4. Islands. Colonialism and Geopolitics

Understanding Australia’s phosphate mining history on Banaba puts into context its current controversial relationship with Nauru and Christmas Island (in the Indian Ocean) as refugee detention centers, so critical to the bipartisan Australian policy of stopping asylum seekers who come by sea at all costs.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

To Ruin

The Australian government, Australian investors, Australian mining company employees and their families, Australian fertilizer manufacturers and Australian farmers were many of the key stakeholders and beneficiaries of phosphate mining in the Pacific.See the papers of the British Phosphate Commissioners in CA244, National Archives of Australia, Papers of Maslyn Williams, MS 3936, 1850–1995, National Library of Australia; Henry Evans Maude and Honor Courtney Maude Papers and the archival film A Visit to Ocean Island and Nauru 1951–1973; Alec B. Costin and Colin H. Williams, Phosphorus in Australia. Understanding Australia’s phosphate mining history puts into context its current controversial relationship with Nauru and Christmas Island (in the Indian Ocean) as refugee detention centers, so critical to the bipartisan Australian policy of stopping asylum seekers who come by sea at all costs.I am referring to the Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean—an Australian territory formerly mined by the British Phosphate Commissioners—not the Christmas or Kiritimati, Island that is in Kiribati and a wildlife sanctuary.

Nauru, Banaba and Christmas Island are open-cut phosphate mines previously worked by the British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC)—owned conjointly by the Australian, New Zealand and British governments—and operated out of centers in Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland and London.Williams and Macdonald; Macdonald; Katerina Teaiwa, Consuming Ocean Island. The Nauru and Christmas Island detention camps, for example, are situated near old mining fields—Phosphate Hill in the case of Christmas and the phosphate-rich island center, in the case of Nauru.Nauru and Manus detention facilities, while funded and run by Australia, are not listed on the Australian Immigration Department website as they are offshore and subject to Nauruan and Papua New Guinea (PNG), rather than Australian law.

The three islands are deeply sedimented with decades of imperial force. Aside from the evidence in the vast amount of official documentation on the strategic value of phosphate to Australia in the National Archives, the National Library and various state libraries and collections across Australia, both Banabans and Nauruans took Australia to court over the impact of mining on their islands.This extraordinary trip of the High Court was captured in a television documentary produced by Jenny Baraclough, Go Tell It to the Judge (1977), BBC TV, UK.

The Banabans suedSee the positive overview of the work of Pinnacle, the Nauruan Rehabilitation Corporation, funded by Australia, and contrast with an interview with Australian engineer Surawski, "Nauru Rehabilitation Under Threat," Radio Australia, 22 March 2012 the Australian co-owned mining company in a case ending in 1976 that included 206 days of court hearings and a trip of the entire British High Court to Ocean Island. In 1989 Nauru took Australia to the International Court of Justice for underpaying phosphate royalties in the period of mining before independence in 1968. This resulted in an out of court settlement by Australia in 1993 and the establishment of the relatively unsuccessful Nauru Rehabilitation Corporation.

Nauru is now one of the most maligned countries in mainstream and popular media; Alexander Downer describing it in 2008 as the worst place he’d ever had to visit as Foreign Minister. Australia continues to influence the economic and political affairs of its former Pacific territories such as Papua New Guinea and Nauru.

With comparatively larger aid and other assistance packages, it is no coincidence that both countries were persuaded to host Australian refugee detention centers. Australian federal policy has been criticized for lacking compassion for international refugees who come by sea and contravening the UN Refugee Convention that Australia ratified in 1954.See Azadeh Dastyari, "Explainer: Australia’s Obligations under the UN Refugee Convention," The Conversation, 18 July 2013.

Both Nauru and Kiribati still use the Australian dollar as their major currency and both have not been fully rehabilitated as promised over the years by various incarnations of the predominantly Australian-run phosphate mining company.See a useful dialogue on Nauru and Banaba linking these themes, Rearvision: Nauru, with ABC journalist Keri Phillips and guests John Connell, Michael Field, Kevin Boreham and Tess Newton Cain (2 March 2014).

