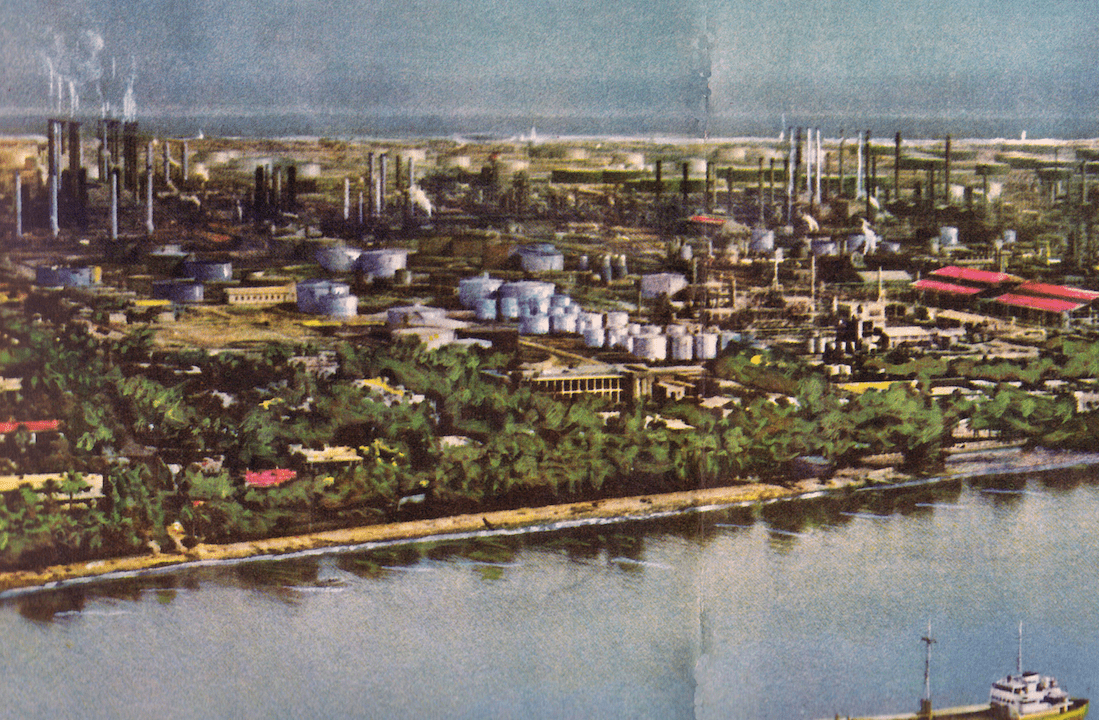

Iran Today 1960

A view over the Abadan city and refinery

Port Cities: Nodes in the Global Petroleumscape between Sea and Land

Mapping the interplay between oil corporations, coastal regions, colonial and post-colonial politics, historian of architecture and urbanism Carola Hein investigates the establishment, transformation, and possible future of the global petroleumscape. The result is a portolan chart of the networked infrastructure of extraction, refining, transport, and storage by which the open sea faces the continental hinterlands.

Each city receives its form from the desert it opposes; and so the camel driver and the sailor see Despina, a border city between two deserts.Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili. Torino: Giulio Einaudi Editore,1972; trans William Weaver, “3: Cities and Desire”in Invisible Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1976.

Like the imaginary Despina, port cities have two sharply differing faces: facing the sea, they are industrial and globally identical, and facing the land, they are multifunctional and locally integrated. Global petroleum has long been a critical agent in shaping port cities’ global geographies, which are simultaneously maritime, urban, and rural. Its infrastructure at major production and transformation sites punctuates networks of consumption, and the industry is sustained by intangible, international flows of finance and ideas. This confluence of politics, economics, and geography has produced a single, but layered landscape—a palimpsestic petroleumscape. Port cities are key nodes in the flows of petroleum, where kilometers of oil infrastructure ‒ including storage tanks, refineries, and pipelines ‒ occupy prominent spaces. They are paradigms of the petroleumscape.

Oil Ports from the Sea and from the Land

Viewed from the sea, oil ports are almost uniform, characterized by almost identical industrial structures. Refineries, storage tanks, and pipelines signal the presence of global petroleum flows. They can serve incoming vessels whether they carry oil or refined products, and no matter in which direction the vessels arrive. These structures illustrate how industrialization has served as a global equalizer, and both the production of petroleum products and its consumption showcase globalization. While the petroleumscape within the port is particularly visible and notably similar everywhere, it produces a second urbanism in the port city and its hinterland, that is more diverse and features local adaptation. That is, viewed from the land, the uniformity of the port city’s industrial petroleumscape dissolves. Diverse actors, global, national, regional, and local negotiate a distinctive presence in the port city and region. Throughout the twentieth century, as oil companies (and states) sought to transport oil from production sites to refineries, and, ultimately, to the consumer, they expanded their distribution networks by building railways, roads, and pipelines to access the hinterland in the United States, Europe, Russia, and the Middle East.

