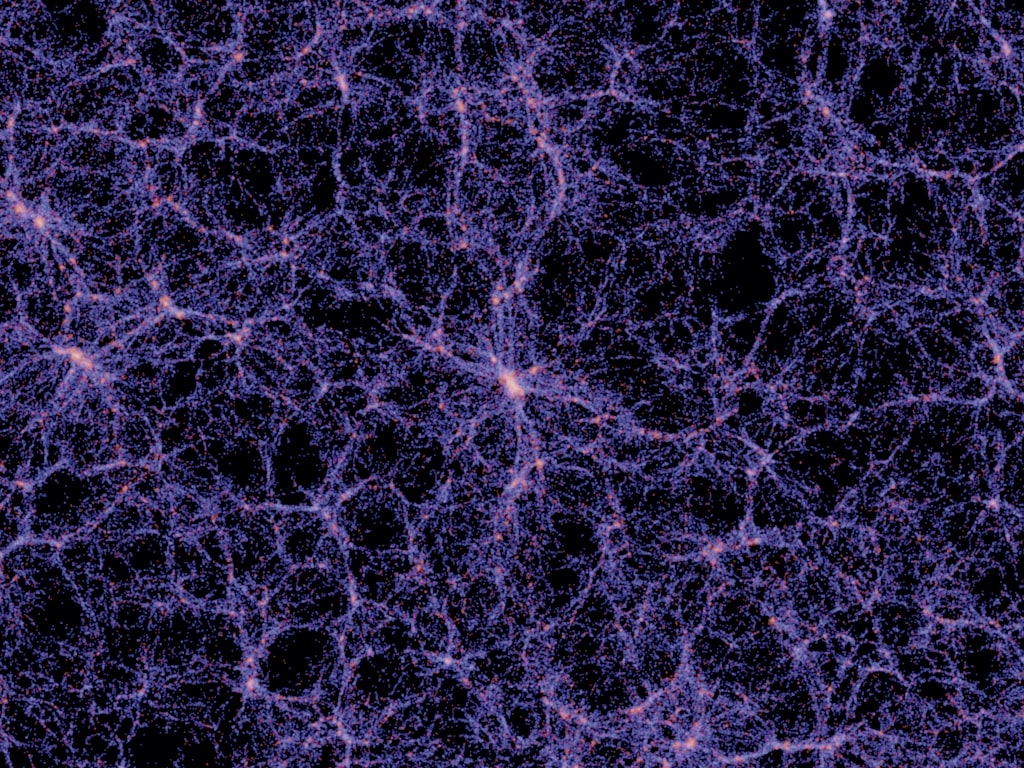

Volker Springel, MPA Garching 2005

Simulation of the formation of galaxies

Embedded

In their long-standing conversation, artist François Bucher and primate researcher Lars Kulik seek to find grounds upon which to conceptualize the ever-evolving web of life as a cooperative and mutually resonant supraorganism. For them, it is up to humans to become active in raising the frequency of the Earth, cell by cell, in order to take part in a conscious universe. And it is up to science to tune in to this resonant cosmic community.

This text is a kind of channeling of a conversation that has been running for about a decade. Our procedure was the following: in view of writing this article, we first had several dialogues where we tried to re-channel some of our recurring themes. We focused on some questions that were naturally coming to the fore, we shed some of the directions of thought that seemed to have expired, and then we roughly chose what we would focus on. We then engaged in a written exchange composed out of a text that we each wrote, to which the other added a sort of response or follow up.

François Bucher: The short version of what brings us together in this dialogue is that we are invested in visions that undo a materialistic, mechanistic world view, and that we see a crucial initiation path for the human in this passage. I am feeling the need to be incredibly diagrammatic in this conversation so, in the same vein, I would like to bring in the notion of an immaterial science as a counterpart to those two words. It is a cliché distinction, which has been used by too many, but it has the virtue of undoing other more crass oppositions – between science and art, or between science and religion to name two.