There is a lack of knowledge within the Australian public today of the country’s historical relationship with the central Pacific Islands in spite of widespread media and industry knowledge of the centrality of phosphate mining for Austra- lia’s economic growth for most of the twentieth century.Costin and Williams; Sydney Morning Herald, "Ocean Islanders." Stories of Banaba’s phosphate riches and the concerns of native exploitation abound in iconic Austra- lian newspapers such as the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Barrier Miner, and the Argus. In 1929 Captain Neill Green writing in Life described it as a "Modern Treasure Island":Captain Neill Green, "A Modern Treasure Island," Life, 2 December 1929, 509.

... a small insignificant speck, set in the midst of a vast expanse of water, Banapa [sic], or Ocean Island, as it is generally called, is one of Britain’s most valued possessions of its size in the Pacific. From it approximately 70,000 tons of Phosphate is taken annually.

Like the Australian government’s current "operation sovereign borders" (designed to stop the boats of asylum seekers coming to Australia’s shores) and associated media blackouts, phosphate was a matter of national security with numerous government and defense departments maintaining intelligence and tactical information on the three islands.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

While Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean was uninhabited before mining, the economic, social and environmental impacts on the indigenous peoples and lands of Nauru and Banaba have been devastating, and both communities are today some of the most socially and economically challenged in the region; the Banabans, resettled en masse to Fiji, now a precariously managed minority.

The transformations brought by open-cut mining of small islands are deep and long-term.

The Nauruans, after a period of administration by Australia, gained independence in 1968 and continued to operate the mines. They were temporarily and notoriously wealthy which led to a dramatic transformation of diets, widespread obesity and diabetes. It also led to widespread misuse of funds, particularly by a global cadre of questionable investment advisers.

The Nauruan government eventually went bankrupt and in exchange for a multi-pronged bailout Australia became involved in its administration, continued mining and then created "the Pacific Solution," which established Nauru as a refugee detention center in 2001.See Greg Fry, "The Pacific Solution?" in Maley et al., Refugees and the Myth of the Borderless World (Canberra: Dept. of International Relations, RSPAS), 23–31. The failure of the Nauru-Australia rehabilitation efforts set up in 2010 was described by Leon Surawksi, former employee of the Nauru Rehabilitation Corporation: "It’s a serious situation because there’s insufficient land to produce food for the population of Nauru...there’s no income, no means of producing food from the land...Nauru is in a very serious situation." Stoler asks:

What remains in the aftershocks of empire? Such effects reside in the corroded hollows of landscapes ... The question is pointed: How do imperial formations persist in their material debris, in ruined landscapes and through the social ruination of people’s lives?

Structural ruptures to Pacific cultures, such as those initiated by the introduction of Christianity, colonialism and mining, become compounded in complex material, economic, political and spiritual ways.

The resulting societies and states are often characterized by political scientists, international relations experts and political journalists from former colonial metropoles as unstable and corrupt. Greg Fry, analyzing the rise of a Pacific doomsday discourse constructed by Australian scholars, journalists and policy makers, critiqued this stance and Australia’s presumption of authority over the South Pacific in the 1990s:See Greg Fry, "The Pacific Solution?" in Maley et al., Refugees and the Myth of the Borderless World (Canberra: Dept. of International Relations, RSPAS), 30.

Like earlier Australian depictions of the Pacific Islands, the new doomsday- ism provides an interesting sounding of how Australians see themselves. At the center of such conceptions has been an unquestioned, and often unacknowledged, belief that Australia has a right, or even a duty, to speak for the inhabitants of this region, to represent them to themselves and to others, to lead, and to manage them. This belief was asserted long before Australia had the power to enforce it, indeed even before Australia was formally established in 1901 ... Australian policymakers continued to assert this belief over the next century, particularly at the end of the two world wars, and even more strongly from the mid-1970s, when Australia saw itself as the natural leader of the postcolonial South Pacific ... Although a familiar tendency in white Australia’s approach to Aborigines (the parallels are striking), the islands region has been the only area outside the continent where Australians have imagined themselves as colonizers and civilizers.

