1. WaveNet: On Machine and Machinic Listening

Guest curator Stefan Maier introduces this dossier by discussing WaveNet, Google's recently released speech synthesizer that is capable of both remarkable realism and abjection through applied machine listening. Arguing that technologies of synthetic sensation might have as much to do with the novel possibilities afforded by artificial intelligence as they do with the assumptions that underlie technical activity itself, Maier also acknowledges that such insights are not without significant historical precedence. In particular, this editorial looks to Maryanne Amacher's media opera Intelligent Life (1980–) and George Lewis's work in computer-human interaction as anticipating such problematics decades ago.

On September 8, 2016, Google released its highly anticipated speech synthesizer, WaveNet.DeepMind: “WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio” (https://deepmind.com/blog/wavenet-generative-model-raw-audio). Heralded as a groundbreaking technology in speech synthesis and artificial intelligence, it models and subsequently generates virtual speech with stunning accuracy. As was demonstrated at a recent Google keynote lecture, which featured recordings of WaveNet ordering food and booking appointments for a client, the tool easily passes the famous Turing test.See “Google’s AI Assistant Can Now Make Real Phone Calls,” YouTube video, 3:57, posted by Mashable Deals, May 9, 2018 (https://youtu.be/JvbHu_bVa_g). Since the dawn of computer-human interaction, researchers have long dreamed of a tool that might seamlessly interface computers with humans using verbal communication. It appears as though that future has arrived.

What underlies WaveNet’s remarkable functional capacities for speech is applied machine listening. In stark contrast to the largely mechanistic computational tools of decades past, machine listening actively infers sense from machine sensation. Where signal-processing tools hear, the synthetic brain-ear complexes of this class of AI listen. As such, machine listeners are designed to understand sound through the constitution of an artificial ‘listening mind.”

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In the case of WaveNet, a neural network was trained on a large data set recorded from human speakers. After listening to countless hours of real-world speech, the network gradually inferred a deep structural understanding of human utterance. By drawing on disparate timescales, multiple categories of analysis, and, most of all, the computer’s capacity for high-order abstraction, a complex statistical model of speech was constructed via WaveNet’s listening. This model represents the operative core underlying WaveNet’s unprecedented abilities: the dynamism, subtlety, fidelity, and realism of its speech is facilitated by this deep structural knowledge. Accordingly, by drawing on the complexity of its statistical inference, WaveNet can perform seamlessly in even highly ambiguous human-computer interactions.“Google’s AI Assistant Can Now Make Real Phone Calls.” See the the conversation between WaveNet and an ESL restaurant employee.