I want to bring in a novel that has given me a workable parable. The novel is called Contact, written by Carl Sagan, published in 1985. As far as I am concerned, it is pinpointed in addressing the complexity of the communication between worlds that run on different laws. As you will see, there are at least two different meanings in that phrase. Carl Sagan imagines a situation to illustrate this case, which I will try to describe. He is informed by a vast knowledge of astrophysics and is therefore very apt to stage such a complexity. The heroine of this novel, Ellie, is involved with SETI ‒ the “search for extraterrestrial intelligence” ‒ Sagan’s life passion. In the story, “contact with the ‘absolute other’” is established and the world goes into turmoil. After many detours, Ellie ends up being chosen to represent the human race. Ellie is a scientist and as such, she gears up to record her Encounter for further analysis. The machine is ignited ‒ one costing half a trillion dollars ‒ that originated in the blueprint sent from outer space, and Ellie is off on her mission. She travels through time‒space in a network of wormholes. When she reaches her final destination, she is struck by its beauty. Facing a celestial event, she pronounces the words “they should have sent a poet.” From here, she is transported to a fairy-tale beach. She soon realizes that the hallucinated landscape is inspired by an intimate fantasy of the little girl she once was. In the distance, she sees a blurry energy materializing into a man, who walks towards her along the beach. It is her father, who had died when she was a little girl. Her scientific mind is sharp enough to ask the right question: “you are not my father; you have materialized as such in front of my eyes ... why do you take your shape from my psyche?” The extraterrestrial intelligence asks her, in his turn, whether she could imagine a meeting that was not based on what she already knows. She understands. Among other questions, she asks why it was necessary for her to be alone in this encounter. He responds that there is no other way and that it has always been done like this, for millions of years. Back on Earth, she learns that the eighteen hours she had spent traveling had not taken place. From the perspective of the machine operators, something failed, and Ellie has just been on a free fall for half a second. The video material she had acquired during her interstellar trip was nothing but static. This by the way is a nod, on the part of Sagan, to the evolution he foresaw with the advent of radio telescopes. They would be listening to Cosmic Background Noise as a means to trace distinctions between wavelengths, in order to concoct diffuse color-coded images of time, of the origin of the Universe … yet “there are more things.” Ellie goes on trial, facing a senate committee that is bent on invalidating her claims of having established “contact.”

Ellie: Is it possible that it didn’t happen? Yes. As a scientist, I must concede that, I must volunteer that.

- Interviewer: Wait a minute, let me get this straight. You admit that you have absolutely no physical evidence to back up your story.

Yes.

- You admit that you very well may have hallucinated this whole thing.

Yes.

- You admit that if you were in our position, you would respond with exactly the same degree of incredulity and skepticism!

Yes!

- Then why don’t you simply withdraw your testimony, and concede that this ‘journey to the center of the galaxy,’ in fact, never took place!

Because I can’t. I ... had an experience ... I can’t prove it, I can’t even explain it, but everything that I know as a human being, everything that I am tells me that it was real!Quoted from the movie "Contact" (1997) by Robert Zemeckis.

Sagan corners the reader (and later the viewer of the film that goes by the same name) where they can no longer escape a certain question. One that our civilization has become increasingly sophisticated in avoiding. The contingent operating system that we call “reality” may have an utter breakdown, just like a laptop struck by lightning. Its magnetic poles can be reversed in one single blow, linear time may be shattered in one stroke, and with it everything about what “human” means. One can only be in the position of the realist until forced out of a self-fulfilling system, forced out onto THE OPEN. The basic tenets that we have not upgraded for a very long time may suddenly shift. Intellectually we were struck by lightning at the time of the quantum revolution, and Max Planck came up with some downright poetic phrases to describe the new horizon that was now facing humanity. Here is Max Planck, like Ellie, concluding that he is surpassed by beauty:

I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.Max Planck cited as in Shyam Wuppuluri and Giancarlo Ghirardi (eds), Space, Time and the Limits of Human Understanding. Cham: Springer, 2017.

