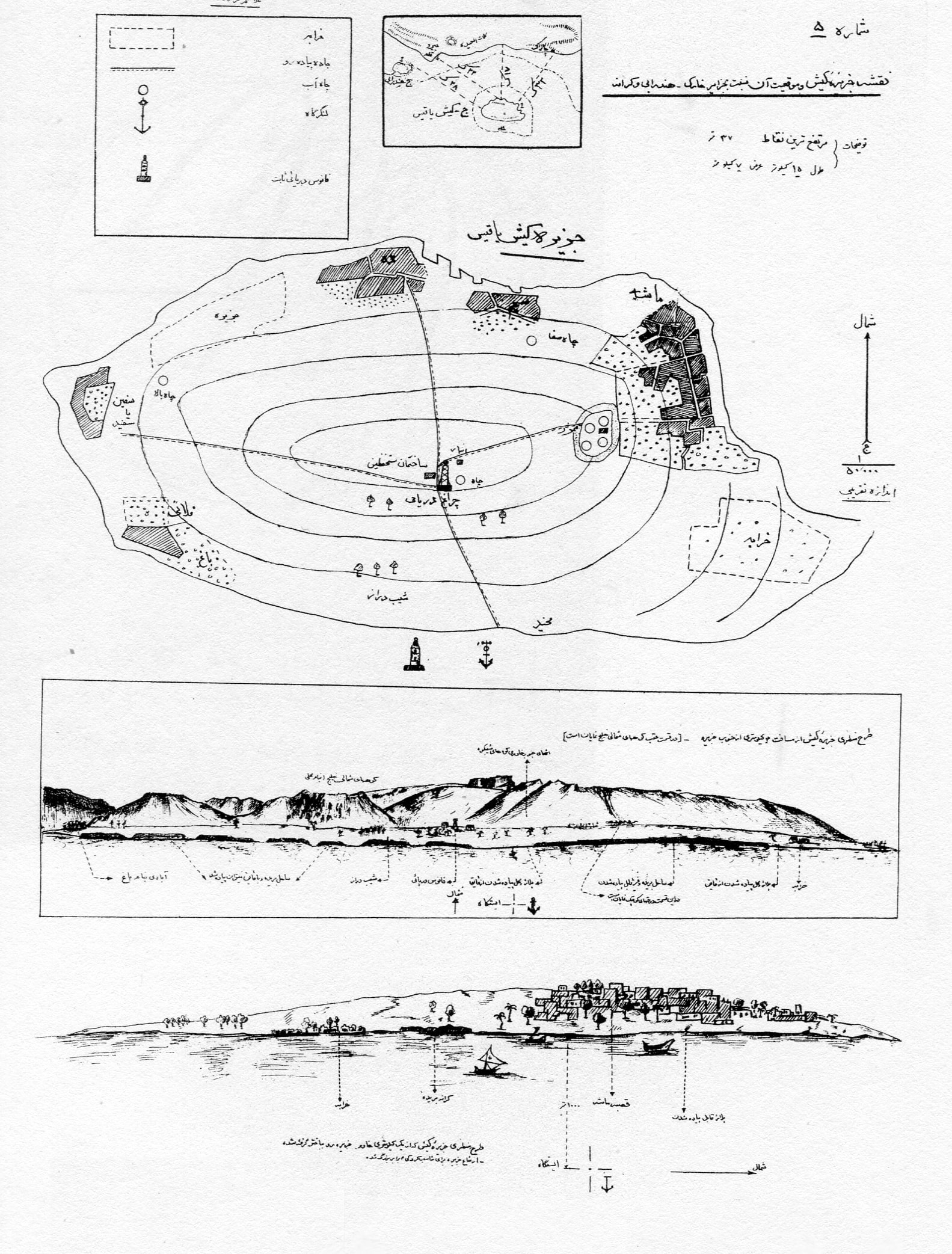

Source: Eckbo, Dean, Austin, and Williams and Mercury consultants

Kish’s first master plan, 1973, aerial perspective depicting the resort sector.

Kish, an Island Indecisive by Design

The Iranian island of Kish, due to its particular geographic location in the Persian Gulf, exemplifies how territorial separation can lead to political and economic hubris in the form of a globalized free-trade zone. Narrating its storied history, artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Barak Afrassiabi explore the strange role of this island as a designated place of exception in reality and imagination.