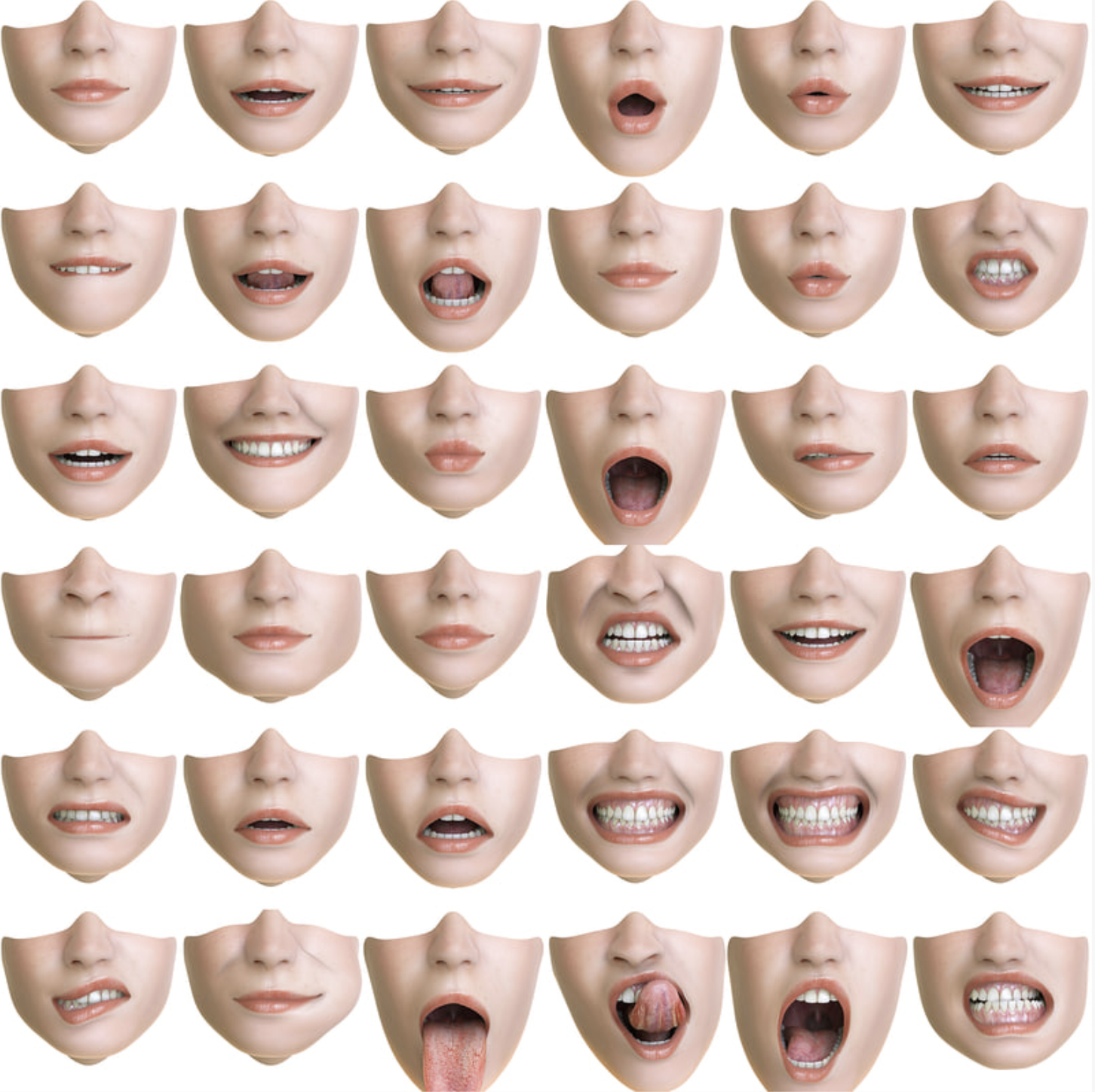

While it is often assumed that the abstract models at the heart of such technologies correspond to the real-world knowledges held by their creators, this is not necessarily the case. Despite WaveNet’s functional utility, the technologists who developed it have noted a surprising by-product. Remarkably, when removed from the circumstances for which it was designed, WaveNet can “speak” on its own.DeepMind: “WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio.” See the subsection “Knowing What to Say.” In lieu of a human interlocutor to converse with, WaveNet can generate speechlike audio that does not correspond to any known language. Here, one speech element follows the other in a fluid yet irregular fashion: stuttering and jerking phonemes start and stop, unpredictably interrupting one another. Even stranger, speechlike sounds are accompanied by the irregular clicking of digital teeth and smacking of synthetic lips.Ibid. See recordings. We are left to wonder: What human mouth might produce such uncanny abjection?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

When listening to WaveNet’s accidental speech, I am reminded of Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “There Are More Things,” in which the protagonist wanders into the house of one Max Preetorius, only to find incomprehensible pieces of furniture: “vertical ladders with wide irregularly spaced iron rungs” and “a U-shaped operating table, very high, with circular openings at the extremes” that is “perhaps a bed” for some horrible creature.Jorge Luis Borges, “There Are More Things,” in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley. London: Penguin Books, 1998. Disturbed, the protagonist moves to leave only to hear “something heavy, slow and plural” move behind him. The story ends. In Preetorius’s house, “no insensate forms … corresponded to any conceivable use,” but through the clarity of abstract shapes and proportions—under the analytic clarity of “pitiless white light”—a strange anatomy is revealed obliquely, leaving the protagonist with a sense of “revulsion and horror.” Similarly, WaveNet’s abject speech suggests an uncanny synthetic mouth: one that distorts the physiognomy it was designed to reflect through “pitiless” algorithmic codification and inhuman rationality.