And

As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clearheaded science, to the study of matter, I can tell you as a result of my research about the atoms this much: There is no matter as such! All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particles of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent Mind. This Mind is the matrix of all matter.Max Planck as cited in Clifford Pickover, Archimedes to Hawking: Laws of Science and the Great Minds Behind Them. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 417.

Planck would feature in the unwritten novel “A Portrait of the (real) Scientist as a Young Man”: and would be quite shocked at how conservative some directions of thought have veered within the Max Planck institutes. The fact that quantum, and the “double nature of reality” became synonymous with a race to make better computers, and not a QUESTION about who we are in the Universe, may be the perfect parable of the strange self-fulfilling bad trip in which we find ourselves. It expresses the nature of our disconnection: we are obsessed with technology, creating in turn a self-obsessed, autistic sphere that we have come to name the “technosphere.” A mechanical view of the Universe is based on fear, an institutional view of spiritual experience is based on fear; this is a very simple story of trauma and atrophy.

Lars Kulik: It seems to be the well-known fear of the stranger. The familiar gives us security while the unknown makes us afraid. To isolate oneself from the unknown seems to be the simplest solution. Unfortunately, anxiety and isolation are complementary to a negative spiral. In this fear-spiral, control, power, and the unconditional will for the sovereignty of opinion can become the prior motivation for action. The first advocates of science were exposed to exactly this spiral, and the representatives of the traditional at that time were relentless. Paradoxically, today it seems that science is the source of a similar fight.

From our history, it seems, any dogmatism is a dead end. The intrinsic will to stick with the traditional is too strong in a dogma. Dogmas narrow views; occasionally they lead to complete blindness, and they restrict the possibilities of thought and prevent development, and thus impede essential adaptations to new challenges.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

There is already a huge body of knowledge existing, which has already opened the door to a much wider awareness of what constitutes a human being, and “what holds the world together in its inmost folds.” But these are only pieces and for a lot of us those have no meaning. Due to our acquired perceptual filter, those are mostly not accepted. We learn many complicated things at school and at university, but most of this is external objectified knowledge. This is neglecting how we perceive the world.

François Bucher: In my professional field I fall onto a thousand traps for being inclined to pay heed to experiments in biology, in so-called psychic research or in hyper-dimensional physics, or crystallography, since the tacit dogma of the world of “discourse” is to instinctively reject any idea of the “laboratory” as reductionist; and any idea related to “being” as essentialist. Speaking about “alternate dimensions” of the human experience (or of plants and animals) falls within the metaphysical trap, which has so many false doors that the polemics around it are endless. In your field at the Max Planck Institute, on the contrary, the results of experiments that negotiate psychic phenomena, alternative energies, or paradoxical times are invalidated by the fact of them being not concrete enough, not being easily reproducible; not being “rock-solid science.” Between these two extreme dogmas lies a liminal space of experience-driven thought (not a cosmovision but a cosmoexperience) that is relegated as pseudoscience, male fantasy, or esoteric reverie. It is self-explanatory as to why this field is a minefield, because essentially it is a portal between worlds: the realist cannot see, smell, hear, nor touch this other world, therefore it is denied. Yet multiple quantum-style experiments in the psychic field show how the presence of a true stainless-steel skeptic can turn off the goings on of a séance, for example. So all these polemics are blurry. The field we speak about brings into contact two realities that don’t match; it opens up a hall of mirrors ... on both sides, on the side of philosophy and on the side of science based on hard facts.

As much as you make the most radical, creative timelines for the Anthropocene, finding its genesis in the “great oxygenation” or atomic bomb; or in the use of the thumb by our distant ancestors, or at the beginning of the Renaissance, if you are limited to a certain “organ of time” there is no chance that you can really start touching on the breadth of the human experience; because you are half-thinking.