It was midnight, July 25, 1966, misty and very humid. A ship had unloaded its cargo at Shahpour port in the Persian Gulf and was heading homeland for Greece. Drifting off course, the ship became stranded just off the coast from Baghoo, the village on the island of Kish – so close to shore, in fact, that it could easily have run aground on the island. One of the villagers once told me that for seven nights the ship’s lights lit up the coastline and nearby village, which in those days didn’t have electricity. Just a boy then, he brought melons to the ship’s crew in exchange for canned fruit. On the eighth night, the ship ran out of fuel, its lights dimming and finally going out. Much work was done to tow the ship back into deeper waters but it only moved a few centimeters.

Today the ship has completely rusted over. Every time I happen to stop by, it seems as if it has been pulled a little further into the Gulf. In reality, it is the coastline that’s slowly wearing down into the sea. For forty-five years, the ship has stubbornly watched the island. Tourists come from all over Iran to view it silhouetted against the setting sun. With time, it has merged with Kish’s tropical sunset. I believe that Kish’s modernity began at midnight on July 25, 1966, when the steamship stranded off its coast. The marooned ship prophesied what would become Kish’s awry odyssey along the map of the modern world.

A Brief Introduction

For a long time Kish was a forgotten island in the Persian Gulf, left to its destiny and deprived of the riches and advancements that the northerly parts of Iran were enjoying. The islanders provided for themselves through fishing and unsteady farming – but most of all by importing illegal goods from neighboring countries across the Gulf. In the island’s first official census in 1956, the population numbered a mere 760. This was less than half of the population registered six years earlier by the geographic department of the Iranian national army. Since then, poverty had forced people to migrate to the countries on the south of the Persian Gulf. Permissive trade and customs regulations and the ease of traveling had turned the Arab sheikdoms into a true “free-trade zone,” which lured many people away from Kish and other southern parts of Iran. In 1955, when visiting Iran’s ports in the Persian Gulf, the newly appointed customs CEO also stopped at Dubai’s free-trade port. He was impressed by its many facilities. Two years later, when he was Minister of Customs, he promised to establish a free zone in Iran’s southern ports as well. However, this did not happen straight away; that is, not until the political scene in the neighboring Arab countries changed did the authorities in Iran really begin to take any notice of Kish Island.

The nationalization of the Suez Canal by Egypt in 1956 and the July 14 Revolution two years later that overthrew the pro-Western monarchy in Iraq, had heightened Pan-Arab sentiments. Radio signals from neighboring states, instigating Arab nationalism, were reaching Iran’s Arabic-speaking south, including Kish. They often criticized the Iranian government for allying with “Western imperialism” and discriminating against its Arab minorities. This alarmed the Shah and made him rethink the policies regarding the southern part of Iran. Still, only a decade later, a plan was drawn up for Kish: it was to become a “modern” and “progressive” destination for an exclusive brand of tourism. The government’s plan was to develop the island into an international tourist- and free-trade zone that would attract the wealthy elites from the oil-rich Arab sheikdoms as well as from the West. In 1968, Kish was officially designated a free-trade zone; and to cut out any competitors, all plans to turn existing trade ports into free zones were cancelled.

The first structure erected on Kish was the Shah’s palace. He had decided that the island should be an exclusive resort where he would spend the winter with his family and receive guests.

The island’s association with the royal family undoubtedly highlighted its allure and granted it geopolitical significance. It was only natural in this light that the royal family hosted its high-toned inauguration, for which a select group of international guests were flown in with a Concorde airliner. The date was October 29, 1977; the protests preceding the revolution on mainland Iran were slowly getting underway.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

I once calculated that if I were to walk from where the Greek ship was stranded all the way to the opposite side of the island, in a straight line exactly aligned with the ship’s axis, I would end up at a curved tip on the northeastern shore, renowned for being the best place on the island from which to view the sunrise. The development of the resort began right at the foot of this shore. With its sandy beaches, it was considered the best place for leisure and entertainment. The site for the proposed resort was already inhabited, and this meant it had to be “evacuated” before the resort could be built. The spot had been the administrative heart of the island and home to its largest village, Masheh, the Farsi word for “trigger.” In 1971, a governmental entity called The Kish Development Organization (KDO) was established to manage the new developments on Kish.The budget for the KDO was provided by the Development Bank (Bank-e Omran) and the National Intelligence and Security Organization (SAVAK). KDO first built another village farther to the west, adjacent to the existing village of Saffein, and moved the 700 inhabitants of Masheh there, mostly against their will. The new village became New Saffein, and Masheh was renamed Old Saffein.

Walking through New Saffein is a truly strange experience. The architects have painstakingly tried to simulate, in both use of materials and design, the features of vernacular architecture and planning typical of southern Iran, as was found in Old Saffein. In an information booklet that accompanied the 1977 official unveiling, handed out to foreign visitors, New Saffein is described as a village displaying the “genuine traditional lifestyle” of the native inhabitants of Kish as it had been during the time of Marco Polo.

Now, decades after Old Saffein became New Saffein, the village feels both old and unfinished. It’s old, but not necessarily because of the traditional appearance of the architecture. The continuous re-appropriation of the buildings by villagers, to adjust them to their needs, has given the village both a ruinous and an unfinished appearance. The architecture of New Saffein is exhausted, it is an “old building site” born out of an initial architectural misplacement. The houses in Old Saffein had high walls that both guaranteed privacy and cast long shadows across the narrow alleys during summer. The angle at which the houses were built was designed to create a network of shade throughout the village, but also to direct the course of the breeze coming in from the sea. But in New Saffein, the walls – built of concrete and covered with plain mortar to make them seem old – have been made lower around the courtyards. This has been done to make it easy for tourists to peek into the houses. But in most cases the residents have made the walls higher with materials that are clearly distinguishable from those originally used. And where the streets were made too wide, they have used corrugated steel or other structures to create the necessary shade

