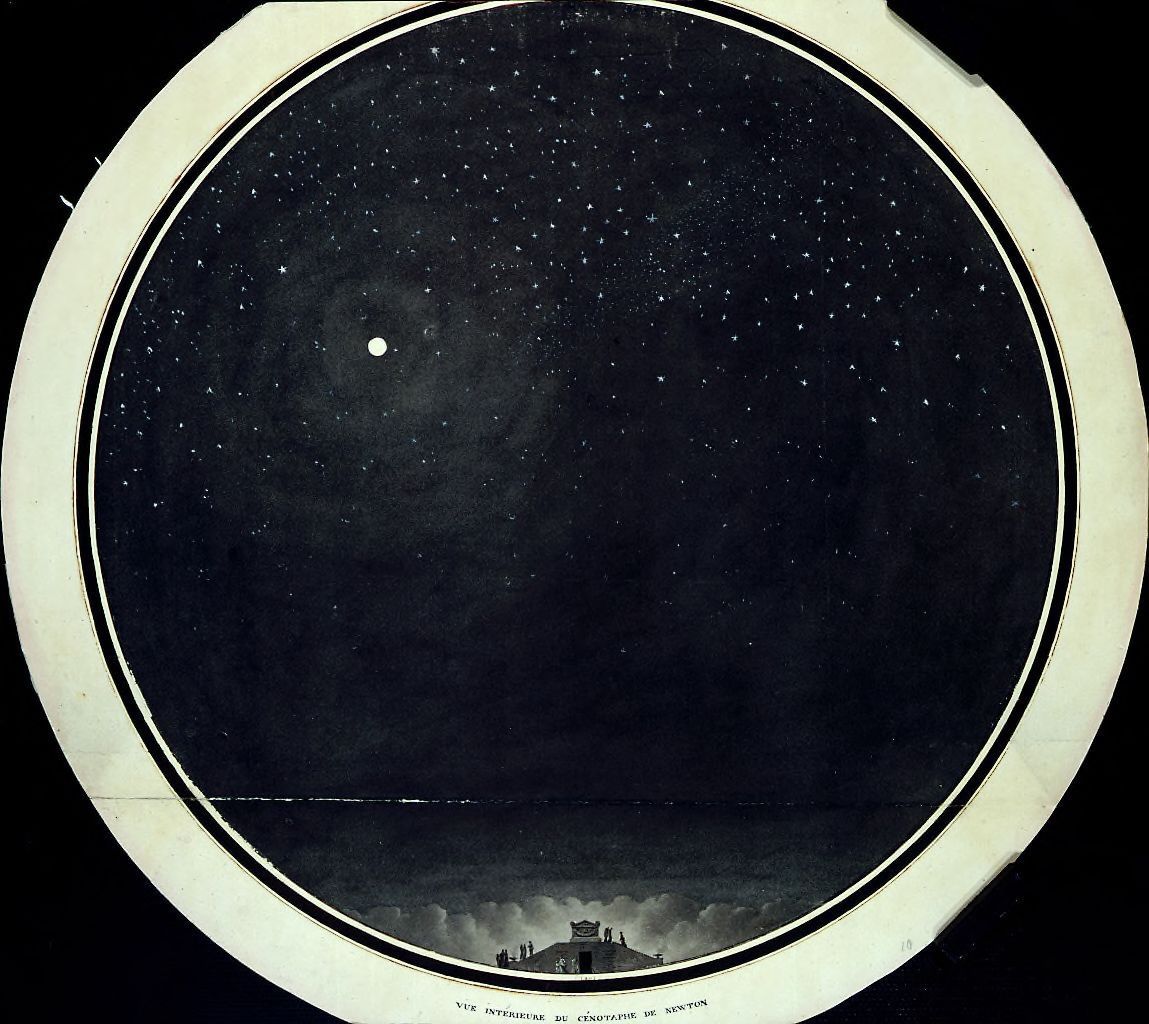

Etienne-Louis Boullée, 1784. Cénotaphe de Newton. Page 6, vue intérieure

Source: Wiki commons

The Origin of the Idea of Material and Life Cycles in the Ancient Cosmos of Concentric Spheres

Why does the world not come to a standstill? This question is positioned at the crest of the modern understanding of terrestrial cycles and spheres. In this article historian of science Pietro Daniel Omodeo unpacks the original, and thus, literal notion of the spheres—from their genuine context in ancient and early modern cosmology and metaphysical doctrine—and comments on the forfeiture of stability threatening today’s spheres.

