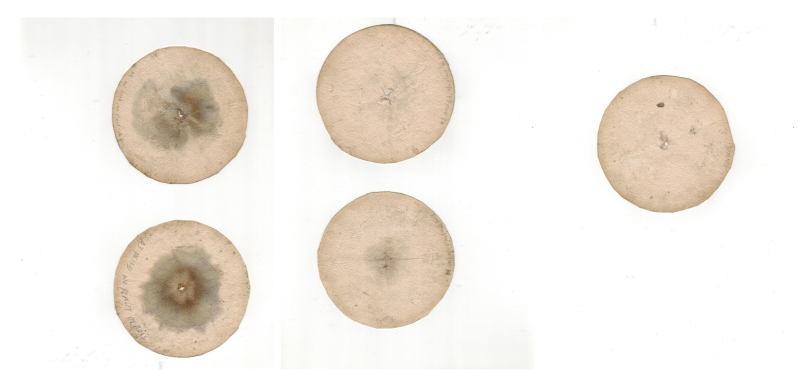

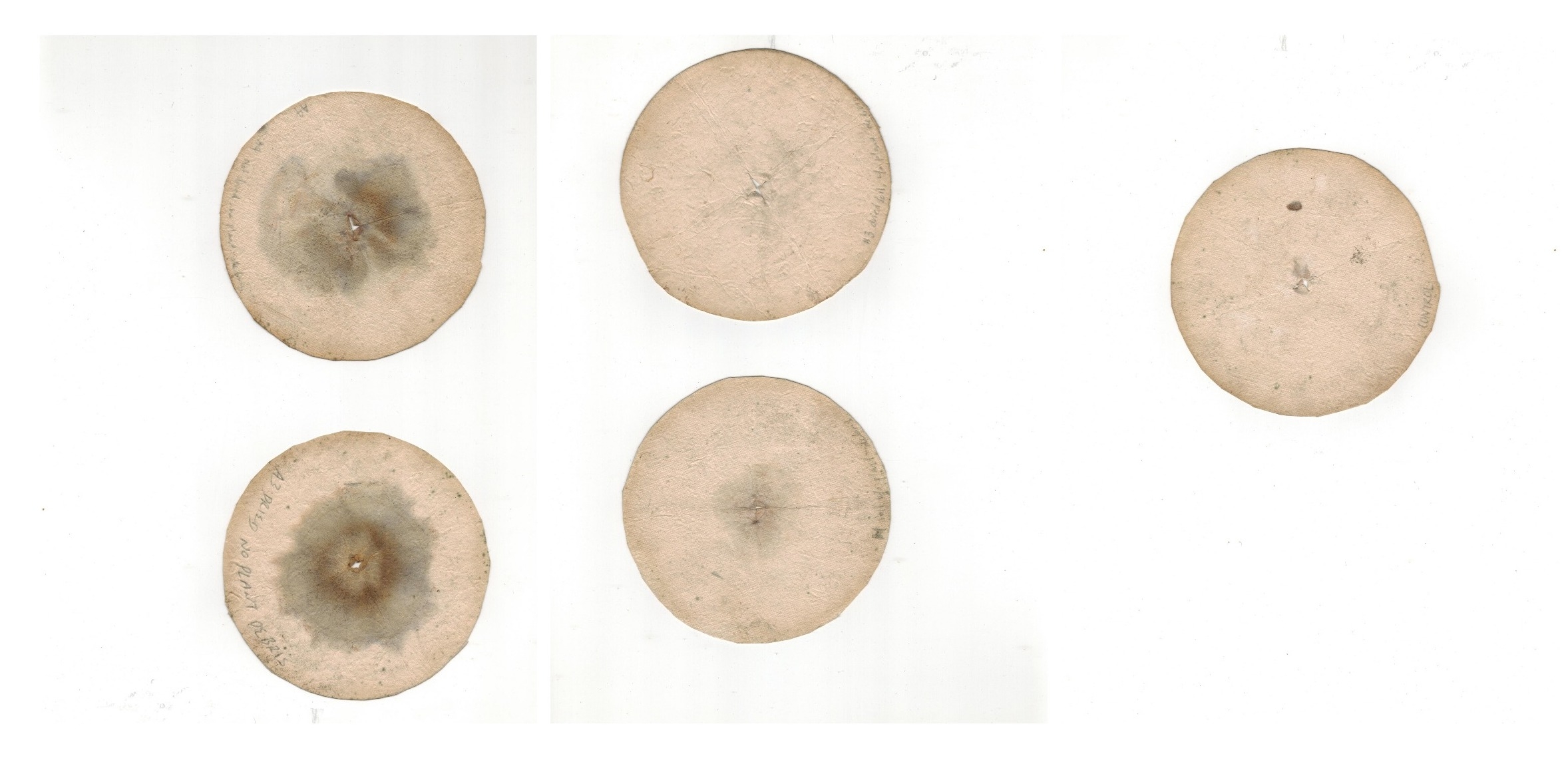

Soil Chromatograms

Soil’s Metabolic Rift: Metabolizing Hope, Interrupting the Medium

What can we learn about care and processing emotions from soil cultivation? Activist and geography scholar Huiying Ng reflects on the unintentional effects of metabolic rifts in the geological and chemical realms, as they become enmeshed within the emotional fissures underlying our current social and cultural spheres. Ng identifies such shifts in the metabolism of emotional culture as potential paths for developing alternative forms for living with others.