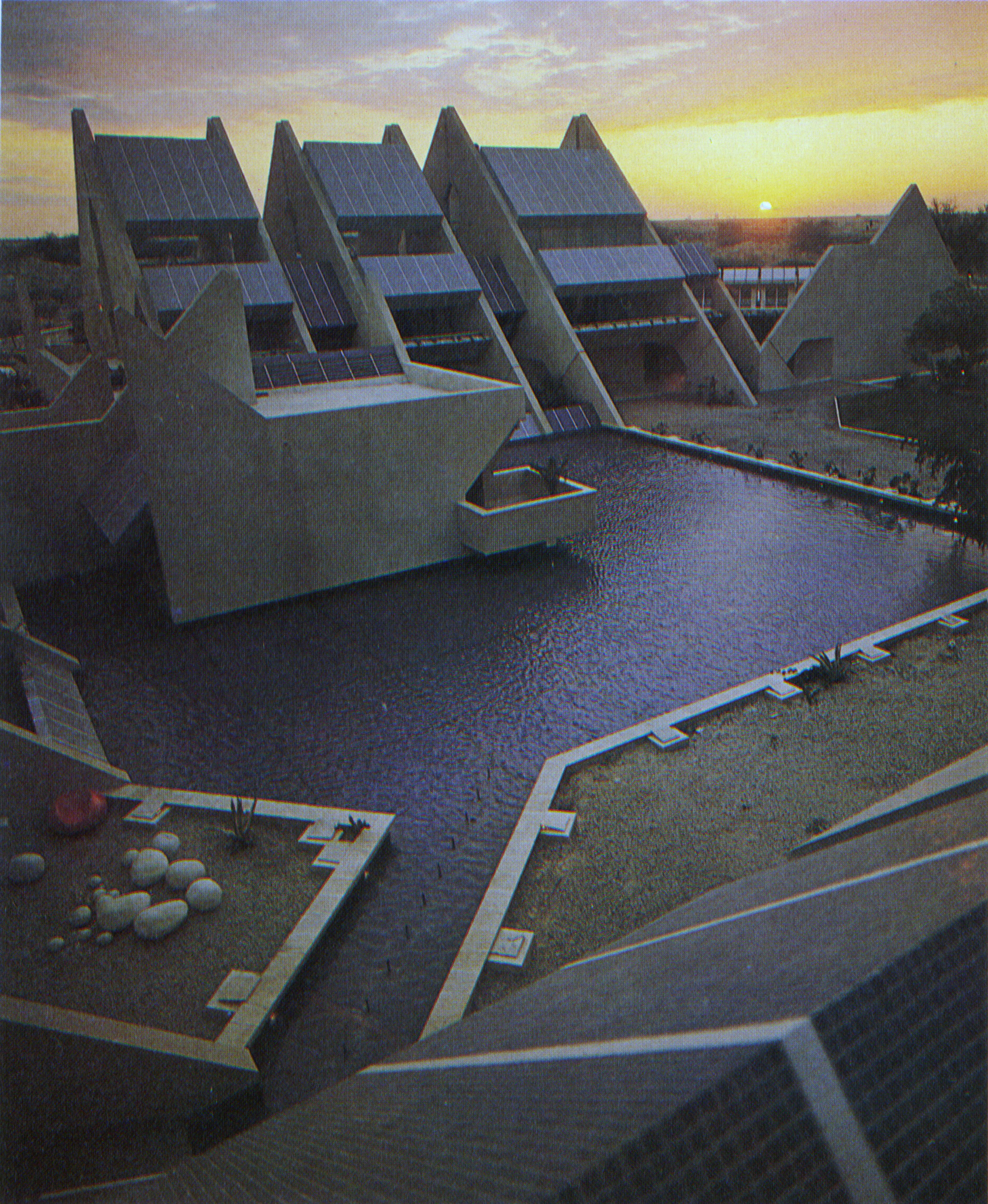

Once the residents of Masheh were moved to New Saffein, the old village was demolished and replaced by a very peculiar display of architecture. Among the new constructions were hotels, villas and apartments, royal palaces and mansions, parks, restaurants, beach clubs, a casino, shopping malls, sport clubs, and facilities such as banks, a radio and TV station, and a clinic. The planning was developed by the San Francisco-based landscape and urban planning firm Eckbo Dean Austin & Williams, working with the architecture firm Mercury Consultants from Tehran. The latter were responsible for the actual design and development of 95 percent of the buildings.

As was explained by Mahmoud Monsef of Mercury Consultants, who also became the head of the KDO, the architecture of the resort has a style that combines signs of ancient Iranian architecture with modern Western building techniques. The main element that reappears throughout the resort is a “discontinued arch,” or an arch split in the middle. Apparently, the formalism of this architecture can be traced back to the cuneiform script of ancient Iran.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Bent surfaces, slanting rectangles, and sharp points are all features of the modern buildings constructed on Kish in the late 1970s. They were to embody the island’s steep flight into the contemporary. But the island never really took off. Instead, with the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the top echelons of Kish’s establishment fled the island, and those who couldn’t were arrested. After the Revolution, the KDO practically became non-existent as 95 percent of its employees were redeemed and sent away. All the buildings in the resort area, the palaces, the hotels, the villas, and the casino were left unattended, and in no time, much of what was inside was looted or auctioned off. What remained of the buildings rapidly became dilapidated in the island’s harsh climate.

Kish became a predicament for the new government after 1979. On the one hand it represented “Western decadence” and the corrupted self-indulgence of the monarchy – all of which the new regime despised. But there were also unpaid wages and 350 million US dollars worth of national and international debts plus a huge infrastructure issue that needed to be dealt with. The post-Revolutionary government simply did not have the means to absorb this inherited excess. Various ideas were proposed: turning the island into a museum, an exile for drug addicts, a maritime university with a naval base, an international medical center, or simply returning it to the island’s indigenous people. Finally, in desperation, the government declared Kish the Islamic Republic’s first free zone in February 1980. This would, theoretically at least pave the way for the island to generate an income if it engaged in custom-free trade. However, the start of the Iran‒Iraq war that same year prevented actual realization of this plan. The prevailing weak economy of the country as a whole made it difficult for the KDO management to pay even the monthly salaries.

There was simply no traffic to and from the island, and Kish was all but isolated from the rest of the country.

It was only towards the end of the 1980s that people from mainland Iran actually began travelling to Kish. This was encouraged mainly by the passing of a bill in 1986, which not only allowed tax- and license-free import of goods (except, of course, those from America and other “denounced” countries). It also allowed tourists to buy and carry a high number of purchases (54 items per person) to the mainland, without having to pay any customs duty on the items. Things that were scarce on the mainland were suddenly available on Kish, mostly imported from across the Persian Gulf. From electronics to toys and industrial spare parts – all of them could be purchased on Kish. Even the materials needed for restoring Iran’s war-affected cities were imported through Kish.

With the Iran‒Iraq war finally over in 1989, the flow of tourists rapidly started to increase. That year the KDO was renamed the Kish Free Zone Organization. If you wanted to shop on Kish, you had to buy a so-called traveler’s card. With these cards, every single tourist was given a tax-free shopping and exporting permit. Selling these cards was one of the main sources of income for the new organization—merchants being the chief buyers. The buying and re-selling of these cards on Kish became a nasty business. Some merchants organized free tours to Kish from mainland cities and even paid an extra fee to the travelers in exchange for their cards. This is how they exported to markets in Tehran and other big cities. There were also ferryboats arriving with large groups of families from the southern provinces.

To support this “new” economy, the Kish Free Zone Organization began to build additional facilities, such as shopping centers, motels, parks, etc. To counter the growing international embargo against Iran, the island was to function as a backdoor through which alternative economic and political operations could be exercised. In a seminar about the future of Kish organized in October 1995, the head of Iran’s Council of Free Zones considered the island’s recent role as a mere importer of commodities as too limited: “What justified this role was that it encouraged national tourists to buy their goods on Kish rather than in a foreign country like Dubai.” But the future role of Kish in his view should be to provide foreign exchange earnings by attracting foreign tourists and through “re-exportation.”To this day, Iran has itself been one of the importers of re-exported goods. More than anything, re-exportation is a method to bypass trade embargos, because re-exported items do not undergo any value-added processes, so cannot be counted towards a nation’s exports. Since the mid-1990s, Dubai has been Iran’s most important re-export hub. It also serves as a pathway for smugglers to circumvent US sanctions. In that seminar, Kish was also seen as an economic model that has realized a shift from a controlled economy to an “open economy”:

Much of what is done in the free zones cannot be done on the mainland, thus we experience these activities on a smaller scale in these zones and if the results were desirable, we would do the same in the rest of the country.The head of Iran’s Council of Free Zones, see Free Zones magazine, issue no 41.

From the beginning of the 1990s onward, the emphasis was put on creating fewer social restrictions on Kish compared to the mainland. Yet this was not sufficient to encourage a flow of international tourists. Kish still had many social restrictions compared to popular holiday resorts. Even when it eased the regulations and offered extendable visas to foreigners upon their arrival, Kish became a transit destination, a place where visitors renewed their visas to travel to neighboring countries. Many tourists now hopped over from Dubai to Kish only to return the next day for their new visa. Kish however, was luring more and more tourists from cities on the mainland. The island offered a glimpse of life from “overseas” – allowable so long as it did not spill over onto the mainland. The number of annual travelers to Kish increased rapidly between 1991 and 1996 (from 254,114 to 659,140). Flights arrived more regularly from mainland cities, and Kish Air was even established. Soon various residential complexes, apartment blocks, hotels, villas and bungalows, shopping malls and commercial centers were built. In 1997, the population amounted to 12,647. Kish, previously a gateway for the import of household goods, had now become a place of leisure.

The source of income was no longer traveler’s cards but land. Land was rented out or sold for private buildings and various commercial developments and businesses. All investments were exempt from taxes in the first fifteen years, sometimes extendable to thirty years. From then on, the island went through an implosion of “self-made” architectural bricolage, mostly defined by a mixture of incongruous shapes and symbols inspired by contemporary commercial architecture catalogues, with detailing from Old Persian architecture. Nothing followed any logic of urban planning. Deer and camels were allowed to roam free across the island to promote a sense of naturalness. The ruins of an ancient city dating back to the eleventh century were excavated and renovated into tourist traps with restaurants and shops. To entertain the public, various festivals were organized. Loudspeakers installed in parks, malls, and along the roads played music all day. Even one of the beaches was assigned to foreign tourists so that men and women could swim together. For the first time since the Revolution, live music was played in cafés and restaurants. Concerts by male rock and pop bands were held. Kish advertised itself as a sun-splashed paradise. In reality, it was a national exception with a pseudo-international aura.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

