A Caribbean Taste of Technology: Creolization and the Ways-of-Making of the Dancehall Sound System

The Caribbean has long been considered a melting pot of Old and New Worlds. Writer, director, and cultural researcher Julian Henriques looks at the Jamaican reggae dancehall sound system to explore how this street technology has found creolizing ways to prevail in the neocolonial power struggle between popular culture and Jamaica’s ruling elite.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

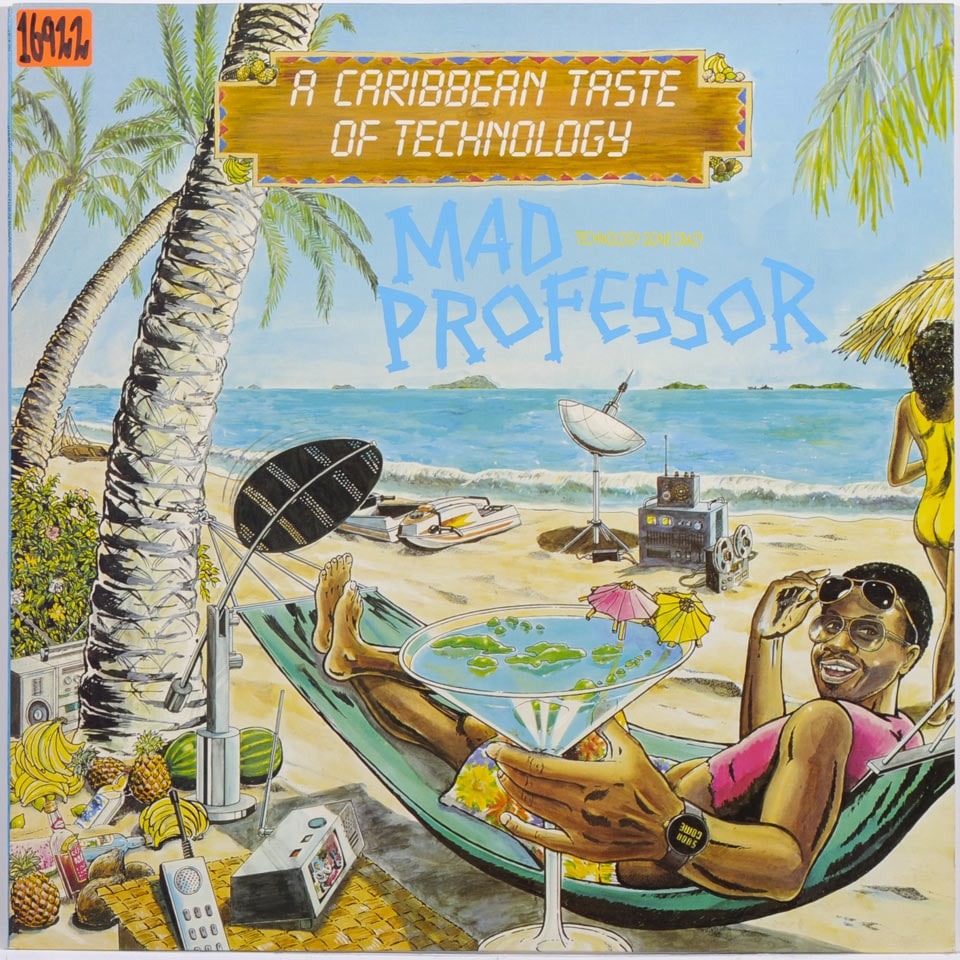

This article takes its name and inspiration from the Mad Professor’s album A Caribbean Taste of Technology in response to the theme of this Technosphere issue.The ideas for this image-essay are largely taken from chapters 1 and 3 of Julian F. Henriques, Sonic Media: Reggae Sound System Technology, Culture and Ways of Making. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, forthcoming (2018) and from J. F. Henriques, Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques and Ways of Knowing. London: Continuum, 2011. See also J. F. Henriques, Rhythmic Bodies: Amplification, Inflection and Transduction in the Dance Performance Techniques of the “Bashment Gal,” Body and Society, vol. 20, nos 3‒4 (2014), pp. 79‒112. It’s a good place to start a discussion of creolization and technology here with the dub reggae tracks of this album created by British producer Mad Professor and released in 1985. So what I present here is a text and ideas version of the album as it were.

The album cover artwork sets the tone. The Mad Professor himself lays back in a hammock enjoying the drink in his hand (the glass containing the entire Caribbean archipelago), the sun-soaked beach, and the array of the latest technological accoutrements of the era together with a selection of tropical fruits.Please see Louis Chude-Sokei’s excellent account of this album, L. Chude-Sokei, The Sound of Culture: Diaspora and Black Technopoetics, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015. The technology is evidently not a threat, but a source of pleasure; he is relaxed about it. This is the key message: in the Caribbean context new technologies are an invitation to be creative, an impulse that leads to Afrofuturism.See “Afrofuturism, Technology & Fiction,” Harold Offeh in conversation with Julian Henriques (Goldsmiths Department of Visual Cultures Public Lecture series, forthcoming) and also the talk on which it is based (https://storify.com/skindeepmag/skin-deep). This creativity is nowhere better expressed than in Jamaican music and the global influence this has in terms of sound, rhythm, and phonographic performance techniques.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Jamaican music technology – the stage show, the sound system dance, and the recording studio – provide examples of positive spin on the idea of creolization. The concept of creolization describes the mixing of cultural forms specifically in a New World setting conditioned by the disruption of slavery and forced, migration which has a long and contested history.

