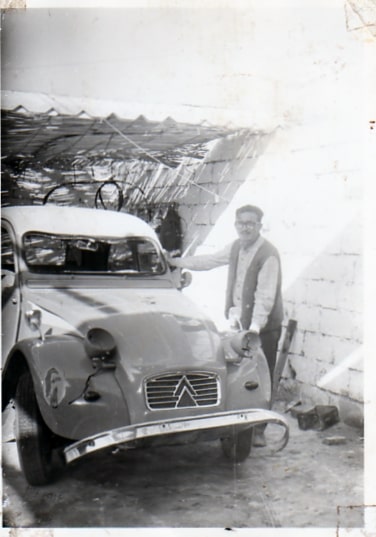

Don Pedro poses with his Citroneta in 1969.

Memories of the Yagán: The Chilean Automobile for the People

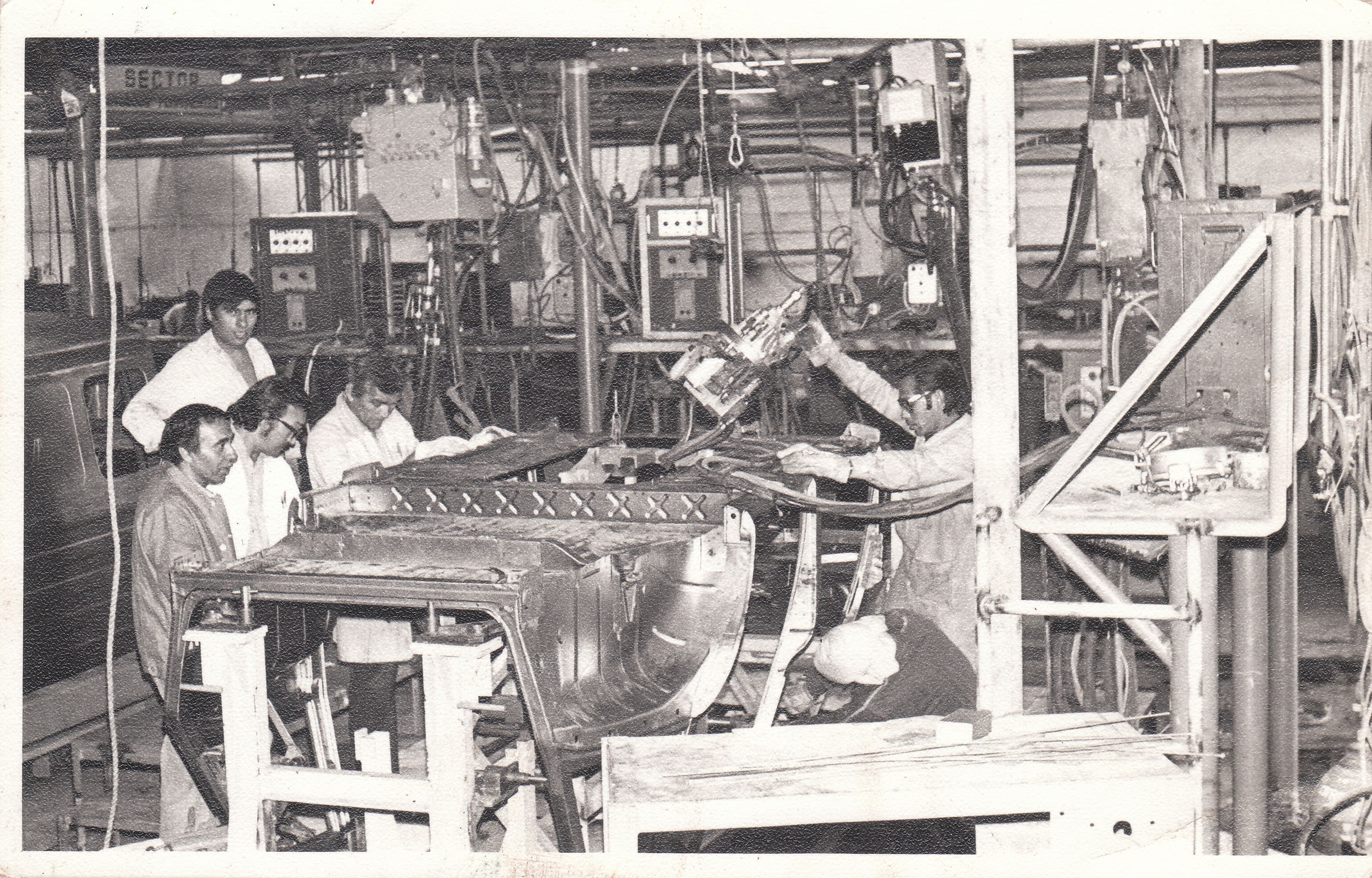

The Yagán, a low-cost utility vehicle placed onto a Citroën chassis, was manufactured by the socialist Chilean government between 1970 and 1973 as part of an effort to provide affordable goods for every citizen. Its story is one of local craft, misdirected politics, and design on-the-fly, which historian of science Eden Medina has carefully framed alongside an interview between her husband, Cristian Medina and his father, Don Pedro, who was in charge of methods for the car’s manufacture.

My father-in-law, Pedro Medina Sotomayor—or Don Pedro, as I call him—fills silences with stories. He’ll talk about his years as a taxi driver or union leader or the time one of the thirty-three miners stopped by his house to visit the miniature replica he built of the Chilean mine that collapsed in 2010. He has no filter when he talks, is never late, loves to tease, and takes pride in doing a job well and on time. He also played a central role in Chile’s short-lived attempt to build an automobile for the people.

Don Pedro worked for the auto-manufacturer Citroën from 1959 to 1985. When the socialist candidate Salvador Allende won the presidential election in 1970, Don Pedro was Director of Methods at Citroën Arica in northern Chile. Allende’s government, Popular Unity, pushed to increase the quantity of low-cost goods for popular consumption. Such policies paralleled those for income redistribution, increased production in the state-run sector of the economy, and decreased unemployment. From 1970 to 1973, the Allende government manufactured low-cost automobiles, motorcycles, sewing machines, household electronics, and furniture. Consumption and production thus formed important and interlocking parts of Chile’s plan for peaceful socialist change.