When removed from the circumstances that provoke streamlined behavior, WaveNet generates its speechlike sound by drawing directly on the abstract principles underlying its statistical modeling. Paradoxically, it is the same mechanism that facilitates both abjection and utilitarian function: a deep structural account of speech inferred by a neural network. However, it is only when WaveNet is directed at no one in particular that it speaks without regard for language—without regard for meaning making. Instead, in such situations it blindly follows statistical inference without circumstantial consideration. Granted, WaveNet’s nonsensical speech still assumes some warped semblance to its human counterpart. One may even speak of a certain phonetics or syntax here. Accordingly, to speak of WaveNet’s speech as “autonomous” is to indulge in undue romanticism. But, crucially, its behavior is severed from any demands of utility. Instead, WaveNet’s accidental speech follows statistical abstraction unhinged from the humancentric limits so often placed upon emergent technology.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

***

In the technosphere, the “human” sensory apparatus is augmented and projected beyond its biological bounds through instruments for artificial sensation. Sensors, cameras, and microphones are used by machines to augment human sensation through the artificial modeling of touch, vision, and listening. With recent advances in computing—in particular, with the current Cambrian explosion of artificial intelligence—this transformation has approached levels of complexity, resolution, and scale formerly thought impossible. However, this radical expansion of sensation has had unexpected results. Despite continued efforts to design such tools within the parameters of the human sensorium and cognition, integration between human and machine sensation continues to evade algorithmic determination. Instead, when considering contemporary technologies of artificial sensation, we are faced with the recognition that these instruments might sense far differently than humans do—that there might be a profound disparity between utility and the underlying operational capacity when considering these tools.See Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Minneapolis: Univocal, 2017, pp. 247–60. Here, despite consistent anthropomorphic projection, we are faced with modes of sensation that both differ from and amplify certain facets of what is often presumed to be immutable and given.

Accordingly, the uncanny reflections of the human offered by machine sensation might have as much to do with the technicity of sensation as they do with the normative self-understandings that steer technical activity itself.

This tendency is of particular relevance when considering machine listening specifically. Inspired by the mechanisms underlying human audition, machine listeners perform intelligent operations on audio through the computational imitation of human perception and cognition. Here, “naturalized” conceptions of human listening are used as templates to endow computer audition with capacities projected to simulate our own. The psychoacoustic, cognitive-scientific, and musical knowledges thought to underlie the human auditory system are preprogrammed into the listening capabilities of this class of AI.This is perhaps most obvious when considering the use of auditory scene analysis (ASA) in machine-listening software. ASA explains processes by which the human auditory system organizes sound into perceptually meaningful elements. Through computational modeling—literally named computational auditory scene analysis—researchers attempt to ensure that the computer separates and subsequently organizes sounds in the same way that human listeners do. Yet, as is evidenced by WaveNet’s accidental speech, even despite significant measures taken to ensure that machine listening corresponds to human listening, the inner workings of the artifactual ear do not necessarily behave as planned.