These were exceptional (but short-lived) developments mostly encouraged and pushed by the head of the Kish Free Zone Organization. His plans enjoyed the support of the moderate side of the government throughout most of the 1990s. The frequent travels of the then-current president to the island were a guarantee that things were not yet surpassing their limits. Nevertheless, unfavorable voices of concern were being raised from other political camps inside the establishment, criticizing the Kish Organization for following trends contrary to the mainland ideology and cultivating non-Islamic lifestyles. It was said that Kish had “cultural issues.” The elections of 1997 resulted in a moderate reformist government, and the cultural and political scene in the country became more open. The Kish Free Zone Organization saw a role for itself in this, and started its own newspaper titled Azad, meaning “free.” This brought the organization closer to politics but also under closer public scrutiny. Ultimately, in 2000, the newspaper was banned following an article on a series of political murders in the late 1990s in addition to a cartoon that was deemed “offensive.” This was followed by the replacement of the head of the Kish Free Zone Organization that same year.

Today Kish’s main concern is still to attract foreign investors, to have Iranian entrepreneurs invest in Kish rather than in foreign countries, and to make Kish a gateway for export rather than import. However, the truth is that the policies on foreign trade and tourism remain quite undecided and even contradictory.

All of this makes the economy of Kish too unreliable and insecure for investors. In an interview two years after his replacement, the former head of the Kish Free Zone Organization replied to the question of what needed to be done in order for Kish to achieve its ideal state:

[...] The main problem in attracting tourists is the governing system’s disbelief in the tourist industry. Our main industry is oil and all attention is in that direction. We don’t look at tourism even as an alternative for increasing our GDP or tackling unemployment. Maybe as long as there is oil this situation will remain.Interview in the Haml va Naghl magazine, spring issue (2002).

Five years later, in another interview, he announced that “under no circumstances have we been successful in attracting foreign investors; we haven’t even performed effectively with regard to domestic investors.”Interview with Baran Mehri, in Sarmaye newspaper, no. 460 (2007).

Return to the Greek Ship

From the mid-1980s, the Greek ship began to lure travelers from mainland Iran. Images of it often appeared in mainland newspapers and magazines. Unofficially, the vessel had become Kish’s trademark. Naturally, the Kish Free Zone Organization wanted to know everything about the ship’s history.

They sent a fax to the Greek embassy in Tehran and the Lloyd’s Register, the British maritime classification society that keeps track of all merchant shipping. The embassy was unable to find any documents to indicate that the ship had sailed under the Greek flag. The information services of the Lloyd’s Register in London sent snippets of information: the ship’s name was Koula F and had been built in 1943 by William Hamilton & Co. in the Port of Glasgow, Scotland. It became stranded just off the island of Kish on July 25, 1966. Several unsuccessful attempts had been made by the Dutch tugboat Orinoco on July 29 and 30, 1966, to salvage the ship. The ship, however, moved only ten degrees. Meanwhile, two holes were detected in its tanks by the Orinoco salvage team. On August 7 of that year, the entire crew, with the exception of the chief officer, abandoned the Khoula F. After a survey on August 27, the salvage inspector from the Orinoco concluded that retrieving the ship was economically unfeasible. The wrecked vessel was then abandoned as a constructive total loss.

At the time of her loss, the Koula F was listed under the ownership of Paul J. Frangoulis and A. & I. Cliafas of Greece. However, before that, from 1959 to 1966, she had sailed under Iranian flag. In my own search in the Kish Library Archives, I came across a photocopied sheet of paper with an account by the inhabitants of Kish, who recalled that the ship’s crew had set the vessel alight before abandoning it. This may indeed be true, as nothing flammable has ever been found aboard the ship.

On the coastline opposite the ship, a large rudder wheel has been installed bearing a carved plate telling the story of the ship. It is a strange sight – as if the steering wheel had been moved from the ship to the shore to allow the island to sail towards where the ship had failed to return: the West, or some unattainable projection of it. The melancholy of the scenery at sunset, the dim-lit hours during which people gather to view the ship, highlights Kish’s pathological fixation and identification with the Greek ship, or rather, with her loss and wrecked state.

In the past decades, Kish has turned into an almost masochistic battlefield over this “lost destination,” that “Where/West” it wants both realized and destroyed.