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Following Allende’s election, Pedro Vuskovic, minister of the economy, ordered the manufacture of a utility vehicle akin to the jeep that would cost less than 250 dollars to produce. Using funding and technology from its parent company, Citroën, the Chilean plant where Don Pedro worked drew up plans for a utility vehicle modeled after the Citroën Baby Brousse, a car the French manufacturer had designed for public transport in Vietnam. The Chilean plant also drew inspiration from the Citroën Méhari, a low-cost utility vehicle manufactured in Argentina during the 1960s. The Chileans named the new design “Yagán” in reference to an extinct indigenous people from Tierra del Fuego, Chile’s southern tip. While the chassis, motor, and suspension system for the car were repurposed from other Citroën models, workers in the Citroën Arica plant designed much of its body and tested it for manufacture.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Cristián Lyon, head of Citroën during the Allende era, described building the Yagán as an artisanal undertaking rather than a science: cutting here, straightening there, and creatively combining parts from Citroën vehicles past to produce a distinctively Chilean automobile. “I insist it was almost a metaphor for the history of Chile,” Lyon remarked in an online interview, perhaps referring to the ad hoc willingness of Citroën workers to construct something new from the ground up, regardless of the hurdles involved.Interview of Cristián Lyon, “Creando El Yagán,” 2003, formerly available at the Web site of the Corporación de Television de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

On September 11, 1973, a military coup brought Chile’s socialist experiment to an end. Citroën sold the remaining Yagáns to the Chilean military. There are stories of the military’s dropping the cars from low-flying airplanes to see if they could be used to patrol the arid border between Chile and Peru. The cars did not fare well.