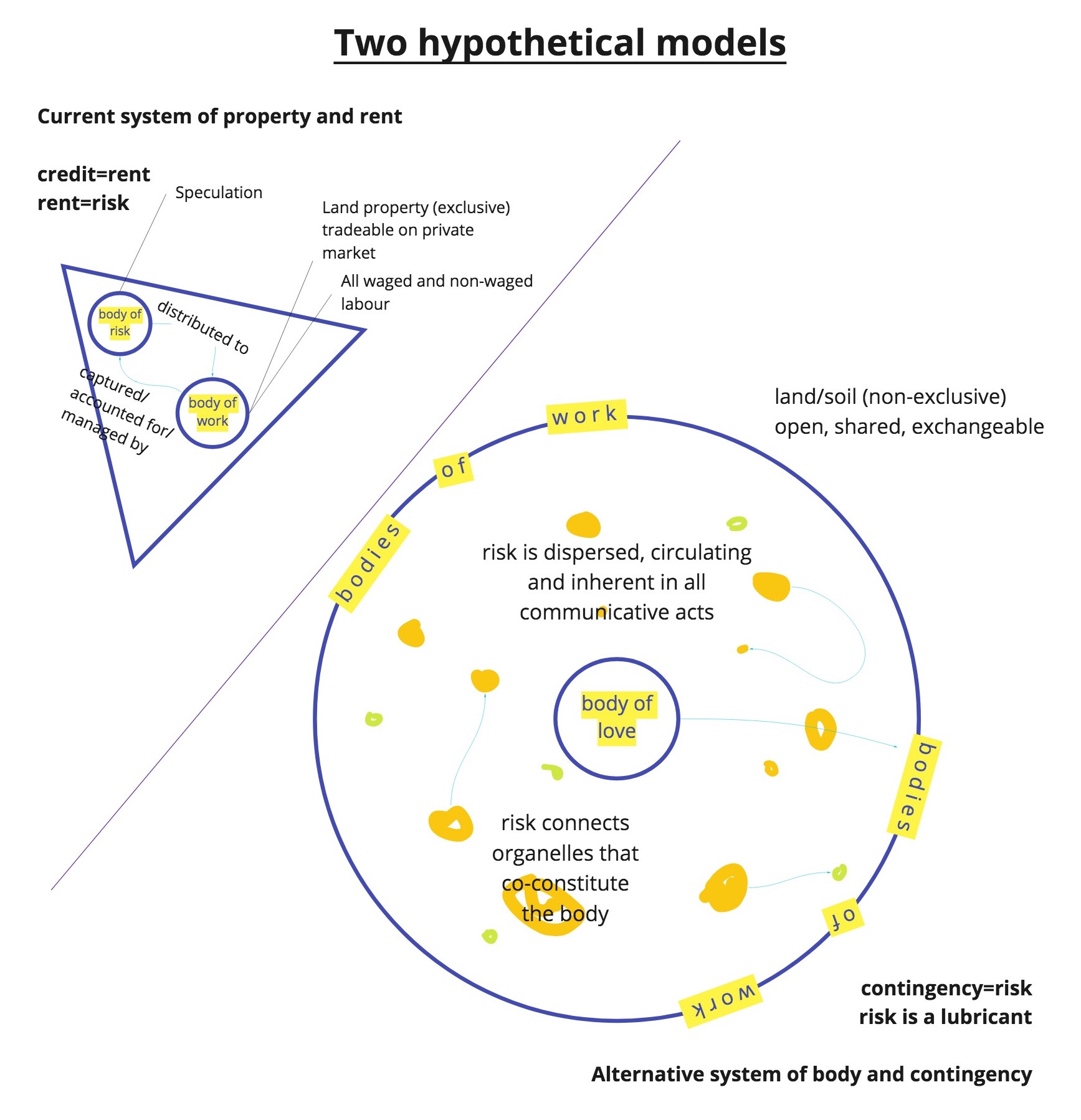

Metabolic rifts create unintended effects, both social and ecological.I use John Bellamy Foster’s (1999) concept of the metabolic rift, which is an extension of Karl Marx’s concept of metabolic crises. The metabolic rift describes a break in the relationship between nature and society. It relates to nutrient depletion in the countryside, water and street pollution in the cities, but also to the alienation of people from nature. It describes a rift in the flow of materials and energy, the form of which is shaped by social relations. As such the metabolic rift includes the effects of capital—urbanization, the expansion of global commodity chains, and processes of migration—on the mental, social, and ecological health of people and the earth. See John Bellamy Foster, “Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift : Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (2): 366–405 (1999), doi:10.1086/210315. The disruption of the nutrient cycling process, as soils are transferred, food is transported, and industrial fertilizers accumulate and leach into land and ocean ecosystems, has led to severe species loss and a narrowing genetic pool of cultivars. But metabolic rifts also involve emotional rifts, which have their own unintended effects and reactionary affects: alienation, grudges, wars, and fundamentalisms. As we begin to observe how Earth’s metabolic rhythms are made to converge with anthropocentric needs, and how we cultivate our emotional attachments around monuments to metabolic rifts (the shopping mall, cities built on reclaimed shores, mega-dams, nuclear reactors, and perhaps the most compelling rift of all: neocolonial space expeditions), we begin to perceive hints of a shared synchrony between ourselves and the planet. We—us, the multiple beings that compose the planet, and the planet itself—share the same bodily arrhythmia. Yet the recursive loops of a kidney clearing toxins from the body, of a mining operation dumping contaminants into a river upstream from a village, of a surgeon removing cancerous growth during an invasive operation, and of legislative bodies arbitrating between the health of corporations and that of individuals are all feedback functions that move at different paces. Clearly, our bodies bear the traces of multiple temporal rhythms. And, we might also say, our bodies are repositories of distributed risk.

The metabolic rifts of material society are strung tightly to emotional rifts. By attending to emotional culture, understanding the metabolism of affect and emotion, we may begin to upset the pyramid of risks and its associated affects. That is, we might start to reshape the implicit relations and value orientations that we bring to bodies—all bodies—around us and step into a relationality that observes scars and transmits healing.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

