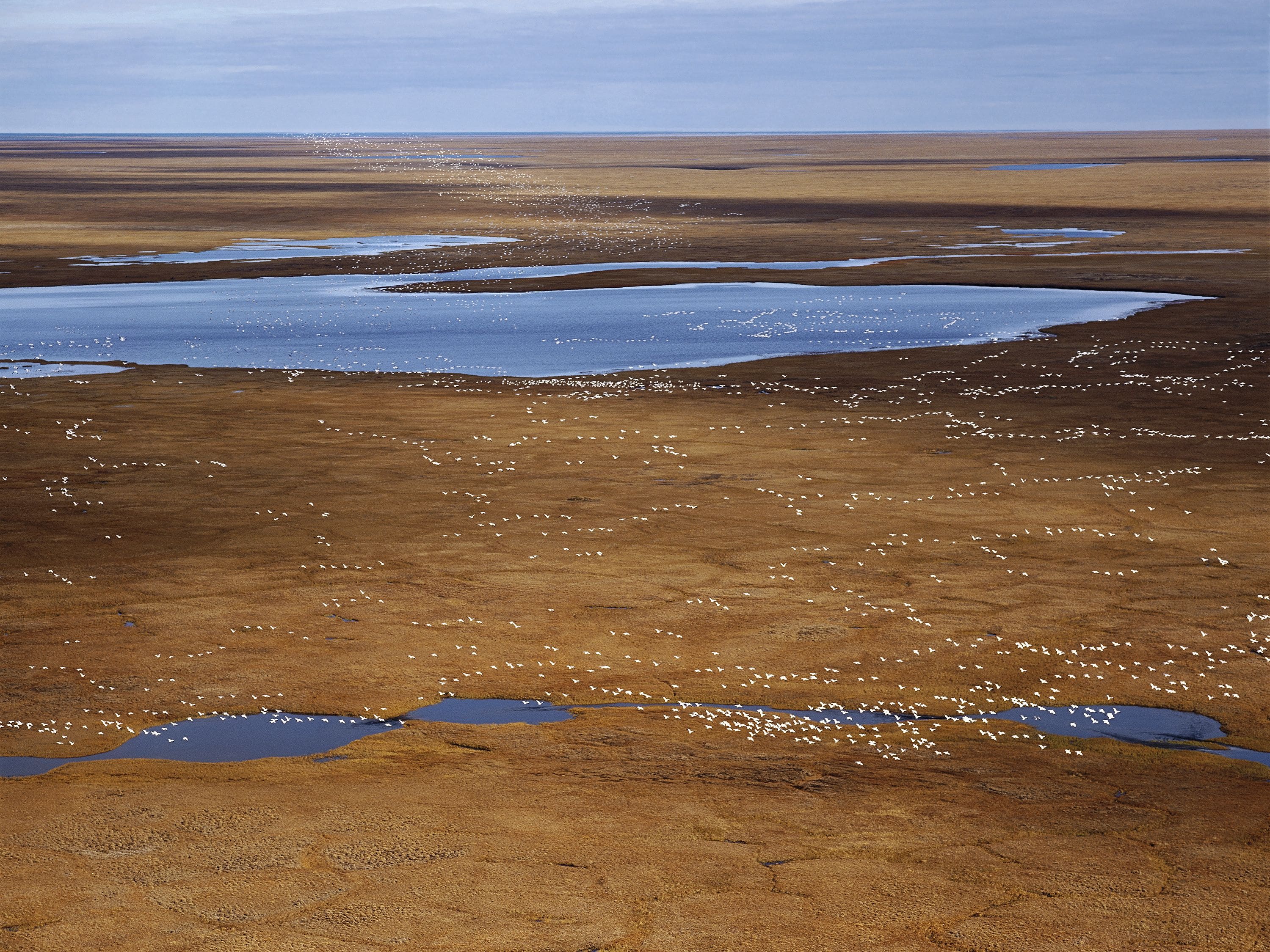

Snow Geese I, coastal plain, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge © Subhankar Banerjee, 2002

The Fight for Alaska's Arctic Has Just Begun

Activist and artist Subhankar Banerjee and engineer Lois Epstein depict the threatening environmental impact of an extractivist technosphere in key protected areas in Alaska’s Arctic. They report on the drastic effects the extraction operations of oil, gas, and coal have on wildlife populations, calling for multispecies justice in the face of the very recently renewed attempt to develop these last pristine environments.