What shows that the spherical body is the best of all bodies is the fact that it does not perish and that it moves with the motion which precedes all motions, and also that it moves with it eternally and regularly.Alexander of Aphrodisias, On the Cosmos

The shape of the heaven is of necessity spherical; for that is the shape most appropriate to its substance and also by nature primary.Aristotle, De coelo II.4, 286b9–10

And he [the Demiurge] bestowed on it the shape which was befitting and akin. Now for that Living Creature which is designed to embrace within itself all living creatures the fitting shape will be that which comprises within itself all the shapes there are; wherefore He wrought it into a round, in the shape of a sphere, equidistant in all directions from the center to the extremities, which of all shapes is the most perfect and the most self-similar.Plato, Timaeus 33b

We live in a world of spheres. Within the larger system of the geosphere many subsystems unfold and entwine their material cycles—the hydrosphere and the atmosphere weave together with the more limited lithosphere and cryosphere. The biosphere, the “layer” of life and its cycles, has been complemented by mental and artificial spheres such as the Vernadskyian noosphere and the most successful newcomer, the technosphere. To be sure, we have to understand our modern spheres metaphorically, the sphere being the symbol of self-regulating closeness; and yet they stem from ancient visions that literally posited the existence of perfectly spherical bodies in nature. In this essay, I will reconstruct the ancient, cosmological roots of the very idea that stable natural processes can be understood as “cycles”. In fact, they were initially brought back into the circular motion of the perfectly spherical bodies of the heavens.