I. Emotional Culture in a Food System: A Sociotechnical System Par Excellence

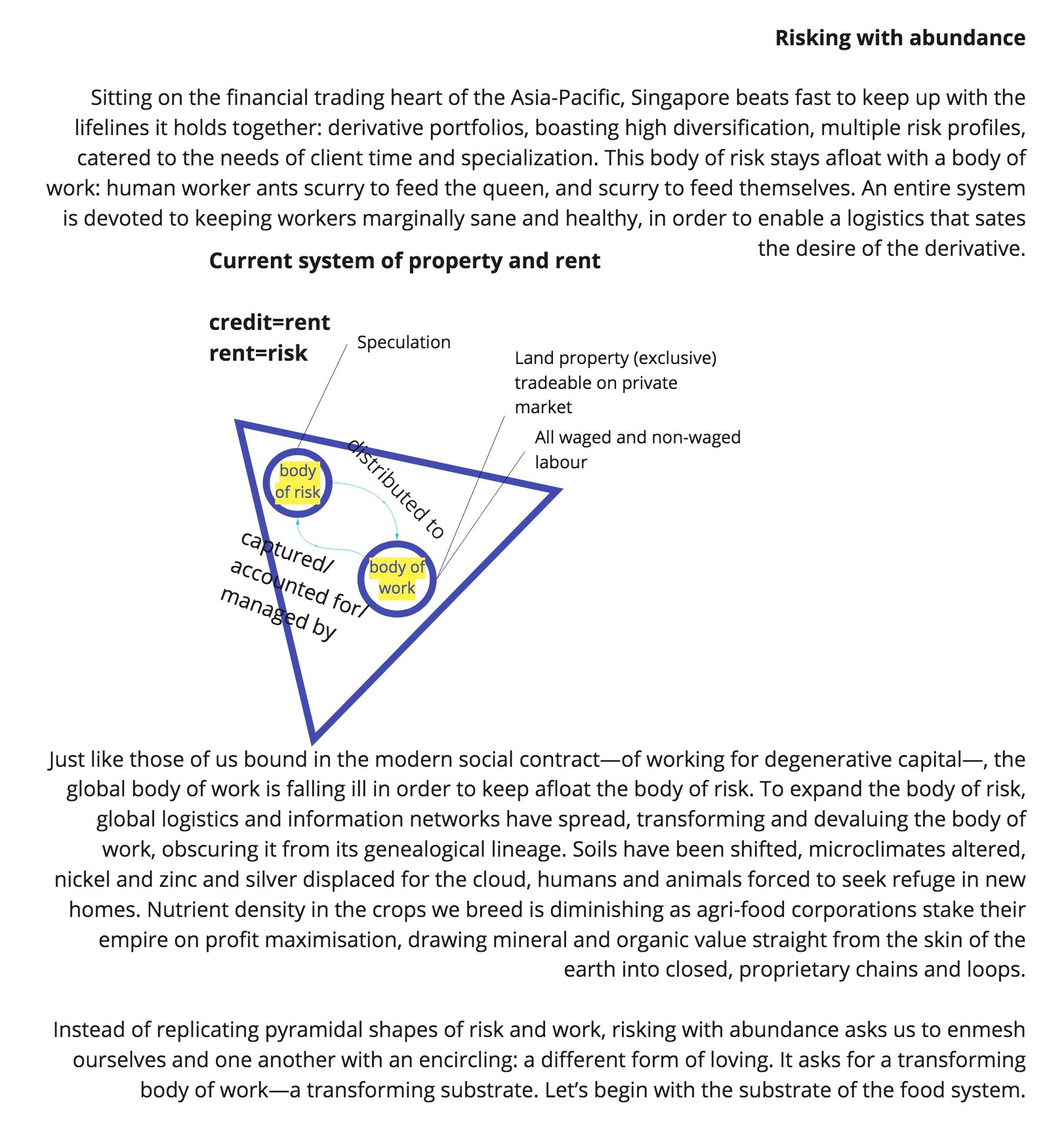

The current food system works to keep its top going. It is not dissimilar to other pyramidal systems of anthropocentric extraction and production. For example, as big data and AI researchers Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler have shown in their mapping of the rare earth minerals that support our technoconsumption today, the top 1 percent of users feed off many undervalued forms of work, from human labor, to plants making food from sunlight, to the geological processes that have shaped and compressed matter into mineral.Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, “Anatomy of an AI System,” 2018 [online] (https://anatomyof.ai/).The pyramid is a useful geometric shape with which to think about this system: a system shaped by accumulated damages and risks, fueling accumulated resources and wealth—based on a cyclic flow of (the product of) work, transformed into resource, transformed into product, transformed into resource… a recursion of broken likenesses,Here I am recalling cultural theorist Lauren Berlant’s phrase, “the convergence of broken intimate likenesses, a prism,” where she describes how a film works with aesthetic representation to reflect the infrastructural rhythm of our time: the unbearability of socially necessary proximity and the need to stay in sync. Lauren Berlant, “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times*,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 34, no. 3 (2016), p. 412, doi:10.1177/0263775816645989.ending sharply at a singular point the size of a needle’s tip.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