Today, even those to the left of the political spectrum, including many refugee advocates and supporters, have been scathing in their critiques of Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. The charge is that these countries are undesirable and unsuitable for refugees.See for example Thea Cowie, "What Future for Refugees on Manus and Nauru?," SBS (16 January 2014). This was sharply amplified in an incident in which the "Youth of the Republic of Nauru" wrote angry letters to refugees stating:Sarah Whyte, "Nauruan Letter Threatens Island’s Refugees and Asylum Seekers," Sydney Morning Herald, 18 November 2014. "Refugees are taking over all our job opportunities and spreading over our small congested community, making our lives miserable ... "

Clearly little had been put in place to raise awareness and understanding between refugee and Nauruan populations and little is said of Australia’s historical relationship of structural imperialism and exploitation of its Pacific neighbors. So when Nauruans respond to refugees and Australian personnel in less than hospitable ways they are judged by the Australian public not in terms of this history of structural exploitation, but as reinforcing the widespread belief that the islands are third world backwaters.

The ruin signaled by Stoler is multidimensional, for how else does a place like Nauru, once named "Pleasant Island", become one of inhospitable anger and despair? Much of this has to do with the imperial unravelling of fundamental relationships between islanders and their landscapes, commoditizing such places so that the break in hundreds of years of kinship with the land turns into a series of ruptures between people, each other and others.

This is not to deny agency to Pacific peoples who, since the arrival of Europeans in Oceania, have participated in their own transformation. But such agency does not negate the overwhelming power differential between Islanders and Europeans, a difference that results in the replacement of fresh fish with canned meat, dance with prayer, elders with pastors, businessmen, resident commissioners and eventually civil servants and politicians, and sustainable livelihoods with dependence on money, whether in the form of phosphate royalties or "aid" in the form of a refugee detention center.

Like the Nauruans, how did the Banabans, a people that had survived, and even thrived, on a six-square-kilometer rock island in the remote central Pacific in the face of regular harsh droughts and limited natural resources for two thousand years, become "ruined"?

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Growing the rock

There are several geological studies explaining the origins of phosphate on Banaba but it is worth highlighting the version outlined by British novelist and broadcaster Lucille Iremonger, who gave a lyrical and cynical account based on her visit to the island. In 1948 Iremonger was awarded the Society of Women Journalists’ Lady Britain trophy for the best book of the year for It’s a Bigger Life, chronicling her time in the Pacific as the wife of a colonial officer. She wrote:Lucille Iremonger, It’s a Bigger Life (London: Hutchinson, 1948).

Every time anyone opened his mouth on Ocean Island the word "phos- phate" came out. In no time, and much against my will, I knew all about it ... Everyone knows how a coral atoll is formed ... To turn a coral atoll into a phosphate island a few more centuries must pass. Very likely it sinks into the sea, once or several times...Sea water percolates through the birds’ deposits, carrying phosphoric acid into the rocks beneath...the acid is automatically converted into phosphate of lime. You have only to treat this with sulphuric acid and, hey presto! Superphosphate!...The British Phosphate Commissioners had added their contribution of weird- ness to ugliness. In the trail of their craggy diggings in the limestone bedrock they had left behind them strange shapes, ragged bumps, columns and protuberances of every sort. Row upon row of gnarled pinna- cles of porous rock as tall as trees gave the place a look as of some mediaeval inferno ... For hundreds of thousands of years the slow process of making an island like this had gone on. Then one day a man struck his foot against a "coral" door-stop in a Sydney office, and phosphate was discovered. The life of a Pacific island was changed before the inhabitants knew anything about it. The natives became rich, and the island was destroyed.

Ocean Island origins

Banaban oral history, as told to the late Professor H. E. Maude by Nei Tearia and Te Itirake in the 1930s, describes the origins of Banaba or "rock land"; "aba" also meaning "the people." Their stories combined describe how in the beginning heaven:

... was a rock lying over earth and rooted in the deep places of the sea. All the lands of the ancestors were embedded in the rock and stood out like hills atop it. Banaba was the buto, the navel, and all the multitude of lands and ancestors in Te Bongiro, the darkness, lay around it. Tabakea, the turtle lived on Banaba with Nakaa, his brother, Auriaria the giant, Tabuariki the shark and thunder, their sister, Tituabine, the stingray and lightning, and many others...Auriaria became the lord of Te Bongiro and he pierced the heavens with his staff. The rock fell into the sea, upside down with its roots in the air, burying Tabakea underneath. Auriaria then traveled southward until his foot struck a reef-rock. There he stayed and made a great land which he called Samoa. He met a razor clam called Katati which he flung into the East and that was the Sun. And again he took a shellfish called Nimatanin, and that was the Moon. Then he took the body of Riki, the eel, and laid it across the sky ... it is now the Milky Way. Then Auriaria planted a tree on Samoa, from which sprang a host of ancestors.

