Detail from tarot card "The Lovers", the Rider-Waite tarot deck

Pamela Coleman Smith, 1909

The Byzantine Generalization Problem: Subtle Strategy in the Context of Blockchain Governance

Who is responsible for making the decision on how to make decisions? Researcher Kei Kreutler analyzes the decentralized, consensus-driven decision processes implemented in blockchain technologies from a more general perspective of governance. Such an approach allows for a more nuanced negotiation of agency, power, and stakes in decision processes for both technical and social organization.

One neuroatypical Roman emperor-to-be had a steep onboarding process for his court astrologer. Tiberius Julius Caesar would walk prospective astrologers along the coastline, drawing out their forecasts for pivotal events: a river flooding, a coup on the current emperor. As they wound their way to the highest cliff, he would ask them to look upon their own astrological birth chart and foresee their death, only to be thrown into the rocks below moments later.

It wasn’t until the astrologer Thrasyllus—who would go on to successfully predict the current emperor’s ousting and the rise of Tiberius—looked up from his own chart to say, “It looks like I’m in grave danger right now,” that he filled the court position.

While we look back condescendingly on the centuries when stars acted as movable spokes for power, the credibility we attribute to our own maps of the future may stand on equally influenced ground.

Skin in Whose Game

It is my estimate that approximately 2,321 blockchain whitepapers contain the phrase “skin in the game.” Repopularized by Nicholas Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan and the chaos cults’ preemptive answer to Jordan B. Peterson, the phrase signifies the degree of personal risk someone assumes in a given situation. Put your money where your mouth is; make it or break it; or, when signifying prediction markets today, vote values but bet beliefs. While the phrase can have many interpretations, it can be one way to divide the opportunists from the invested, those who stand behind the opinions they espouse. In Taleb’s conception, within the bounds of the “game,” those who stand with nothing to lose act for social signaling—positioning themselves loudly while committing nothing.

In the story of Tiberius and Thrasyllus, the emperor-to-be put the astrologer’s life at risk, but the question of the astrologer’s agency remains. Did the emperor’s reputation precede him, and the story of the other would-be astrologers travel, or did the astrologer enter into the risky situation unaware and without other options? As in Thrasyllus the astrologer’s case, the majority position of a power asymmetry between an individual and their environment, or an individual and an institution, means an individual’s stake is primarily defined externally. The intermediating, or more powerfully leveraged, actor is more capable of setting the terms and risks of engagement.

Blockchain technology claims to be trustless, in the sense that individuals don’t have to trust intermediaries or more powerful single actors in order to act and interact. The technical system off-loads authority onto a transparent and public consensus history, created and validated by the protocol and some of its users. The technical system could be considered a “trustless,” multiauthored actor in its own right, with the however unlikely and expensive scenario of its own validators’ collusion. “We don’t need to trust each other before we can begin to collaborate,” blockchain technology claims. Through the massively poor media reporting on blockchain, this claim can come to be misinterpreted, as today’s dominant connotation of trust suggests something interpersonal and chosen. The term “trustless” skims over that what may have been previously defined as “trust”—as in trusted institutions—and in many scenarios may not refer to voluntary, cultivated relationships but instead arise as a result of contingency and lack of alternatives. In this light, trust was the network effect of rumors around consolidation of power.

Enter a replicated state machine, or by another name, a blockchain. By producing consensus history through cryptography and computational power, tokenized blockchain applications can allow individuals to define the degree of their own stake, their own investment and risk. They can also rewrite the boundaries of the game, so that those who are unwilling or perhaps unable to evidence stake, “skin in the game,” cannot play at all.