Alaska’s Arctic is a vibrant transnational ecosphere of global significance. It harbors among the highest diversity of species and populations in the region, even though spatially it occupies a relatively small portion of the Circumpolar North. Such a bounty of life has nutritionally, culturally, and spiritually sustained the Iñupiaq, Gwich’in, Koyukon, and Yup’iq for millennia. Indigenous Peoples have also built complex kinship with the nonhuman life, which is expressed in art, stories, and cultural practices.Subhankar Banerjee, Seasons of Life and Land: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Seattle: Mountaineers Books, 2003); A Moral Choice for the United States: The Human Rights Implications for the Gwich’in of Drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Fairbanks, AK: Gwich’in Steering Committee, 2005); Subhankar Banerjee, ed. Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point (New York: Seven Stories, 2012); Ecological Atlas of Alaska's Western Arctic (Anchorage: Audubon Alaska, 2016); and Ecological Atlas of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas (Anchorage: Audubon Alaska, 2017).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

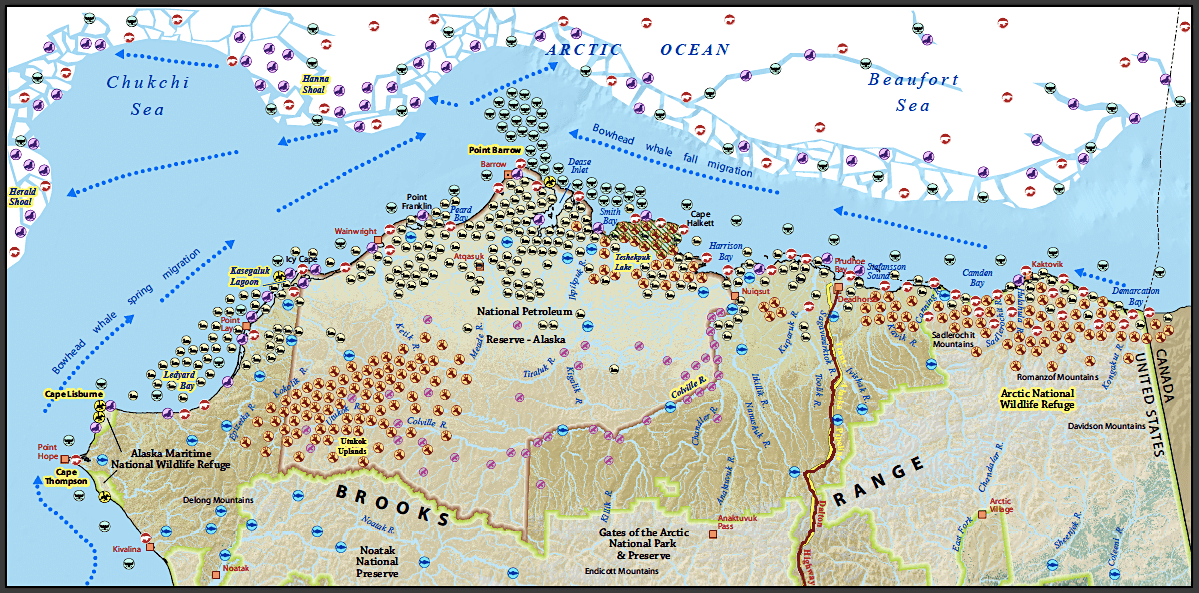

The map Alaska’s Arctic: Selected Wildlife Values & Special Areas makes evident that the land and seas in Arctic Alaska are home to a rich chorus of life. It was produced jointly by the conservation organizations The Wilderness Society and Audubon Alaska in 2010. The various wildlife icons on the map signal abundance and the ecological significance of places, on and offshore, including:

- In the northeast, the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, with about 218,000 animals. These caribou migrate more than 1,500 miles annually from their wintering habitats in the south to their calving grounds on the coastal plain and back again, making it the longest land migration of any mammal on Earth. Fifteen Gwich’in communities in Alaska and the Yukon and Northwest Territories in Canada rely on the Porcupine Caribou Herd. They say, “We are the caribou people.”Sarah James, “We Are the Ones Who Have Everything to Lose (2001, 2009),” in Arctic Voices, 262.