Maude wrote that Auriaria then returned to Banaba and his children are there to this day. But Auriaria’s children are not there but rather are spread across the Pacific after a process of forced migration. The Banabans were moved to Fiji in 1945 and in 1977 were offered a small ex-gratia payout of 10 million AUD for eighty years of mining and an unrecognizable landscape; they now struggle to support livelihoods across two home islands. There are now about 400 people on Banaba, 3,000 on Rabiband more across the Pacific, receiving minimal infra- structure or resources from the respective Kiribati and Fiji governments. My research was a process of tracking both the fragmented landscape and displaced population across Oceania, starting first with a visit to the now truly isolated island in 1997:

I arrived on Banaba on a government boat filled with all manner of cargo: women and children ... freely wandering chickens, ducks and dogs, tinned food of various sizes, sacks of rice, kilograms of pounded, paper-bagged kava ... In the absence of light of any kind, we somehow managed to dis- embark clutching our bags, and ascend slippery invisible steps ... I was placed on the back of a...motorbike which...sped up a bumpy, dark road to a grand but dilapidated house ... the building was ... named after Sir Albert Ellis, the man who had discovered phosphate on Ocean Island and Nauru in 1900. After a night mostly devoid of sleep I awoke to an extraordinary view. Banaba was a desiccated field of rocks and jagged limestone pinnacles jutting out of a grey earth with patches of dark green foliage. Roofless concrete buildings, rusted machines and corrugated iron warehouses littered the vista punctuated here and there by startling red flame trees and coconut trunks devoid of fronds ... The combination of jagged rock, rusted iron, and vast blue sea signaled not an idyllic island scene, but an industrial, oceanic wasteland.

Reflection

The Banaban story is one of cultural devastation and transformation illustrating the enduring effects of imperialism, but there are many more dimensions to

this history. I have presented just a few here but will end on a more personal note. In the early 1990s my elder sister, Teresia Teaiwa, now a long serving secretary of the Pacific History Association, was put off from pursuing Banaban history by Professor Maude after he responded harshly to a letter seeking his expert advice on her proposed Ph.D. topic on Banaban gender relations, a theme absent in the archives and most published works. Maude, writing from Canberra, was of the opinion that a Banaban woman planning research, as she was, on the oral histories of other Banaban women would be dealing with "emotive" content and she would not be able to produce anything of a serious scholarly nature. He also wrote:

My wife and I were happy to meet ... members of the Rabi Island Council on our last visit to Suva, when we were given an official dinner to thank me for having bought such a lovely island for them and to assure us that after many vicissitudes they were all happily settled in their new home, with only a handful of unimwane and unaine [male and female elders] still desirous to return to Banaba to have their bones buried beside those of their forebears.

Teresia Teaiwa changed her research topic, but six years later wrote:

The whole reason for Banaban displacement is colonial agriculture. I like to say "agriculture is not in our blood, but our blood is in agriculture". if Banabans think of blood and land as one and the same, it follows then that in losing their land, they lost their blood. in losing their phosphate to agriculture, they have spilled their blood in different lands. their essential roots on ocean island are now essentially routes to other places. places like Fiji, New Zealand, and Australia.

As asylum seekers from across the globe seeking refuge in Australia are diverted to phosphate islands, one can, with knowledge of phosphate histories, imagine the ways in which the trajectories of both rocks and peoples intersect and illuminate the less than honorable relationships Australia has with particular peoples and places across the sea of islands.

The original and full text was published 2015 in Volume 46 of the Australian Historical Studies Journal under the title "Ruining Pacific Islands: Australia's Phosphate Imperialism."

According to ornithological speculation, the first sea birds appeared approximately 200 million years ago.

According to geological speculation, the island of Nauru appeared 50 million years ago.