Pregame Theory

The Bitcoin whitepaper claimed blockchain to be a general solution for Byzantine fault tolerance in computer science, which takes its name from the game theoretical Byzantine Generals’ Problem.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

a

The Byzantine Generals’ Problem has to do with agreement. The illustrative story tells of a group of commanding generals who encircle a city and have to formulate an attack plan. There are two options: attack or retreat, and the generals need to come to a consensus decision in order to make the plan effective. Further complicating matters, having surrounded the city, the generals are geographically distant from one another and to communicate their decision to the others, they have to rely on a messenger. A messenger who might take the fastest route through the city center to the other side might be efficient, but there would be no way of knowing if their message had been tampered with: Were they bribed at the gate? What if the messenger never arrives?

In computer science, “Byzantine fault tolerance” describes the dependability of a system to reach accurate consensus with potentially unreliable actors. The Bitcoin blockchain addresses this issue by assuming that the computational power required from a malicious actor to attack the network would be too great and too expensive to be able to override the other actors on the network.

The design of incentives becomes integral to consensus-driven technical systems, which aim to coordinate many actors at scale and navigate a slew of game theoretical problems. Illustrated by the cross-wired motivations in the case of the Prisoner’s Dilemma or the Tragedy of the Commons, coordination and cooperation relies on aligning as much as possible the best interest of an individual or organization with the others involved. So, incentive design can be seen as mechanistically hedging against organizational stalemates or failures.

Rather than seeing technical, incentivized solutions to social problems, we could alternatively read governance issues as archetypal—mutable and immutable, recurring, and taking intractable forms.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

These recurring patterns are typically mitigated by governance. According to the power law editor crowd of Wikipedia, the definition of governance is “the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented).”UNESCAP, 2009. "What is Good Governance." (https://www.unescap.org/resources/what-good-governance) This definition, however, leaves out a critical first-mover question: How do you make—or more pointedly, who makes—the first decision about the decision-making process without one already in place?

While a paradoxical problem on paper, each day “first decisions” are made at differing scales. Whether it’s sweeping gestures or incremental everyday actions, the ability to establish a new foundational process for how decisions are made and how action is undertaken structurally determines the course of a society, government, or organization. The tyranny of structurelessness—a poorly lit space filled with vague cultural norms and technical limitations but still anything other than empty—is the space from which explicit governance always emerges and into which it sometimes returns.

Blockchain Incentivizes Time Travel

In the current debate around decentralized platforms, the question, Who is responsible for making the decision on how to make decisions?, comes into focus.

In a post from November 2017, Fred Ehrsam, co-founder of Coinbase, claimed, “governance is the most vital problem in the [blockchain] space.” Like organisms, he says, the most resilient blockchains will be those that can adapt to their environment—through implementing adequate governance processes. He details approaches to on-chain governance, which can be summarized as a blockchain having a decision-making system implemented in code. The various approaches include voting, whereby possessing one token will allow you one vote, or having a fully verified identity on your account will allow you one vote, a half-verified identity a half-vote, and so on. He goes on to mention futarchy and forking. Voting on-chain could encompass issues such as protocol updates—new features and security fixes—and changes in governance processes and community stakeholders.

On-chain Governance

1 “Person” = 1 Vote

Problem: You can create infinite accounts.

1 Token = 1 Vote

Problem: You get plutarchy.

1 Verified Identity = 1 Vote

1 50% Verified Identity = 0.5 Vote

1 Anonymous “Identity” = 0.25 Vote

Question: Do we want verified blockchain identities?

Two weeks later, Vlad Zamfir countered with “Against on-chain governance,” arguing governance is a complex social process that shouldn’t be fully technically encoded, and, perhaps more importantly, that those parachuting into the governance debate to propose solutions with far-reaching impact undermine the development and community work that has come before, potentially disenfranchising other actors not accounted for in a social or voting-based governance system. Whether it’s Ethereum’s the DAO or Bitcoin’s SegWit2x deliberations and New York Agreement, so far there have been discussions and lengthy deliberations around blockchain governance, on how to counter changes in the protocol and on how to technically travel back in block-time to before a hack, and while processes like the submission of Ethereum Improvement Protocols (EIP) are themselves improving, it might be beneficial that more governance standards have yet to be set in stone for developing technology that needs room to iteratively fail and succeed. The only issue with this, then, is if in the meantime someone can come in to make the first decision about how decisions are made, leaving all other choices absurdly empty.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The Byzantine Generalization Problem