- Situated north-central, the Teshekpuk Lake wetlands, considered to be the largest wetland complex in the Circumpolar North, provide critical nesting and molting habitats for geese and calving and post-calving habitats for caribou.

- In the west, the Utukok Uplands is the calving grounds of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd, with about 235,000 animals. This herd sustains the Iñupiaq, Yup’iq, Koyukon, and non-Indigenous people living in forty communities within the herd’s vast range.

- Further west, along the coast of the Chukchi Sea, is the Kasegaluk Lagoon. At 125 miles long, it is one of the longest coastal lagoons in the Circumpolar North, which provides crucial calving habitat for several thousand beluga whales and habitat for a great variety of birds and fish.

- Just beyond the Kasegaluk Lagoon is Ledyard Bay, where around 500,000 King eiders stop each spring.

- Southwest of Ledyard Bay are Cape Lisburne and Cape Thompson, home to over 650,000 nesting seabirds.

- Just offshore, more than 15,000 bowhead whales migrate through the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas during spring and fall and feed in nutrient-rich areas like the Hanna and Herald Shoals. The Iñupiat rely on bowhead whales for nutritional and cultural sustenance. They speak of the Arctic seas as “our garden”Caroline Cannon, “Testimony in Support of a Legal Suit (2009),” in Arctic Voices, 322. and themselves as “people of the whales.”Chie Sakakibara, “People of the Whales: Climate Change and Cultural Resilience Among Iñupiat of Arctic Alaska,” in “Geographical Perspectives on the Arctic,” special issuem Geographical Review 101, no. 1 (January 2017): 159–84.

- Several thousand polar bears build dens onshore, most importantly in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain, and offshore in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas.

- All the area’s rivers and creeks, shown in light blue on the map, and its thousands of lakes, which are not shown, provide habitats for a host of aquatic and avian species, large and small, iconic and overlooked.

- Millions of birds migrate from all over the world to Alaska’s Arctic to nest and rear their young: from tundra, barrier islands, wetlands, and uplands, to the mountains, the taiga, and the boreal forest.