Chile returned to democracy in 1990. Since the late 1990s scholars and journalists have regarded the Yagán as an example of Chilean technology under socialism, and a material representation of Allende’s utopian project that never came to pass. Chilean television, film, and print media all have named the Yagán as an important milestone in Chile’s automotive history, and it was featured as an installation in Chile’s 2010 Design Biennale as representative of the event’s theme “Chile se diseña” (Chile Designs Itself). The 2003 documentary La Huella del Yagán (Tread of the Yagán) portrayed the car as an object of nostalgia. It filmed the journey of two young Chileans as they drove a Yagán from Santiago to the northern city of Arica, where the car was manufactured, bringing the historic vehicle back to its birthplace while recounting its origin story.Directed by Patricio Díaz and Enrique León, La Huella del Yagán, Santiago, Duoc UC, 2003 (https://vimeo.com/101574882). The history of the Yagán thus parallels the ruptures and reconciliations of Chilean history, moving from an automobile for the people to a military transport vehicle to a way to remember, understand, and interpret the Allende period.

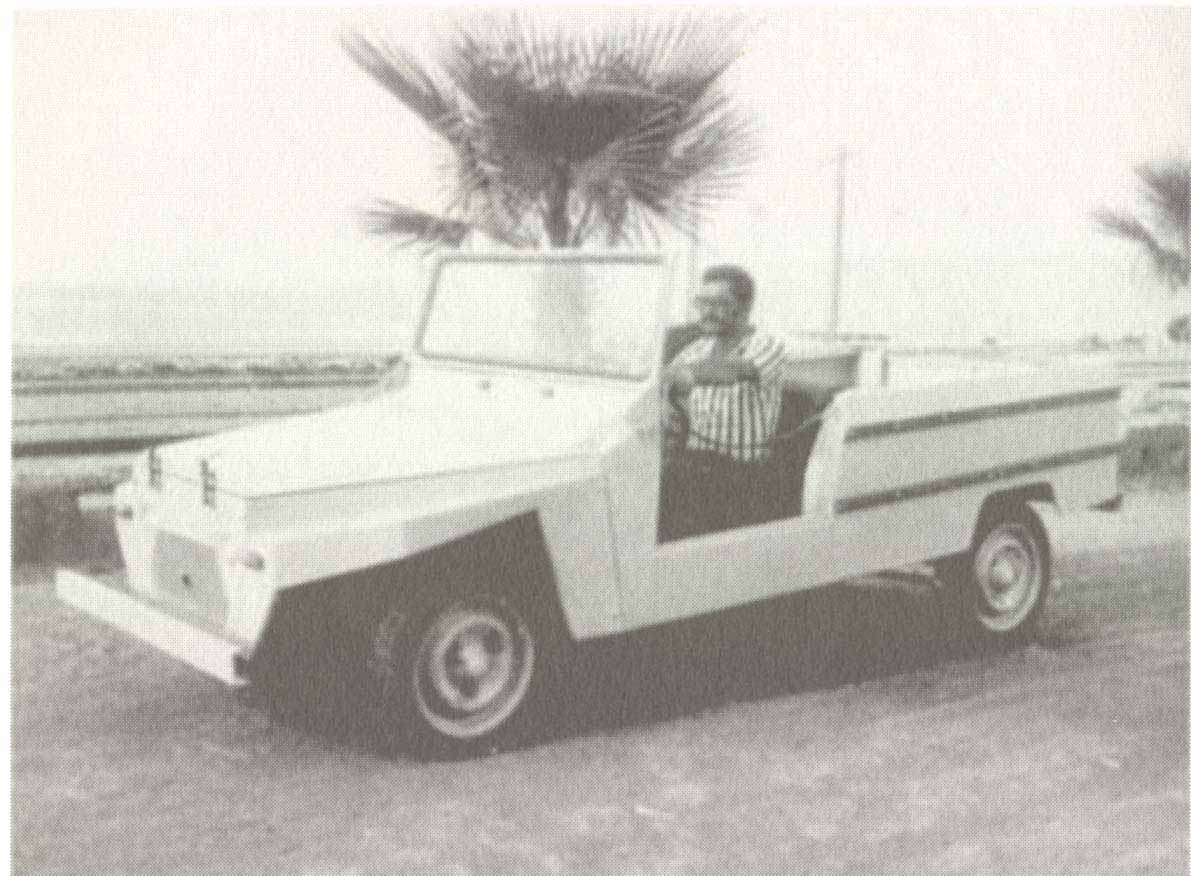

The iconic photograph of the Yagán shows Don Pedro sitting in the driver’s seat; in the background are the beach and palm trees of Arica—the city of “eternal spring.” The photo has brought him in contact with filmmakers, journalists, historians, and automobile aficionados. He is a celebrity in the Citroën Yagán Facebook group.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In 2004, I asked my husband, Cristian, to interview his father about the experience of working on the Yagán project, which I recorded and had transcribed. The resulting transcript is a family history as well as a history of technology. It illustrates how the ideas of the Popular Unity government were carried out on the ground and the daily acts of ingenuity and inventiveness that they required. Technologies become repurposed through acts of repair, reuse, and use in new contexts. However, they also take on new life in our memories of them and the stories we tell of their significance. As we care for, tend to, and retell these technology stories, they become part of the narratives about nations and families and part of how we come to understand them. I have translated and edited an excerpt from Don Pedro’s comments for publication.