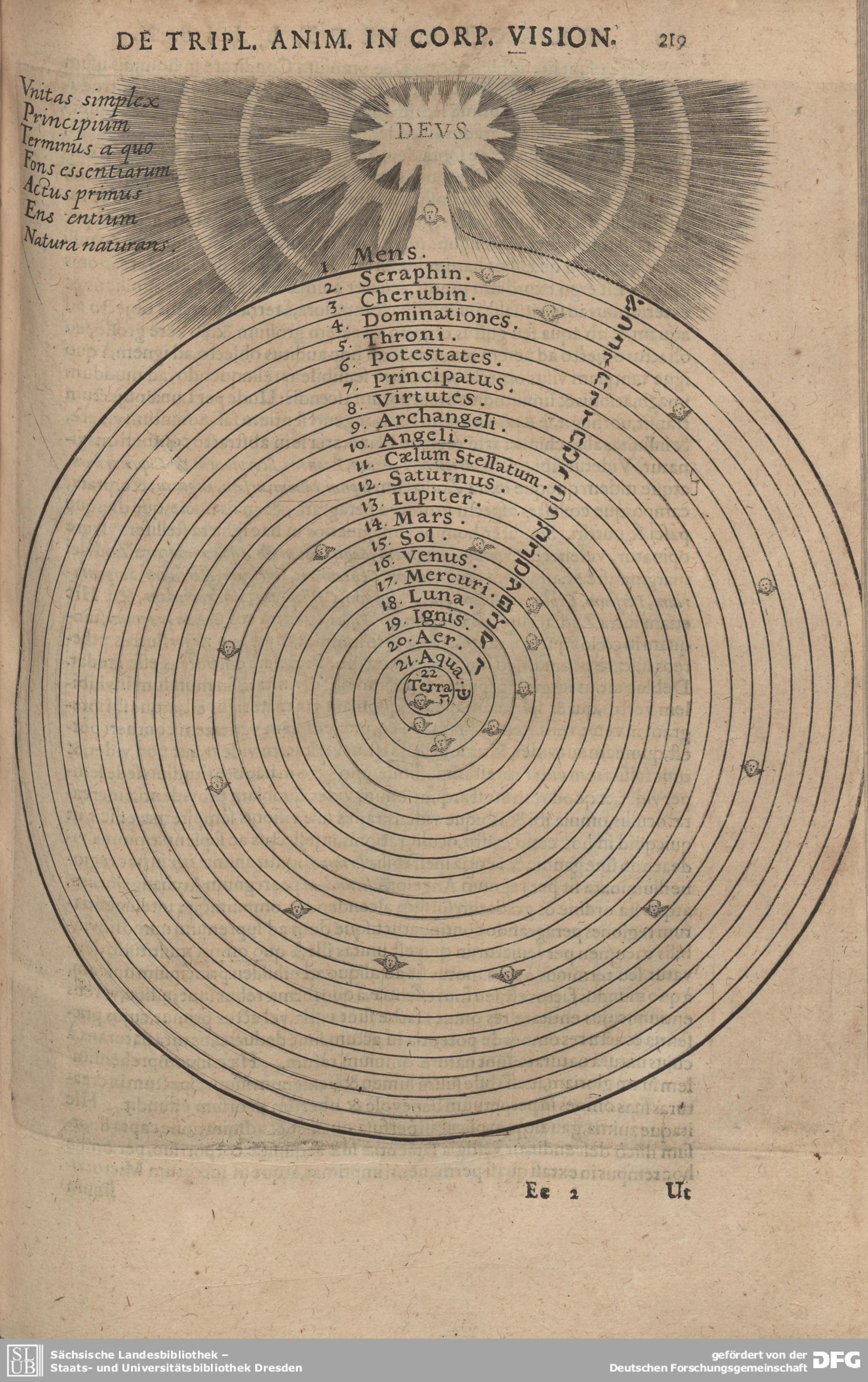

The cosmological spheres of the ancient worldview were ethereal orbs deputed to transport stars and planets in circular motion. Thanks to their geometrical form they were allotted the divine privilege of eternal motion: “There is no continuous movement except movement in place, and of this only that which is circular is continuous”—Aristotle stated with crystalline clarity in the Metaphysics.Aristotle, Metaphysics XII.6, 1071b10–11, cf. Metaphysics, ed. C. D. C. Reeve. Cambridge, MA and Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2016, p. 203. Drawing on these premises, Aristotle’s followers saw the spherical shape as the precondition of circular motion, which they considered to be the only never-ending displacement in nature. In fact, its end coincides with its beginning. In the Latin Middle Ages, “sphaera” became then a synonym of the uppermost heaven, thought of as the starry boundary of the material world. According to theological conceptions still in circulation in the seventeenth century, the orb of “fixed” stars was embraced by the Empyreum, the immaterial seat of blessed souls, saints, and angels according to the hierarchical chain of beings that connects the lowest realm to God (Figure 1).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

One can hardly find a better representation of the material cosmos of concentric spheres than the diagram (Figure 2) that is often included in manuscripts and early editions of Johannes de Sacrobosco’s De sphaera (On the Sphere), the standard textbook on spherical astronomy in the art faculties of medieval and early modern universities.See Lynn Thorndike, The Sphere of Sacrobosco and its Commentators. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1949; and Michel-Pierre Lerner, Le Monde des spheres: Vol. 1, Genèse et triomphe d’une représentation cosmique; Vol. 2, La fin du cosmos classique. Paris: Les Belles Lettres,

1996–97. At the beginning of his tract Sacrobosco introduced the Aristotelian distinction of “two physics,” sublunary and superlunary. While the heavens move according to the most perfect motion (that is, as we already know, in circles), the elements move in straight lines, upwards (air and fire) or downwards (water and earth), unless impeded from doing so by some occurrence or “violence.” In the diagrams that accompany these tracts, the highest sphere is that of the fixed stars; it encloses a series of lower planetary orbs, among them those transporting the Sun and, closest to us, the Moon. The sublunary realm occupies the innermost place and is partitioned in concentric spheres as well. The sublunary spherical partitions represent the so-called “natural places,” which the four elements incessantly aim to reach in accordance with their nature. These are: fire, air, water, and, at the center of the world and coincident with the center of gravity, the earth.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