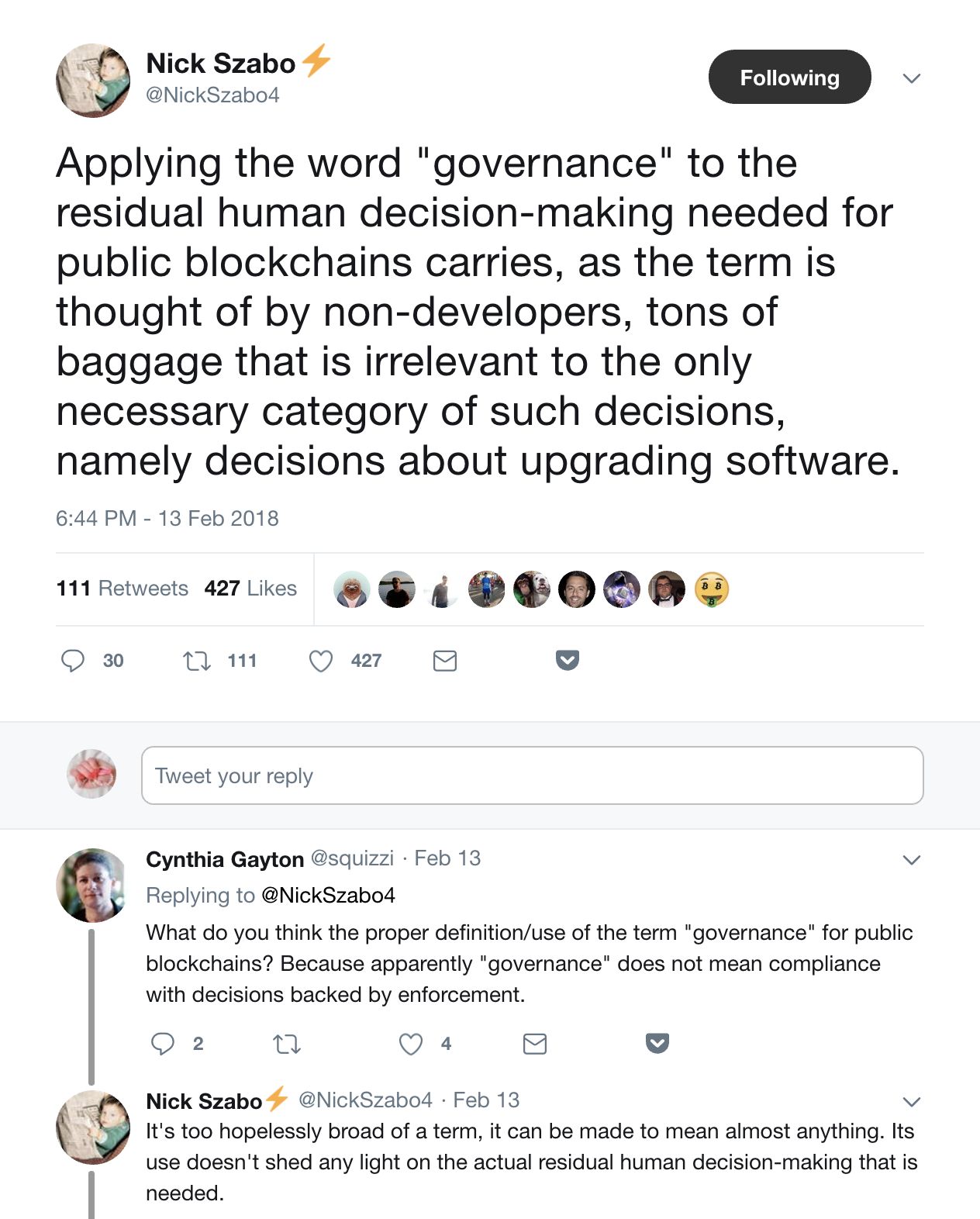

Nick Szabo, who happens to be the originator of the term “smart contracts” and the second likeliest suspect behind the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, wrote:

large

align-left

align-right

delete

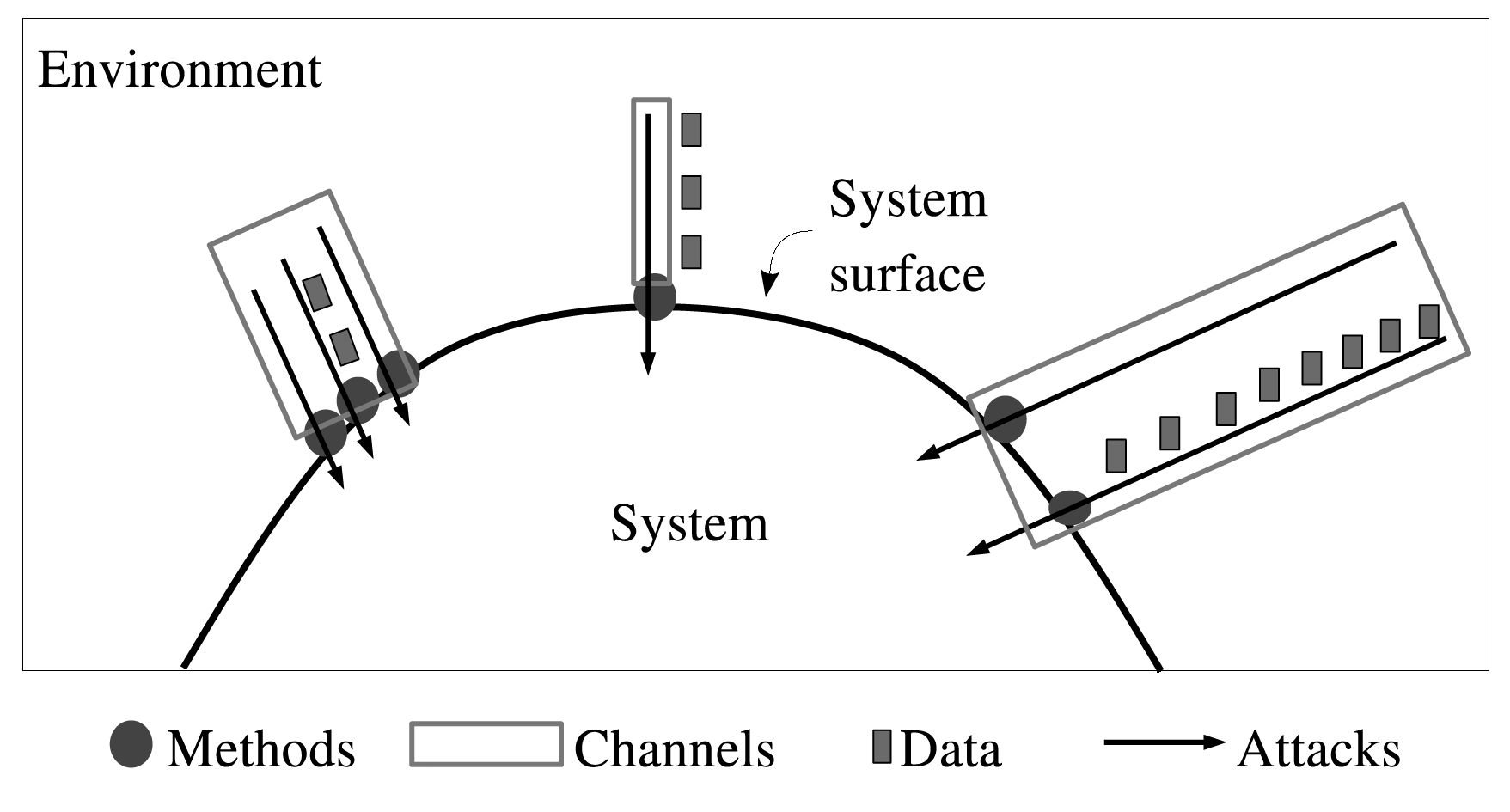

While the arguments around governance abound, the question of what’s at stake in the discussion remains hazy. Depending on who you ask, it’s anything from the future of all asset exchange or organizational design to simply the fates of a small group of developers and a few entangled bystanders arguing over software updates. Either way, “governance” and “game theory” are terms that can be easily deployed to obfuscate a task at hand. In computer security, there’s a concept of “attack surface,” the total possible attack vectors in a technical system—that is, hackable entrance points for data entry and extraction. It’s best practice to keep the attack surface as small as possible. A simple metaphor would be how many doors with faulty locks one house has.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Szabo writes that where in security there is an attack surface, in questions of governance, there is an “argument surface”: the total optionality in a given system or organization. That is, each next step or action that can be enacted in more than one way opens the space for deliberation and argumentation, and, well, perhaps it would be better to limit the argument surface, too, by off-loading as much as we can to a technical system, in order to keep acting. For example, if the amount of transactions processed in every “block” had to be decided by the community, it would open a vast possibility for argument and contention. Instead, what is referred to as the “block size” is technically predetermined by the protocol.

While there’s significant overlap between game theoretical problems in computer science and human organization, distinctions remain. As a governance mechanism, consensus is defined as unanimous agreement, or at least no remaining challenges to an agreement. Matan Field, from DAOStack, delineates between “objective consensus,” required by a technical system to be in agreement about the order of previous actions and its current state, and “subjective consensus,” the only semi-explicit charted terrain, which is the argument surface through which humans deliberate and make decisions.https://epicenter.tv/episode/237/ Subjective consensus is rooted in conversation: making an argument for the best way forward and debating any alternatives.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