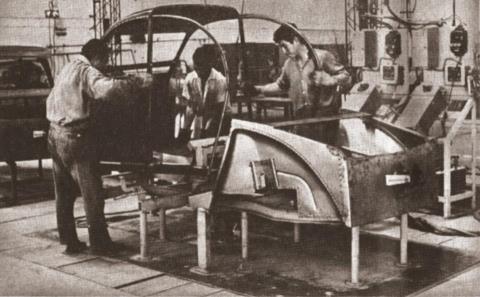

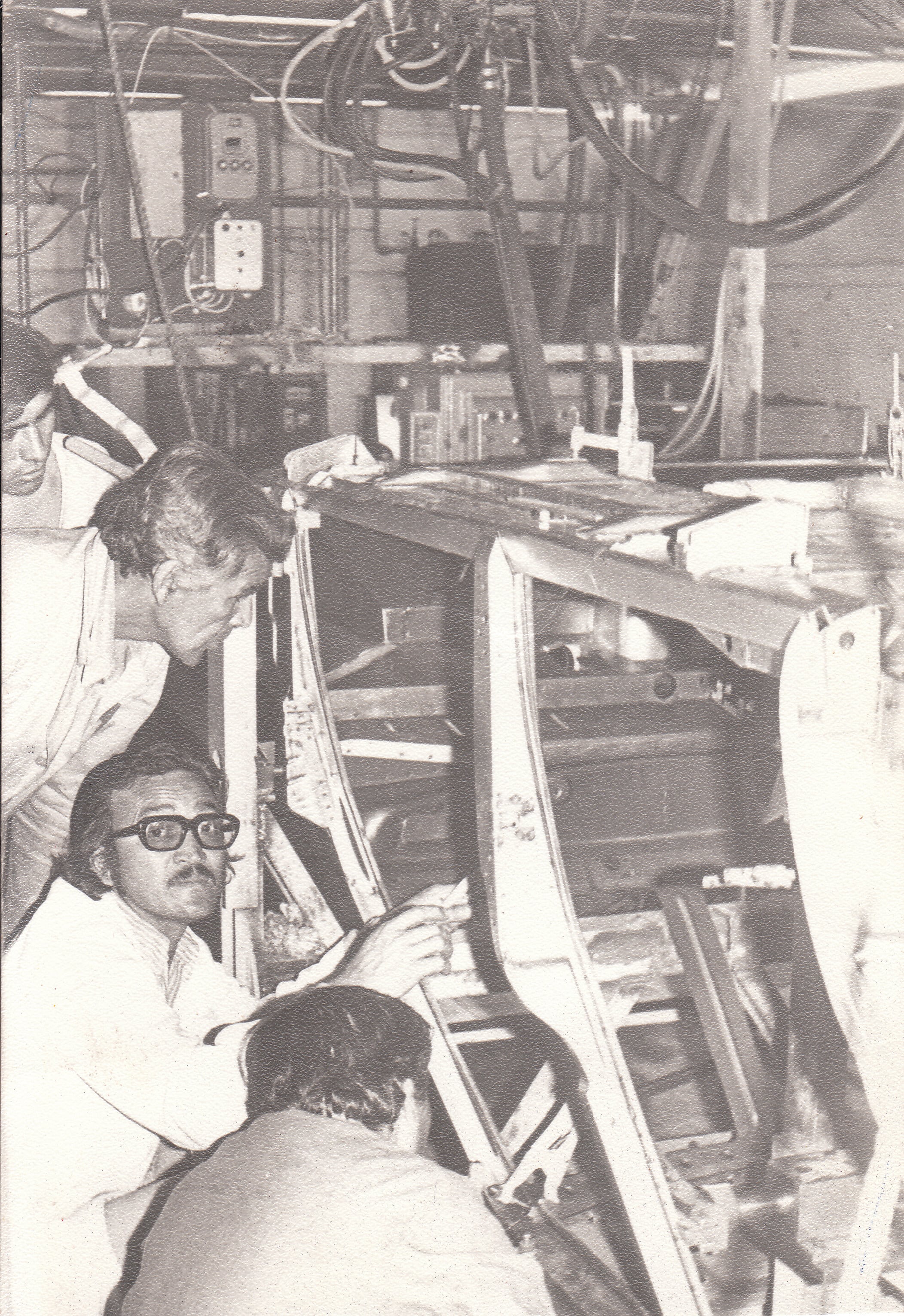

Don Pedro: At the end of 1970, we received an order from CORFO Citroën to make a vehicle like a jeep, a utility vehicle that was easy to make and economical, and it had to be similar to the vehicle that was made in Argentina, the Citroën Méhari.A portion of Citroën’s Chilean operation belonged to CORFO, the Chilean State Development Corporation. That vehicle was compact and all one piece. The bumpers, fender, everything was mounted on top of the Citroneta chassis. I was in charge of the Department of Automobile Methods, which meant I was in charge of some of the methods’ technicians in the car body section, the painting section, and the assembly section. We advised the heads of those sections on the technical aspects of their operations, giving them the timing and operating ranges, everything involved in the technical part of building the vehicle. We made a department of prototypes to make the Yagán, and we made a prototype workshop in a closed-off part of the factory that was directed by Mr. Leonel Segovia. But we oversaw everything. They were making the parts and the pieces, and we asked them to make the blueprints. We were also advising on the technical part, which machine to use—if a fender, which machine would fold it; if it were cut, how to cut it. We made a template for the perforations and decided how to get the most out of the material. We did all of this and sent the information to an archive that contained all these kinds of things, the length and width of the door chains, how the pieces fit together, and that’s how we did it. Now the head of the prototype workshop, Leonel Segovia, had been the head of car bodies at Citroën in 1957 and had a lot of experience and knowledge. He went looking for parts and pieces from a Citroën van that we had made, the AK-6. To avoid making new pieces, we went looking for some that we could use from the van in the Yagán. It allowed us to save time, work, studies, blueprints, and everything else involved.

