Source: Wiki Commons

Anabolic Steroids

Toxic Sexes: Perverting Pollution and Queering Hormone Disruption

What cultural nerves are triggered by the mutations of sexed biologies associated with artificially produced hormones? Evolutionary biologist and gender studies scholar Malin Ah-King and gender studies scholar Eva Hayward question the essentialist and heteronormative assumptions that frame contemporary discourses on the toxicity of endocrine disruptors.

Emerging Perspectives

The Scientific Committee on Problems in the Environment (SCOPE) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) have been diligently investigating the impact of endocrine active substances, which are known to alter reproduction and sexual morphology in organisms. The 2003 SCOPE-IUPAC report says that endocrine disruption can be expected in all animals in which hormones initiate physical change, including humans. Although the importance of low-dose exposure to endocrine disruptors for increasing human disease worldwide is contested—e.g., claims of the connection between endocrine pollution and increased infertilityBut see M. Lind and L. Lind, “Circulating Levels of Bisphenol A and Phthalates Are Related to Carotid Atherosclerosis in the Elderly,” Atherosclerosis, vol. 218, no. 1 (2011), pp. 207–13. —and some researchers even claim that the evidence is scarce, nevertheless, references to the large body of studies on disrupted animals are mounting.E. Hood, “Are EDCs Blurring Issues of Gender?,” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 119 (2005), pp. 670–77.

Among the agents culpable of endocrine disruption in ecosystems are: artificially produced hormones (steroids), which have been widely used as contraceptives for the last fifty yearsN. Langston, Toxic Bodies and the Legacy of DES. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.; other treatments in which steroids are found, such as anti-inflammatory hormone cortisol (hydrocortisone), used as an active ingredient in organ transplant anti-rejection drugs as well as asthma inhalers; estradiol and Premarin®, which are prescribed to medicate menopause symptoms, provide birth control, and other hormonal replacement therapies; and androgens, used for muscle enhancement by athletes and during androgen deficiency. Other medicines, such as paracetamol, a very common pain-relieving medicine, also have endocrine-disrupting effects,D. M. Kristensen et al., “Intrauterine Exposure to Mild Analgesics is a Risk Factor for Development of Male Reproductive Disorders in Human and Rat,” Human Reproduction, vol. 26 (2011), pp. 235–44. as do many artificially produced chemicals, such as bisphenol A (BPA), which is found in plastic bottles and containers, dental materials, paper receipts and food tins. Numerous studies claim that BPA elevates rates of breast and prostate cancer, decreases sperm count, and causes reproductive problems that include early puberty as well as other neurological difficulties.H. T. Okado et al., “Direct Evidence Revealing Structural Elements Essential for the High Binding Ability of Bisphenol A to Human Estrogen-Related Receptor-γ,” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 116, no. 1 (2008), pp. 32–38. Other agents are found in softeners in plastics, flame retardants in clothing, electronic devices, synthetic fragrances, cleaning products, and phthalates in cosmetics. Further complicating issues of toxicity, researchers also warn about the cocktail effect—whereby the combined impact of multiple chemicals may add up to worse effects than each substance on its own.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

With regard to environmental pollution, problematically, these artificially produced hormones have a longer degrading time than more naturally occurring hormones. Sewage works are not built to filter used water from drugs and other endocrine disruptors.Naturvårdsverket, “Report: Avloppsreningsverkens förmåga att ta hand om läkemedelsrester och andra farliga ämnen,” Naturvårdsverke.se, February 2008, http://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer/620-5794-7.pdf; S. Steingraber, Living Downstream: An Ecologist’s Personal Investigation of Cancer and the Environment. New York: Da Capo Press, 2010. Consequently, these substances pass through water systems and end up back in our environments.Steingraber, Living Downstream.