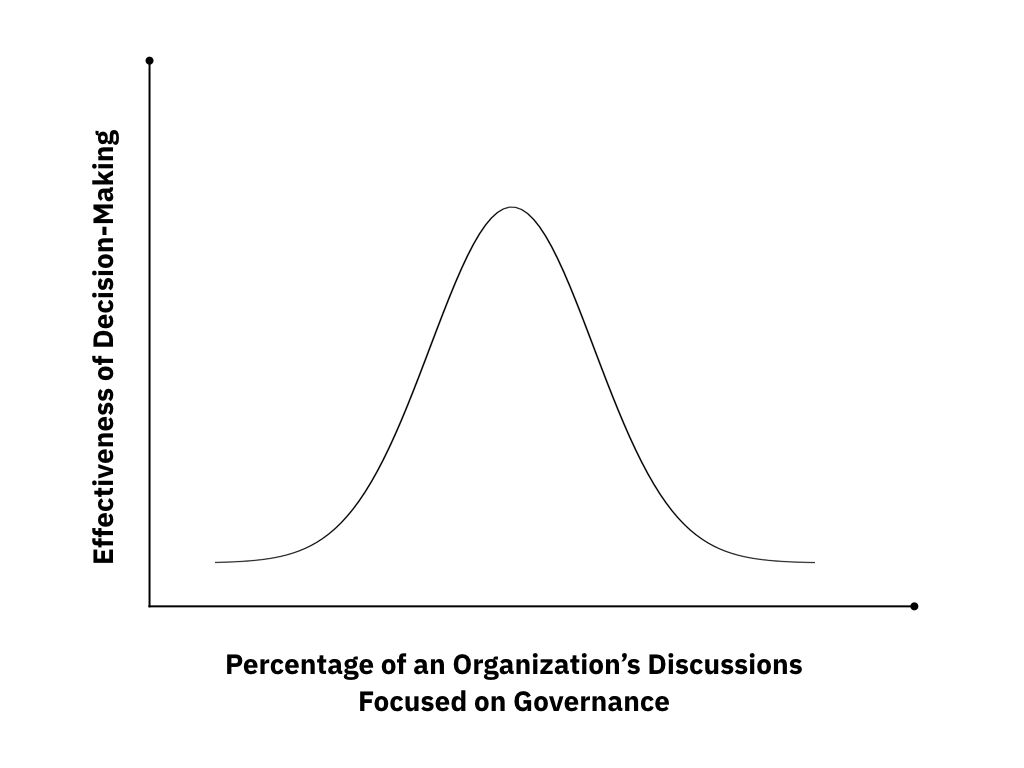

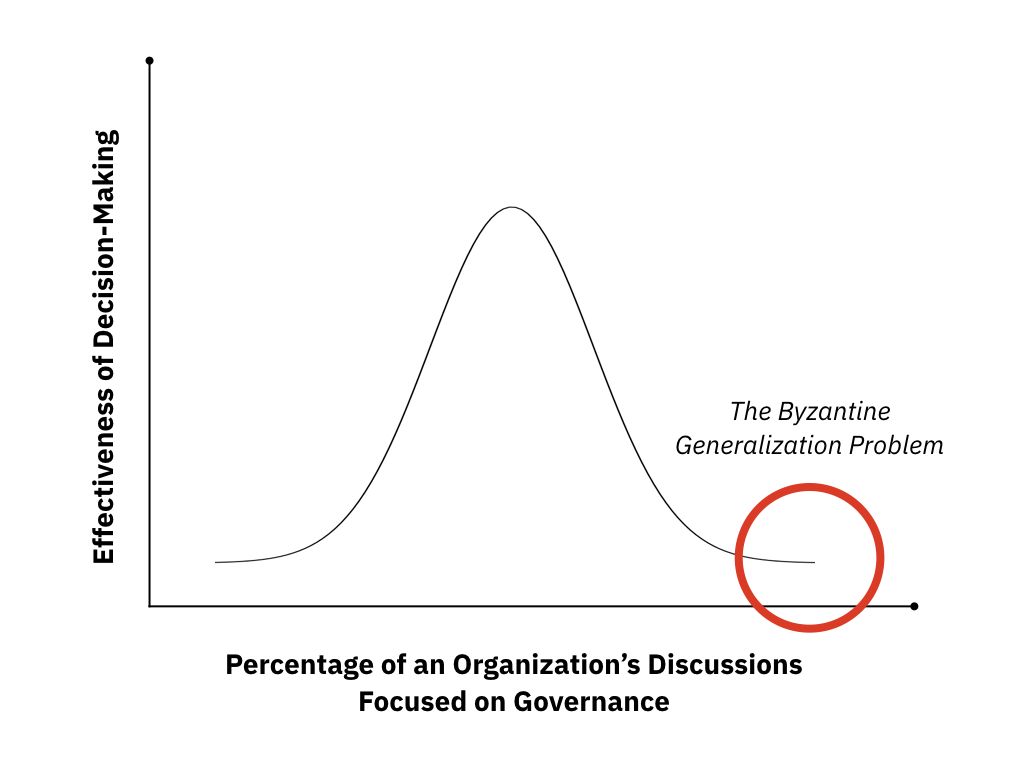

There is, however, something like a third way: an inexact science for navigating the Tower as tragedy of the commons, as the community-owned resources lie misused all around you, while the assembly meeting goes two hours over schedule. The importance of what Szabo highlights in any governance framework’s “argument surface” is something evidenced by the backlash against Ehrsam’s post calling for urgent action on blockchain governance: who can claim the ability to make the first decisions and who can continue to custom frame the governance issues. While perhaps lack of governance has seen the radical politics of early Bitcoin become stalemated into creating privately distributed ledgers for improving banks’ paperwork, there is a tendency of governance creep in any fledgling organization or stewarded resource, in which the frequency of discussions on governance processes has an oddly distinct relationship to the effectiveness of putting said governance in place and avoiding external capture.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