Cristian: In what way did the Yagán reflect the political context of the Popular Unity government?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Don Pedro: Mr. Pedro Vuskovic, who was the treasury secretary, told Citroën via CORFO that we should make a vehicle, a vehicle for the masses. Because it turns out that the country was in [the midst of] a process of the Popular Unity, a revolution. The new government said, “Let’s make all of this popular, for the masses.” They made the agrarian reform on one hand; on the other hand, they said, “Let’s give the people an accessible vehicle. Cheaper.”

Cristian: And were the cars cheaper to make?

Don Pedro: They were more expensive, because the work was artisanal, by hand. We were not prepared to develop a vehicle. To assemble, yes, but assembling doesn’t cost anything, just the parts and pieces. But to create new things, when you have to deal with material-strength tests, with machines and instruments that measure vibration and fractures; it turns out that we had to improve those issues, the Chilean way.

Cristian: You didn’t have records of stress distribution?

Don Pedro: There were no records of stress distribution. In fact, when we tested the first prototypes, the rear of the vehicle made a lot of noise because the body was loose – it was the body of the van, but the top part was missing. So, we said, “How do we remove the noise? Let’s add wooden slats to the side to reinforce it.” But that was during the building process; it was not programmed in advance. We had to send them to make three slats per side, pierced with three-sixteenths of an inch screws to reinforce the sides and give them rigidity. But those fixes were tailor made. There were no studies.