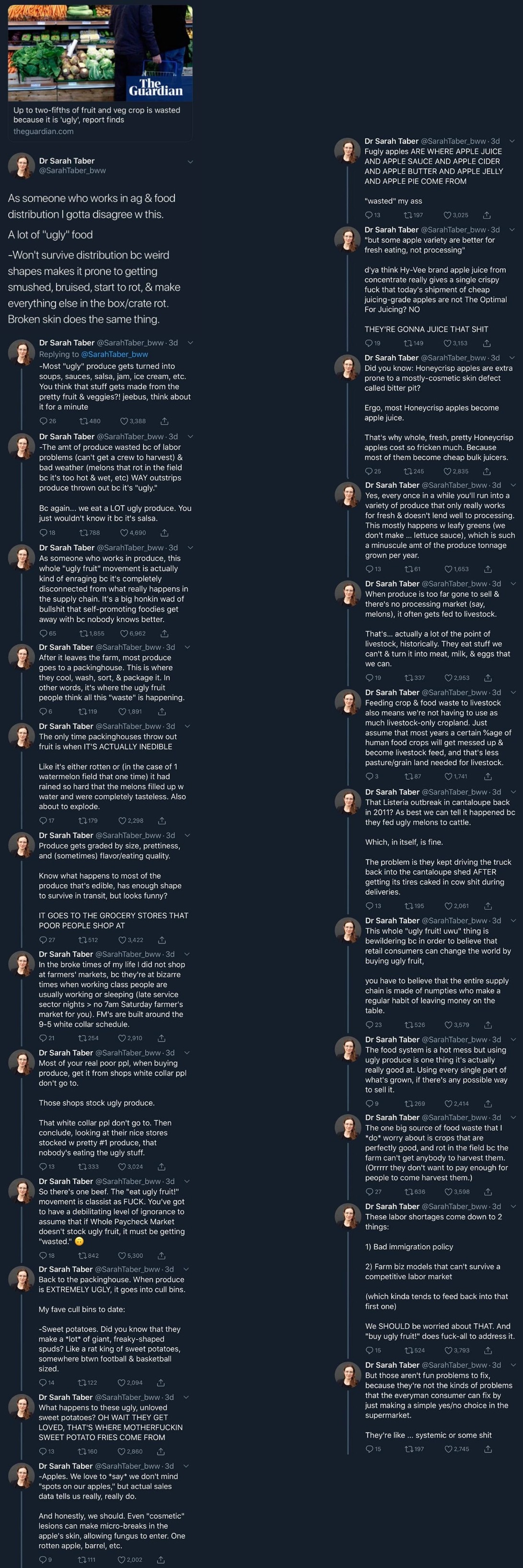

Where total energy in a system stays constant, our current technosphere shapes the human-accessible planet to take on damages and costs to current and future health in order to keep the whole economic system going. Because the planet we have to live off is, after all, only as large or as generous as our abilities to access it are finite, we have shaped for ourselves a very risky system that most of us cannot afford to fail at—in fact, only the ones at the top and the bottom can afford risk. When someone such as the crop scientist Sarah Taber, outraged at the hypocrisy of the ugly food movement, pulls the veil off this risk-laden structure and confronts the bourgeois class with its own ugly underside, the cognitive dissonance can elicit anger, an emotion of defense.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Reorienting from a value-depleting sociotechnical system to a regenerative one is affectively tough—we’re stuck on our habits and industry-supported search for external validation. Reorienting means recognizing how current systems enforce a value-depleting logic that consistently devalues laboring bodies at work, in order to expand the body of risk distributed back to those laboring bodies. Most laboring bodies in capitalism today—an austere, policy-ridden, regulation-heavy, but corporation-driven form of capitalism—accept what enjoyments come their way, accommodating the risks we collectively take to keep our economic engines running. For bodies used to maintaining life against the promise of increased suffocation offered by our current system, reorienting to a better system is not just a logistical issue but a deeply emotional one. Such a system should rebuild trust in connectivity, working to nourish the grain of trust that has been systematically, generationally left to wither.