The Onrush of an Extractivist Technosphere

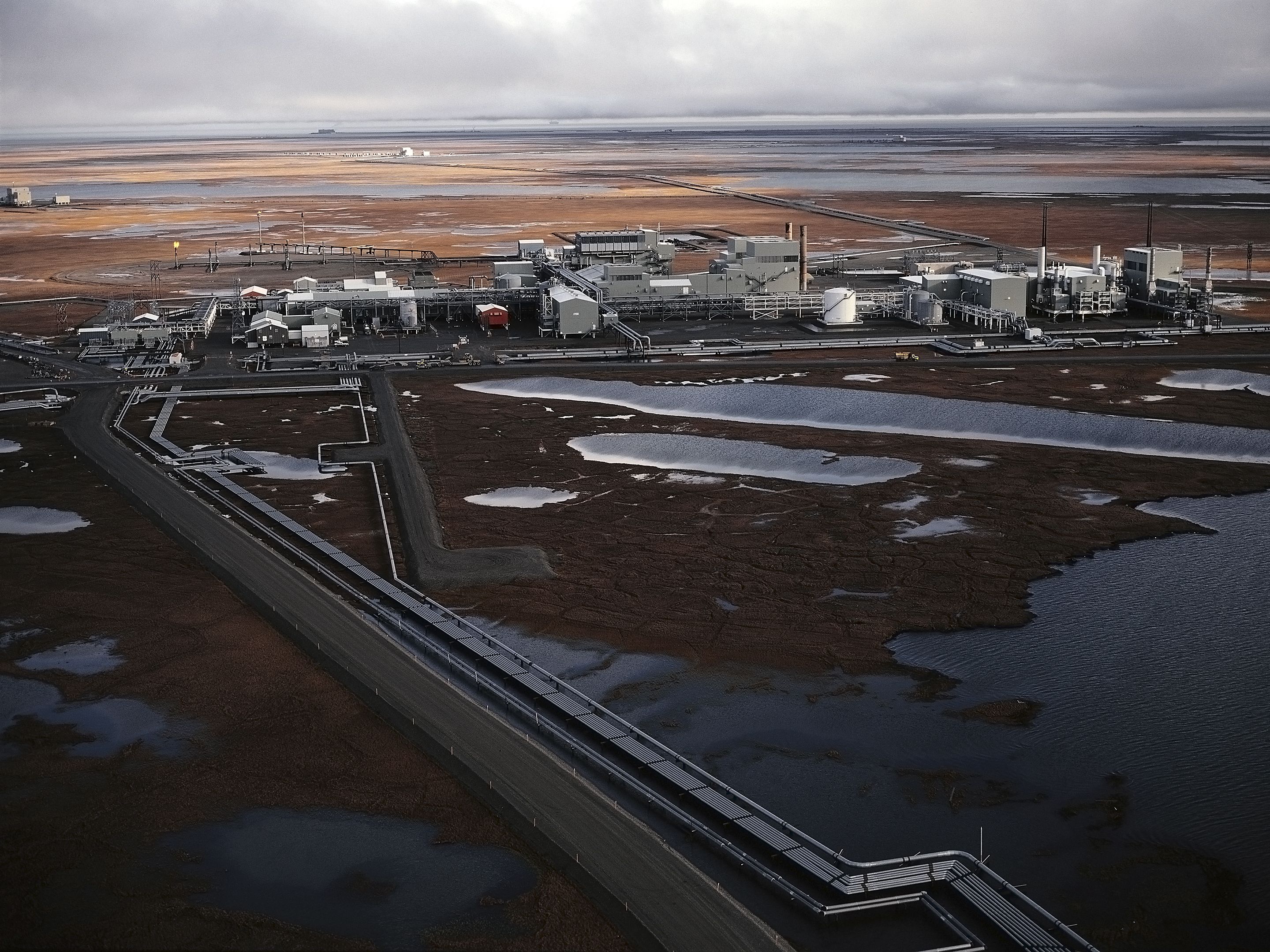

There is an irony to this region, however. Underneath the calving, nesting, denning, and feeding habitats lie vast amounts of oil, gas, —and in the case of the Utukok Uplands, large quantities of coal. Oil was discovered in Prudhoe Bay in the North Slope of Alaska in 1968, and since 1977, crude oil has been flowing through the Trans-Alaska Pipeline from there to the Port of Valdez. While this industrial footprint has steadily expanded east and west, key protected areas like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, and the Kasegaluk Lagoon have remained off-limits to development. The Trump administration would like to see that changed.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

With a mandate to make the United States “energy dominant” and claiming the path to that dominance will be “through the great state of Alaska,” the Trump administration—with support from Alaska’s congressional delegation, the Alaskan state government, and two for-profit Native corporations, Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and Doyon Limited—is attempting to turn any land or water in Alaska’s Arctic that is deemed to have oil and gas potential into an extractivist technosphere. The proponents of extraction are ignoring ecological values, Indigenous food security and cultural values, the climate crisis, and the extinction crisis. Nothing is sacred. Nothing is off limits. It’s all “open for business,” as Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke famously told a cheering crowd at an Alaska Oil and Gas Association conference in Anchorage last year.Margaret Kriz Hobson, “With New Actions, Zinke Says Alaska Is ‘Open for Business,” E&E News, June 1, 2017, https://www.eenews.net/stories/1060055396.

What would an extractivist technosphere look like across Alaska’s Arctic?

In her pathbreaking report Broken Promises: The Reality of Big Oil in America’s Arctic, biologist-turned-conservationist Pamela Miller begins to describe it:

Prudhoe Bay and thirty-five other producing fields today sprawl across 1,000 square miles, an area the size of Rhode Island. There are more than 6,100 exploratory and production wells, 225 production and exploratory drill pads, over 500 miles of roads, 1,100 miles of trunk and feeder pipelines, two refineries, 20 airports, 115 pads for living quarters and other support facilities, five docks and gravel causeways, 36 gravel mines, and a total of 27 production plants, gas processing facilities, seawater treatment plants, and power plants.Pamela Miller, Broken Promises: The Reality of Big Oil in America’s Arctic, first published in 2003.