In light of these observations, this dossier proceeds from the contention that the advent of synthetic listening might profoundly disturb the sense we have of contemporary aurality. The primary ramifications of this are twofold. On the one hand, the recent rise and diversification of machine listeners insists that we critically assess what implications such technologies might have for our own listening. When “naturalized” conceptions of the human are externalized through technology only to project elsewhere than anticipated, what does this tell us about the foundations that underlie such conceptions? What are the implications for these foundations when faced with the disparity between self-portraiture and technical operation? Might this disparity show that mutability underlies what we had initially assumed to be essential? On the other hand, with the advent of machine listening, we are faced with the recognition that listening might not exclusively belong to the human after all. Accordingly, if machines listen differently than we do, how might we characterize such listening? Here, what is proposed is the prospect of a certain “machinic listening”—a class of listening relations unique to specific technologies. This dossier wagers that if we look beyond anthropomorphic projections and tried-and-true utilitarian accounts of technology, some form of machinic alterity might be identifiable. As such, it positively appraises the neo-Copernican implications of machine listening and simultaneously readily invites the revision of normative values that inform contemporary aurality.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Though this dossier points toward hitherto unexplored potentials contained specifically within contemporary computer audition, it recognizes this situation is not without historical precedence: technical objects have always had a life parallel to the narratives within which they operate, and they have always had unexpected import. Accordingly, this dossier reflects on two specific moments of that history. Firstly, it recognizes composer, improvisor, and musicologist George Lewis as visionary in anticipating and articulating such problematics in his work with musical computing. In particular, we focus on Rainbow Family (1984), a pioneering composition that employs proto-machine-listening software to facilitate improvisatory human-computer interactions. Generating both complex responses to live musicians and independent behavior arising from the computer’s internal constitution, Rainbow Family is a prescient work that demonstrates not only that novel musical expression might be uncovered at the threshold of humans and computers, but, furthermore, that the exploration of such a threshold opens onto epistemological implications that parallel the problematics foregrounded by this dossier. Most importantly, Rainbow Family concretizes a central paradox underlying technology’s oscillation between (technical) object and (projected) subject. Here, it is precisely the computer’s slippage between these terms where Lewis articulates the technopolitical stakes underlying his work with intelligent machines. As Lewis explicitly asks in a 2013 lecture: “Does this [ambivalence between subject and object] not recall the American Black slave who sat no less provocatively and no less discursively on that very boundary?”See “Why Do We Want Our Computers to Improvise?,” Vimeo video, 1:15:00, posted by Monash Arts, November 5, 2013 (https://vimeo.com/78692461). Strongly echoing Fred Moten’s iconic opening to In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition—that “the history of Blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist”—Lewis articulates that the challenges posed by technology to the given “human” might be most productively allied with the emancipatory efforts of those who have been historically excluded from its categorical bounds. Or, going in another direction, that the possibilities afforded by inhuman technical operation might be most readily recognized and employed by subjects who have never been “human” in the first place.See Nina Power, “ Inhumanism, Reason, Blackness and Feminism,” Glass Bead, 2017 (http://www.glass-bead.org/article/inhumanism-reason-blackness-feminism).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In parallel with Lewis, this dossier also looks to the late work of the American composer Maryanne Amacher. In particular, it identifies Amacher’s unrealized work Intelligent Life (1980–) as a crucial departure point for such a line of inquiry. Conceived as a “media opera” in the form of a televised mini-series, the project was Amacher’s attempt at a populist work that would bring together the composer’s pioneering research into psychoacoustics, novel sound spatialization impressions, and multimodal listening. Ultimately, however, Intelligent Life was never developed beyond a detailed project description and a script for the pilot episode. Straining toward the future of possible listening as always, Amacher set Intelligent Life in an imagined 2021, when computationally augmented listening is industrialized and produced on a mass scale. The series was planned to follow and dramatize the developments of sound technologists and computational neuroscientists at Supreme Connections LLC, an institute for advanced augmented-listening research and application. From programs that model hearing through nonmammalian ears, to the artificial simulation of alien atmospheric conditions (of the Cambrian period or on the surface of Mars, for example), to listening “scores” that modulate between such disparate computational models,“There is a great demand for listening scripts. … Most popular are ‘Modulating Auditory Dimensions’ scores, which transform from CATERPILLAR to MOTH to BUTTERFLY to WHALE to SHRIMP, and so on, to other atmospheric dimensions.” Amacher used Supreme Connections as a platform for imagining the futures of computationally aided listening. Of particular interest is the institute’s “classified and most sensitive top secret PROJECT BEULAH.” Not only modeling the conditions of listening but the movement of the listening mind itself—that is, the “coding of the flow of neural pathways”—BEULAH seems to speak to the future that this dossier seeks to explore. As a reappraisal of Supreme Connections LLC, this dossier elaborates such a speculative project and compares the reality of “machinic listening” that we face today with Amacher’s singular vision of listening futurity.