Like metabolic rifts that detach a chemical or geological cycle from its genealogically coupled cycles, a rift in emotions is likewise a separation: a cut, a detaching incision that divides or bisects, a fragmentation. The bloody wars of India and Pakistan, Israel and Palestine, and the United States in the Middle East, as well as the long shadows of Stalinist and Maoist communism across the world, show us how emotional rifts have a structure of intergenerational inheritance, passed down through unseen, invisible, unintentional lifestyles, reactions, and utterances. These form our social metabolisms with(in) the world.

II. Learning from the Pace of Soil: Growing Emotional Culture

Changing the substrate of our cultures’ emotions—from reactionary to responsive, unaware to intentional—takes place faster than a stone’s pace, but slower than a misdirected turn of phrase. It’s akin to the pace of growing living soil.See Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “Soil Times: The Pace of Ecological Care,” in Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 169–215; and Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity and the Pace of Care,” Social Studies of Science, vol. 45, no. 5 (2015), pp. 691–716, doi:10.1177/0306312715599851. I am talking about a densely-textured soil, generously pocketed with air and protozoa, filled with necromass and biomass.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Soil takes anywhere between three weeks to three months to grow. Making soil is not like making hay. Soil grows through an additive process: addition of biomass, increase of necromass, exponential expansion of microbial activity in the soil. Hay is dried matter, mostly carbon. Soil is variously rich in nitrogen, carbon, phosphates, nitrates, and the nematodes, fungi, and bacteria that fix these chemicals in the soil, keeping them in the soil structure so they don’t leach away.

Growing soil takes care. Cultivation is an art, and a fulfilling one. In giving life, it reciprocates and gives life. A lesser-known fact: despite the heavy interest of the agricultural industry in hydroponic systems in Singapore at the moment, it is precisely these systems’ independence from humans that makes them a setback for food and sustainability educators. In order to teach the ability to care, to cultivate, to be with one another, interdependence is important. Interdependence is life giving, enabling, as it does, the ongoing exchange of gifts. Knowing how to be interdependent takes maturation and cultivation—much like soil, less like hay.

Mediated through the substrate of a gift-less, culture-less hay, our emotional rifts today run haywire, with epic collateral effects. Pain resounds and amplifies through overdetermined, yet structureless, space, colliding with impact and reverberating through the vacuum of silence. Not slowed down but shifted into a different frequency, a sharper pitch, a longer wavelength, a greater amplitude of pain.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