A certain discrepancy between the geometrical scheme and reality is unavoidable since the elements often intermingle, the boundaries of their “natural places” are permeable, and their contours are blurred. Ontological imprecision notwithstanding, cosmological diagrams continued to display four idealized elementary spheres throughout the fifteenth century in the incunable Tractatus de sphaera (Treatise on the Sphere) (Figure 2). The earth was often represented as a disc with the letter “T” engraved on it, this tau was the carrier of a geographical meaning as well as a theological one, as it signified the holy cross as well as the Mediterranean Sea dividing the world into three continents (Europe, Africa, Asia). At the time of the European conquest of America and the discovery of the “Antipodes” (people living upside down on the opposite side of the globe) it became evident that the mass of the land outside the oceans was not just a little earth cup, the limited orbis terrarum imagined by the ancient geographers; instead, continents were irregularly distributed all over the globe. In light of this discovery the earth ceased to be seen as an elementary sphere included in that of the waters, only partially emerging from the ocean thanks to a providential mismatch between the centers of the two spheres, it was now established that we inhabit an “earthly-watery globe” (a globus terraquaeus), the image of which appears in post-Columbian cosmological diagrams. These innovations notwithstanding, the general structure of the concentric-spheres cosmos was not about to be abandoned. Despite the emergence of the in(de)finite universe idea—e.g. in the post-Copernican conception of philosophers such as Giordano Bruno, René Descartes, and their followersPietro Daniel Omodeo, Copernicus in the Cultural Debates of the Renaissance: Reception, Legacy, Transformation, Medieval and Early Modern Philosophy and Science, vol. 23. Leiden: Brill, 2014, chapter 4.—the standard teaching of “celestial physics” remained as conveyed by Aristotle in De coelo (On the Heavens).Aristotle, On the Heavens (De coelo), in The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes, vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984, pp. 447–511. Here, the heavenly and elementary spheres are approached one after the other (in books I–II and III–IV, respectively) according to their supposed physical contiguity and continuity. The world of the spheres lived on, long after alternative worldviews emerged.

Yet, order does not imply motion. A disposition is not an explanation for motion just as the ascertainment of “structures” underlying the phenomena does not explain their dynamics, unless causes are introduced to account for the genesis and persistence of systemic processes.Aristotle, On the Heavens (De coelo), in The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes, vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984, pp. 447–511. In De generatione et corruptione (On Coming to Be and Passing Away), a work devoted to generation, life, and death, Aristotle raised the crucial question (II, 337a8–11): “what is to some people a baffling problem—viz. why the simple bodies [the elements], since each of them is travelling towards its own place, have not become dissevered from each another in the infinite lapse of time.”Aristotle, De generatione et corruptione, in W. D. Ross (ed.), The Student’s Oxford Aristotle, vol. 2. London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1942. Why does the world not come to a standstill? What is the reason for the stability of such terrestrial cycles ranging from material transformations to life processes? Such questions concern the genesis, endurance, and even goals of the spheres; it is, in one word, the quest for causes, including teleological ones. This intuition can be seen as the structural inception or, rather, as the premodern basis of the later, metaphorical usage of the term “spheres.” It refers to their main feature—i.e. recurrent dynamic stability—and implies related questions about what causes the material and life cycles in nature, and the question of what keeps them going. In this respect natural philosophers from the Latin Middle Ages distinguished between the so-called “quia,”—the observed cyclic phenomena seen as facts—and the “propter quid,” their causes. Each should be taken into account for a sound explanation of nature.

A tentative answer to the question about the causes of natural cycles can be found in Aristotle’s elementary doctrine; such doctrine occupies a key position in his natural philosophy. It is addressed in the second part of De coelo and in the two books of De generatione et corruptione, functioning to connect the general theory of motion and of the heavens in Physics and De coelo I–II with the explanation of meteorological phenomena specifically expounded in the Meteorologica. Aristotle characterized the corporeal elements as couples of opposite tactile qualities: heat and coldness, wetness and dryness, of which he admitted only four combinations. Moreover, he did not see the elements as stable. According to him they are constantly intermixed, transforming into one another. These conversions are not the effect of an internal impetus; he posited external causes which produce specific qualities by their action on prime matter (the universal material substrate). These causes are heavenly: the displacement of the Sun along the ecliptic is the proper cause of material and life cycles, while the steady, daily motion of the heavens around the poles of the world is the source of continuity for the sublunary processes.This cosmological idea, expounded in De generatione et corruptione is repeated at a higher level of abstraction in Metaphysics XII.