There are many ways to describe the two hemispheres which form the vortex of a “whole” human experience. And they entail two different experiences of time. In the state we are in currently our thought has not even started, because there is atrophy. Let’s point out here, as a base paradigm, that it is known the Mayans were very advanced astronomers, meaning that they could predict an eclipse in the very distant future. But a more important point is they did not predict it out of a whim; they predicted the eclipse out of the need to make another kind of time map, non-linear, pattern oriented: the map that astrology is based upon. This other science ‒ immaterial by nature ‒ discovers patterns (you may call them archetypes, or Olympian deity) and it will suggest how that eclipse affects a person born on a certain date differently. To prove that the precept is right you would need a second Universe, which is why astrology is a virus that attacks the rock-solid science laboratory mindset, and is therefore shunned. On the other side of the looking glass, on the side of the “discursive,” the very existence of this science attacks the relativizing mind set, because the “body” is reintroduced to a head that thought it had outsmarted it. Not a mechanical body, but rather a supra-metabolism; a holographic body, a hyper-biological, non-local body; not detached, not safely dressed in a white vest with a stethoscope in its pocket; a body with an active correspondence with the stars. What I may be able to think today, in this moment, for example, as I speak these words, might be related to Saturn. Sequential time has laws, and we exist in the sequence, from that perspective. The sequential profile of the flipping coin is obviously easier to grasp by an incarnated body, which witnesses its decay, and perceives the approach of death “in the future.” But the full experience of time cannot be accounted for by the left hemisphere alone; it will be in need of the vortex to start generating real thought about both the Human and the Universe. The part and the whole are spinning in the vortex, and they cannot be made out, just like the particle and the wave cannot be made out in the experiment voted as “most elegant” in recent history ... about a reality that collapses into one of its possibilities in the act of observation. It is one thing to know this intellectually, yet another to learn it “by heart.” This is where a colossal consciousness-mutation happens, not when the experiment is registered in the brain, but when it breaks open Mind, and changes the map.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

My biggest question to the researchers in Mexico’s most prestigious University, the UNAM, who conducted neuroscientific experiments related to non-conscious telepathy using EEG, was not whether they were self-deluded, since they repeated these experiments many times over, with many different variations, achieving definitive results. My biggest question was how this knowledge could go silent, could end up meaning nothing, when in truth it is another “Copernican Revolution.” Likewise, the massive Revolution in biology regarding epigenetics, where DNA becomes not a blueprint for the features of an organism but a parabolic antenna to other fields of information “that we know not of,” is a true paradigm shift.But we still live as though we mapped out the world with that tiny percentage that translates literally into measurable qualities. The realization that water holds memory, that crystals are like software or like a transistor linked to other fields of information, should open our eyes to a Universe that we are not living in, yet. We are in a moment of mutation, extremely afraid that out recipes, our assumptions, our common sense ‒ those things that fueled our global view for so long ‒ might be one more skin that we are about to shed. The world was flat now it’s round and it will be a hologram, because each of these maps has to do with a loop that entangles a collective state of consciousness with the unending “creative evolution” in which we are involved. If we choose to remain in the cocoon of a science that considers exclusively the thing, the measurable, the concrete, and the perceivable, then we remain in the realm of a round world, a measurable, mechanical body. But the supra-biology in which we are involved seems to point towards the fact that it is time … time to imagine the unimaginable; to let the imago cells in the cocoon do their mysterious magic. Then the possibility arises that the Universe will allow everything to shine under a different light, we might well live in the “spooky action-at-a-distance” world that quantum mechanics bumped into in the middle of the night. The laws that we perceive as definite and ultimate will reveal other dimensions within a much broader context.

Matter might be experienced in full daylight as a translation of energy (not only under the subatomic microscope); energy might be experienced as a translation of frequency, and perhaps there will be recognition that there was a science elsewhere after all, in the past, and in some savage fringes of our contemporary world; but the organ for that quality of thought, for that meaning of the word “science,” had gone into atrophy in this world.