In post-colonial theory, the concept of creolization has been criticized for lacking an account of the power relations in which cultures are constituted.Wendy Knepper, “Colonization, Creolization, and Globalization: The Art and Ruses of Bricolage,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, vol. 21 (October 2006), pp. 70–86; also Françoise Vergès, “Kiltir Kreol: Processes and Practices of Créolité and Creolization,” in Créolité and Creolization, in Okwui Enwezor et al. (eds), Documenta 11_Platform 3. Kassel: Fridericanum-Veranstaltungs, 2003, p. 184. Stuart Hall councils that, with creolization “questions of power, as well as issues of entanglement, are always at stake.”Stuart Hall, “Créolite and the process of creolization,” in Robin Cohen and Paola Toninato (eds), The Creolization Reader: Studies in Mixed Identities and Cultures. London and New York: Routledge, 2010, pp. 26–38, 29. With the-ways-of-making of the street culture and the technology of the sound system than other cultural forms, however, this limitation might have less purchase.

While there are often skirmishes with the police, and the open-air dancehall venues are invariably shifting, the dancehall scene is comparatively autonomous and self-generating. This is because as a street technology and culture of the ghetto, its creolizing mixes take place largely “under the radar” of the authorities. This is what makes the practices of the scene such an exciting prospect for investigation in terms of the processes of creolization.

Seven key features of creolization are picked out in what follows.

1 Creolization as Bricolage: Mobile Sound Systems

large

align-left

align-right

delete

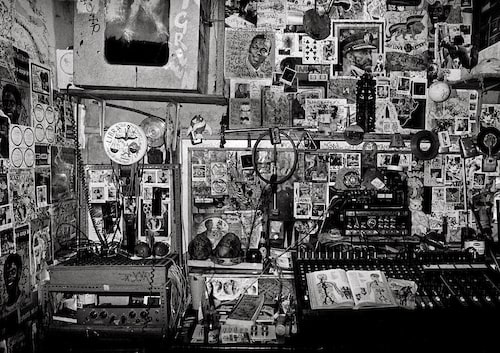

One important aspect of creolization is bricolage, as the activity of bringing together disparate components into a new assemblage. The components themselves are not new ‒ in fact they are often re-cycled or re-purposed, far from the factory setting. Their novel functionality lies in the assemblage as a whole. As a type of bricolage, creolization involves working practices of experimentation, trial and error, and ways of knowing through an in situ process of making. This contrasts with the architect or engineer executing a pre-organized plan.

Bricolage is a quotidian, one-off, personalized DIY practice that makes use of whatever materials or components are readily near-to-hand, as is commonplace in a huge range of settings across the globe.In India the practice goes by the name of jugaad, see Navi Radjou et al., Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Generate Breakthrough Growth. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. On the street, it is seldom the standard issue put to standard use – instead it is re-engineered often subverting the manufacturers’ specifications and intensions.

Bricolage often involves a repurposing of components. A good example of this would be Hedley Jones’ repurposing a telephone handset microphone as a pickup for an electric guitar of his own invention.As discussed in Henriques, Sonic Bodies. Street technology is the low art to the high art of the technology corporations.

This is vividly expressed with Charlie Ace’s Swing-a-Ling mobile record and recording shop and studio. Creolization provides local practical solutions; note that the vehicle is not only a shop but also claims to be a recording studio. The contingencies of the street culture exercise a considerable influence on the technology. Without the resources that permanent venues require, mobility is most important.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

A more contemporary version of this same mobile technology is provided by DJ Squeeze and his sound system on wheels; though more polished, it is essentially the same creolized solution of assembling the two technologies of transportation and sound system together. This of course is far from unique, with the sound floats of the Trinidad and Tobago carnival as an outstanding example. Julian Henriques and Beatrice Ferrara, “The Sounding of the Notting Hill Carnival: Music as Space, Place and Territory,” in Jon Stratton and Nabeel Zuberi (eds), Black Popular Music in Britain Since 1945. London and New York: Routledge, 2014, pp. 131–52.

Both creolization and bricolage are sources of creativity and originality of the kind found with musical improvisation, as distinct from the interpretation of a musical score. Bricolage has also proved a valuable conceptual resource for the cultural studies approach to subcultures, as with Dick Hebdige’s pioneering studies.Dick Hebdige, Subculture: the Meaning of Style. London: Methuen, 1979. The critical edge of the term comes from the heterogeneity of the components it assembles, as distinct from the operation of that which media theorists would nowadays describe as “cultural techniques.”Bernhard Siegert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and other Articulations of the Real, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young. New York: Fordham University Press, 2014.

2 Creolization as Mixing: Reggae Dub Music

large

align-left

align-right

delete

It is widely recognized that Jamaican patois and other creole languages mix cultures together to produce a distinctive new one. Similarly, the standard music studio post-production mixing technique brings together the separate tracks on which the individual musical instruments were recorded. So mixing makes the assembled bricolage of components more intense by actually merging them together – as chemical elements combine to form a new compound.