The celestial origin of terrestrial cycles was to become a stock medieval argument in favor of astrology, seen at the time as the science of heavenly influences. The solar causation of seasonal changes was equated to the lunar causation of tidal movements in reference works such as Albumasar’s Introductorium in astronomiam [Introduction to Astronomy].Albumasar, Introductorium in astronomiam. Venice: Sessa, 1506, ff. a3r-v. Solar–lunar conjunctions and oppositions accounted for the ebb and the flow, regarded as the effect of a cosmic sympathy between the waters and the Moon—an occult, distant action that bears more resemblance to Newtonian gravitation theory than to the mechanical explanations of Galileo and Descartes.

Hence, in order to trace the origin of terrestrial cyclic phenomena such as seasonal change, the Copernicans—just like the Aristotelians—lifted their eyes in search of astronomical causes. Still, cosmological causation does not solve the problem of the origin of motion in the world system, but only shifts it, for two reasons. Firstly, even celestial phenomena are not as regular as the principle of perfect circularity assumes. Secondly, their causes have to be detected, as well.

Early fifteenth-century celestial physics in Europe was marked by the convergent reception of two Islamic authors who envisaged a solution to the incongruity between the axiom of circular motion and observed phenomena. Ibn Rushd (Averroes) in his most celebrated commentaries on Aristotle’s Metaphysics and al-Bitruji (Alpetragius) in Planetarum theorica physicis rationibus probate (Planetary Theory Demonstrated Through Physical Proof) envisaged a program of “physical mathematics” aimed at tracing all astronomical phenomena back to sets of circular motions produced by the motion of concentric ethereal spheres. Aristotelians of the Padua School such as Girolamo Fracastoro and Giovanni Battista Amico were particularly receptive to these theoretical debates. It was argued that the continuity of the circular motion in the ethereal spheres had to be secured through “cosmo-psychological” considerations as well as metaphysical principles.Alexander of Aphrodisias, 2001; Ibn Rushd (Averroes), De substantia orbis. Critical edition of the Hebrew text, with English trans. by Arthur Hyman. Cambridge, MA, and Jerusalem: Medieval Academy of America, 1986. They assumed that celestial bodies were “ensouled”; moved by an intellectual desire for the divine. The Aristotelian God, the “Immobile Mover” toward which all natural beings strive, constituted the transcendent principle that secured the functioning and endurance of the cosmic machinery.