According to historic speculation, Micronesian and Polynesian people inhabited Nauru about 3000 years ago.

According to the logbook of the British whaling ship "Hunter," its crew were the first Europeans to encounter the island in 1798. The crew did not set foot on the island and the Nauruans did not board the ship. Captain John Fearn named it Pleasant Island.

According to a recently published history book, the first Europeans to live on Nauru in 1830, were escaped Irish convicts Patrick Burke and John Jones (later referred to as "Nauru's first and last dictator"). The Nauruans banished Jones from the island in 1841.

According to "Grundbuch Marshall-Inseln und Nauru" Prussian officials abolished the name Pleasant Island in 1888. Nauru was annexed by Germany and incorporated into the‚ Marshall Island’s Protectorate. The German gunboat SMS Eber landed 36 men on Nauru and took the twelve clan chiefs of Nauru hostage. Kings were established as rulers of the island.

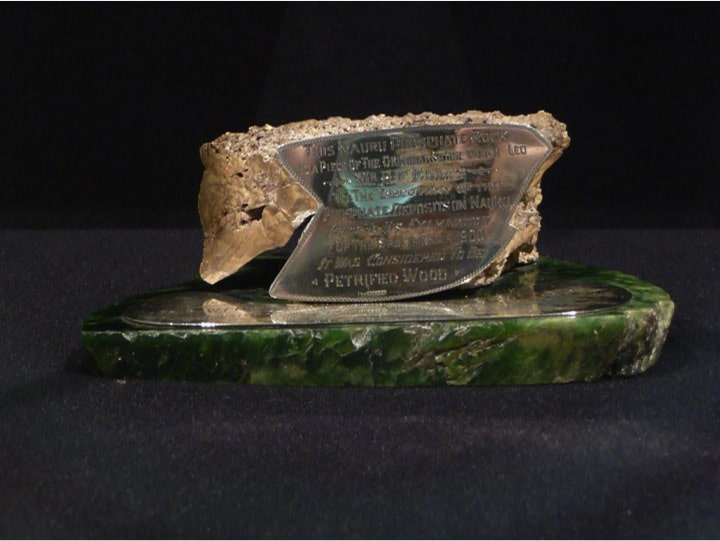

According to the company books, Albert Ellis, prospector of the British Pacific Islands Company discovered phosphate on Nauru in 1900. The resource derives from a thousand-year cycle of bird droppings as they follow million-year-old flight paths across the Pacific. Ellis determined that a large rock from Nauru being used as a doorstop in the company’s Sidney office was rich in phosphate.

According to a contract from 1906, Britain divides the profits from phosphate mining with the German Jaluit-Society.

Nauru is seized by Australian troops from Germany’s colonial administration in 1914. According to article 119 of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany renounces all rights over Nauru and other territories in the Western Pacific in 1919.

According to the Nauru Island Agreement Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom created a board known as the British Phosphate Commission. It took over the rights to phosphate mining in 1919.

According to medical records by the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, the island experienced an influenza epidemic in 1920, with a mortality rate of 18% among native Nauruans.

According to war reports, the German auxiliary cruisers "Komet" and "Orion" sank five supply ships in the vicinity of Nauru on 6 and 7 December 1940. Komet then shelled Nauru's phosphate mining areas, oil storage depots, and the shiploading cantilever.

According to a post-war study conducted by the Australian military, Nauru is occupied by Japanese troops. 1,200 Nauruans, two-thirds of the population, are deported to Micronesia to work as forced laborers. Five hundred die from starvation or bombing.

1947 – Nauru is made UN Trust Territory under Australian administration.

1965 – The one-hit wonder "Unit 4 + 2" knocks "The Rolling Stones" off the number one spot in the charts with "Concrete and Clay."

1966 – Nauru Legislative Council elected.

1967 – Nauruans gain control of phosphate mining through Nauru Phosphate Royalities Trust, a sovereign wealth fund that distributes mining profits from the state owned mining company, The Nauru Phosphate Corporation.

1968 – Nauru becomes independent. Hammer DeRobert becomes its first president.

1969 – Nauru becomes associate member of Commonwealth.