Lars Kulik: In the sixteenth century science as we know it was born and with it the idea that we could calculate the world and find the one formula to explain everything. This idea is still pushing a lot of researchers, but just a look at the number pi, makes it obvious that we will never reach the end. But we got lost in this unending search. In the face of infinity, it seems, our fear of the unknown was amplified even more. We tried to find a shortcut by using our formulas to build our own completely controlled machine world, which could be described as the technosphere. Only now are we starting to realize that the self-build crutches are destroying the world in which we are living.

Our construct of thought fools us here. With our thoughts, we construct a world in which some experiences are simply not allowed and others are exaggerated. Thus, a tremendous force falls into our thoughts. Constructs of ideas should therefore not be confined; they should be open and adaptable. These are precisely the qualities that characterize the living. Life is flexible and viable, it is built for growth and learning. It has the potency to react to new experiences and thereby preserve the known. It is not about the destruction of the old, but rather about a change that could lead to an integration of the old and the new.

To illustrate that a bit more and shed light upon the role of human beings in this world, I will take a short look at our biological history. About 3.5 billion years ago on the already 1 billion-year-old Earth developed a simply built unicellular organism, which was separated from the outer world through a cell membrane, and enclosed a complex biochemical apparatus together with the DNA. The survival of these cells was only possible by a well-coordinated cooperation of the parts. Several hundred million years later, some of these simple cells joined to become a more complex cell, the so-called eukaryote. This cell type was again several million years later the basis for multicellular organisms. Once developed, multicellularity was a flexible and viable construct. Almost all living creatures that are visible to humans without tools are multicellular organisms. The human being itself consists of trillions of cells, which in various specializations form all organs of the body.

The evolutionary history reduced to these three steps, clearly reveals a cooperative pattern. In each step, a harmonious interplay of parts forms a larger whole ‒ a new autonomous individual. The individual cells are still clearly recognizable and are connected directly or through communication. In this relational structure, the cells are differentiated for different tasks. The whole is endeavoring to harmonize these relations, given external and internal influences, so as to preserve the autonomy.

In this perspective, human beings differ very little from the countless other creatures of this Earth. The processes and the constituents are very similar, so we have hardly more genes than the fruit fly and differ only by a few percent in our DNA to that of the chimpanzee.

Humans or any other individual organisms are embedded in their environment and are in interrelation with it. Environment in the widest sense encompasses the entire world surrounding the organisms. On a small scale, their social environment is of particular importance. In this regard, it is very interesting to see how our view is gradually changing. Today, a social environment is no longer confined to social living animals; a tree also maintains social relationships within its forest. Trees share information and even resources. Trees care for each other and so a forest can even be considered as a social network.

Back to the fauna: the social interactions of bees, ants, and termites are particularly noteworthy. These insects form superorganisms in which the individual animal alone is not fully viable. Reproduction and nutrition are fully linked to the community. Within these superorganisms the single individuals are highly specialized, and undertake only certain tasks. Compared to multicellular organisms, a next level of socialization seems to be visible here. From the first multicellular organisms to these superorganisms, several million years passed again. Seemingly, plenty of time is necessary to develop well-coordinated relationships.

Modern biology is still challenged by these associations. Since Darwin, the principle of competition has been the prevailing concept. Currently more and more findings allow a different perspective. It seems much more likely that cooperative interaction determines the evolution and the life of animals and plants. Cooperative behavior is described in more and more species. In the wild and in numerous experiments, spontaneous helpfulness has been observed in our closest relatives. Cooperation seems to be a common basic principle of life. Through cooperation and the formation of relationships, new wholes are created and thereby an enormous variety of life unfolds.