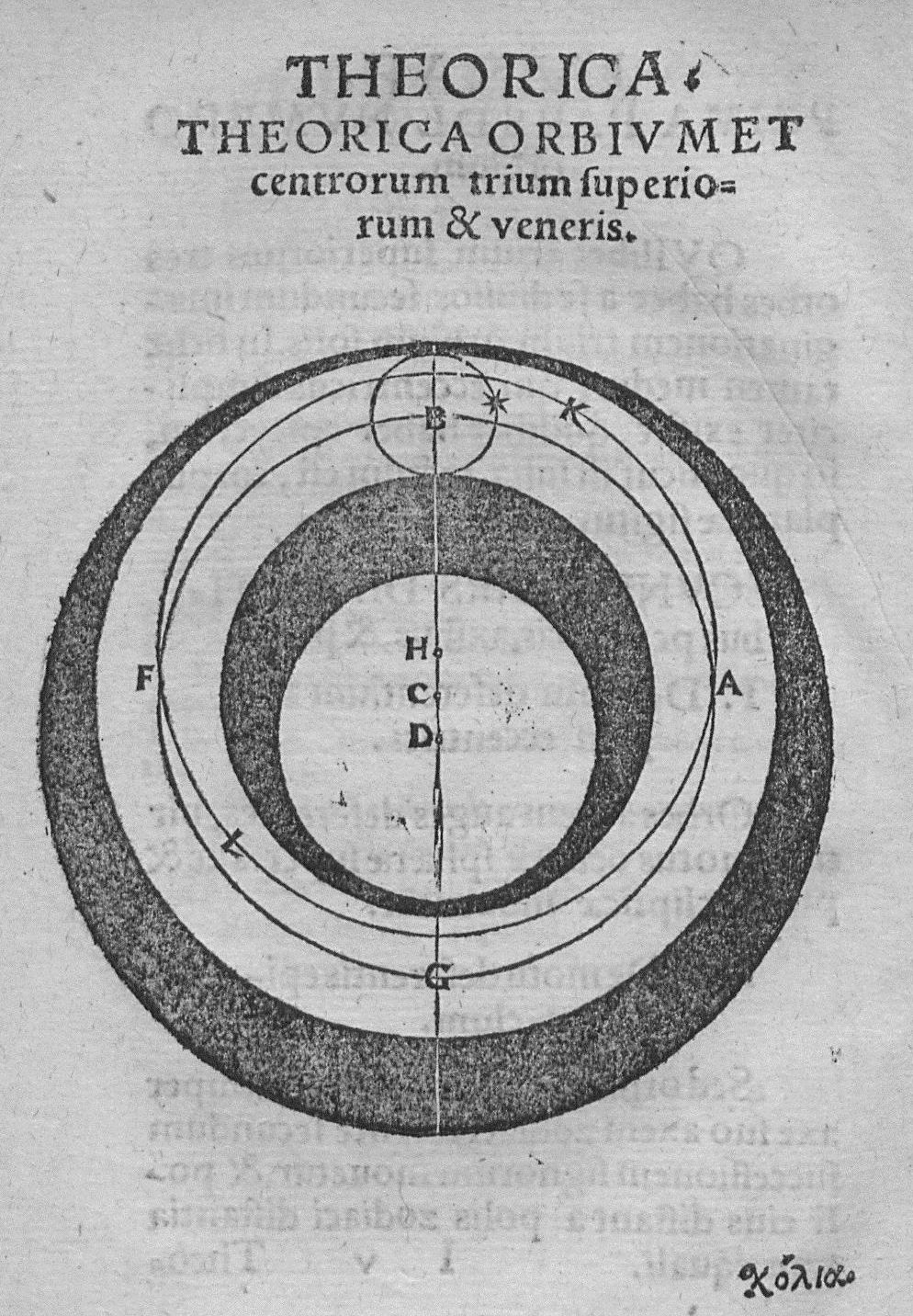

In spite of his ambitious attempt to connect causal and mathematical reasoning, there were major shortcomings in the homocentric approach from its inception. Mathematical astronomers, including Nicolaus Copernicus, objected to the idea that the eccentric and intersecting geometrical devices of the mathematical–astronomical tradition were indispensable to model planetary motions, and thus no concentric spheres could be assumed as leading hypotheses for astronomical inquiry. In fact, epicyclical models—characterized both by their eccentricity with respect to the cosmological center and by the nesting of circles on circles—accounted, among other things, for planets’ retrograde motions, elongations, and varying distances (Figure 3).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

How could a model of concentric spheres satisfactorily account for these phenomena, and particularly the varying distances of celestial bodies? Contrary to the homocentrists, mathematical-astronomers who followed in the footsteps of Ptolemy offered a different reconciliation of planetary modeling with the material spheres of the Aristotelian tradition. As has been argued, widespread graphic representations of epicyclical models in the standard sources of Renaissance planetary theory represent the ethereal bodies of the celestial spheres as black ink discs; they encircle the mathematical devices of Ptolemaic astronomers. In this manner, one can visualize the planets, transported by Ptolemaic circlets, without transgressing the boundaries of their orbs in the stratigraphy of the onion-like cosmos of concentric spheres (as can be observed in many editions of Georg Peuerbach’s Theorica novae planetarum (New Planetary Theories, 1454), such as in the diagram reproduced as Figure 4, below).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

