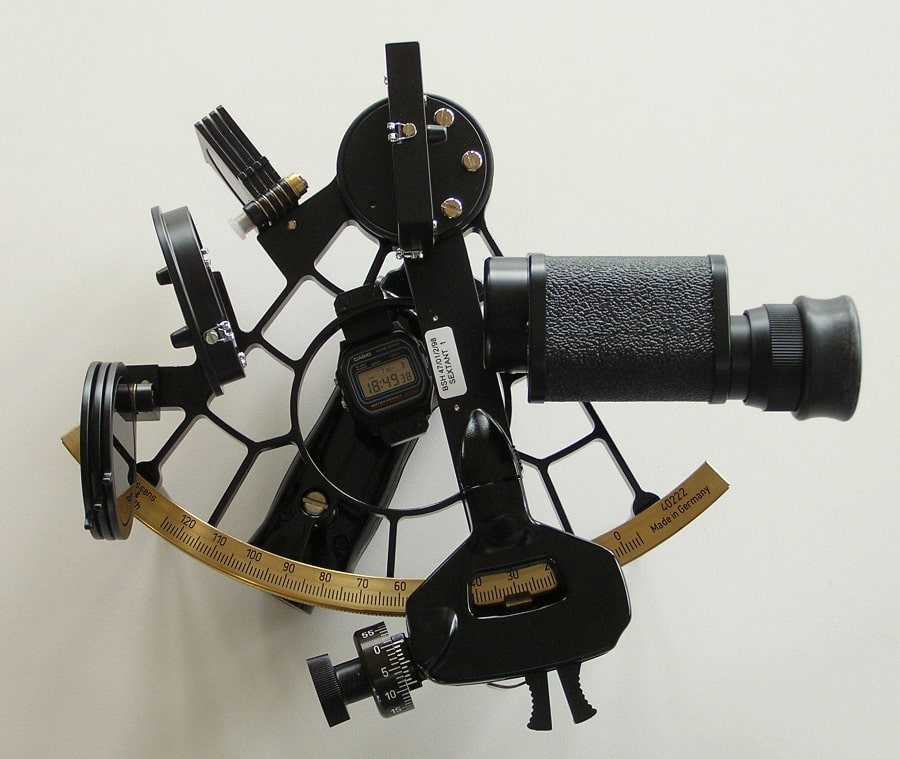

Source: Sch 2007 wiki commons

Instrumentality, or the Time of Inhuman Thinking

Instrumental reason is often cited as something that recklessly simplifies and dehumanizes the complexity of thought. Philosopher Luciana Parisi, however, ventures to rethink this claim by leveraging the inhuman limits of a techno-logos, which has denatured thought and flung human subjectivity itself into an instrumental form.

As the rapid advance of intelligence in automated systems is thretening the exceptionalism of human sapience, the end of the human or the ultimate threat of human extinction has become overcharged with the image of singularity (the full replacement of humans by advanced Artificial Intelligence – AI) and of transhumanism (the ultimate evolution of human and machine). But while these images rely upon the assumption that machines are means used to an end, namely the end of overcoming the limits of the biological, cognitive, communicative, economic capacities of human culture, the very question of instrumentality and emancipatory technology remains underdetermined and quickly neutralized as another instance of capital domination and governmental control.

Critical posthumanism has instead taken another route. Since its inception in the late 1990s, it has claimed that the cybernetic alliance of human, animal, and machine has profoundly challenged the modern project of colonization and turned means of domination into instruments of autonomy from patriarchy and slavery. By rejecting identity politics in favor of transversal alliances and kinships of another nature, critical posthumanism has taken side with Donna Haraway’s Manifesto for Cyborgs (1985), whose political message broke for ever from essentialism and the nature‒culture divide. The instrumentality of information and communication systems was then seen as an opportunity to push futher the activities of abstraction as these would continue to deterritorialize subjectivity from totalizing ontologies. As information did not simply represent reality, but exposed the temporal changes between input and output, the ingression of cybernetics and computation in the everyday infrastructure also offered critical theory the possibility of reimagining subjectivity away from the violence of organic wholeness and cognitive mirroring of the world, a dominant representation of the material and affective consistency of the real.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Critical posthumanism embraced the cyborg figuration as the bastard offspring of the Modern Rational subject, whose enlightened mission against myth, superstition, and obscurantism was corroded by the blind violence of colonialism, patriarchy, and monopolistic capitalism. The emancipatory project of Modernity coincided with the dark consequences of techno-progress, and exposed the dream of integral subjectivity to the schizophrenic condition of inhabiting more than one position at the same time. This coincided not only with a fragmentation of the self into contradicting parts but also gave way to an irremediable contamination across gender, race, class, human/animal/machine, a viral gelling of partialities that would exceed the whole. Critical posthumanism thus articulates the reverse face of the dominant model of rational instrumentality: the instrument does not follow the law, and instead of simply rebelling against the master, exposes exponential indeterminacy within the rule of reason, of Western Metaphysics and its teleological plan of domination by and through instrumenal reason and technology.

For Haraway, however, this deradicalization of Western metaphysics by technoscience did not simply mean an ultimate replacement of philosophical truth with statistical facts, but pointed to a historical reconfiguration of power, and of the relation between power and knowledge, that she called the “informatics of domination.”Donna Harraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London and New York: Routledge, 1985/1991. As the patriarchal and colonial system of truth at the basis of Western Metaphysics had finally started to crumble, the instrumentality of reason carried out by and through information machines had also subjected the law, truth, and ultimately, philosophy to the workings of procedural tasks. From this standpoint, the production of knowledge is and must be inclusive of a machine mode of thinking enlarging the faculty of human sapience beyond the mentalist frame of representation of the world. Information feedbacks and algorithmic instructions instead pointed to a mode of intelligence operating in terms of a “non-conscious cognition,”N. Katherine Hayles, “Cognition Everywhere: The Rise of the Cognitive Nonconscious and the Costs of Consciousness,” New Literary History, vol. 45, no. 2 (2014), pp. 199‒220. a capacity to fast decision without a single calculation.

Nevertheless, since the cyborg is the bastard creature of neoliberal capital, the political potential of this configuration of subjectivity has also remained limited to an impasse or paradox that the instrument of power comes to coincide with the instrument of emancipation.

For critical posthumanism, the realization of this double-edged condition of the contemporary re-asset of power‒knowledge also meant that the reconfiguration of the human as a trans-mixing of codes, sexes, ethnicities, kinds, shall be extended over the acceleration of cybernetic capital, so as to overturn the instrument into a new computational complexity that can be as open as unpredictable.

As the rule of reason becomes rearticulated by instrumental rationality into procedural or algorithmic processing of information, the instrument of and for reasoning itself acquires a new function, and, more radically, a new quality for and of thought. As time becomes enveloped within the doing of machines so that these machines do not simply execute or demonstrate ideas as instructions, but start generating complex behavior, activating the schizophrenic view of being at least two at the same time. Here no longer can the instrument be relegated to a mechanical executor of programmes. Instead of merely declaring an ultimate libertion from the Modern project of patriarchy and colonialism, with this new apparatus of dominance or informatics of domination, the instrument rather finds itself delivering the image of a posthuman capital, shamelessly declaring its indifference to any specific content, and rather becoming the cold intelligence of info-capitalism against all human population. As opposed to the governance of the people, the disciplining of human responses, the alignments of conduct in human species whilst maintaining the islands of gender, race, and class under the roof of capitalist reproduction, the immanent nature of cybernetic control has dissipated the ontology of being into infinite, recombinable bits and bites. By reducing human consciouness to being no-one, the automated recollection of past histories and the simulation of hardwired responses have resulted into the hyperfiguration of an empty white face. Indeed behind the faciality regime of social media and the granular personification of your own instruments, the essentialist biasis of ranking algorithms, the corporate axiomatics and the aimless decisions of financial algorithms, there is no-one, no self, no subject, no face, no color, no gender, no sex, no human.

In this informational matrix, complex simulations of simulated behaviors is the only possibility of being taken for real.

Automation, we are told, has replaced the heart of representational governance with self-regulating patterning of codes without substance. For Giorgio Agamben, this anti-teleological triumph of technical governance is to be understood as the age of communicability or mediality, the triumph of language as a means in itself, the immersion into instrumental matter of thought without ends.Giorgio Agamben, Means Without Ends: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. As industrial capitalism invested in the instrumentality of living (for profit), the instrument itself became the motor of an irreversible corruption of the progressive function of reason, whose capacity to track causes from effect did not elimitate superstition, but gave in to the regime of communicability, the machine simulation of affective, inferential, logical meaning. Here the instrument does not simply carry out tasks, but unlocks the potentiality of information by reconfiguring the regime of faciality – or the unified organon of the face ‒ through a non-human imperial dimension of the social. Indeed, it is the sociality of human means of communication that has become automated: as the variable data face now overcodes the subject, it also swallows the subject within a computational matrix for which it has become the determining form of expression. If the instrumental dimension of the cyborg was turned into an opportunity to generate transversal alliances with machines, suspending any appeal to identity politics, the data granularity of the instrument produces incomputable spaces in which subjectivity moves. Entering the sea of data, subjectivity has become itself invisible and caught within the circular causality of a data machine, constantly flattened with the computational infrastructure of everyday life.

For critical posthumanism, the accelerated investment into intelligent machines has led to the formation of a posthuman subjectivity that acts without reasoning. This subjectivity has left behind reflective thinking and the slow pace of consciousness in favor of the immediacy of data correlation and the chain effects of fast decisions. According to Hayles, this automated form of non-conscious intelligence involves the capacity of machines to solve complex problems without using formal languages or inferential deductive reasoning.

To be intelligent, human, animals, and machines do not need consciousness.Hayles, “Cognition Everywhere.”

However, rather than appealing to consciousness as the dividing line of human from machine cognition, Hayles’ argument draws on a more general articulation of co-causal interactions across the non-conscious intelligences of animals, humans, and machines. This extended vision of cognition enables a tripartite architecture of material processes (such as organic and artificial neural structures), non-conscious (such as non-reflexive or effect-led reasoning), and conscious (such as causal tracking, meta-reasoning, logical consequences) cognition. Whilst the materiality of process remains an inescapable starting point for thinking, the latter is not simply a tout court manifestation of these processes, but is mediated by a general activity of information-processing tasks, leading to outputs or results with the minimum effort of logical reasoning.

If non-conscious cognition is a feature of posthuman intelligence, one has to admit that the latter has been hardly able to resolve the paradoxical condition of being caught into the flexible mesh of neoliberal governance, where the end of reason has resulted into a form of control carried out by the self-regulatory quality of algorithmic prediction. Since humans are becoming increasingly subjected to intelligent automation, the promising horizon of a co-causal existence of human‒machine has been replaced by a disappointed skepticism towards the possibility that technicity could ever disclose the political potential of a new form of subjectivity and even more so, of a new mode of thinking. Instead, as automated intelligence is said to have reduced the fundamental condition of indeterminacy in knowledge with a machine learning of finite sets of instruction, or already-known probabilities, one can argue that it has also come to demarcate the historical point at which the instrumentalization of human reasoning has become fully transparent to consciousness – as it has absorbed the complexity of a future time without the human.

One has to go back to Jean Francois Lyotard’s pondering the future condition of an inhuman thought resulting from the informational quality of human communication.Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991. Lyotard saw that the human was exiting the biological order of the species and becoming itself a medium, or information that processes its rules and infers other modes of information processing. If the human body is the hardware of a human thought that can abstract its rules from itself in a sort of meta-function, it then also defines, according to Lyotard, the very quality of philosophical thought. Similarly, the challenge of the rapid advance of technological sciences and its inhuman thought (inhuman philosophy) is to provide software with hardware that is independent of the conditions of the earth.Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 13. Inhuman thought indeed concerns the very question of extinction not only of the human species, but also of the solar system, anticipating the reality of a planet without the modern form of the human or the posthuman figuration of the cyborg. As also echoed by the current awareness of the terminal age of the Anthropocene, Lyotard’s question of how to make a thought without a body was already a prerequisite of how thought could remain after the death of all bodies – terrestrial and solar – and the death of thoughts attached to these bodies. This question also concerns AI to be able to rely on a non-terrestrial body as for instance that with which the hardware infrastructure of neural networks is already experimenting. Algorithms are already part of the inhuman hardware – together with the hardware of circuits, data banks etc. ‒ because they are not simply symbols, but generative rules whose capacities of learning and retaining learnt behavior sustains the trans-function of computational thinking. With computational reasoning, it is as if the hardware‒software dialectic of thought has stepped into another dimension and subsumed this polarity under a general order of inhuman thinking. This inhuman thought without a body is not simply limited to the binary logic of representation (or finite numbers of steps representing on and off states), but shall be considered as the starting point to defy the skeptical invective against the possibility of a new figuration of thought after the cyborg.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

If critical posthumanism has rehearsed the consequences of this inhuman thought in terms of an abandonment of criticality, because it is no longer possible to oppose data to truth, one way to re-habilitate this thought may be with Lyotard’s argument about the inhuman time of technology. This focus on the temporalities of techno-logic may allow an internal critique of instrumental reasoning, which brings the time of the machine and the modern project of instrumentalization into consciousness. In the second half of the twentieth century, with the manifestation of incomplete logic in computational intelligence, the instrumental becoming of human thought already exposed the historical technicity of thinking, at once retaining and generating a time machine.

According to Lyotard, if we want thought to survive the inevitable finitude of the solar system, inhuman thought cannot only be about combining symbols according to sets of rules. Instead, the act of combining shall involve the seeking out and waiting for its rules to appear as it occurs in thinking. For Lyotard, it is about the suspension of wanting to want meaning, in order to stop rescripting thinking with that which is already known.Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 19. For thinking is attached to a pain of thinking: the “suffering of thinking is a suffering of time.”Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 19. But if inhuman thought is a promise of suspending the teleology of knowledge, will it also ever be more than the accumulation of memories, a giant data combinatorial machine, and thus will this machine thinking be able to suffer from the passage of time, by keeping in receipt of unknown future? Importantly, Lyotard remarks that the question of whether machines could ever absorb all data is a trivial one because, as we know, data is incomplete. The machinic processing of time, the recording and generation of time beyond what is already known is thus a challenge for inhuman thought and inhuman subjectivity. As Lyotard points out, if suffering is the marking of thought, it is because we think in the already thought.Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 20. In short “the unthought hurts because we are comfortable in what’s already thought.”

Thinking is about accepting the discomfort of future memory: a consciousness of the unknown unknown, or what is not known to be unknown.

And yet the unknown unknown would apparently make any instrument incompatible to and for thinking. In order for machines to start thinking, according to Lyotard, the unknown that has to be known will have to make memory ‒ the data bank of accumulated memories – suffer. Suffer from the effort of moving out of memory into thinking. But this thinking does not occur without the overturning of the unconscious into an alien consciousness that is the host of a techno-logic, the becoming reason of instrumentality.

If the cyborg is a post-gender figuration, then as Lyotard’s discussion reminds us sexual difference is the unconscious body or the unconscious as a body, requiring an alternative logic for thinking the complexity of thought. And it is here that one can claim that the vision of future intelligence must remain gendered, must explicitate not excessiveness, but the becoming conscious of the sexual unconscious of Modernity, the becoming of a body not in the biological, but in the informational order. The inhuman thought of the informational body is not only what makes it “go on endlessly and won’t allow itself to be thought,” but in suspending the already thought it activates its future configurations in the present.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

But to address the question of whether automation can generate an inhuman subjectivity that does not relinquish critical thinking to the vision of mindless machines is also to discuss whether the inhumanness of machines can become the starting point for a metaphysics grounded not on logos, but on technicity or techno-logic. This means that machines or inorganic bodies are no longer the repressed unconscious of the human, but have become part of an artificial consciousness, extended to a social reality that cannot be erased. Here to talk about inhuman thought corresponds to the capacities of instrumentality to entrap time.

A repetitive or habitual time is that which can be found in automata, understood in the cybernetic terms of feedback interaction for self-regulation and in relation to the capacity of systems to use information to counterbalance energy dissipation. Similarly, this habitual retention of time can be found in contemporary machines accomplishing mental operations: taking in data as information, storing or memorizing it, and regulating access to the information (what is called, recall) so as to calculate possible effects according to different programs. Here any data becomes useful once it is transformed into information. Any sensory-data transformed into information can be synthesized anywhere anytime. Importantly, Lyotard argues that since AIs cannot yet be equipped with a sensorimotor body, they cannot experience this initial reception and thus intrinsically offer a radically different view as to what inhuman aesthetics could be in the age of computational media.