Although endocrine-disrupting pollution affects the whole world, it is relevant to ask which human populations are most exposed and where. Reports notify of banana plantation workers who become sterile, have increased cancer risk, and die from poisoning.L. A. Thrupp, “Sterilization of Workers from Pesticide Exposure: The Causes and

Consequences of Dbcp-induced Damage in Costa Rica and Beyond,” International

Journal of Health Services, vol. 21 (1991), pp. 731–57; W. Henriques, “Agrochemical Use on

Banana Plantations in Latin America: Perspectives on Ecological Risk,” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, vol. 16 (1997), pp. 91–99. Premature breast development in children may be due to exposure to agricultural pesticides.S. Ozen et al., “Effects Of Pesticides Used in Agriculture on the Development of Precocious Puberty,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, vol. 184 (2012), pp. 4223–32. In a report in the International Journal of Health Services, L.A. Thrupp analyzed the causes for sterilization of banana plantation workers in Costa Rica and concluded that the determinants were “dominance of short-term profit motives, and the control over information and technology by the manufacturers (who concealed early toxicological research evidence of the reproductive hazards) and by the managers of the banana producer companies.”L. A. Thrupp “Sterilization of Workers from Pesticide Exposure.”

(1991) The working classes in developing countries are experiencing greater exposure to weed killers, insecticides, industrial chemicals, and medications that are banned in neighboring countries. While insecticides, such as DDT, are banned in many industrial countries, their use is continued in developing countries, and they are spread through the atmosphere. As such, endocrine disruptors disturb multiple boundaries: of sexes, generations, races, geographies, nation-states, and species.C. Roberts, Messengers of Sex: Hormones, Biomedicine and Feminism. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

This increasing threat of toxicity has, for good reason, prompted media attention. Many news outlets are reporting these frightening endocrine tales from our backyards. In an effort to foreground these issues—as we will describe in the following—media has gaslighted a Frankenstein metamorphosis that threatens sex and sexuality. Rather than addressing the many other health risks associated with toxic exposure, the most sensational and polemical issues stand in for debate and critical response. It raises the questions:

Why is sex more central than cancer, autoimmune disease, and even death? What cultural nerves (many of which are globalized), are triggered? And, for those of us with feminist concerns, how do we reorient the debate away from essentialism, sexism, and heteronormativity?

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

Pollution Panic

Issuing a transex panic—and here, transex takes up Myra Hird’s articulation of “trans” as a biological emergence, a becoming multipleM. Hird, “Animal Transex,” Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 21, no. 49 (2006), pp. 35–50. —National Geographic published a spate of articles with titles such as “Female Fish Develop ‘Testes’ in Gulf Dead Zone,” “Sex-Changing Chemicals Found in Potomac River,” and “Animals’ Sexual Changes Linked to Waste, Chemicals,”K. Than, “Female Fish Develop ‘Testes’ in Gulf Dead Zone,” National Geographic

News, May 31, 2011, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/ 05/110531-female-fish-sex-testes-gulf-dead-zone-freshwater-environment; A. Avasthi, “Sex-Changing Chemicals Found in Potomac River.” National Geographic News, January 22, 2007, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/01/070122-sex- change.html; J. Owen, “Animals’ Sexual Changes Linked to Waste, Chemicals,” National Geographic News, March 1, 2004, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/03/0301_040301_genderbender.html. all of which champion the connection between pollution and the undermining of sexual differences.E. Hayward, “When Fish and Frogs Change Gender,” Independent Weekly, August 3, 2011, http://www.indyweek.com/indyweek/when-fish-and-frogs-change-gender/Content? oid=2626271. In an effort to raise awareness about the dangers of pollution, these write-ups rely on sensational titles that sound more like science fiction accounts of “gonadal deformities” and “sex mutations” than serious attention to environmental issues.G. Di Chiro, “Polluted politics? Confronting Toxic Discourse, Sex Panic and Eco-

Normativity,” in C. Mortimer-Sandilands and B. Erickson (eds.), Queer Ecologies, Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, pp. 199–230. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

And the panic spreads across species boundaries. Even more political progressive organizations,During recent years, many environmentalist NGOs have campaigned against sex-changing pollution. This raises important questions about the sexual politics of environmental movements: How is sexual normativity the basis of preservation and protection? This question requires thorough investigation. such as Greenpeace, have warned against the effects of commonly used chemicals in

the feminization of young boys and the masculinization of girls.