The technique of the dub mix has to be located in a New World geography specifically; that is, the recording studios in Jamaica in the 1960s and early 1970s. Its famous originators include, Duke Reid, Coxonne Dodd, Lee “Scratch” Perry, and many others. Further to a normal mix or re-mix, a dub mix, like “Buccaneer’s Cove” on the Mad Professor’s Taste album removes all but a trace of lyrics, harmonies, and instruments of the original track, to let the drum and bass predominate. To this, it adds in echo, reverb, and sound effects, copying (that’s what dub means) and doubling and redoubling back.See Julian Henriques and Rietveld Hillegonda, “Echo,” in Michael Bull (ed.), Sound Handbook. London and New York: Routledge, forthcoming. Ray Hitchens describes these studio practices in his excellent Vibe Merchants: The Sound Creators of Jamaican Popular Music. London and New York: Routledge, 2014, pp. 133–54. See also Michael Veal, Dub: Songscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae. Middletown, NJ: Wesleyan University Press, 2007. This idea of enfolding and repeating is also found in Antonio Benítez-Rojo’s concept of the repeating island in his book of that name.Antonio Benítez-Rojo, The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective, trans. James Maraniss. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

With dub, creolization can be heard as un-mixing as much as mixing, taking elements out in what has been described as a subtractive aesthetic, by contrast with the additive technique of toasting, or the breakbeat sample, that of the catchy bars.See Henriques and Hillegonda, “Echo.” Instead, the more taken out of the music track the more room it opens up for the listener to enter into the vacated space – filling it with their own associations, pleasures, and remembering of the vocal version.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The dub mix itself is then subject to the creolization of bricolage assemblage in that it is a recycling of the music track on the A-side of the 45, finding within it additional value to make the B-side dub mix. These tracks were then put together as dub albums, further adding value. As a street culture technique, invariably in a context of scarce resources, creolization is often about making more with less, or indeed something out of nothing.

Like jazz music, dub music is energized by distinctly Old World musical traditions that are often rhythmic in character, specifically Nyabinghi in respect to reggae. These ancient elements are then “reimagined” as would be said now, with the New World technologies of the recording studio, itself re-invented as a musical instrument in its own right. Thus one of the elements of creolization is that it is about the mix, literally so with the dub music mix.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The geopolitical forces of colonization meant it was in the New World that this technological mixing took place, just as it was for cultural and racial mixing, hybridity, and Latin American mestiça societies. Creolization might be contrasted with that other New World phenomenon of syncretism where one cultural form is superimposed onto another, as for example Yoruba orishas are with Catholic saints in Haitian Voodoo. The mixture of creolization said to run deeper still, in that the two elements blend to make a third can be said to run deeper than that two elements blend to make a third.

On the sound system scene, this creolization also runs in parallel with syncretic conjunctures, such as in the practice of washing inside the speaker cabinet or dusting off the mixer controls. It is a spiritual cleansing that is going on here, expressing the value system of scyence or Obeah (Voodoo in Haiti) rather than technological science.

3 Creolization as Repeating: Versioning

large

align-left

align-right

delete

A third musical example of creolization is the uniquely Jamaican musical practice of versioning whereby a single riddim (rhythm) track is used as musical backing by a number of singers and DJs. There are innumerable examples of this practice, possibly the most widely known being King Jammy’s Sling Teng riddim that has been the subject of literally hundreds of versions.For a list of versions see (http://www.jamrid.com/Riddims.php). Thus the creole cooking pot never empties however many meals it serves.

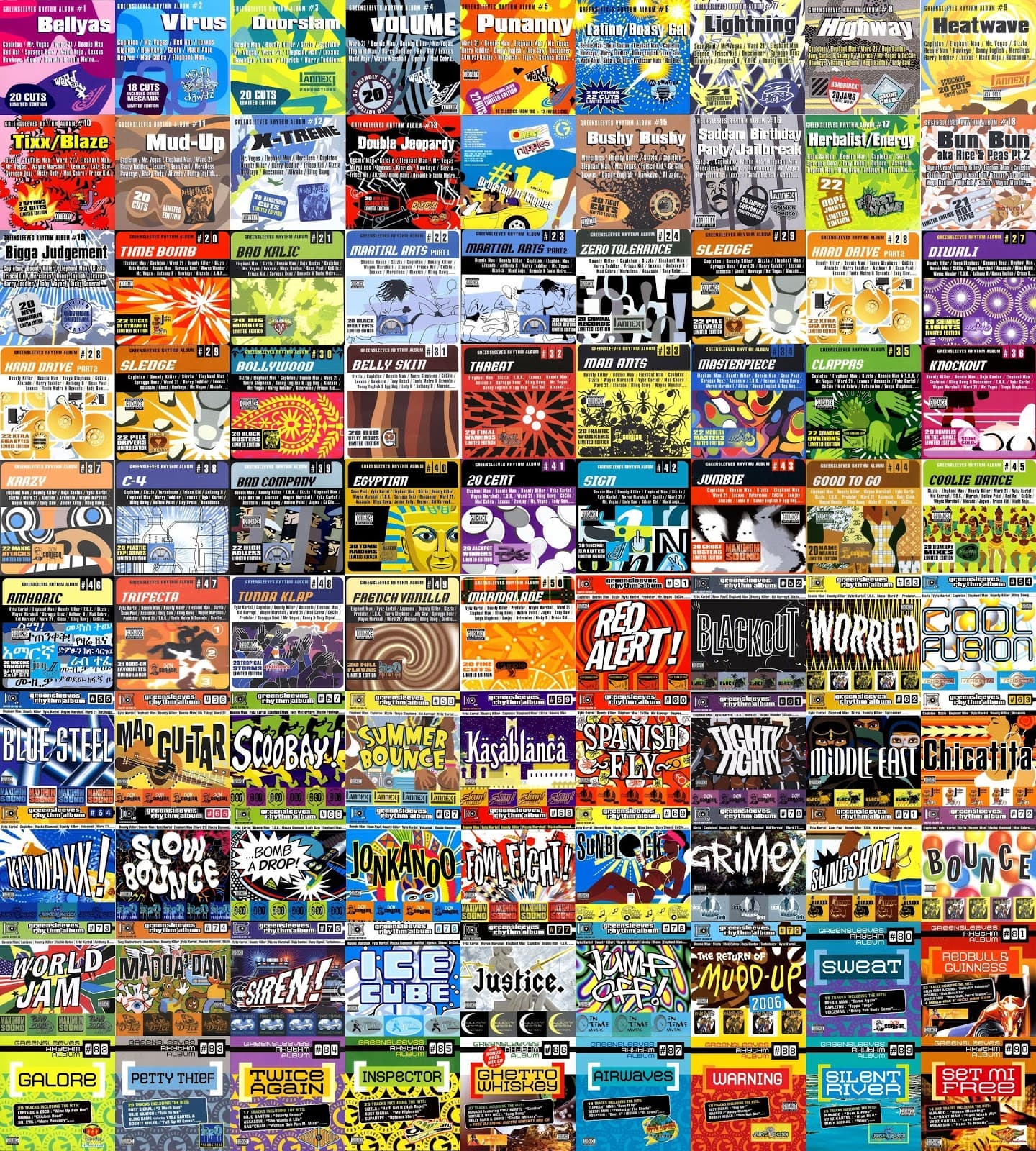

Greensleeves is one of the labels specializing in these single riddim albums. In terms of creolization this is another example of recycling a resource or component. In this instance, reiteration creates a multiplication of value. As well as maximizing the use of a resource, it also illustrates something of the distinctiveness of the Jamaican music scene where the riddim track has its own autonomy and particular importance.

4 Creolization as Socialization: Staging the Session

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

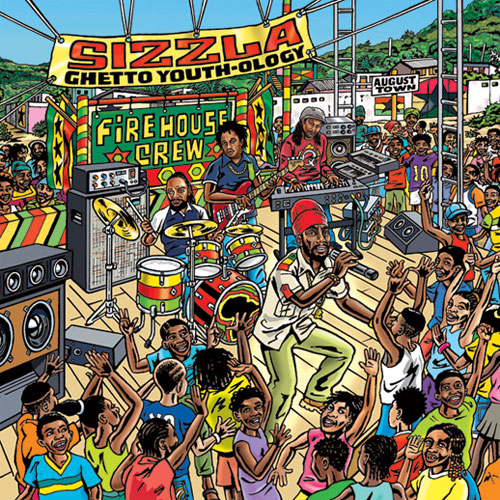

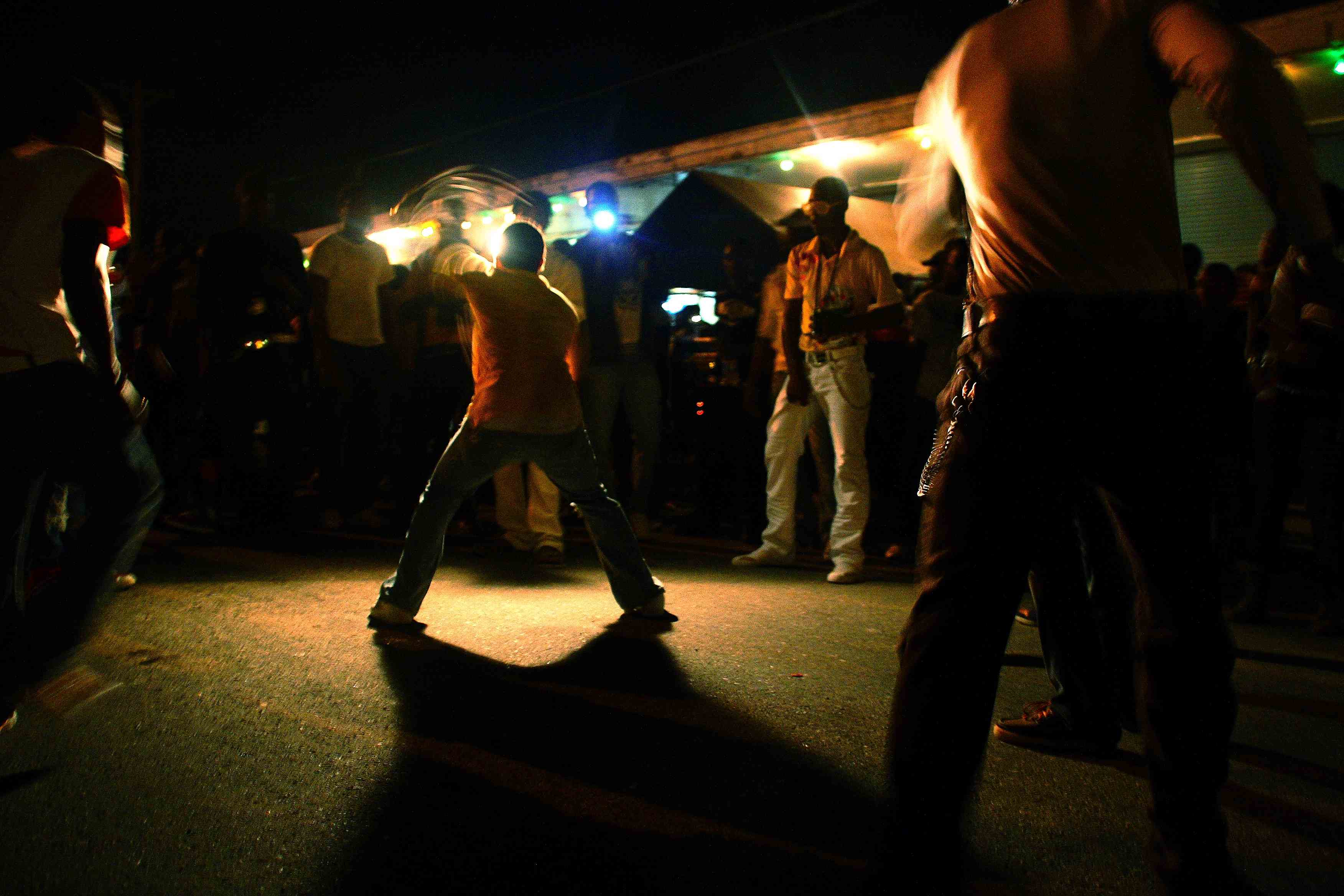

Another distinctive feature of the Jamaican music scene is the fact that the primary instrument for the enjoyment of Jamaican music is the sound system session – over and above radio, TV, streaming, downloading, CD, or even the concert or stage show. This provides an example of a fourth characteristic of creolization; that is, a repurposing of not only different technological components and devices, but also the function for which the new assemblage is deployed.

Very often creolization consists of socializing a technology, to repurpose and share what was originally designed as a domestic technological appliance to one with a much wider community of users. Thus, creolization can encourage a going against the grain of individual consumerist accumulation. The sound system exemplifies this reverse social repurposing for the phonographic instrument of the gramophone. This is what the sound system remains, but at a size and scale that an entire community can enjoy.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The sound system session draws attention to the contrast between social and individual orientated use of technologies. This has the important effect of changing the nature of the listening experience itself. The mobile personal-listening experience that was first afforded by the Walkman and subsequently by MP3 devices, inserts the music into the listener by means of in- or on- ear headphones. This contrasts with the sound system listening experience in the session. As a travelled-to destination, this is where, in the company of others, listeners insert their whole bodies into the music.

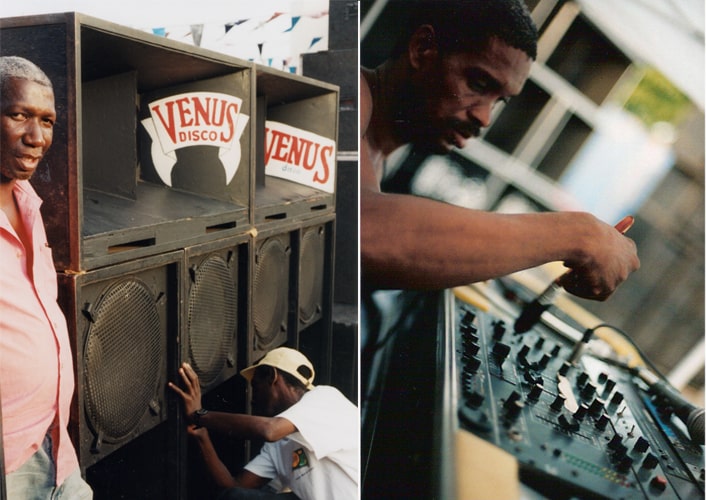

In order to achieve this, each dancehall session evening has to be transported to the open-air venue, configured in the most advantageous manner for that venue, assembled (called “stringing-up”), tested, and sound-checked. This nightly practice of assembly and disassembly for every session mimics the mixing and un-mixing of creolization.

5 Creolization as Intensification: The Set of Equipment

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The fifth characteristic of creolization is intensification, where the mixing produces a release of energy as in a chemical reaction. But this is an affective energy that could be thought as being necessitated by the extremes of the New World environment with its histories of enslavement and indentureship. In short, a creolized culture has a substantial amount of work to do reconstituting shattered identities and remembering buried histories.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

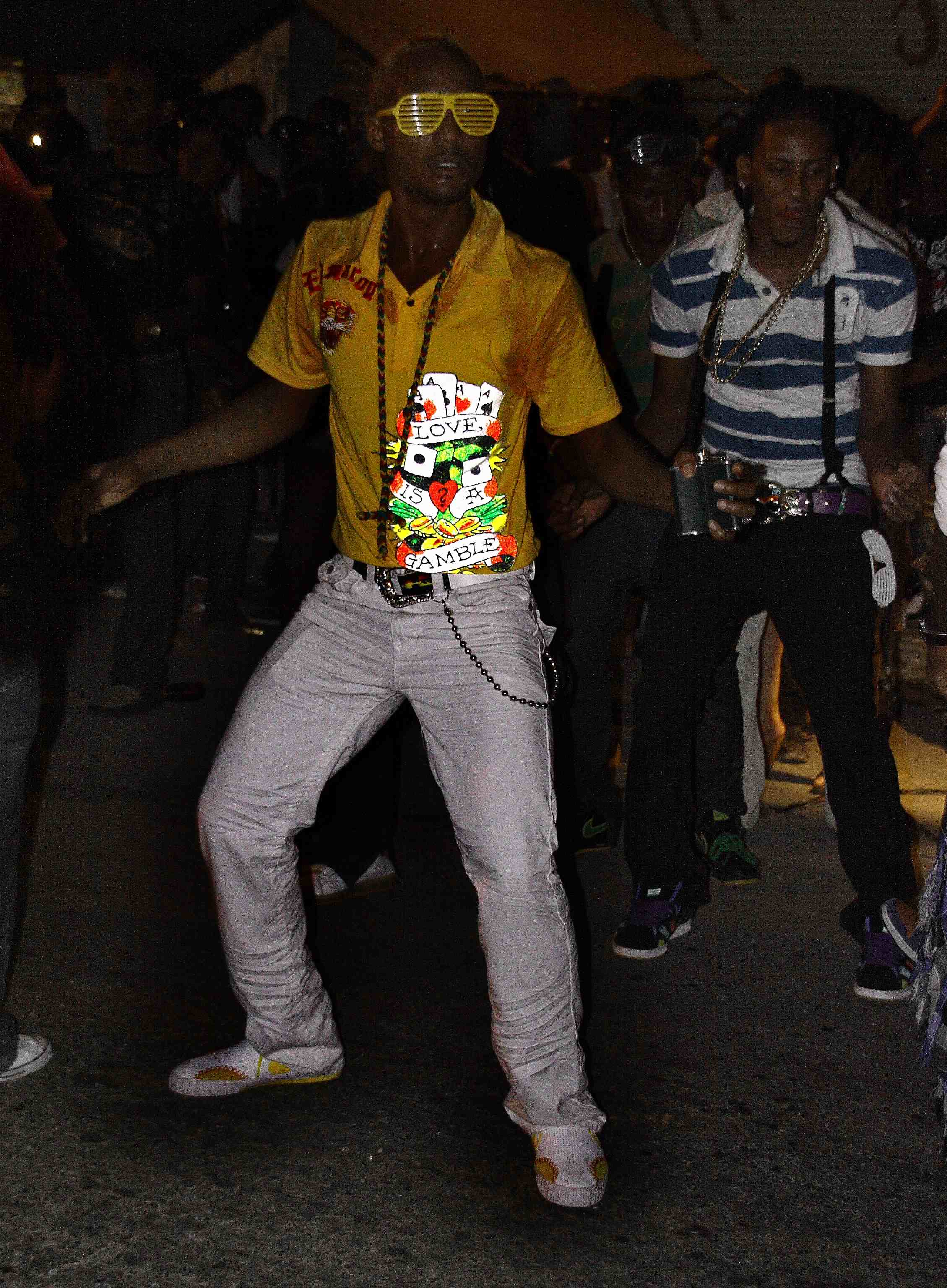

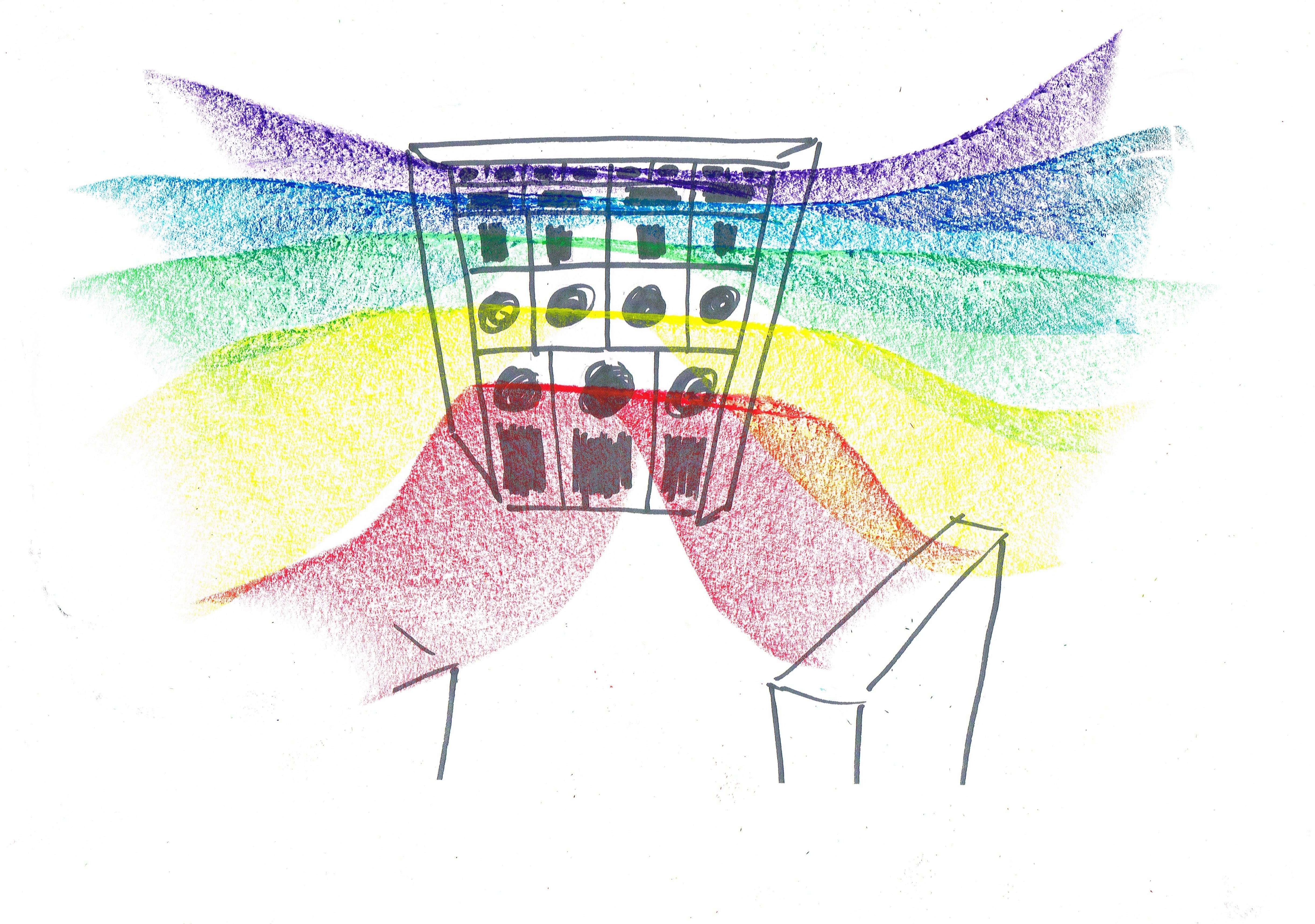

In the dancehall session, this intensification takes place in the bowl of sound between the three speaker stacks or columns. This is a special kind of place of pleasure, which could be described in terms of Homi Bhabha’s concept of a third space, or Hannah Arendt’s space of appearance.Homi K Bhabha, The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge, 1994, pp. 36–39; Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1958, p. 199. One of the ways these bass-heavy intensities are created is by what has been described as sonic dominance.Julian Henriques, “Sonic dominance and reggae sound system sessions,” in Michael Bull and Les Back (eds), The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg, 2003, pp. 451‒80. This achieves an immersive, visceral, full-body intensive listening experience, as distinct from ordinary audition via the outer ear. The physical scale and shared sociality of the sound system encourages such intensities, but again the repurposing techniques come into play. These auditory levels are furnished by the historically ever-increasing size of the amplification equipment.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The other way these intensities are created is with the inward orientation of the speakers onto the crowd (audience) in the center, as distinct from the conventional PA where the speakers are on either side of the artist on stage. This simple reorientation from outward facing to inward facing can be described as the crucial twist of creolization. Phonographic technologies are thus used to place the audience, rather than the artist, at the center of the listening experience.

6 Creolization as Separation: Frequency Specialization

large

align-left

align-right

delete

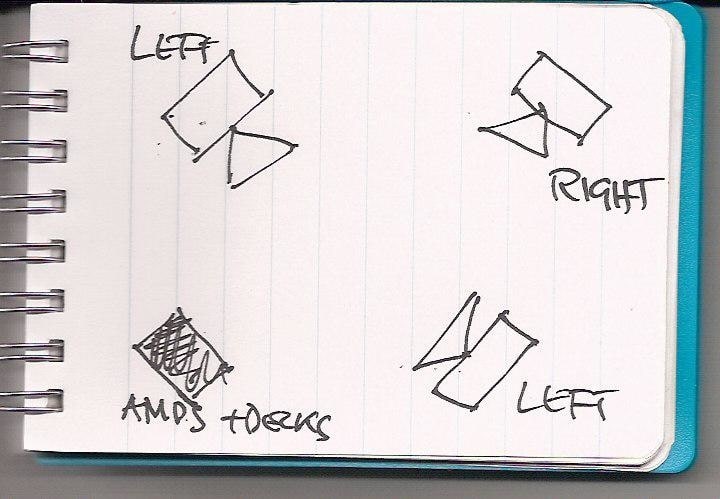

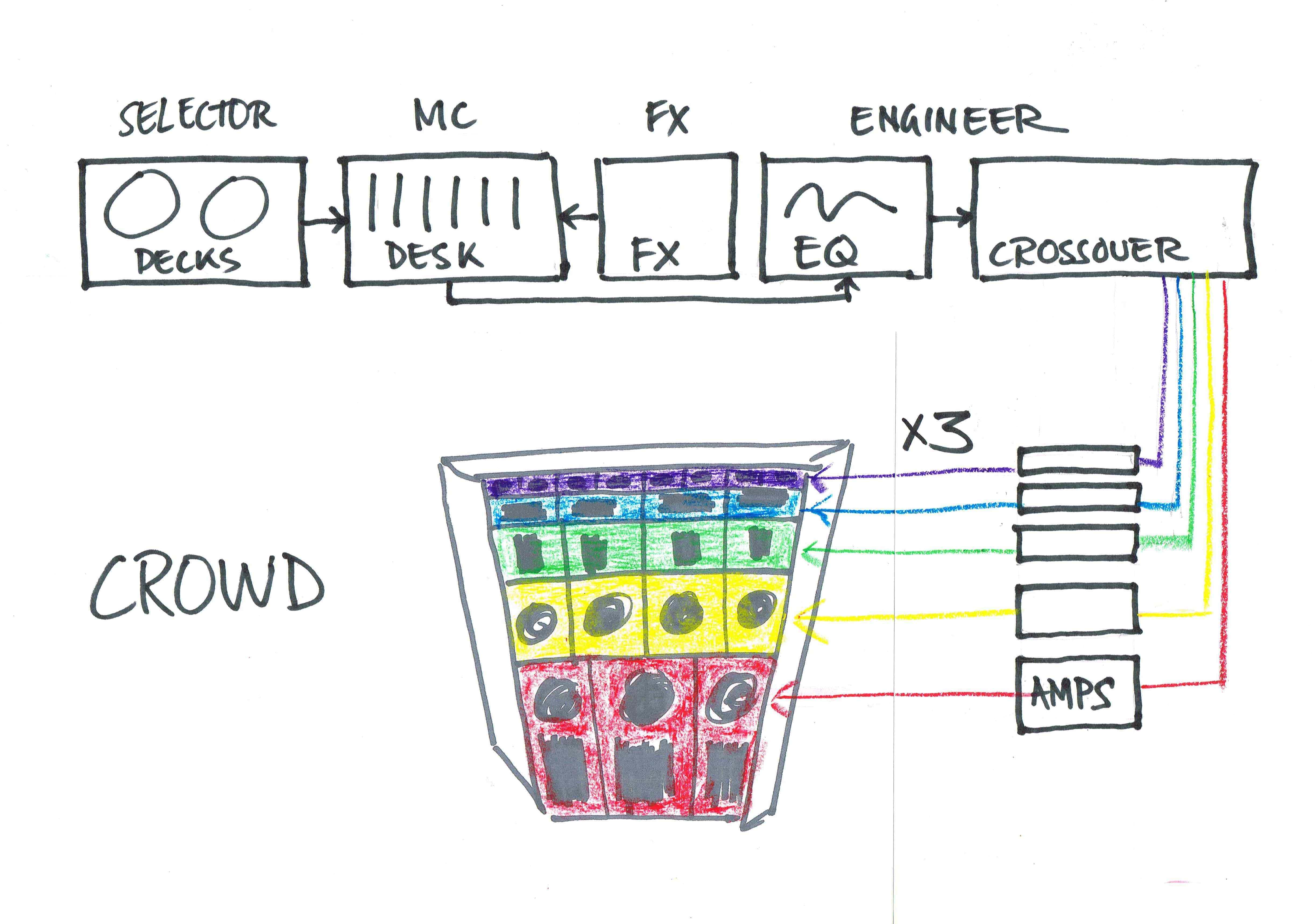

The sixth characteristic of creolization can be described as separation, that is, the kind of unmixing by which dub reggae was described. This is the case with the separation of frequencies, which is achieved by the sound system set, specifically by the crossover component. This assigns each of the five frequency bands (shown in rainbow colours) to a separate amplifier, connected to its own separate specialist speaker – from tweeters at the top, to sub-bass at the bottom. This is done for each of the three speaker stacks.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The sound system engineers who have been responsible for these innovations have taken the phonographic instrument of the sound system to new levels of sophistication. They have a nuanced, fine-grained understanding of how sound works on human bodies as much as in electronic circuits. This returns us to the starting point of the mix as the first creolization, in the way-of-making of the street technology, but transduced into the medium of auditory propagation itself.

7 CREOLIZATION AS REMIXING

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The idea of creolization has informed this brief account of sound system technology – but, at the same time, the ways-of-making technology itself has also informed what the process of creolization might be understood to be. Re-mixing can be considered as the final and seventh characteristic of creolization. Thus in addition to mixing, creolization creates value with both un-mixing as well as remixing. It is not only a music track that is remixed, but also the entire instrument of the sound system set, balanced and fine-tuned by the hands and ears of the engineers.

These thoughts on the aesthetic value of the mix take us back to the use of the word taste, the Mad Professor’s album title. The idea of taste resonates in various modalities, not least the style and the fashion of the Jamaican music scene. Taste of course is a social, political, and cultural achievement as Pierre Bourdieu taught us.Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: a Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Most importantly, taste foregrounds the pleasures of life, to be experienced, whatever your circumstances, in the intensities of the dancehall session. It is also what distinguished humans from animals – Homo sapiens (where sapiens is Latin for taste) – as Michel Serres maintains, is the sensory source of wisdom.Michel Serres, The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. London: Continuum, pp. 153‒54, as discussed in Henriques, Sonic Bodies, p. 251. A sound system session gives a pleasurable taste of the experience of a creolized technology. For me it also recalls the tingling sensation of electricity, as a schoolboy-experimenter, testing the charge of a little nine-volt battery by touching the two terminals on the tip of my tongue.