Port cities have become petroleum nodes on every continent because corporate and public interests collaborated on various parts of the supply chain, from oil extraction to transportation to transformation and resale. Refineries and other petroleum facilities thrived in proximity to the port, at the transition point between water- and land-based infrastructure generally. Oil infrastructure overlapped here with other aspects of the dynamic, multi-scalar, and interconnected petroleumscape, including transportation, administration, and consumption. Rotterdam is just one example, with its oil-related infrastructure spanning the inner city to the tip of the port, the Maasvlakte II terminal (Fig. 5 at the end of the text). Almost identical oil facilities are situated along the shores of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, or the Elbe River in Hamburg. Port areas around the world, from Dubai to Singapore, from Abadan to Port Harcourt, display similar structures.

Parallel Stories in Global Oil Ports

Investments in expensive infrastructure have guided petroleum flows for over 150 years. We can trace this history in the ups and downs of Philadelphia’s refineries along the Schuylkill RiverCarola Hein, “Refineries (Oil),” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (2016). Philadelphia, NJ: The State University of New Jersey (http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org). (Fig. 2). Already an industrialized port city with global networks, and boasting extensive under-developed available land along the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, the city offered the new industry the necessary rail- and water infrastructures as well as access to water. New refineries, storage tanks, pipelines, and railway lines constructed in the late 1860s amidst apple orchards, made Philadelphia a global player. In Pennsylvania more largely, private owners and state-funded entities had built long-distance railroads to carry anthracite coal along the course of the Schuylkill River to Philadelphia; now they transported oil from the oil fields to both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Seafaring vessels carried petroleum in barrels along the coasts and across the oceans. Standard Oil, which sold kerosene for lamps in China as early as the 1890s, owned its own fleet of ships. This fleet also carried oil from Philadelphia to Shanghai and other treaty ports in Asia. By 1912, petroleum had become “one of the most important industries of Philadelphia.”John James Macfarlane, Manufacturing in Philadelphia, 1683‒1912: With Photographs of Some of the Leading Industrial Establishments. Philadelphia, NJ: Philadelphia Commercial Museum, 1912, p. 65. Oil export was closely linked to the shipping business, and by 1912, the Philadelphia port was in its heyday. After companies finished consolidating the refineries on a handful of sites, notably on the Schuylkill, the presence of the oil industry continued to influence spatial decisions, and continues to do so to this day.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Petroleum has had a similarly strong and transformative presence in many other port cities. With the beginning of commercial oil extraction in Western Pennsylvania, corporations quickly reshaped cities and landscapes, initially for the benefit of the oil industry, often with support from public entities. All the ports along the Northeast European coastline, from Hamburg to Antwerp, received petroleum from the United States, often via Philadelphia, from the 1860s on. Petroleum entered the markets of Germany, The Netherlands, and Belgium, first as light oil, and later as benzene for cars. Indeed, corporations and public entities again reshaped landscapes to facilitate the consumption of gasoline by the growing number of cars. Among all these changes, production for local consumption was not the only goal; the industrial petroleumscape in the port cities stretched out its tentacles to the hinterland, often serving other countries beyond national boundaries. Private companies built railway lines, pipelines, tunnels, bridges, and even airports in their attempt to facilitate trade.