And those numbers have increased significantly since the report was published in 2003. If you take all that and repeat it across the entire North Slope of Alaska, add a road network and similar infrastructure placed offshore, and then overlay it all on top of a map like Alaska’s Arctic, you will have a visualization of what a complete extractivist technosphere might look like. Last year, the Alaskan state government offered a plan to build a “vast network of roads” across Alaska’s Arctic, with a justification from Governor Bill Walker that “a network of permanent roads would make finding and developing oil fields in the Arctic a lot easier.”Elizabeth Harball, “Alaska Hatches Plan for Vast Road Network across the Arctic,” Alaska Public Media, September 7, 2017, https://www.alaskapublic.org/2017/09/07/alaska-hatches-plan-for-vast-road-network-across-the-arctic.

What does it mean to actually develop an area?

To answer the ecological, cultural, technical, legal, and political aspects of that question, we turn our focus to a particular area: the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a transnational nursery of global significance and a place the Gwich’in people call “the sacred place where life begins.”

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The campaign to create the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge started in the early 1950s, and the campaign to defend it from oil and gas development has been going on since the Reagan administration first made a push to open it up in the 1980s. This coalitional and multigenerational engagement is the longest running environmental conservation and Indigenous rights campaign in the United States and an exemplary case of “long environmentalism.”Subhankar Banerjee, “Long Environmentalism: After the Listening Session,” in Ecocriticism and Indigenous Studies: Conversations from Earth to Cosmos, ed. Joni Adamson and Salma Monani (London: Routledge, 2016).

Last year, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act opened up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain to oil and gas exploration and development. Prior to the passage of that bill, Senator Lisa Murkowski chaired a Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing that laid the groundwork. Twelve witnesses testified (including co-author of this essay Lois Epstein) to elaborate on the important issues the Senate needed to understand prior to passing a bill. However, throughout the hearing, there were misrepresentations of the likely effects of oil and gas development. We elaborate below on four such key misrepresentations, focusing largely on the technological aspects relevant to discussions around the technosphere.

1. The Oil Industry’s Track Record in Alaska’s Arctic

“New technologies that are in place and are still coming online will ensure that responsible development does not harm the environment. … For over forty years now, Alaskans have repeatedly proven that we can develop safely and responsibly.”—Senator Murkowski, November 2, 2017

Oil and gas development in the harsh environment of the Arctic is inherently complicated and messy. Even the most experienced and best financed operators cannot ensure no spills of crude oil or other hazardous materials will occur. Nor can operators prevent all blowouts, because they may encounter unexpected or changing subsurface conditions that they have not adequately addressed. Additionally, there is always tension for oil companies between reducing costs and maintaining regulatory compliance, including safety and environmental protections.