During the sixteenth century the cosmos of celestial spheres entered an irreversible crisis after it was established that comet trajectories are located outside the sublunary realm and thus freely travel across a fluid cosmic space. Among Renaissance astronomers, Tycho Brahe was the most authoritative critic of the existence of orbs, which he rejected on the basis of the observations and computations relative to the comet of 1577. Not long after him, the fluidity of the heavens became the consensus among many astronomers. Hence, the urgent question arose of how to explain planetary motions after the spheres vanished. The theoretical vacuum left by the ban on the old causal explanation fueled research and eventually led to the novel celestial physics of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton. In passages from Alexander Koyré’s (1957) From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (or better put in context: “From the World of Celestial Spheres to that of Fluid Space”) the concept of the sphere, in referring to natural processes, could only survive as a metaphor.Alexander Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1957. The concrete materiality of spherical bodies that had previously accounted for cycles was abandoned without renouncing the idea of the circular recurrence of phenomena in nature. William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of blood offered a new model that could serve for the interpretation of natural processes in functional terms (according to his own form of revised Aristotelianism), for contemporary vistas in Renaissance vitalism or for later mechanic physiologies and philosophies.

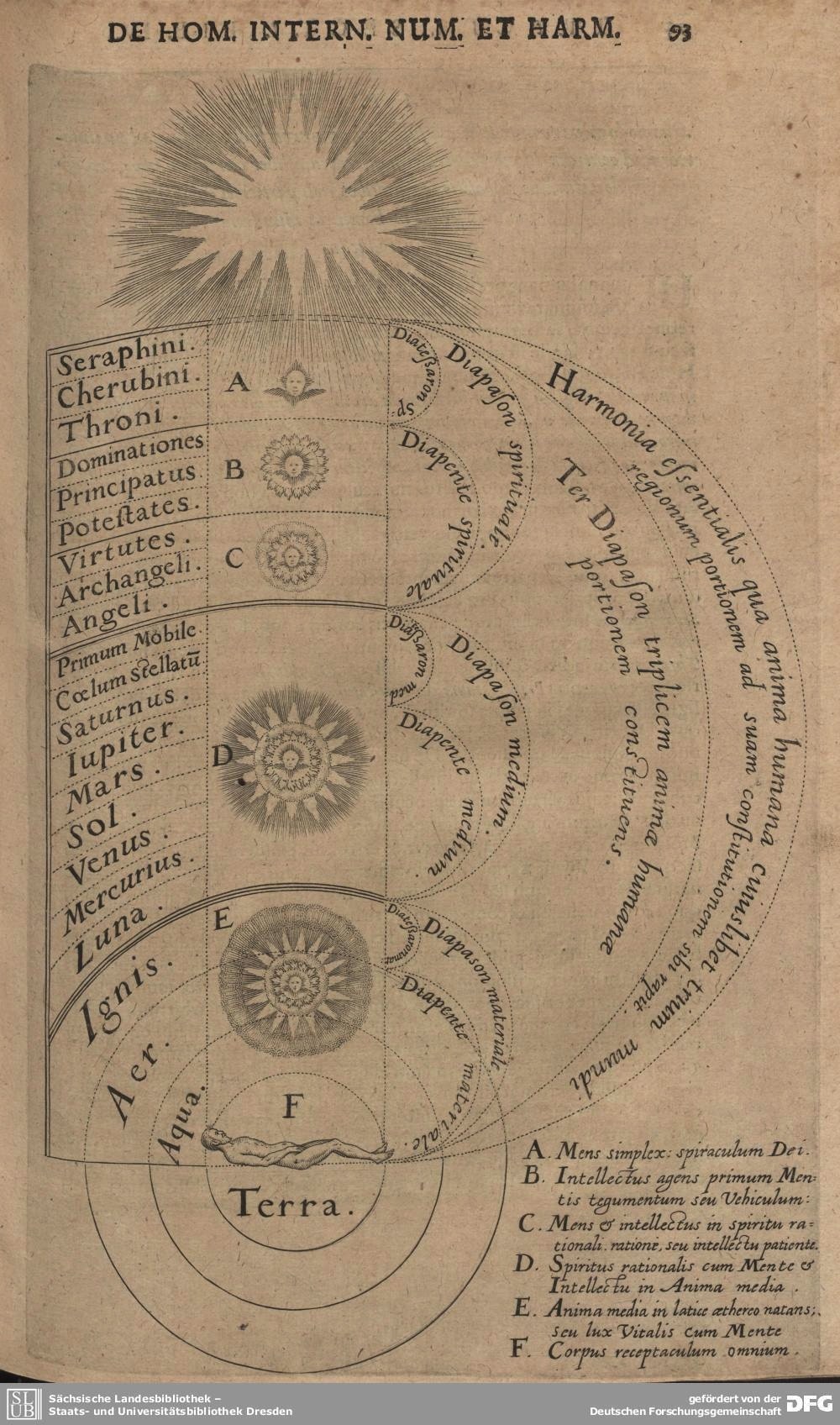

My final remark concerns anthropology. The question addressing the place of humankind accompanied astronomy and had particular relevance in the economy of classical cosmologies. Philosophical sources and astronomical literature from the Renaissance period assumed that a structural correspondence between man and the cosmos existed. The human microcosm was represented at the center of Creation and regarded as the copula mundi, the universal link of nature connecting the inferior reality with the loftier spheres, and the material with the supernatural (Figure 5).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Renaissance anthropocentrism pitted human freedom against natural necessity. The world was the stable stage for our actions and choices. The heavenly spheres accomplished their revolutions in the background, setting the stage for the drama of history. The foundations of that exterior world, either eternal or created during the six days of Genesis, were metaphysical and theological. Dynamic conceptions of physics and biology would eventually discard that static image of nature. However, it is only with the most recent debates concerning the Anthropocene that the modern separation of human action and natural settings has been overcome in consideration of the fact that the technosphere has emerged in a historical time. In this manner, the continuity between nature and human history, which was often assumed with vitalistic conceptions at the threshold of modernity, has been revived from a different viewpoint.

