Wiki Commons

Exploratory drilling activities in the Chukchi Sea offshore Alaska

The Arctic Upside Down

To put current polar geoengineering scenarios and their uncertain consequences into context, literary scholar Karen Pinkus reminds us of the adventure novel Topsy-Turvy by the prolific nineteenth-century novelist Jules Verne. As she tells the hyperbolic story of the sinister plan to tilt the Earth and extract the coal below a molten Arctic, it spurs us to consider how the figure of the Vernian engineer seems to be resurrected today in an attempt to do the opposite: to reglaciate the poles.

With certain preconditions having been met, “the Arctic region is to be sold at public auction for the benefit of the highest and last bidder."Jules Verne, The Purchase of the North Pole, or Topsy-Turvy (New York: J. G. Ogilvie, 1891), 8. First published in French in 1890 as Sans dessus dessous. The English translation published one year later was translated anonymously. So reads a pronouncement of the North Polar Practical Association (N.P.P.A.), of 93 High Street, Baltimore. The remote territory for sale has only recently been confirmed to exist and has “never been touched before by mankind or discoverers” and is “absolutely uninhabited.” It is described as a large swathe of land that “belonged to no one and therefore belonged to everyone."Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 9. The phrase evokes a peculiar relationship to this space-time, echoed in what Jen Hill writes of the North Pole in the nineteenth century. The Arctic was perceived “as an imperial space that is not part of empire (because there are no economic and colonial goals in its exploration), and as a place that is everywhere … because it is nowhere.” See Jen Hill, White Horizon: The Arctic in the Nineteenth-Century British Imagination (Albany: SUNY Press, 2008), 16. In short, it is “a mystery,"Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 6. brought to us courtesy of Jules Verne in his short novel The Purchase of the North Pole, or Topsy-Turvy (originally published as Sans dessus dessous in 1889).Reaching the North Pole is a relatively common goal of explorers in Verne’s fiction. See Michel Butor’s 1949 essay, “La point suprême et l’âge d’or à travers quelques oeuvres de Jules Verne,” in Répertoire, vol. 1 (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1960). To be clear, this was not the first time Verne raised for his readers the idea of this terra nullius at the top of the Earth. They traveled up as far as the 84th parallel with Captain Hatteras in Verne’s second major novel, The Englishman at the North Pole, for instance. Moreover, the members of the Baltimore Gun Club, who spur the action in Topsy-Turvy, are recurring characters from Verne’s oeuvre, best known for another massive technological undertaking that involved traveling to our nearest celestial body in From the Earth to the Moon. Still, this particular tale of Arctic enterprise stands on its own and requires no prior familiarity.

The “boys of all ages” who consumed Verne’s adventures, first serialized and then bound in book form, would likely have been drawn into the story by the opening pages of Topsy-Turvy, telling of strange financial transactions. Like the global nineteenth-century public Verne describes in the novel, his readers would definitely have been curious to know: What would possess a group of Americans to exorbitantly outbid all others for the rights to the North Pole?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

As detailed in Topsy-Turvy, the fine print of the auction circular stipulates that “the right of proprietorship should not depend upon any chances or changes in the country, no matter whether these changes were in the position or climate of the country."Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 8. That phrasing might strike some potential bidders as odd. Is it simply a disclaimer meant to indemnify the seller from any responsibility, even an act of God? Perhaps, as a Philadelphia newspaper had it,

the future purchasers of the Artic region have information that a hard stone comet will strike this world under such conditions that its blow will produce geographic and meteorological changes such as the purchasers of the region will profit by.Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 8.

Yes, say the men of science in Verne’s narrative, in the deep past the poles may almost certainly have been fertile. And they might become so again, as the Earth shifts on its axis. But that past and that future are not compatible with the human time of our entrepreneurial Baltimoreans preparing for a large purchase. There must be coal in the North Pole. Why?

Because very probably at the geological formation of the world, the sun was such that the difference of temperature around the equator and the poles were not appreciable. Then immense forests covered this unknown polar region a long time before mankind appeared, and when our planet was submitted to the incessant action of heat and humidity. This theory the journals, magazines, and reviews publish in a thousand different articles either in a joking or serious way. And these large forests, which disappeared with the gigantic changes of the earth before it had taken its present form must certainly have changed and transformed under the lapses of time and the action of internal heat and water into coal mines.” These, Verne supposes, are “undeniable facts.Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 29.

Once the auction is finished, the mystery is no longer why the Americans made the purchase—they admit they intend to mine for coal—but how they intend to get up there and open up mines and lines of transport. After a long guessing game that takes up many pages of the text, the president of the Baltimore Gun Club, Impey Barbicane, admits that he and his allies are planning an operation, an enormous explosion to

bring the pole at or about the sixty-sevenths parallel of latitude, then the earth will be similar to the planet Jupiter, whose axis is nearly perpendicular to the plane of its orbit. Now this movement of 23 degrees 28 minutes will be sufficient to give at our North Pole such a degree of heat that it will melt in less than no time the icebergs and field which have been there for thousands of years. … It is the sun which will take upon himself the melting of the icebergs and fields around the North Pole, and thus make access to the same very easy.Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 42.

And if the reader is not certain how to react, Verne explains that the result of this pronouncement among the assembled men of science and industry is utter amazement.

And yes, for better or worse, the Americans admit there will likely be some serious collateral consequences of this project. As Verne explains,

The most curious thing of all would be the absence of the different seasons of the year. Now there were Summer, Winter, Fall, and Spring. The people living on Jupiter did not know these seasons at all. After this experiment people living on this globe would not know them either. As soon as the new axis would be in smooth working order there would be no more ice regions, nor torrid zones, but the whole world would have an even temperature climate.Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 43.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Indeed, in order to achieve this massive terra-reformation, the Americans have engaged a genius mathematician, Mr. Maston. His calculations have helped them draw up plans to dig down far below the surface a massive borehole for a massive rocket that will then be thrust upward to change the climate of the planet. This will facilitate the extraction of coal from deep down to serve various useful functions on the surface. Naturally, the controversial project is top secret. Even after Maston is jailed, he refuses to give up the location of where his rocket launcher is being constructed. This leaves the public to speculate about possible locations:

Was it on a deserted island in the Pacific Ocean or in the Indian Ocean? But there were no more deserted islands: the English had gobbled them all up. Perhaps, one remarked, they might be in some part of the arctic regions. No, this could not be, as it was simply because they could not be reached that the N.P.P.A. was going to remove them.Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 58.

The North Pole, in this novel at least, is the last frontier, or nearly so.

As time goes on, some scientists point out that beyond a leveling democratization of the climate, other devastating collateral effects may well occur as a result of the explosion—suffocation in some parts of the globe, drowning in others, and so on. These effects might not be even or linear or predictable, and so there is an urgent need to stop the Baltimoreans from completing their plot. Finally, through an informant, officials learn of the secret site of the borehole that will serve as a cannon for the rocket. Deep in Zanzibar, thousands are working diligently under the iron rule of Sultan Bali-Bali. A good choice for a secret project! And as a side benefit, there is plenty of iron and coal on the surface, Verne interjects—no need to dig, “only stoop down to pick it up."Verne, Topsy-Turvy, 72. But the officials are too late to stop the imminent explosion. The hour of reckoning is nigh!

Nevertheless, and to the great relief of the great majority of Earth dwellers, the explosion, having been grossly miscalculated thanks to an ill-timed telephone call by the wealthy widow who provided financial backing for the whole enterprise, fails to produce more than local damage. The planet is spared. Maston is disgraced, shamed, perhaps even into proposing to the widow. Life goes on as before on the surface of the planet.

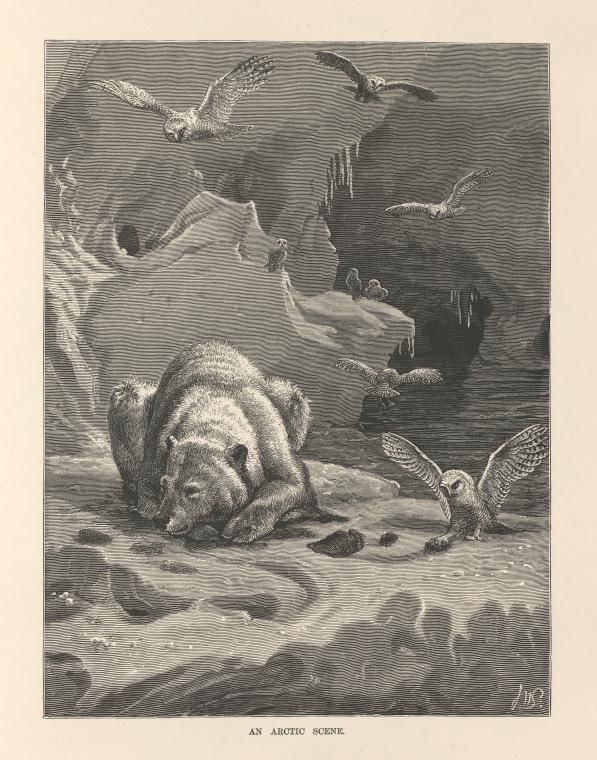

Ultimately, then, Topsy-Turvy is a novel about the Arctic with no Arctic. We never get there: no awkward encounters with Indigenous knowledge. No flag planting or nationalist triumphs. No icy expanses, death, cannibalism, or drama, as in John Franklin’s lost expedition to the Northwest Passage that so captured the imagination of the nineteenth century. No ships brimming with supplies and relics from home, and, certainly, no great (albeit finite) new fonts of coal.Adriana Craciun offers a rich history of the textual and material culture of Arctic exploration in Writing Arctic Disaster: Authorship and Exploration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016). While the novel is parodic to a degree, Verne still manages to dangle the Arctic as a sliver of hope for his readers—something to strive for, a bit of uncolonized space, like the moon (and the rest of the universe). In a sense, he acknowledges that we are running out of frontiers, so we have to invent new ones. As the hero scientist Prof. Otto Lidenbrock tells his nephew in Journey to the Center of the Earth, what lies below our feet is much more interesting that what happens in daily life, on the surface: “pas dessus, mais dessous.” Topsy-turvy, in other words.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Certainly, Jules Verne could not have been expected to know that in less than two centuries, the problem facing mankind would not be a scarcity of coal or the technology to extract it (let alone oil) from recalcitrant or remote sites, but rather an excess of coal combusted between his life and ours would have altered the climate. Indeed, we find in this short nineteenth-century novel an infinitesimally improbable scenario of unfathomably fast climatic change brought about by a violently disruptive geoengineering project to speed up the process of slow change over deep time. The same rational and sober engineers—Verne’s favorite characters—are instead now considering several megaprojects and mitigation scenarios to achieve the opposite of the Baltimore Gun Club: to re-glaciate the poles in order to slow down sea-level rise.See, for instance, John C. Moore, Rupert Gladstone, Thomas Zwinger, and Michael Wolovick, “Geoengineer Polar Glaciers to Slow Sea-Level Rise,” Nature, March 14, 2018, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-03036-4; and Jason Thomson, “Can We Slow Sea Level Rise by Pumping Water onto Antarctica?,” Christian Science Monitor, March 10, 2016, https://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2016/0310/Can-we-slow-sea-level-rise-by-pumping-water-onto-Antarctica. Such scenarios are typically accompanied by caveats, including cost, potential carbon intensity, and the “moral hazard” of addressing a symptom of climate change without addressing the cause(s), that is, without reducing greenhouse-gas levels in the atmosphere. If undertaken, would polar geoengineering produce unintended consequences? And how should such projects be governed? Could the fear of irreversible Arctic melting bring together various nation-states to cooperate?A recent special issue of Nature on Antarctica (June 14, 2018) takes a somber but hopeful tone toward disruptive arctic melting. Or will cooperation materialize instead of overexploitation of the resources yielded up in the new channels of access? Or could the “Arctic project” consist of a series of smaller but cumulative actions, displaced to parts of the inhabited world and not intervening on the ice itself but rather stabilizing emissions, to stem catastrophic flooding of cities elsewhere? And is there any time left before we reach an absolute tipping, or melting, point?

It might be comforting, I suppose, to be able to have faith in the figure of the Vernian engineer to solve the crisis and provide answers to the questions above. It might be comforting to be able to imagine the Arctic as far off, uncharted, filled with potential bounty, absolutely stable, and always slightly out of reach. Wouldn't it be nice?