This diversity does not appear to be loosely side by side; it also represents a relationship structure in which each part has a meaning for the whole. The observation of re-immigrated wolves is particularly impressive at this point. Wolves had been displaced by humans from many areas. Now, however, the wolves are coming back, which in itself is a good development, but additionally it was possible to observe in a national park in North America the influence of an animal species on the overall structure of the park. Since the Wolf population has been re-established, the biodiversity in the park has increased. Even some shore plants can be observed again. Who would have guessed that the presence of wolves would affect the flora? This makes it clear that the wolf is not to be reduced to a single function. Its effect is much more comprehensive than a simple predator‒prey scheme describes it. To see the wolf simply as a predator, and thus to perceive it rather as something dangerous does not do justice to its actual significance. He tends to be more a game warden who keeps the forest healthy. This example reveals a further aspect, namely, how our stories and thus our world view influences our actions.

And it is possible to rename something else with this example; entire ecosystems can be considered as a whole also, in which the parts equal to the cells of the body form a new being. We are thus in an organismic view of the world. This is not new, but it has a hard time in a world thought more as a machine. From my biological, of-the-living-shaped point of view, it promises to be closer to reality. Above all, it helps us to perceive our world differently and to recognize the importance of the whole and its parts and the importance of dealing carefully with them.

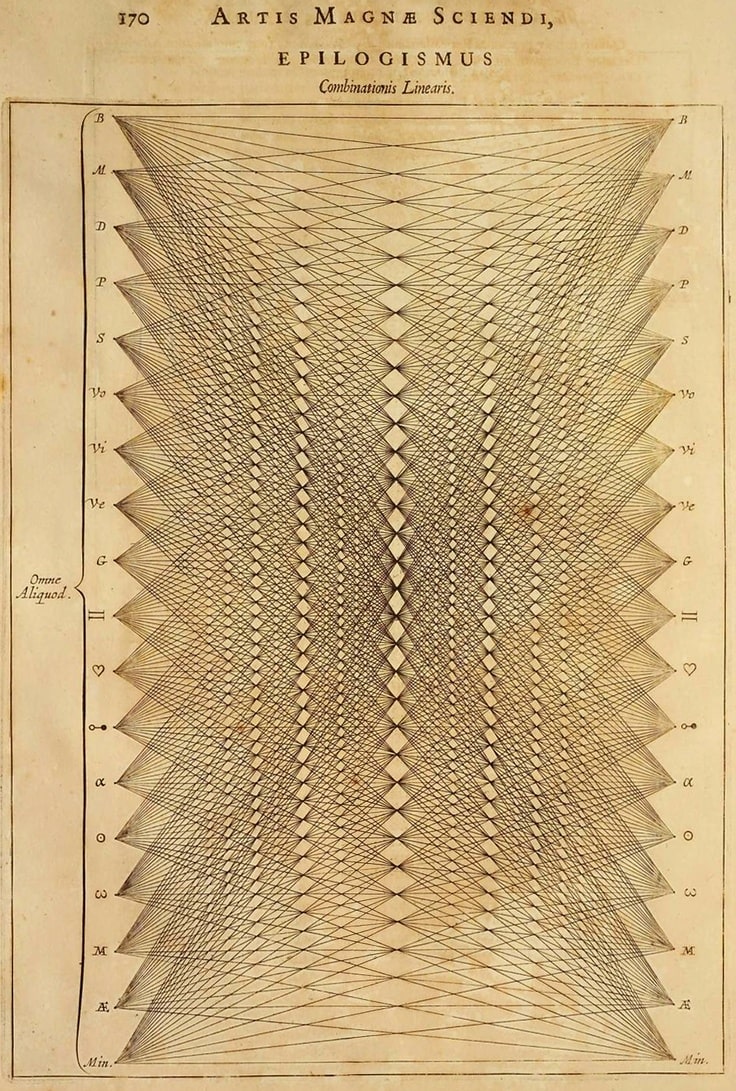

The whole appears like a puzzle, which makes only the harmonically formed complete picture visible. In this picture, however, distinct patterns are recognizable at all levels, true to the hermetic law: “As above so below and as below so above.” In science, it was called the fractal structure of nature.