The relationship of port and city, of water and land-based infrastructure, became a major element in a company’s choice of location for its refining infrastructure. In the case of Rotterdam, cities expanded to serve the needs of oil companies. Here, the de Monchy family of merchants owned the firm Pakhuismeesteren, the first company to store petroleum in the city.Huibert Schijf, “Mercantile Elites in the Ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, 1850–1940,” in Carola Hein (ed.), Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks. London: Routledge, 2011.; Vopak, Onze historie. https://www.vopak.nl/onze-historie (accessed March 14. 2017) The economic elite were closely associated with political brokers, including those driving the annexation of Charlois. After several years of negotiations, in 1895, Charlois officially became part of Rotterdam, and the oil storage and trading center.Arie van der Schoor, De Dorpen Van Rotterdam: Van Ontstaan Tot Annexatie. Rotterdam: Ad Donker Publishing, 2013. By that time, the urbanized area in the Western Netherlands, also called the Randstad, where railways had first connected the main cities on the Western shore, saw the construction of railway lines towards the German industrial areas just across the border, lines that would also come to serve the oil industry. In the competition between the Northwest European oil ports, this connection would be of key importance. Over time, Rotterdam would first bypass Amsterdam and Antwerp and then later the North German ports (Fig. 3). It created the foundation for the long-term development of Rotterdam as an oil port just at a time when new global players in oil emerged.Carola Hein, “Rotterdamse Olie-Industrie in Historisch Perspectief,” 2016, Europoort Kringen (http://www.europoortkringen.nl/?s=Carola+Hein); Carola Hein, “Analyzing the Palimpsestic Petroleumscape Of Rotterdam,” Global Urban History Blog, 2016 (https://globalurbanhistory.com/?p=2071&shareadraft=57ea1be60f827).

As inventors created new uses for petroleum products and as companies aggressively brought them to market, oil became a dominant resource in daily life around the world.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Simultaneously, oil companies and states sought to assure transportation of oil from the production site to the refinery and, ultimately, to the consumer. Colonial empires grew around oil networks. Cities like the oil port Abadan in the province of Khuzestan in Southern Iran where a refinery was established in 1911, and other towns built by the Anglo-Persian Petroleum company (later named Anglo-Iranian Petroleum Company ‒ a predecessor of British Petroleum (BP)) in the early 20th century to produce, transfer, and refine oil, illustrate how modern technology in the port served as the basis for introduction of foreign lifestyles through housing for expatriates and workers, or new urban amenities such as swimming pools, hospitals, and members’ clubs.

The end of Europe’s colonial empires and subsequent post-colonial nationalization coincided with the expansion of the United States’ global oil interests and its related restructuring of global networks and transportation infrastructure. As oil became more important to the national interest, many oil-rich countries nationalized oil reserves and foreign-owned infrastructure, including refineries, at times using the resulting new wealth to create new infrastructure, including new capital cities. Then, as the former colonial powers had to leave, oil companies rebuilt refineries back home, but remained involved, where possible, in the post-colonial oil business. The case of Nigeria exemplifies the entanglement of global oil companies in post-colonial oil exploration and the development of new urban structures, including new ports in exporting countries. Royal Dutch Shell (as Shell D’Arcy) discovered oil at Oloibiri in 1956, and Nigerian crude oil was exported from Port Harcourt after 1958.Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper (eds), “Between Oil and Water: The Logistical Petroleumscape,” in The Petropolis of Tomorrow. New York: Actar/Architecture at Rice, 2013. The petroleum industry sparked urban development in Port Harcourt and the conception and construction of the new capital city, Abuja, in the center of the country, as well as the growth of Lagos Port, through which consumer goods and raw materials entered the country. The impact of petroleum exploration thus extends beyond production sites to locations of administration as well as to new urban developments and investment of oil funds: an urbanism fueled by oil.

As oil networks expanded, new producers created additional oil ports featuring well-known industrial features, thus developing yet another set of relationships with neighboring cities. In the 1970s, Sheikh Rashid constructed Port Jebel Ali in Dubai to compete with a neighboring emirate and to secure oil profits.Stephen J. Ramos, “Dubai's Jebel Ali Port. Trade, Territory and Infrastructure,” in Carola Hein (ed.) Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks. London: Routledge, 2011. He used foreign ideas and consultants for engineering, planning, and architecture (including concepts for company towns), reinventing and reimagining the port city at a new, unprecedented scale. The governments of the new global players, such as China and Russia, are directly involved in the economies and spaces of the regions of oil flows; they plan the spaces for oil as part of the urban infrastructure and function of the neighboring city and region. Public and private partners have the capital and the resources ‒ but not necessarily the incentive ‒ to contribute positively to the process of planning and overcoming the petroleumscape.

Petroleum Ports beyond Oil

Changes to petroleum activities and requirements have had a major impact on cities, and by extension, to the ports that serve them: from the use of the waterfront to the construction of infrastructure, company headquarters, and housing facilities. Some of this infrastructure, such as the railways and road networks, has survived and shaped later patterns of use; others, such as shipping routes, have disappeared with little trace. Today, petroleum interests are again shifting the locations of their infrastructure, leaving behind spaces that will require redevelopment, and forever transforming new areas. They are moving exploration and production facilities ever further out to sea, rebuilding and revamping refineries, and bringing new greenfield refineries to life.