A few recent significant spills and blowouts in the oil fields of Alaska’s Arctic include BP’s blowout in April 2017, which occurred due to thawing permafrost, a result of rapid Arctic warming; Repsol’s well blowout in the winter of 2012, which spewed approximately 42,000 gallons of drilling muds and took a month to plug due to frigid temperatures; and BP’s March 2006 pipeline spill of over 200,000 gallons, the largest crude oil spill to occur in Alaska’s Arctic oil fields, followed by a second spill in August 2006, resulting in BP’s shutdown of production in Alaska’s Arctic and bringing to light major concerns about systemic neglect of key infrastructure.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The state of Alaska completed a report in November 2010 that reviewed over 6,000 spills in Alaska’s Arctic from 1995 to 2009. Nuka Research & Planning Group, LLC, North Slope Spills Analysis: Final Report on North Slope Spills Analysis and Expert Panel Recommendations on Mitigation Measures, for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, 244 pp., retrieved November 1, 2017 from http://dec.alaska.gov/spar/PPR/ara/documents/101123NSSAReportvSCREENwMAPS.pdf (November 2010). The report showed there were forty-four loss-of-integrity spills each year,Ibid., p. 21. with a spill of 1,000 gallons or more nearly every two months.North Slope Spills Analysis: Final Report on North Slope Spills Analysis and Expert Panel Recommendations on Mitigation Measures, for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (Plymouth, MA: Nuka Research & Planning Group, LLC, 2010), https://dec.alaska.gov/media/7570/nssa-final-report.pdf. One year earlier, the Wilderness Society issued the second edition of its Broken Promises report. A. E. Gore, The Wilderness Society, Broken Promises: The Reality of Oil Development in America’s Arctic (2nd Edition), (2009). The Wilderness Society’s report shows a spill frequency of 450 spills each year during 1996–2008. The difference is that the state included only “production-related” spills and excluded toxic chemical (e.g., antifreeze) and refined product (e.g., diesel) spills, many of which are related to oil development, as well as spills indirectly related to oil production infrastructure, such as those from drilling or well-workover operations and from vehicles.

Recent spill rates have not decreased significantly. According to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation’s database, there were 169 reported spills between 2013 and 2018.See the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Spills Database Search website at http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/PublicMVC/PERP/SpillSearch. When taking spills of all types into account, however, the number rises to 1,551, which is about 310 spills per year, or nearly one per day.

2. The Size of the Development

“We meet this morning to consider opening a very small portion of Alaska’s 1002 Area … to develop just 2000 federal acres within it, about 1/10,000th of ANWR.”—Senator Murkowski, November 2, 2017

The 2,000-acre limitation in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act does not include all the infrastructure necessary for oil and gas exploration and development. In fact, infrastructure would sprawl across the 1.5 million-acre coastal plain. The named 2,000 acres include only the limited places where pipeline support posts touch the ground, not the vast areas traversed by pipeline infrastructure.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The first step in development is seismic exploration. Extensive aerial mapping conducted this year by geophysicist Dr. Matt Nolan shows tracks on the tundra from recent 3D seismic exploration just outside the western boundary of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It presents as a tight grid of 200 meters by 400 meters, what Nolan calls the “Arctic Checkerboard."Matt Nolan, “Detecting Tire Tracks in the 1002 Area with Fodar,” Fairbanks Fodar, July 1, 2018, http://fairbanksfodar.com/detecting-tire-tracks-in-the-1002-area-with-fodar. That checkerboard is not merely an eyesore that will remain for decades to come but also will have significant impacts on vegetation and hydrology. The federal government is proposing a similar 3D seismic exploration across the entire 1.5-million-acre coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, to begin this coming winter.Donald A. “Skip” Walker, “Seismic Testing in ANWR Will Have Major Impacts,” Anchorage Daily News, August 3, 2018, https://www.adn.com/opinions/2018/08/31/seismic-testing-in-anwr-will-have-major-impacts. The 2,000-acre footprint is a mere myth.

3. Probable Impacts on Caribou

“We will not harm the caribou who move through the area.” —Senator Murkowski, November 2, 2017

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is used with varying frequency by three of the four herds that calve in Alaska’s Arctic. The most consistent use is by the Porcupine Caribou Herd, which inhabits the refuge throughout the year, including using the coastal plain for calving, nursing, insect relief, and post-calving aggregation.J. R. Caikoski, “Units 25A, 25B, 25D, and 26C Caribou,” in Caribou Management Report of Survey and Inventory Activities 1 July 2012–30 June 2014, ed. P. Harper and L. A. McCarthy (Juneau, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2015). Calving grounds and other sensitive habitats can easily be disturbed, disrupting caribou use.