Each new entity appears to be able to offer new degrees of freedom and thus to promote the respective autonomy. The larger the autonomy, however, the more it can disturb the harmony of the entire structure. The effect of human beings is a prime example and is described extensively in the idea of the Anthropocene.

These immense effects seem to underline the exceptionality of the human. But aren’t all species, even all individuals unique, like individual snowflakes? The emphasis on our exceptionality and our seemingly creative God-like powers, which manifests again in the idea of the Anthropocene, seems necessary to our self-image. Through these peculiarities, we rise above the whole and become the ruler of the world. Perhaps this emphasis, however, is only a narcissistic expression of our anxiety to perish in infinity meaninglessly? How can we incorporate our special qualities, which are present without doubt, into the whole, while countering our fears?

Our greater consciousness of the processes and structures gives us more freedom than any other creature before. This could lead us to a more responsible way of acting, but it seems that we deal with our consciousness rather clumsily and narcissistically. Although we have well-trained cognitive abilities and have implemented them in numerous technical inventions, we recognize that they have rather injured the environment more than enriched it. With an organismic view it becomes clear that we have neglected the relationships between the parts, we have divided not associated, we have scattered and not brought together. For our inventions, we have rather cut holes into the overall picture than integrated the parts appropriately.

Perhaps our task in this world is to use our consciousness in such a way that it serves the whole and thus even increases its overall consciousness. This requires, above all, a greater relational ability and a deeper insight into our embeddedness. To connect ourselves to the world around us could help us overcome our fears.

We as human beings must develop a relationship with the world around us but also with ourselves.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

François Bucher: The symphony of frequency, energy, and matter that constitutes a living entity is played out at another level when we zoom out to the collective field ‒ “human.” The human needs to become a resonating tune, to tune in.

Mamo Lorenzo, from the Arhuaco people of La Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, taught me that every ten steps we take, it is as if we were in another cell of the planet; therefore the peoples that originate in a certain node of the territory are entangled with the elements of their birthplace: plants, animals, telluric forces, astrological coordinates, and other companions, which we will not try to bring in here. The frequency of the words they utter, the foods they eat, the parts of the body they use to plant their crops, the phases of the moon on which their crops are planted and reaped (there are sixteen-year-long phases in this system); the code that is written on their traditional garb, are all reflections of a particular cosmic origin, which belongs to an ever-expanding fractal architecture. Also, the codes by which they manage the libidinal forces at a microscopic and a macroscopic level, the procedures and rituals by which their medicines are cooked, the plants they chew or smoke while they engage in ritual word exchanges that constantly reestablish a social order; all these elements, in turn, form and shape the body of the community, in harmonic vibration with the land. Every one of these elements ends up related to their cosmoexperience, which incorrectly we call cosmovision within our objectifying paradigms. A cosmoexperience is an experiential relationship with the patterns of the Universe, whereas a cosmovision entails an abstraction: the observation of laws that “govern” bodies. As Rupert Sheldrake likes to point out, this metaphor, of juridical terminology – “governance” as applied to nature ‒ is an operative fiction, but we soon forget that it was meant as a metaphor.

The science at the core of this cosmoexperience sheds light on the relationship between myth and origin and what this origin actually means in the present tense. The part that was new to me, one who had always insisted on the common matrix to all origin myths, was the emphasis on a “complementary difference” related to a location within the territory. The question of a place in space and time, “where the sun impregnated the Earth,” and which gave birth to a particular tribe, is crucial to understanding the architecture about which they speak.

What is the nature of this fractal, macro, “multicellular organism,” as we zoom out, to the collective word “human”?