1972 – The Nauru Government builds "Nauru House" – a 52-story skyscraper designed by architectural firm Perrott Lyon Timlock & Kesa at 80 Collins St, Melbourne. The building was sold in 2004 for 140 million Australian dollars.

1980’s – Due to global market forces, the price of phosphate soars, giving 80,000 Nauruans the highest per capita income in the world for several years.

1989 – United Nations Report for Pacific Island Developing Countries on greenhouse effect warns Nauru might disappear beneath the sea in the 21st Century.

1989 – Nauru sues Australia in the International Court of Justice for additional phosphate royalties dating back to trusteeship period, and compensation for mining damage.

1992 – Duke Minks a 47-year-old Liverpudlian, an adviser to the Nauruan government, and former road manager to Sixties one-hit wonder pop group "Unit 4 + 2" brings a tape recorder into the Nauruan parliament and plays extracts from the planned London musical "Leonardo the Musical – a Portrait of Love," featuring lyrics by the group’s former singer Tommy Moeller. He receives two million pounds to finance the musical – an investment that will supposedly help to put Nauru on the map and will pay back in dividends over the years.

1993 – Australia agrees to pay Nauru out-of-court settlement of 73m Australian dollars over 20 years. New Zealand and the UK agree to pay a one-time settlement of 8.2 million each.

June 1993 – More than 150 Nauruan dignitaries, including president Dowiyogo, are due to fly to London for the opening night of the musical "Leonardo." As the pilot prepares the Nauru Air 737 for take-off, people, mostly women, swarm the tarmac to prevent the plane from leaving, yelling in protest and hanging onto the aircraft to try and keep it aground. The incident is later recognized as the first time women on Nauru started to organize.

June 1993 – Leonardo da Vinci slaps the Mona Lisa on the bum, and asks her to “help me with my research” at the premiere of the "Leonardo" musical.

July 1993 – The musical closes, with huge financial losses, within weeks due to terrible reviews.

1995 – The Bank of Nauru collapses.

1997 – Nauru Agency Corporation is a government body that handles state investments. It has one standard mailbox and 450 banks registered to it.

1997 – Duke Minks leaves music behind for the banking world, eventually becoming an executive of Citibank Australia, where Nauru was a major client.

1998 – According to Victor Melnikov, Deputy Chairman of the Russian Central Bank, and both The Washington Post and The New York Times, between 70-100 billion dollars were transferred from Russian banks to accounts of banks chartered in Nauru, primarily to evade taxes, making it a hub for global off-shore banking.

1999 – Nauru joins the United Nations.

2000 – The OECD lists Nauru in its Plenary Report as a global epicenter of offshore tax havens and money laundering. Nauru is listed as a "Non-Cooperative Country or Territory."

2000 to 2003 – The USA classify Nauru as a rogue state for money laundering and indiscriminate sale of passports.

2001 – Australian Prime Minister John Howard initiates ‘The Pacific Solution’. Australia pays Nauru to hold asylum seekers picked up trying to enter the country.

December 2003 – Asylum seekers at Australia's offshore detention center on Nauru stage a hunger strike.

April 2004 onwards – Nauru defaults on loan payments, its assets are placed in receivership in Australia.

July 2004 – Australia sends officials to take charge of Nauru's state finances.

September 2004– President Scotty sacks parliament after it fails to pass reform budget by deadline.

2005 – The Australian government refuses to rule Nauru out as a potential site for an off-shore nuclear waste plant.

2005 – Mining has devastated about 80% of Nauru's land area, 40% of marine life is estimated to have been killed by silt and phosphate runoff.

December 2005 – Air Nauru's only aircraft is repossessed by a US bank after the country fails to make debt repayments.

September 2006 – Australia sends Burmese asylum seekers to Nauru.

March 2007 – Australia sends Sri Lankan asylum seekers to Nauru.

February 2008 – Under Prime Minister Rudd, Australia ends its policy of sending asylum seekers into detention on small Pacific islands, with the last refugees leaving Nauru.

January 2012 – Australia begins process of re-opening detention centers on Nauru at a cost of over 2 billion dollars.

May 2016 – Omid, a 23-year-old Iranian refugee sets himself alight on Nauru, during a visit by United Nations refugee officials to the island.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter