can grasp Sannikov Land’s geological secrets. While he is the only one to return from the expedition, he is nonetheless unable to prevent the environmental cataclysm that finally destroys the land. The explorer is saved by Indigenous people, who have the last word in the film, asking:

Man, why are you marching on the Earth?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

* * *

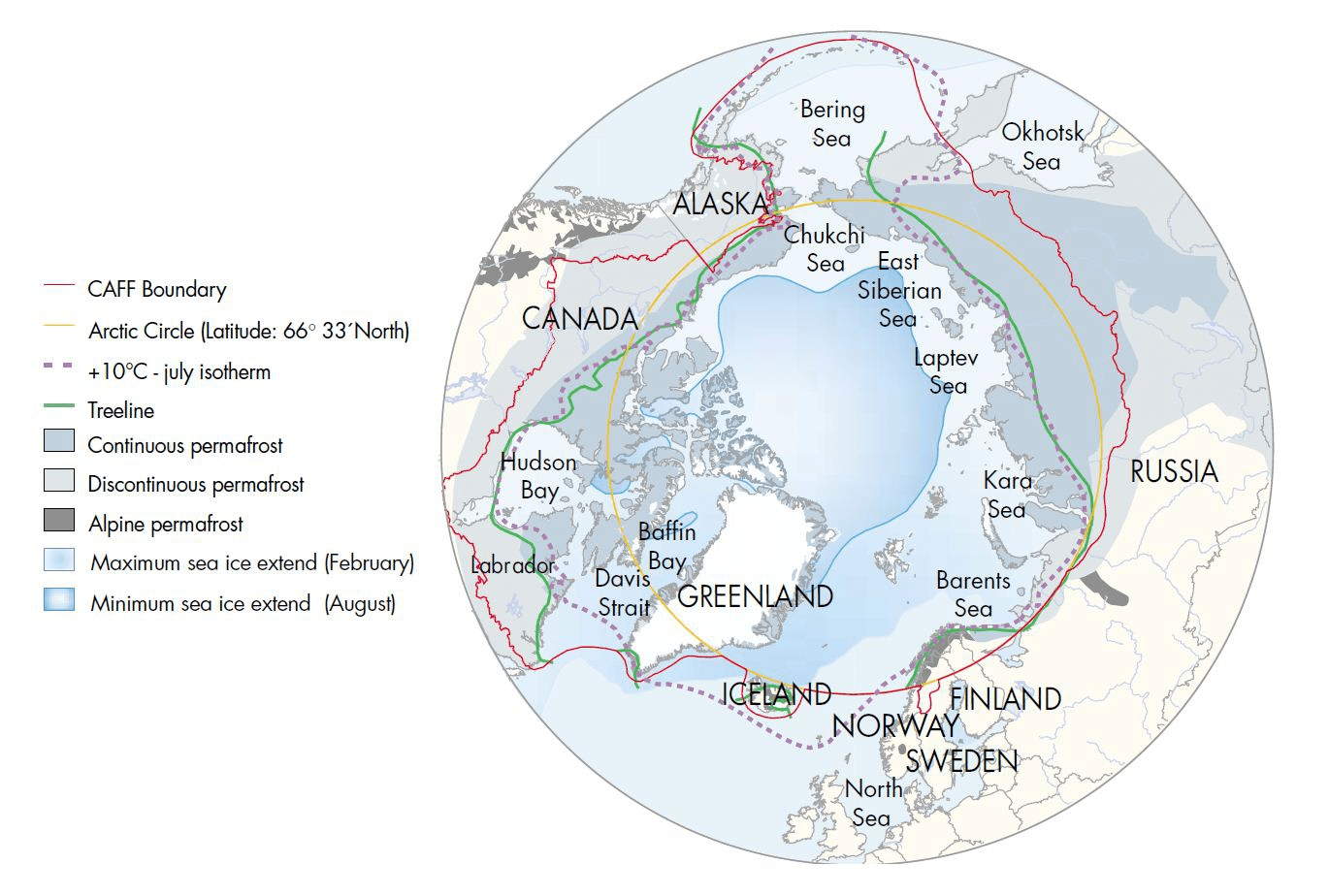

Seen from today’s perspective, Sannikov Land’s hot and disintegrating Arctic is simultaneously familiar and exotic. The warming Arctic is what brings scientists to go out into the field in many remote locations. Melting permafrost is one of the major problems, both scientific and technical, as statistics show the increasing fragility of infrastructures built upon the frozen earth that spans almost half of the Russian territories. Moreover, it is a problem our climate models are poorly equipped to deal with. Firsthand experience shows there is little permanent about the permafrost that forms some two thousand islands of the Lena River Delta; the coastline threatens to collapse under one’s feet and eventually melt and drift away on the current. And one frozen earth is not equal to another: yedoma, the Pleistocene-age permafrost known for its high content of organic matter, has a distinct smell and leaves a somewhat sticky feeling on one’s fingers. Permafrost is not an exceptionally mutable Arctic entity, however. The Arctic itself offers little stability and changes its definitions where it is no longer circumscribed by the Arctic circle: for instance, the permafrost frontier stretches all the way along the Lena and southward beyond Baikal. As permafrost’s active layer freezes and unfreezes, new expeditions ready themselves to return to the field.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

To a science and technology studies scholar, the isolated communities of researchers at the stations are reminiscent of tribes—summoning up a scholarship in which networks of scientists have repeatedly been likened to or studied as moneyless societies, wherein people are differentiated by experience and authority and where acceptance is a matter of rituals. This is also where the train of associations breaks apart. The time spent at a station is a time of active construction of new sets of relations, which is particularly intensive because these relations are temporary and oriented at maximizing the gathering of samples and data. As scientists come and go from a station, the staff remains, servicing its vital equipment, such as the diesel reactor that keeps it running through its yearlong operation. A permafrost observatory to scientists, it is a home to technicians. While chitchatting at the Samoylov station, I learned that one technician moved to Tiksi for job opportunities in the late 1970s. “Those were good times,” he likes to reminiscence. “Back in those days, we had all our things ‘made in Japan." One of the powers of remoteness is that it exposes improbable connections.

When Bruno Latour came back from the Amazon rainforest, he recreated his observations as a powerful analytical argument in the form of photo-philosophical montage, playfully subverting the conventions of epistemology and the history of art.Bruno Latour, “Circulating Reference: Sampling the Soil in the Amazon Forest,” in Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 24–79. Neither rehearsing nor challenging the constructivist agenda, this essay is an illustration of the mechanisms of remoteness that are left out of Latour’s “Circulating Reference” essay. One is the transformation of the observer’s affect through a spatial reversal, a condition where home or the point of provenance becomes a marker of distance. The second point is connected to the first: attachment to a place comes with learning stories and making sense of the local history. For me, it became hard to separate the personal and professional in my experience of remoteness, which is the reason I turned to not an analytical but a methodological argument here.

Predicting the sensitivity of permafrost to a warming climate is the purpose of the Samoylov station, and thanks to science studies we are well equipped to understand this agenda and analyze the research activities. However, getting to Tiksi is a shock that no historiography can prepare one for. To land in Tiksi is to confront the end of Soviet history laid bare. The averted apocalypse of the Soviet collapse is a hypocrisy; Tiksi’s remoteness is a monument to the violence of abandonment. My turn to representation in this essay is a deliberate response to this shock. I put forward a case that today’s conversation can be opened up to include a larger sequence of mediators in order to recapture our changing relations with nature. Rethinking the modernization project is predicated on acknowledging its inheritance. If both “remoteness” and “modernity” are notoriously vague terms, then instances of their dramatization such as those discussed above matter even more. In any case, it is certain that neither the “post-polar” nor the “post-Soviet” category will have full analytical power without first making sense of Soviet presence in the Arctic, Antarctic, and Siberian regions and its public articulations.

large

align-left

align-right

delete