When all basic decisions start becoming decisions of governance, when all questions are questions of agency to make a decision, a curious epiphenomenon occurs. It’s here that totalizing jurisdiction approaches the asymptote of impossibility of action.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The Byzantine Generalization Problem describes when all issues in an organization or technical system are framed as governance issues. Any question that’s brought before an organization can become a question of who has the agency to provide the solution. Even if it’s fixing the broken plumbing in a housing co-op, when framed as a governance issue, the debate on who should take care of it could last for weeks as the pipes leak and the toilets fail to drain. The generalization of governance can be applied to every challenge an organization faces, especially when there is no clear—or technically embedded—solution at hand. When the complexity of the organization grows, this “generalization problem” applies exponentially, with considerably less clarity on the necessity of action than in the example above.

A DDoS attack on governance, the Byzantine Generalization Problem is the opposite means to the same end of the tyranny of structurelessness. In consensus culture, often the most indefatigable wins, and power is implicitly consolidated by those who provoke interrogations of process. Perhaps a social formula lurks that can be translated fully into equation—the seat atop the precious bell curve in the pseudo-chart above—that would lead to transparency, clarity, and appropriate calibration of deliberation on governance systems. Everyone has their opinions on how to solve it regardless, ad nauseam and ad infinitum.

That said, as we learn from programs that sponsored the use of consensus, the Byzantine Generalization Problem can be used as a strategy to delay decision-making when necessary and to tactically, obliquely question the right to power. Ambiguous, unattended responsibilities are the “attack surface” and way in.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Another strategy could be to start with a given end goal and seek to map the context and required actions for it to be reached. Such a theory of change relies on an adequate mental model of the environment—with the corollary that the greater the complexity of the environment, the more obfuscated its model’s underlying assumptions are—and importantly, it relies on formulating a multiplicity of understandings of how change may occur in the environment. While governance, incentives, and protocols may be the most explicit frameworks to guide organizational action, there are always other tools available and already at play.

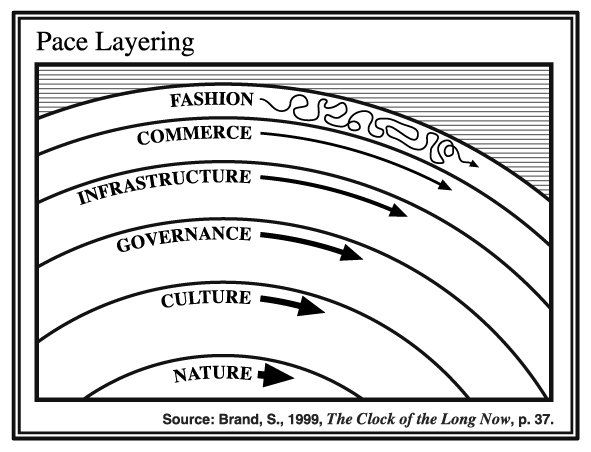

A theory of change can metabolize its environment through time and narrative, incorporating strategies with ulterior rhythms and cloaked intentions. The most efficient path from A to B may be the most hidden and illogical one, based on learning acquired from missteps and faulty data. In the pace-laying diagram above, we can conceive of the different rhythms of change—from the slow yet impactful arc of culture and the informative flippancy of fashion—and formulate narrative strategies and technical impositions intersecting with each.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