Books from environmentalists are entitled: Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening our Fertility, Intelligence, and Survival? (1997), by Theo Colborn, Dianne Dumanoski, and John Peterson Myer; The Feminization of Nature: Our Future at Risk, by Deborah Cadbury; and Our Toxic World (2013), by Doris Rapp. Barbara Seaman, in a book called The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth (2003), writes,

Nobody can be sure whether environmental estrogens lie behind the quadrupling of infertility rates since 1965; if the sea of estrogens in which we live explains the fact that sperm counts are half of what they were in 1940; and if, like intersex fish and mutant frogs, male humans might begin to morph into women.

For example, Rachel Carson’s now famous work on DDT—Silent Spring (1962)—has been advanced by Dr. Günter Dörner to say that DDT and other toxins continue to alter human reproductive systems.G. Dörner, Sexualhormonabhängige Gehirndifferenzierung und Sexualität. New York: Springer, 1972. There are also examples of how DES (diethylstilbestrol), a synthetic estrogen prescribed for healthy pregnancies, has led to breast cancer, infertility, intersexuality, and other health issues in children exposed in utero.Roberts, Messengers of Sex; Langston, Toxic Bodies and the Legacy of DES. Environmental reports also suggest a connection between endocrine disruptors and gender identity and sexuality.Hood, “Are EDCs Blurring Issues of Gender?”; T. Colborn, D. Dumanoski, and J. Peterson, Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival?—A Scientific Detective Story. London: Little, Brown, 1996.

The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation (Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen) highlighted the issue in a 2011 campaign called “Save the man!,” which drew attention to the connection between endocrine disruptors and declining sperm counts, increased number of genital malformation, postponed puberty, diabetes, and obesity in humans. These calls for response reveal a central importance given to “male” bodies and a lack of concern for women’s health problems. What is unveiled here is a preoccupation with the vulnerability of masculinity, maleness, and manhood—those precious commodities of any patriarchal system. It is not to say that there isn’t a reason for action, but again, “Save the man!” occludes many more environmental and health challenges. The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation campaign book states,

phthalates seem to have a special liking for very young boys’ genitals.R. Olsson, A. Froster, and M. Hedenmark, eds., “Den flamsäkra katten: om kemikaliesamhället, hälsan och miljön. Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen,” 2012.

Hence, human sex, particularly male sex, is described as under siege, endangered, and threatened.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

It is true that organisms are responding to pollution in their environments.T. Colborn, F. S. Vom Saal, and A. M. Soto. “Developmental Effects of Endocrine

Disrupting Chemicals in Wildlife and Humans,” Environmental Health Perspectives vol. 101 (1993), pp. 378–84; Langston, Toxic Bodies and the Legacy of DES. From polar bears and alligators to frogs, mollusks, fish, and birds, hormone-altering pollutants have affected more than 200 animal species around the world. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has reviewed reports showing interrupted sexual development, thyroid system disorders, inability to breed, reduced immune response, and abnormal mating and parenting behavior in wild animals. Recent media reports call out, variously, “Researcher: Pesticide ‘Castrates’ Male Frogs,” and “Birth-Control Pills Poison Everyone?,” and scientific reports raise alarm about estrogen pollution.“Researcher: Pesticide ‘Castrates’ Male Frogs,” All Things Considered, NPR, March

7, 2010, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124422894; ““Birth-Control Pills Poison Everyone?,” WND: America’s Independent New Network, July 12, 2007, http://www.wnd.com/2007/07/42520. Scientific reports include Colborn et al., “Developmental Effects of Endocrine disrupting Chemicals in Wildlife and Humans”; J. Kjaer et al., “Leaching of Estrogenic Hormones from Manure-Treated Structured Soils,” Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 41 (2007), pp. 3911–17; and A. Bertin, P. A. Inostroza, and R. A. Quiñones. “Estrogen Pollution in a Highly Productive Ecosystem off Central-South Chile,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 62 (2011), pp. 1530–37. In a review of endocrine-disrupting effects, the WWF states,

The effects on female dog whelk [a predatory sea snail] are striking, as they become masculinised and grow penises.World Wildlife Fund, “Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Position Statement,” WWF Global, January 2000, http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/all_ publications/?4034/Endocrine-Disrupting-Chemicals-Position-Statement-2000.