This schizophrenic divide within the island has torn Kish into bits and pieces of ambivalent architecture, an architecture that is symptomatic of the island’s melancholia. If for Kish there ever was a dialogue with history, it is from this inner divide. And the ruins it cultivates give the island its geography.

In 2003, an Iranian expatriate and investor organized an architecture competition to design a huge tourist and business resort on the island, called the “Flower of the East,” destined for the northeast of the island, right where that curved tip is located. It would be 237 hectares, with a seven-star hotel and six other luxury hotels, around 4,700 luxury apartments and villas, an eighteen-hole golf course, a marina, approximately 53,000 square meters of retail space, and 80,000 square meters of office space. The heart of the resort would be transacted by a promenade lined with buildings, in which “the merits of international architecture are combined with the charm of the Middle Eastern dedication to detail” the project’s brochures claimed.

As many as twelve German architecture firms became involved in designing the resort. At the initial briefing, each was given images of famous European tourist resorts like those on the Cote d’Azur or in Nice, with focus on their nineteenth- and early twentieth-century architecture, but also the mosques and bazaars from Esfahan and Marrakech. The resort had to breathe an old European atmosphere – as if it had always been there – but combined with oriental and Middle Eastern characteristics and the high-tech contemporary architecture for which Germany is well known. The people coming from neighboring countries to the resort should imagine themselves in Mediterranean Europe (but without having traveled that far). And for those coming from farther away, Europe for instance, they should believe themselves to be in some Middle Eastern country, very likely with a European past.

It might be confusing to understand how such a resort with its emphasis on internationalism could exist in a place that has held such sour memories of international relations. There is an ambiguous zone between “resort” and “free zone” through which the “Flower of the East” articulates itself on the island (and beyond). Apparently the idea was to make the resort into a gated area with only one entrance, either to keep out unwanted guests or to keep in undesired practices. (Was this the only way the authorities could tolerate the resort?) In any case, it is exactly due to geopolitical indecisiveness that a phantasmagorical mixture of architecture as desired for the “Flower of the East” resort is imaginable. In a conversation with one of the architects involved in the competition, the issue of the possibility of such an architectural style came up. The office for which he was working did not usually design “Beaux-arts” or “oriental”-style architecture. For them, this was an exceptional situation, too. But I was curious about how they managed to become involved in the competition:

We don’t think it is interesting to transplant Western classical architecture to another location. The result would be a tacky world that is not real and would be strange anyway. So we tried to develop an architectural design that deals with the elements of classical architecture through classical utopian paintings of architecture. These pictures of non-existing urban surrounding were the sources of our design. Rather than transferring an existing architecture to another location, we reinvented a kind of utopian classical architecture as a scene and connected it to different scenes. The resulting architecture then can be from here but can also be, in an irritating way, from somewhere else – and maybe this is the expression of what a resort is really like: separated from everyday life but still existing. There is some kind of irritation attached to this situation. I think it’s very important to make this situation clear to people – they are inside and outside at the same time. They are inside this project, inside this resort doing what they want to do. But at the same time they are outside. Outside their normal life, outside the normal political conditions in Iran. And I think that only an architecture that is somehow irritating can manage that.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In 2008, the Iranian government broke its contract with the investor of the Flower of the East project and retrieved the land assigned to it. It had failed to interest enough investors to raise the 1.9 billion euros needed for the project. When the project started in 2003, the political climate in Iran was very different from that of a few years on. In early 2007, I went to Kish and visited the construction site of the resort. Nothing had been erected; not a single brick toward all those grandiose hotels and villas. Soil had been moved from one place to the next, and the otherwise flat land had become a landscape of mounds and ditches, resembling a scale-model of a sandy desert. It felt as if everything had become extinct before it was even built. I didn’t mistake this scene as some sort of regression to the origins of the island’s natural characteristics – a sandy desert. What I witnessed was a productive process, of the decomposition of something that had never materialized. Kish’s modern history became a possibility only insofar as it was a misplaced history – the misplacement to which it has always remained faithful.

This text is an edited excerpt from Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, “Kish, an Island Indecisive by Design,” in Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi (eds), Kish, an Island Indecisive by Design. Rotterdam: Nai publishers, 2012.

Video by Nasrin Tabatabai & Babak Afrassiabi, Greek ship at sunset, Kish Island, 2005, 49 min.