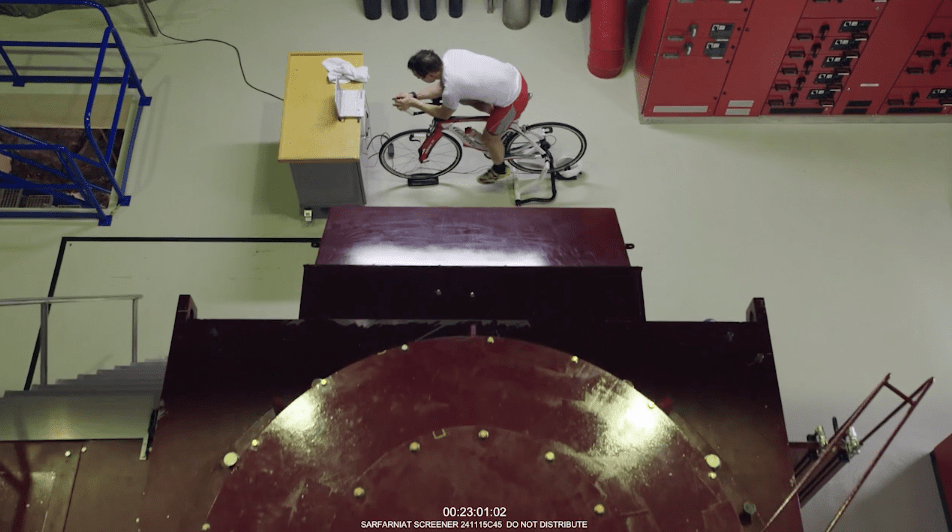

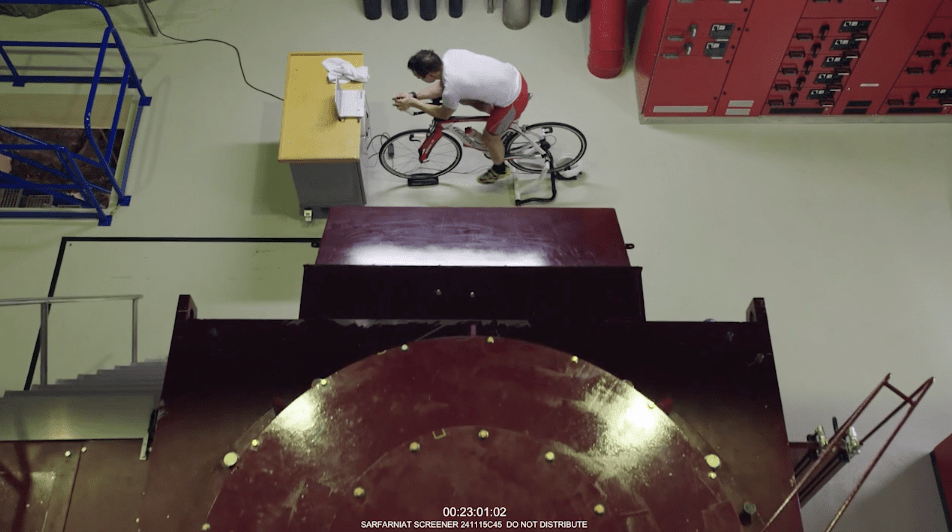

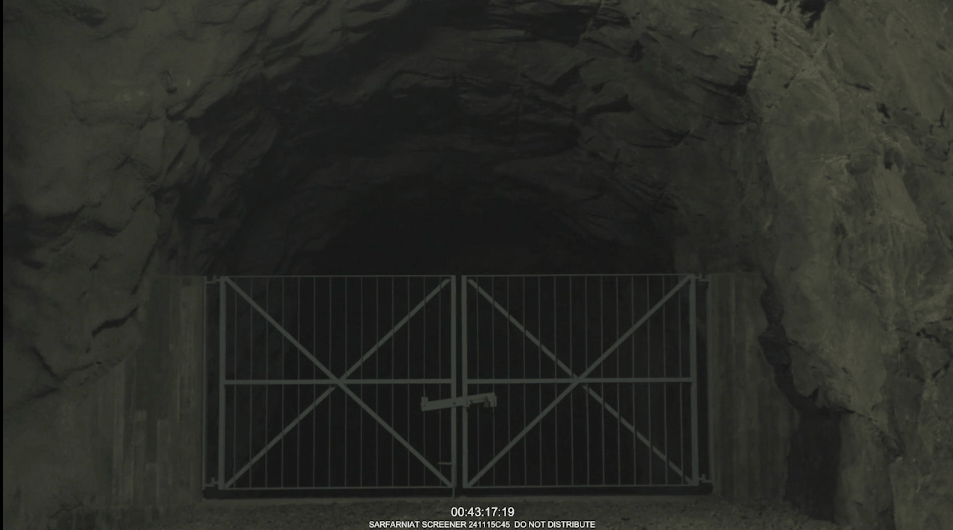

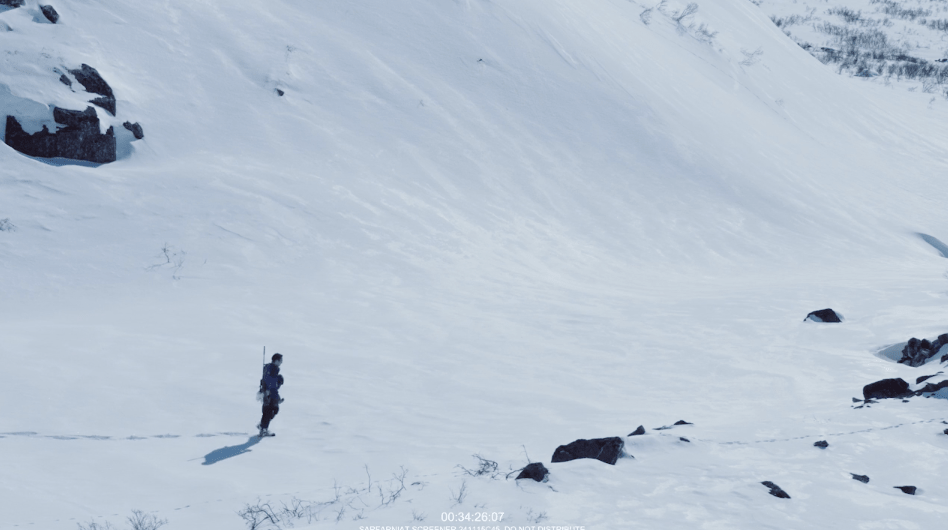

Still from Sarfarniat (The Hunters of the Current), 2015, directed by Hunter Snyder

Living Arctic Infrastructures

How do Arctic infrastructures “live”? How does their extractive and appropriative logic do service to a rapidly changing world to come? Through both his own ethnographic studies and a documentary about workers at a hydroelectric power plant located on the far edge of Greenland's ice sheet, communication and cultural scholar Rafico Ruiz stresses the sets of relations created between the energetic imaginaries of large-scale technical infrastructures and global environmental change.

In the summer, when the pack ice has disappeared, you arrive at Nukissiorfiit’s Buksefjord hydroelectric power plant by boat. On the far edge of Greenland's ice sheet, at the end of the Kangerlussuaq Fjord, the plant supplies Nuuk, the country’s capital, with forty-five megawatts of power—snowmelt-derived energy that is translated into Netflix streaming, hot sauna air, and glowing phosphorescence from the streetlamps that trace the city’s streets.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

As with much of the infrastructure across southern regions, energy in Greenland likewise signals how environments and their extensions through infrastructure can be put to “work” in the service of enabling the day-to-day lives of humans. “Infrastructure,” ubiquitous as the term has become, really designates “a process of relationship building and maintenance.”Ashley Carse writes, “I emphasize infrastructural work—a term used by science, technology, and society scholar Geoffrey Bowker—to foreground the variety of organizational techniques (technical, governmental, administrative, environmental) that create the conditions of possibility for rapid and cheap communication and exchange across distance. As scholars have shown, infrastructure does not refer to any specific class of artifact, but to a process of relationship building and maintenance.” Ashley Carse, Beyond the Big Ditch: Politics, Ecology, and Infrastructure at the Panama Canal (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 11. Carse’s efforts at extending Susan Leigh Star’s and Karen Ruhleder’s foundational work toward its ecological dimensions highlights how infrastructure and environment making are often one and the same process. It designates how moving melt water can be put into relation with the urban lives of Greenlanders in Nuuk. Infrastructural relations aren’t about establishing commensurate values between a given environment and the provision of a utility; rather, these relations, particularly as they’re grounded in a place such as Nuuk, are predicated on the forms of life they enable or constrain.

How do Arctic infrastructures “live”? That is, how do they respond to their surrounding material and ecological conditions, which are currently in dramatic flux due to global warming, while also enabling some forms of life and not others. Living Arctic infrastructures is both a condition and an open-ended process—they encompass melt water that is always moving downward, following gravity off the fjord, and a forty-five megawatt threshold that establishes a definite limit on Greenland’s variable energy imaginary.Greenland’s energy imaginary and the material landscapes on which it relies are currently in flux. Nukissiorfiit, the national utility company, is aiming to expand its hydropower capacity with development projects across the island.

*

The Buksefjord hydroelectric power plant was completed in 1993. It is a “Norwegian-style” plant, which means that the turbine hall and aqueduct are located underground, dug out of the steep walls of the fjord. The lake that provisions the plant is several kilometers inland. One outcome of this style of construction is that the plant gives the impression of existing on its own at the end of the fjord. Only the high-voltage transmission lines that seem to glide out from the plant’s facade, making their way toward Nuuk, suggest the longer chain of infrastructural and environmental relations that connect the plant to Kang Lake and, further inland, the ice sheet.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Infrastructures, following the theoretical work of foundational ethnographer of infrastructure Susan Leigh Star, really are both “ecological” and “relational.” In this regard, the material politics that infrastructures embody point to the distributed constituencies, often local and agonistic in decolonizing contexts, that such seemingly mundane and invisible pipes, road networks, and telecommunications systems subtend. “The image becomes more complicated,” Star writes, “when one begins to investigate large-scale technical systems in the making, or to examine the situations of those who are not served by a particular infrastructure.”Susan Leigh Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” in American Behavioral Scientist, no. 3 (November 1999): 380.

The Buksefjord hydroelectric power plant, seen through the optic of reduced snowmelt precipitated by global warming, is a “large-scale technical system” that is in many respects still in the process of being made. While it has an engineered production limit of forty-five megawatts, the largest in the country by a significant measure, its malleability resides in its symbolic and cultural valences that enter into relation with the provisioning of energetic water through unpredictable and less frequent melting events. Under the conditions imposed by global warming, which, as we know, are keenly amplified in the polar regions, the water that steadily flows into the plant’s spinning turbines has become a variant of itself—as if its own sense of matter has come to be replicated by a carbon-derived solute. The binding together of ecologies and infrastructures, as Ashley Carse and other scholars have shown, makes the infrastructural relations established by hydroelectric plants into “temporary lines across active environments that erode, rust, and fracture them.”Carse, Beyond the Big Ditch, 5. We are thus only and always left with temporary infrastructures and active environments. Indeed, in the Arctic in particular, these relations possess temporal markers that pivot around just such ethical horizons established by global environmental change—such as how water-as-energy comes to be coupled with the plant’s disrupted local hydrological cycle.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

This ethical horizon is one that is justifiably distant from government and corporate boardrooms across the island of Greenland. After all—and as Greenlanders know all too well, given their inhabiting the temperate South’s spatial and temporal climate change future—infrastructural life is really all that remains. I came to see this dimension of the plant only after my initial visit there in June 2017. The artifact that enabled this shift is a remarkable unreleased ethnographic film called Sarfarniat (The Hunters of the Current), assembled by Hunter Snyder, a PhD student in the Ecology, Evolution, Ecosystems, and Society graduate program at Dartmouth College. The film largely follows the day-to-day work life of Jens and his colleague Jonas at the remote hydroelectric station in Western Greenland. Workers at the plant are brought in for two-week shifts, by helicopter or boat, depending on the ice conditions, and ensure the steady flow of electricity to Nuuk.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