Studies of the Central Arctic Caribou Herd provide a cautionary tale about the possible effects of energy development within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. As oil development expanded from Prudhoe Bay, the portion of that herd using the calving grounds to the west of the development shifted south.S. A. Wolfe, “Habitat Selection by Calving Caribou of the Central Arctic Herd, 1980–95” (MS thesis, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, US); R. D. Cameron, W. T. Smith, R. G. White, B. Griffith, Central Arctic Caribou and Petroleum Development: Distributional, Nutritional, and Reproductive Implications,” Arctic, no. 58 (2005): 1–9; K. Joly, C. Nellemann, and I. Vistnes, “A Reevaluation of Caribou Distribution Near an Oilfield Road on Alaska’s North Slope,” Wildlife Society Bulletin, no. 34 (2006): 866–69; and E. A. Lenart, “Units 26B and 26C Caribou,” in Caribou Management Report of Survey and Inventory Activities. Those in the east, outside the main development areas, did not shift. Food availability was lower for development-exposed caribou,Sakakibara, “People of the Whales”; and B. Griffith et al., “The Porcupine Caribou Herd,” in Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries, ed. D. C. Douglas, P. E. Reynolds, and E. B. Rhode (US Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, 2002). which also exhibited lower calf body mass and birth rate.S. M. Arthur and P. A. Del Vecchio, Effects of Oil Field Development on Calf Production and Survival in the Central Arctic Herd (Juneau, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2009); Kriz Hobson, “Alaska Is ‘Open for Business”; and National Research Council, Cumulative Environmental Effects of Oil and Gas Activities on Alaska’s North Slope (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003). A review by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) concluded that there was no clear biological explanation for the shift in concentrated calving in the west, implicating oil development as its likely cause.Banerjee, “Long Environmentalism.”

In general, industrial roads and pipelines can alter caribou migratory movements.R. R. Wilson, L. S. Parrett, K. Joly, and J. R. Dau, “Effects of Roads on Individual Caribou Movements during Migration,” Biological Conservation, no. 195 (2016): 2–8. Females about to give birth or with very young calves tend to avoid or are less likely to cross roads and pipelines during the calving season.Banerjee, “Long Environmentalism.”

large

align-left

align-right

delete

USGS has also pointed out a number of reasons why responses to oil development may in fact be greater in the Porcupine Caribou Herd compared to the Central Arctic Caribou Herd.Banerjee, “Long Environmentalism.” One major factor is that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain is significantly narrower compared to the main calving range of the Central Arctic Herd further west, near Prudhoe Bay, leaving less room for shifts in space use. Another is that the expansion of development and the shift in Central Arctic Herd calving occurred during a period of relatively favorable environmental conditions. Future environmental changes, due to natural fluctuations (e.g., El Niño and La Niña cycles) or climate change, may reduce the ability of caribou to accommodate range shifts.

Retired federal biologist Fran Mauer, who studied the Porcupine Caribou Herd for more than two decades, has suggested that the herd uses the coastal plain, stretching across the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska and into the adjacent Ivvavik National Park in the Yukon, as one large birthing site and nursery. Which side of the border the caribou calve on depends on weather fluctuations, but they always go to the refuge coastal plain for nursing, even if they calve on the Canadian side. Mauer insists that any oil and gas development in the area will endanger the herd’s survival, and consequently also the way of life of the Gwich’in people.Subhankar Banerjee, “Drilling, Drilling, Everywhere … Will the Trump Administration Take Down the Arctic Refuge?,” TomDispatch.com, November 9, 2017, http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/176349.

4. Probable Impacts on Polar Bears

“We will not harm the polar bears whose dens can be protected.”—Senator Murkowski, November 2, 2017