The Anthropocene debate reveals human collective practices as the cause of the emergence of fundamental global transformations, and their dynamic stability. Unlike its ancient and medieval predecessors the technosphere cannot rest on extra-human foundations, therefore its autonomy as a self-regulating system is threatened by the fragility of our biological species, whose survival is endangered by the global dynamics it has set in motion.

Technology is the first geological paradigm complex enough to become aware, through its human components, of the essential contribution to its own existence of the support provided by established paradigms. Whether this awareness will lead to the conservation of a sufficient quantity of natural capital to maintain technological function (and thus the well-being of humans) is the basic question of environmental science. The answer to this question may also determine whether or not the technosphere will, in the long run, become an established rather than a failed geological paradigm.Peter K. Haff, “Technology as a Geological Phenomenon: Implications for Human Well-Being,” in Colin N. Walters et al., A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene. London: Geological Society Special Publications, vol. 395, 2014, pp. 301–09, here 304–05.

Evidently the maintenance of the technosphere and the survival of humanity are interlocked. Both ultimately depend on our capacity to harmonize culture and nature, to express the problem in classical terms. If this task is not achieved, the Anthropocene will not mean the beginning of the geological age of humankind but rather the opposite, an age that comes after the short season in which humankind populated the world. In this light, the Anthropocene proves to be a “task” of collective relevance and, as such, it is political in its essence. In fact, the technical solution can only be addressed from the perspective of a science and humanity emancipated from the anarchy of the present-day economy and from the logic of destruction that accompanies the scientific-technological development that is often assumed transcendent to us.Pietro Daniel Omodeo, “The Politics of Apocalypse: The Immanent Transcendence of Anthropocene,” Stvar: Časopis za teorijske prakse/Journal for Theoretical Practices, 9 (2017): 433-449. The stabilization of our spheres of life is in our hands, as they cannot be secured through metaphysical principles anymore. The Anthropocene predicament calls for political and cultural action aimed at mobilizing the technical and ethical means necessary to stabilize the spheres of the human-made world.