Commenting on the findings of the effect of birth-control pills on trout producing “intersex” fish with both male and female features, university biology professor John Woodling says that it is

the first thing that I’ve seen as a scientist that really scared me.John Woodling, quoted in “Birth-Control Pills Poison Everyone?”

But again, very little attention is given to how various organisms are experiencing increased rates of disease, cancer, and loss of habitat. This returns us to the earlier problem of hyperfocusing sexual anxiety around ambiguity, variability, and changeability.

What follows is our effort to provide an alternative framework that unsettles old assumptions about sex and its transformation, while providing a less apocalyptic mode of interpreting environmental change. It is not that we are promoting pollution, but rather, we are offering ways for coming to terms with the real conditions of everyday life. Rather than reinvesting in purity politics—the hope of some environmental movements—we wonder how resilience and healing can occur in the context of transnational capitalism and its monstrously underregulated dumping and pumping of various byproducts into the air, water, and earth. As opposed to simply positioning oneself as an ideologue—the world is doomed unless we clean it all up—we offer a more pragmatic, if you will, and practical theorization for understanding the organisms we are becoming and the changing nature of the ecosystems to which we belong.

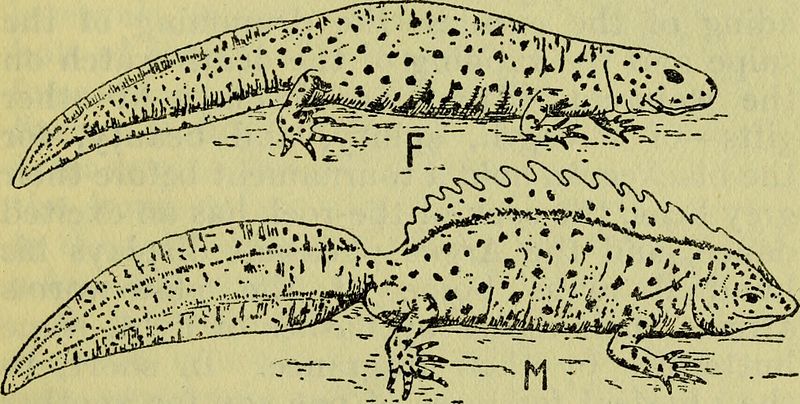

Reactive Sexing

Across manufactured landscapes, and through chemically polluted oceans, endocrine disruption presents a challenge to how we conceptualize sex. In unravelling the knots in this issue, we turn to a model of sex that emphasizes sex as a dynamic processes in which organisms have more or less “open potentials” of sex, sex-related characteristics, and behavior.M. Ah-King and S. Nylin, “Sex in an Evolutionary Perspective: Just Another Reaction Norm,” Evolutionary Biology 37 (2010), pp. 234–46. Instead of thinking of sex as a nature-given dichotomy, or essentially discrete characteristic, sex is better understood as a responsive potential, changing over an individual’s lifetime, in interaction with environmental factors, as well as over evolutionary time.

Many species have environmental sex determination, in which temperature, pH, or social environment (dominance hierarchies, sex ratio of group, sex of potential partner) influence an individual’s sex, and sex-determination mechanisms have changed between genetic and environmental sex determination multiple times during evolution.J. E. Mank, D. E. Promislow, and J. C. Avise, “Evolution of Alternative Sex-determining Mechanisms in Teleost Fishes,” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 87 (2006), pp. 83–93; Ah-King and Nylin, “Sex in an Evolutionary Perspective.” Furthermore, there are many species that sex change regularly as part of their life histories, such as shrimps, ringed worms, echinoderms, mollusks, and some fish.P. L. Munday, P. M. Buston, and R. R. Warner, “Diversity and Flexibility of Sex-change Strategies in Animals,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 21 (2006), pp. 89–95. Sex change may be induced at a certain body size or age, or in response to social conditions. The timing of the sex change often appears to be an adaptive response to an individual’s social and ecological environment.Munday et al., “Diversity and Flexibility of Sex-change Strategies in Animals.” Genes for sexual characteristics are carried by both sexes, regulated by hormones, and, therefore, characteristics of both sexes are within the “potential” of most individuals; that is to say that sex changing, intersexuality, and expressing characteristics of both sexes is, for many organisms, part of their species potential.

Potential: to become. Capacity: is directed toward an elsewhere, an unknown future (even if that future is un-becoming). Latin potentialis: from potentia, “power,” from potens, “being able.” Potential is an expressive unit, force, and excitation through which organisms, bodies, and environments become themselves and more. Organisms are creative responses, improvisations with and through their capacity to become with their environments (but always through the refrain of their sensoria—their ability to sense and perceive their environments and those that inhabit it).E. Hayward, “FingeryEyes: Impressions of Cup Corals,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 25, no. 4 (2010), pp. 577–99. Sex potential is just that, an opening out, a responsiveness that is ontologically more dynamic than static. While some organisms have a narrow regular range of sex possibilities—their potential is more delimited—the effects of endocrine disruption provide a reworking of even these limits. In other words, while some species of fish more easily shift from female to male as an environmental response to pollution, other species, such as polar bears, shift with more trouble. And yet, hormonal disruption assures changes across borders of sexes.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Considering that all animal life shares an evolutionary past, many of us also share hormonal vulnerabilities. Hormone levels change over an individual’s lifetime and are affected by lifestyle (stress, physical activity) and exogenous hormones.Roberts, Messengers of Sex. Even natural plant substances like phytoestrogens interact with the endocrine systems of various animals.H. Adlercreutz, “Phyto-oestrogens and cancer,” Lancet Oncology, vol. 3 (2002), pp. 364–73. Our material culture—as expressed by what objects we encircle ourselves with, the food we eat, the water we drink, the hormones we and our food industries gush into our surroundings, the air we breathe, the perfumes, soaps, shampoos, and lotions we use, the ways we use our bodies—all becomes part of the process of sexing. Hence, meshing our discussion of hormone disruption with our ontological view of sex as a dynamic processSee Ah-King’s 2010 article with Nylin, “Sex in an Evolutionary Perspective.” proffers an interpretation of sex that enfolds toxification into the provocations of sexing. In this way, emerging transsex characteristics and “symptoms” can be understood as potentials rather than iterations of sexual difference. In this approach, we resonate with Bailey Kier’s perspective on “shared interdependent transsex,” by which he attends to the ecologically constitutive nature of bodies: he refers to “bodies” as constant processes, relations, adaptations, and metabolisms, engaged in varying degrees of (re)productive and economic relations with multiple other “‘bodies’, substances and things.”B. Kier, Interdependent Ecological Transsex: Notes on Re/production, ‘Transgender’ Fish, and the Management of Populations, Species, and Resources,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 20, no. 3 (2010), pp. 299–319. In alliance with our project here, Kier’s entanglement works to decenter normative assumptions about embodiment, futurity, and nature.

Human sex is responsive rather than recalcitrant to the bumptious forces of bio-industrial-chemical advances. Toxified and polluted, sexual assignments are reshaped and morphological specificity is undone.M. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Durham, BC: Duke University Press, 2012. Sexual differentiations are still at play, but their familiar parameters and orderings become ambiguous and uncanny; alterity between the sexes, however imagined, is unanchored. Already, sexual life as we know it is dissolving in kinds; through the unwilled transformation of toxicity and biochemical materiality, the call-and-response formation of bodies and their relations has redynamized corporeality. In this way, the supremacy bestowed to sexual difference—its ontological forceThe history of medical research on hormones, endocrinology, is permeated by conceptions of natural binomial sex differences and the naturalness of heterosexuality (see N. Oudshoorn, Beyond the Natural Body: An Archaeology of Sex Hormones. New York: Routledge, 1994; A. Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books, 2000; and Roberts, Messengers of Sex). These heteronormative conceptions of the relationships between sex and hormones are carried on in discussions of endocrine disruption today (Roberts, Messengers of Sex). —is outpaced not only by social or political movements but also by metabolizing pollutants, xenotransplanting toxicants, and intravenous banes.

Resilience Potentials

At the start of the twenty-first century, we are swamped globally by endocrine disruptors that unsettle and disarrange environments—the milieus and territories through which species emerge with each other. Species “become with”Donna Haraway in When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008) troubles Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s now famous “becoming animal,” with an attention to the phenomenology of prepositions. Proffering “becoming with,” Haraway brings into focus Deleuze and Guattari’s attention to intensity and multiplicity, while attending to the material conditions of contact, encounter, and immediacy. The preposition “with,” here, is an ethical domain; meetings are built through obligations, indebtedness, and responsibility. Haraway writes, “We are all responsible to and for shaping conditions for multispecies flourishing in the face of terrible histories.” “Becoming with,” then, is a threshold of emergence that attends to ways in which the expressiveness of encounters envelops bodies, exchanging elements and particles of one another such that the members of the involvement become more and different. in principle: become with habitats, resources, associations, and involvements. In this way, endocrine disruption is an unavoidable copresence in the liveliness of organisms. It remains crucial to politically resist the continued leaching, dumping, and producing agents of hormonal disruption, but equally important is to take stock of the conditions of the present. We live within unruly effluvia and wayward discharges that promise to affect sexual, cognitive, and corporeal existence. For now, we are over our heads. The questions are: Can we engender environmental responsibility without invoking anxiety that our most intimate reproductive environments have been infiltrated by an industrial world? How do we begin to think freshly and innovatively about environmentally induced sex and body changes without reinscribing gendered biases, sexual fears, and old prejudices?

How can we discuss the effects of endocrine disruptors seriously, without retelling heteronormative understandings of sexed biologies?

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

As M. Ah-King and S. Nylin demonstrate, seeing sex as a reaction norm, a potential, opens up new ways of perceiving environmental sex change as a part of a developmental process, whether it occurs in species that regularly sex change or don’t.Ah-King and Nylin, “Sex in an Evolutionary Perspective.” That hormones are a part of our sexing process throughout life means that there is potential for arbitration and regeneration. There is no need for sex panics. Seeing sexing as an ongoing process also means that there is potential for healing and restoring. Some stages in organismal development are more vulnerable than others; some incur nonreversible changes in the physiology. Others are short-term and reversible. We know that the endocrine-disrupting substances in plastic softeners are discharged from the body relatively quickly, while substances like DDT and PCB may be stored in fat tissue for decades. The DES prescribed to pregnant mothers still affects descendants after three generations. Temporality, here, is part of organisms’ sex potentials. That is to say, sex is longitudinal and ongoing; time (within a toxic context) is part of sexing, part of its unfolding (potential) nature.

Reinvigorating the promise of transgender and queer politics, sexual difference, an engine of difference, is wrenched and retooled by toxicity and pollution, propagating variability rather than difference as usual. Neither utopic nor dystopic, toxic sex opens the realization that bodies are lively and rejoinders to environments and changing ecosystems, even when those same engines of change provide exposure to carcinogens, neurotoxins, asthmagens, and mutagens.

"Seeing the beauty in the wounds and taking responsibility to care for the world as it is” is what we aim for here.C. Mortimer-Sandilands, “Unnatural Passions? Notes towards a Queer Ecology," Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, vol. 9 (2005), http://hdl.handle.net/1802/3756.

We—human and nonhuman—are living in a time of intensified exposure to toxicity where life requires reinvention (if it can) or risks extinction and disease. Things can get worse, and probably will, but life is already dire for many. We are entwined through our descent (and, possibly, our extinction), but also through our coexistence in shared environments. Nonhumans and humans are vulnerable, but also exuberant, adaptable, resilient, and constantly changing in interaction with environments. We are living in environmental catastrophe. Certainly some organisms will survive; perhaps only humans will not.

In an effort to critique the medial focus on threats to “natural” and normative sex and sexuality, this essay proffers a critical perspective for understanding environmentally induced sex changes, and encourages a counter-discourse that rethinks our purity and “chemical free” ideas so as to simultaneously comprehend threat, resilience, and potential. Embodiment, which includes sex, is a process of becoming with these altered environments. Whatever futures await us, we are the future organisms that we are becoming.

This essay is a shortened and slightly edited version of the original essay, published in O-Zone: A Journal of Object-Oriented Studies, Issue 1: Object/Ecology (2013).