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

The cells of the mouth might be exactly like the cells of the eyes, but the two organs have a different function. Therefore, as the Arhuacos see it, there is a supra-system where the people from a certain node of the territory (where the sun impregnated the Earth) are in a relationship to other tribes that are complementary to them, in the same way as the eye depends on the mouth and vice versa. In their understanding, the broken links between these tribes need to be healed for the Earth to have a chance to “raise its frequency.” But before the links are re-established the reconnection to origin is of great importance, to understand what function the part has within the whole. In this cosmoexperience there is no “other” to the human, meaning that the Earth’s metabolism is tightly woven with the human, in full complementarity. Thus, there is no “carbon footprint” instrumental-type idea in this conception, which might heal the wounded riverbed or the barren mountain. It is a much more complex experience, where what is diagnosed in the ecological disaster is the direct product of separation, resulting in incoherence and cacophony, springing from within human behavior today. It all starts with sexuality: from that seed onward, each aspect of life needs to enter a zone of coherence, allowing the system to raise its frequency as a whole. Sexuality is either a connection or it is a zone of exploitation and war. Re ligare is a plausible etymology of the word religion, to bind; and sexuality is at the core of the religious multiverse. The mutation to an evolving, harmonious frequency of the Earth does not stand a chance if the “order of everything” is not discovered anew by the human, and set in motion again. This order cannot be found anywhere but in its reflections, which is the riddle of knowing through the path of unknowing that makes every initiation into a school of mystery a de facto secret, and not by anyone’s choice.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

There are triangles drawn on the territory of Colombia by Mamo Lorenzo, these link the different tribes that originated in different locations, and all have specific characteristics in this invisible matrix. Together they become linked to other broader constellations. The consciousness of the peoples of the mountain range, the jungle, and the coast need to be combined for the body of the land to be a healthy, conscious body. These three, in their turn, will have a relationship with another set of constellations, and so on and so forth in a fractal way, creating a larger coherent body. When each collective consciousness comes into this Congress, they bring a particular energy to play with other complementary energies, to form the new hyper-body of the land, which slowly awakens to itself. It is a kind of acupuncture, which revitalizes the land as a whole. Before this vortex is set in motion the land is unconscious, and so are the humans, the plants, and the animals, that live on it. The human is integral to the Earth, according to this uncommon sense, but it is a very far call from how Western ecology views it. No one is looking from outside with a sheet of statistics, in this experience HUMAN is fully attained as another star of a limitless constellation, both a mirror and a generator of the consciousness of the Universe.

In these peoples’ cosmoexperience the tipping point that we are going through was always foreseen: the consciousness of the Earth was understood as needing to go through its own cyclical labor and beget itself as a new consciousness in an untold dimension. I have met many wisdom keepers who quote their elders as saying there would come a time when the white man would come back “asking who he is,” and that they had to keep the knowledge guarded until that time. That time is now. They had also warned that the keepers of this wisdom should be very watchful not to deceive this “white man” because his question would have become sincere by then. All of this information is coming out today, it is being offered to the Western world because the tipping point is upon us, and they can no longer remain secluded with this knowledge in the face of the times that are ahead of us all. The science that is now offered to the “white man” who comes by, asking humbly who he is, is not an imprecise, fluffy fantasy, as we always liked to think, it is a robust science. It is pregnant with a reflection ‒ like a pond under a starry night ‒ of what the people from La Sierra would call “the order of everything.”

The question of the cell making up the organism, leading to the supra-organism, is not only a spatial question but also one that has to do with time. We speak here of time as a dimension, not as a linear concept ‒ and this is why it is crucial that in the world of the Mamos a person makes peace with the 126 ancestors they carry epigenetically. Before the real work begins, an individual needs to heal from atavistic fears, and from the very nature of separation that is encoded in those fears. In order to access Love, the kind of Love that raises the consciousness of the Earth and that builds a “coming community”; that integrates thought from the head and the heart together in one; and therefore is connected to the Heart of the living Earth. This integration has never happened before quite like now, as we face mass extinction or the biotic crisis. Beyond the critical passage through the Pandora’s box of the Anthropocene concept, we might now imagine a new Era where the word “evolution” means something akin to partaking in lifting up the consciousness of the Earth in relationship to the solar system, the galaxy, and the Universe.