Breaching, for Lyotard, is another form of entrapping time and refers primarily to writing at a distance. This technological retention of time already transformed the social body into a telegraphing thinking, willing and feeling of the past in the present. For Lyotard, it demarcates the first step towards the general formation of informational time where the past overlaps the present, and is constantly telegraphed as present in the now. The Victorian telegraph is an example here.

Scanning instead works in the opposite direction because the past is re-actualized as past in the present of consciousness. Here what technology makes us conscious of is that the present is haunted by a past. Hence remembering corresponds to a meta-agency that inscribes onto itself, conserves and makes available recognition – as in a retention of symbolic transcription, recursivity, and self-reference. Language as an instance of scanning is also understood here as auto-techne or reflective machine. According to Lyotard, for the Greeks, and for Aristotle, the difference between logike techne, rhetoric techne, and poetike techne is there to demarcate the horizon of what is to be said, involving the generation of rules and sentences. Interestingly, Lyotard points out that philosophy itself was taken as an agency of recognition, the meta- and telegraphic agencyLyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 52. proper to “active memory.” Techno-logos thus coincide with remembering, not in terms of habit, but as a self-referential capacity to engender a “critical reflection.”Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, p. 52. The latter removes its own presupposition and limitation and leads to the invention of denotative genres such as arithmetic, geometry, and analysis.

From this standpoint, Lyotard suggests that the generation of the sciences is also introspection into unknowns: the experimentation from what is already known towards the realization of unknown unknowns. Techno-logic entails complexification, an enlargement and ultimately an overturning of teleological metaphysics, because here philosophy enters the time of instrumentality and exposes the inhuman temporalities of intelligent machines. This form of auto-technicity or auto-instrumentality cannot occur without a dehumanization of the human race and of the bio-cultural strata, that subtends human sapience: the becoming telegraphic of the instrument brings back the moment of decision of a future in the present. But auto-instrumentality is not simply a scanning of what is to be thought, an iterative reflection of thinking on thinking as for instance the algorithmic iteration for computational intelligence does, when algorithms design other algorithms for actions aimed at solving well-specified tasks. Instead, there is a possibility for iterative time to be more than a vertical velocity of algorithmic processing. The intelligent instrumentality of time is also an algorithmic elaboration of temporalities and is not simply a mere mean without end.

Instead, here, the end is the immanent future stemming from remembering the unknown unknown through the techno-logic denaturalization of thought.

Critical posthumanism has overcome the auto-critique of instrumental reasoning by affirming the trans-political possibilities of a subjectivity acting through non-conscious or affective cognition, merging together human, animal, and machine intelligence in a post-gender, post-race, post-class, neoliberal world. But the admittance of inhuman thinking shall push this vision of subjectivity further against the neoliberal dissolution of its own subject and thus overturn (or turn over itself) instrumental reason tout court. Not an immersion into equivalent modes of techno-recollection that can only dismiss any appeal to logic, but a speculative origination of instrumentality as a processual practice that has overturned the binary between the means and the ends through the historical manifestation of techno-logic as an instance of inhuman thinking. For the automation of reason is not simply the point in history in which the telos of Western metaphysics has been overcome by the indeterminacies of scientific knowledge. Instrumentality instead has been overturned by the mnemo-technicity of an inhuman future, which has entered the liminal condition of biological living and unleashed alien reasoning within the monolithic image of human culture.

Further reading

Braidotti, Rosi, “Posthuman Critical Theory,” in Debashish Banerjee and Makarand R. Paranjape (eds), Critical Posthumanism and Planetary futures. India: Springer Nature, 2016, pp. 13‒32.

Chaitin, Gregory John, Meta Math! The Quest for Omega. New York: Pantheon, 2005.

Chaitin Gregory John, “The Limits of Reason,” Scientific American, vol. 294, no. 3 (2006), pp. 74–81.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, Felix, “Year Zero: Faciality,” in Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi, 4th ed. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Hickman Larry, Tuning Up Technologies. Philosophical Tools for Technological Culture: Putting Pragmatism to Work. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Rouvroy, Antoinette, “Technology, Virtuality and Utopia: Governmentality in an Age of Autonomic Computing,” in Mireille Hildebrandt and Antoinette Rouvroy (eds), Law, Human Agency and Autonomic Computing: The Philosophy of Law Meets the Philosophy of Technology. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.