What is remarkable about Snyder’s film is how it slowly builds a silent portrait of Jens as a plant worker who is oddly in tune with his everyday environment. He attends to the needs of the plant, checking gauges and valves and cleaning surfaces, while also maintaining his own sense of physical and mental well-being. In many ways, I see Jens as a sort of allegorical figure that can allow us to understand how we can live with the mundane, everyday realities of global climate change. In his world, you make do with the environment you inhabit—that is, you run and cycle up and down the plant’s access tunnel; you maintain a sense of physical and mental readiness for forays out onto the land and water to hunt for what you can. Much like the fast and, for now, steady water that flows through the plant to create the necessary electricity for Nuuk’s urban living, Jens’s work life is regulated by the variable flow of snowmelt. By the film’s end, it almost seems as if Jens and the hydroelectric station are interchangeable entities, both generators of energy out of the environment.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The film as a whole serves as an ideal allegorical embodiment of what I think of as the condition of “earth optimism.” This is not a condition of regress and retreat to some sort of pre-climate-change world of balance. Rather, earth optimism, as represented in the film, is a matter of learning to live within the machines that we as humans have created. That the Earth in the Anthropocene has become one such machine is a fact of life. As Jens does, it is up to us to devise the day-to-day procedures that can build toward a mundane optimism in the Earth that surrounds us. A wonderful shot from the film lingers on a small boat kept in a recess of the plant’s access tunnel. At first sight it makes for an odd image—a boat underground? Then you realize that the boat, and the tunnel itself, are there should the controlled flow of water break down and a disastrous flood ensue. The image of the lifeboat tweaks how we see Jens’s life at the plant and, by extension, its allegorical significance for our day-to-day life with climate change. Learning to live in the machine we have built is to learn to live with dangerous water (sea-level rise), uncertain energy (snowmelt), and a range of climate effects that are human induced. But it is also a matter of not losing sight, as Jens doesn’t, that there is an outside to the Earth machine—that there is concealed life in the snowy margins of the fjord.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

“Infrastructure is by definition future oriented; it is assembled in the service of worlds to come,” Deborah Cowen writes. “Infrastructure demands a focus on what underpins and enables formations of power and the material organization of everyday life.”Deborah Cowen, “Infrastructures of Empire and Resistance,” Verso blog, January 25, 2017, http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance. How to live with and as Arctic infrastructures? Through both condition and process. These are the worlds to come. And yet it is essential to recognize that the futures defined by Greenland’s infrastructural life don’t discount or set aside long-standing Indigenous land- or water-based conceptions of self-definition. Rather, as fishers and hunters in Greenland will readily relate, infrastructural relations around energy and ice, to power Ski-Doos, generators, and satellite phones, are part of their lives and livelihoods.For an outstanding treatment of this relationship across the circumpolar world, see Igor Krupnik, Claudio Aporta, Shari Gearheard, Gita J. Laidler, and Lene Kielsen Holm, eds., SIKU: Knowing Our Ice: Documenting Inuit Sea-Ice Knowledge and Use (New York: Springer, 2010).

The Buksefjord hydroelectric power plant is a marker of an emergent form of extraction taking place at the environmental meeting points between warming atmospheric events and the now uncertain phase states of matter such as post-climate change water. It is an extractive logic that is not unproblematically bound to its time and place—whether Greenland’s increasingly unpredictable accumulation of snowpack or the downward trend of the ice sheet. These modes of environmental characterization almost make such practices of extraction seem inevitable: melting ice moving downhill is a call to governmental energetic imaginaries. In some respects, this extraction is part of the ontological conditions of earth optimism, a state wherein open-ended melting into an unforeseeable future is normalized and thus made into a potential infrastructural relation. Is this a matter of letting our disrupted Arctic infrastructures “live”? Anthropogenic influence, as Michel Serres has it, tends to operate on the basis of “appropriation through pollution,” and the Arctic has now come under its warm and suffocating breath.See Michel Serres, Malfeasance: Appropriation through Pollution, trans. Anne-Marie Feenberg-Dibon (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011).

To live Arctic infrastructures and to track how they themselves live is to set this condition and process, as a manifestation of global environmental change, into infrastructural chains of causation and accountability. After all, the CO2 may not be straightforwardly “rising,” but it is following the meteorological contours of the Earth toward the Poles. In Greenland and elsewhere in the circumpolar world, the new settler is climate change. Living Arctic infrastructures are the means by which to uncover the set of relations that can start to make it accountable.