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain provides the most important onshore denning habitat for polar bears in Alaska’s Arctic. Polar bears can be found on the coastal plain year-round.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service designated 77 percent of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain as critical habitat for polar bears, which are listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act.“Endangered Species Act Listing: Polar Bear,” United States Fish and Wildlife Service, last updated June 2017, https://www.fws.gov/alaska/fisheries/mmm/polarbear/esa.htm. The Southern Beaufort Sea polar bear subpopulation, which uses the coastal plain and barrier islands of the refuge, is currently in rapid decline, decreasing from just over 1,500 bears in 2006 to about 900 in 2010, or a 40 percent loss.E. V. Regehr, S. C. Amstrup, and I. Stirling, Polar Bear Population Status in the Southern Beaufort Sea ( Reston, VA: US Geological Survey, 2006); and J. F. Bromaghin et al., “Polar Bear Population Dynamics in the Southern Beaufort During a Period of Sea Ice Decline,” Ecological Applications 25, no. 3 (April 2015): 634–51. Recent research has found that decreasing sea ice due to climate change has increased the use of terrestrial habitats by these polar bears, including for denning on the coastal plain.T. C. Atwood et al, “Rapid Environmental Change Drives Increased Land Use by an Arctic Marine Predator,” PLoS ONE 11(6) (2016): doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155932.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In light of the above, there are great concerns about the additional impacts oil development would place on polar bears in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge coastal plain. Any oil development within the refuge, including seismic exploration activities, which have been shown to disturb polar bears from maternity dens,National Research Council, Cumulative Environmental Effects, 157. will increase the potential that onshore bears will be disturbed by human activities as well as the potential for human–polar bear conflicts.S. C. Amstrup, “Human Disturbances of Denning Polar Bears in Alaska,” Arctic 46, no. 3 (1993): 246–50.

Defending Alaska’s Arctic

Since the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December 2017, the Department of the Interior has been working at breakneck speed to get an environmental impact statement in place so it can offer lease sales by the summer of 2019. Critics point out that it normally takes three to five years to properly evaluate the environmental impact of a project of this magnitude.

Polls conducted by Yale in 2018 show that 63 percent of Americans oppose drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.Jennifer Marlon et al., “Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2018,” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, August 7, 2018, http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us-2018. The public all across the country care about this issue, have done so for decades, and yet the Department of the Interior held only one hearing on oil and gas development in the coastal plain outside of Alaska, which was in Washington, DC. It was held on a Friday afternoon in summer, which undoubtedly contributed to minimizing participation from the public and the media. On August 9, 2018, the cooperating agencies were given a nearly 600-page draft environmental impact statement and only a week to review and comment on it—significantly less time than is normally granted for such a monumental and consequential task.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The federal government is fast-tracking the process, resulting in inadequate consultations with Indigenous Peoples and not allowing the public to meaningfully participate. In so doing, it is setting itself up for inevitable legal challenges.

To understand and begin to address the Trump administration’s reckless Arctic policy, Subhankar Banerjee, co-author of this paper, convened the three-day national symposium The Last Oil, at the University of New Mexico in February 2018. Following the symposium, Banerjee and historian Finis Dunaway co-wrote and co-organized a letter campaign, Scholars for Defending the Arctic Refuge, which was endorsed by more than 500 scholars from twenty countries representing more than forty academic disciplines. Banerjee and Dunaway also testified at the public hearing in Washington, DC, and submitted the letter as part of the public scoping process on June 19, 2018. The letter opened with enumerating the key threats:

The Arctic Refuge may seem far away to many, but its Coastal Plain is one of the most significant biological nurseries in the Circumpolar North. Opening the Coastal Plain to fossil fuel exploration and development would endanger this nursery. It would violate human rights and jeopardize the food security of the indigenous Gwich’in people of the US and Canada. It would have detrimental effects on the health and social life of the indigenous Iñupiat people who live nearby. It would also contribute to further warming of the already rapidly-warming Arctic—an action that would affect the whole earth, as the Arctic is a critical integrator of our planet’s climate systems.Subhankar Banerjee and Finis Dunaway, “Scholars for Defending the Arctic Refuge,” June 19, 2018, The Last Oil, https://thelastoil.unm.edu/scholars-for-defending-the-arctic-refuge.

Even as the Trump administration is pushing as hard and fast as possible to usher in a reckless extractivist technosphere all across Alaska’s Arctic, a US-Canada binational coalition of Indigenous human rights and environmental conservation organizations are pushing back just as hard. They are working to defend the transnational ecosphere, including the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It is a campaign for multispecies justice, acknowledging that the concerns of human and nonhuman lives are intimately entangled.Subhankar Banerjee, “Resisting the War on Alaska’s Arctic with Multispecies Justice,” in “Beyond the Extractive View,” ed. Macarena Gómez–Barris, special issue, Social Text Online, June 7, 2018, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/resisting-the-war-on-alaskas-arctic-with-multispecies-justice. These activists say, “The fight for Alaska’s Arctic has just begun.”