Cristian: You were not prepared, but you didn’t say that. You faced the challenge.

Don Pedro: And with pride. Yes, we can do it.

Cristian: How was the Yagán different from the previous cars made at Citroën Arica?

Don Pedro: The manufacturer was Citroën Arica, but the cars came with the rules that were established by Citroën France. We had a French quality control system so as not to lose the prestige of Citroën. But we didn’t have a quality control system for the body of the Yagán. We were making quality control procedures on the fly. Our quality control people began to make operational procedures to measure from this point to this point, to make sure the angles were consistent. They were creating these new procedures for the body as we made the vehicle. The engine of the Yagán was the same [as the Citroneta’s], the same chassis, the same gearbox, the same suspension—everything; the only different thing was the body. It was all square and made by hand. Everything was done with press brakes [a tool that bends sheet metal].

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Cristian: Is that the reason the car was so angular?

Don Pedro: Sure, to give it a certain amount of resistance. But it meant that no two [vehicles] were the same. It was all by measurement. I want to make a hood, I measure from that point to that point, and we folded it at such an angle and did the same on the other side. But now, it is no longer the same angle, and the angle is ten degrees more or five degrees less.

Cristian: Did the Yagáns sell? Did you sell them all?

Don Pedro: No, people preferred the Citroneta. Very few Yagáns were sold; we only made about four hundred to five hundred vehicles. But the Yagán got us into trouble because it slowed the whole production process. We were summoned several times with complaints of, “Hey, the fender won’t assemble right,” or “The windshield doesn’t fit.” We made modifications and the whole system fell behind. We put everything on the same assembly line. We put together vans, Citronetas, everything, on the same line. To make a Citroneta we needed 800 minutes; to make a Yagán we needed 1,200 minutes, meaning more men, more people, more time, so it is more expensive.

Cristian: Describe the Yagán, how was it to drive one?

Don Pedro: Well, in those years, you were young, and you felt free [because it was a convertible]. But it was ugly. Ugly. Instead of closing a door, you hooked a chain. It was square, ugly. Mechanically, the suspension had no problems. It was the look of the car body that was ugly. It was aesthetically ugly. Most people who bought one modified the car body. They put on a roof, a back window, doors that also looked ugly and square, but were modifications that made the car safer.

Cristian: What was that anecdote you told me about a gentleman who was driving his Yagán and stopped at a street corner—?

Don Pedro: And the university students shouted, “Hey, your craft project looks nice.” [laughs] To me, even though I was involved in the project from the beginning, it was a failure. It was not useful. They called it a jeep, but we put it in the sand, and nothing. It was just like the Citroneta but with a jeep shell. It was for driving in the city, that was all. In that sense, it was a failure for Citroën. They didn’t sell. The cars were later sold to the army. The army wanted to use them for soldiers who were couriers, the soldiers who go from one regiment to another carrying documents and mail. They used the cars to perform military exercises and gave us machine guns to put on them.

Cristian: Are you saying that this happened later, after the military coup?

Don Pedro: After the coup, they put a machine gun on top of the car for routine street patrolling. The Yagán was a jeep that was cheap, economical, and two soldiers could be seated in the back, two in the front. They had us put in a tripod with a machine gun, the supports and everything. We put it behind the driver’s seat. When the production of the Yagán stopped in 1974, we had a lot of material left.

Cristian: I remember our fence at home was made of—

Don Pedro: It was made of bumpers. Since they weren’t being used for anything, we made fences from them. I remember I made a shed at Citroën and, with the guys from maintenance, put together the joints, the little 1.5-meter-long pieces so we would not waste any material.

In 1982, Chile suffered its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression as a result of the neoliberal economic policies put in place by the Pinochet dictatorship. Citroën transferred Don Pedro from Arica to Santiago, the capital city, in 1983. He lost his job two years later and then found work as a taxi driver. In the mid-1990s, Cristian returned to Arica and took a photo of his childhood home. The house still had the fence made of Yagán bumpers.

large

align-left

align-right

delete