These transformations present states and cities with new opportunities for comprehensive planning, including careful consideration of their environmental impact and potential as redevelopment and heritage sites. Some of the abandoned areas can be reused for other activities, but the pervasive quality of oil interests, and the economic and environmental burden of the cleanup, often prevents cities from liberating centrally located spaces. Over the decades, for example, the industrial complex in Philadelphia has become an obstacle to urban development. When use of these refineries was declining, the high cost of cleaning up the highly polluted sites prevented the city from closing them (Fig. 4). In 2011, a new urban future seemed to be in sight after the American petroleum and petrochemical manufacturer SUNOCO threatened to close its struggling refineries on the Schuylkill River.Dealbook, “Sunoco to Sell Refineries,” The New York Times, September 6, 2011 (http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/09/06/sunoco-to-sell-refineries/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0). Andrew Maykuth, “Sunoco to Sell or Close Its Refineries in Philadelphia, Marcus Hook,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 2, 2011 (http://www.philly.com/philly/business/20110907_Sunoco_to_sell_or_close_its_refineries_in_Philadelphia__Marcus_Hook.html). But a shale oil boom in the US revived the company’s financial viability,“Revived Sunoco Refinery Could Be Worth $1 Billion Plus,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 6, 2015 (http://www.philly.com/philly/business/20150806_Revived_Sunoco_refinery_could_be_worth__1_billion_plus.html). as Bakken oil started to be brought in by rail from North Dakota.Energy Information Administration, 2015, “Total Crude by Rail” (http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/2015/04/01/105014309b.png). By January 2015, more than 33.7 million barrels of crude oil were transported by rail in the US, fifty times the amount that had been shipped five years earlier. Having tanker railcars regularly run through a city of 1.5 million inhabitants in a metropolitan area of some 6 million is to invite trouble. No major accident has happened so far, but the only reason to transport oil through a densely populated metropolitan area is to maintain a refinery established more than a hundred years earlier. Discussions of Philadelphia as an energy hub or a green city contend with the inertia of the oil infrastructure that, once established, draws oil flows even into regions that would not attract such flows today.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

In Rotterdam, innovative refining technologies blocks cities from reclaiming these sites in the near future. Today, BP refinery in Rotterdam, which started production in 1967, includes facilities at Europoort and Pernis. Its production capacity of 400,000 barrels of crude per day with a storage capacity of 4.5 million cubic meters illustrates the growth of the industry. Today, five refineries are located in the port of Rotterdam, and several more are connected to it: Total/Lukoil in Vlissingen, Shell in Godorf, BP/Rosneft in Gelsenkirchen, and Total and ExxonMobil in Antwerp, make the port of Rotterdam one of the largest petroleum nodes in the world. The Clingendael Institute, a Dutch think tank, recently evaluated the refineries in Northwest Europe and concluded that many of the installations in Rotterdam and Antwerp were so-called “Last Man Standing” or “Must-Run” refineries.CIEP, “Long-Term Prospects for Northwest European Refining. Asymmetric Change: A Looming Government Dilemma? With contributions by Robbert van den Bergh, Michiel Nivard, and Maurits Kreijkes. The Hague: CIEP, 2016. The existence and staying power of the Rotterdam oil port may mean that fossil fuels will be directed there even while other refineries close, unless the port players opt for a different strategy.

Despite the growing crisis of climate change, the growth of new renewable energy sources, and the need for circular economies aimed at a long-term use of materials, and at recovering and regenerating products at the end of their lifecycle, the oil era will probably not end soon. The critical role of shipping and ports in global petroleum commerce thus will also likely continue into the future. Ships continue to be the main form of transporting petroleum across the world’s oceans. Even pipelines ‒ within continents, as an alternative to shipping ‒ are often linked to ports because ships navigate the oceans. The global rise in sea levels particularly challenges port cities and the historic locations of refineries, yet another dimension in the relationship between water and oil.

As we become more aware of the ways in which oil logistics produce similar spatial templates in port cities and elsewhere, and how those templates linger beyond their original function, the re-planning of this technosphere merits greater consideration. In appreciating the power of and extent of oil, we can engage with the complex challenges of creating sustainable architectural and urban design and policy, developing novel concepts for the heritage of oil, and meaningfully imagining the future of built environments beyond oil. It remains to be seen whether corporate and governmental players that control oil can re-design coastal cities in anticipation of broader cultural needs and uses. Democratic intervention and public input are needed to address the distinctiveness of each port city and its hinterland, designing its own way forward past identical global challenges of overcoming oil.

large

align-left

align-right

delete