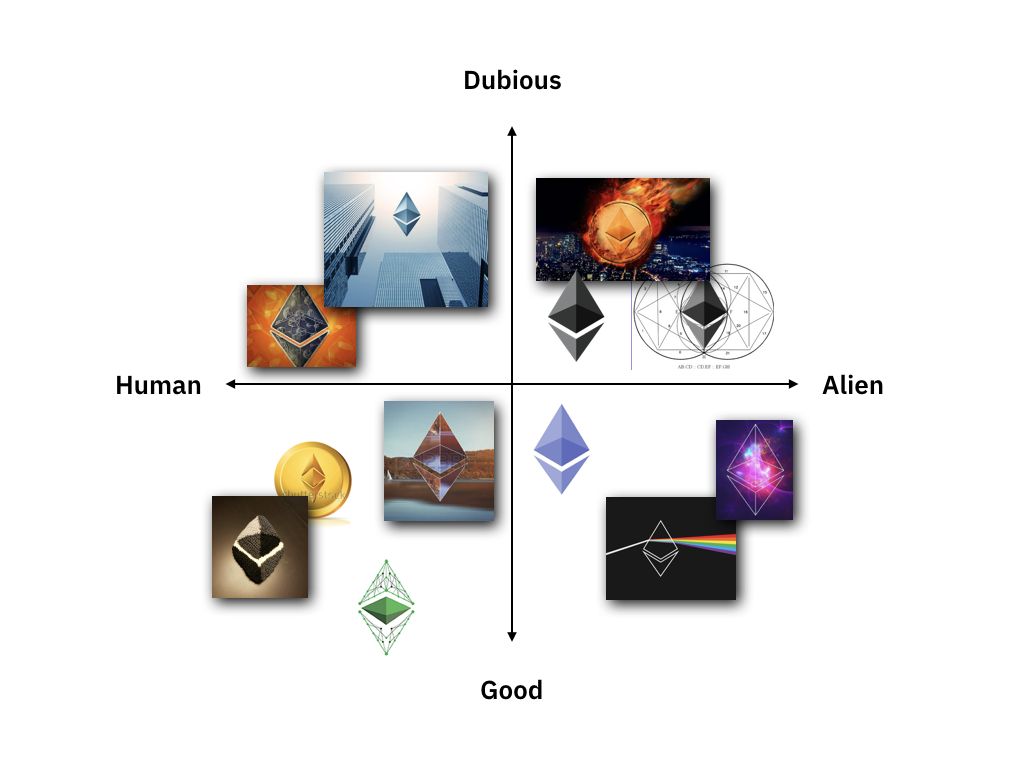

Aesthetic narratives and false juxtapositions propel change equally as, if not more than, governance protocols do. Every narrative can be framed in every light. Ethereum, a blockchain platform and protocol that launched in 2015, has seen its own innumerable iterations and adaptations since. Each Ethereum logo has its own part to play, or something. Trusted governance and authenticity must be considered a question not solely of explicit or defined processes but also of subtler forms of manipulation.

It’s become critical to realize that there has always been fake news, and moreover, that exposing the most accurate information will not in any way necessitate it being acted upon. Fake news—what previous generations may have confined to an understanding of propaganda—is the inevitable result of both massive media industries and small-scale social gossip that travels from one town to the next. Misinformation often comes in gradients, and its propulsion can be as similarly effective as diverse aesthetic and implicit narratives. The Truth is always preceded by a bounty on its name.

Each time you point a finger at falsity without offering a significant, desirable counter narrative, politically or aesthetically, you grant the central authority of truth-making a wider warrant to dismiss all facts.

It is by hyperstitionally navigating ambiguity, taking into account the tools unused and the egregores at play, that claims to governance can be made. In the case of blockchain, and of decentralized governance platforms as they become more widespread, surely not all those affected by the outcome of a decision will possess the requisite token to proportionally offer their stake. If you have the first-decision-maker advantage, how do you shift the terms of who's allowed to have skin in the game to be more inclusive of affected parties?

The debate surrounding decentralized governance assumes governance is the main arena for enacting change, but whether it’s the self-owning forest of terra0 or Trent McConaghy’s Nature 2.0, the exponentiating legibility of inhuman and ecological actors’ agency to capital will increasingly transform our understanding of what governance decisions have always been made outside our process-based control. Legibility to capital, however, is not our end goal.

While the Byzantine Generalization Problem escapes exact science, it’s perhaps with a more nuanced understanding of how to leverage governance claims that Thrasyllus’s ability to correctly and adaptively read the conditions of power at stake in his own stars may find its home in the direct action of the future.