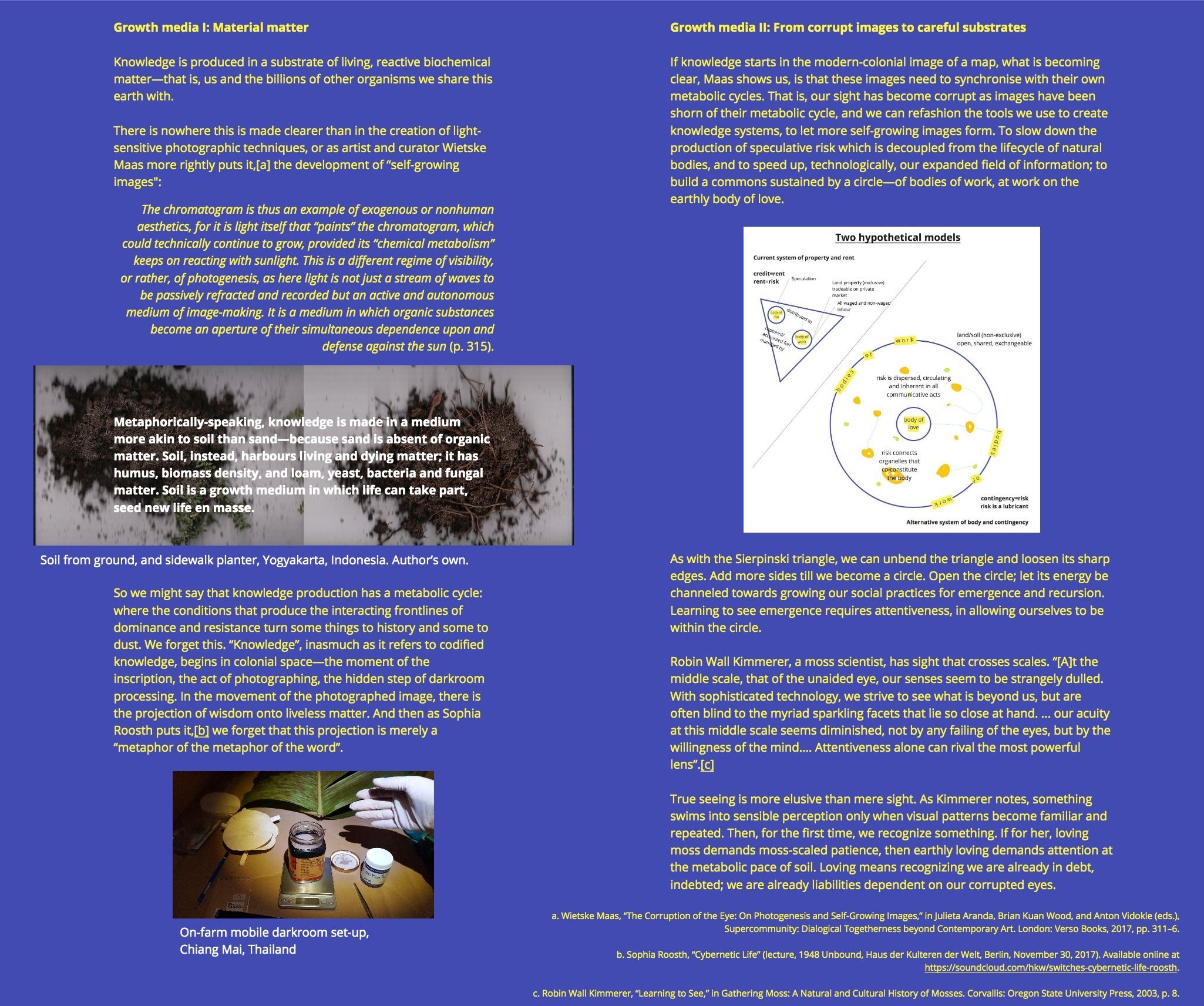

III. Growth Media and State Models: Power, Governance, and Protocols

Technology and social practice rarely receive attention as partnered entities, though the study of sociotechnical systems, as well as science and technology studies more broadly, has more recently emphasized their mutuality.

But technological objects alter as they enter a growth medium, where they begin to dialogue with forms and operations of power, mediated in the diverse substrates of the world. These substrates are neither neutral nor truly capable of absorbing the ideals and principles that the objects seek to introduce. Coming on the tailwinds of global insurrectionary excitement in the early 2010s, we need to acknowledge that speculative futures remain interrupted by the sociopolitical order that mediates their growth, and also that a larger crowd of users does not mean more intelligent decisions, but only that a more complex game can be played.

First, protocols. Scripts or systems enforce modes of behavior that become commonsensical, that create our mental models of the world. As the neurosciences expand our scientific understanding of the human mind, the capacity for capital to bring cognitive formatting into its portfolio—making the design of the mind a product, a service, and an account—also expands. Protocols need not be intentional in themselves, but they provide the backdrop against which all agentic actions occur, and thus how all agents can act. And for better or worse, they “vastly increase the number of actors that can interact,” as network theorist Felix Stalder writes in “The Crisis of Epistemology and New Institutions of Learning.”Felix Stalder, “ The Crisis of Epistemology and New Institutions of Learning,” in The New Alphabet: Opening Days, conference book. Berlin: Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2019.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Second, institutions. People may not intentionally seek to harm or hurt, but the institutions they submit their labor to hold massive institutional power to relay, block, and enable communications, advertising, and the transfer of user data and cognitive formatting. These institutions may consume planetary and socioemotional resources, leaving at best physical and mental traces for individuals to use, for consumption or extratemporal self-care.One example is what I’m starting to think of as the OOTD (outfit of the day)-health-food-body-fitness nexus, which layers organic and raw foods, Instagram, meal prep, psychological discipline, and body fitness into one package. A quick-moving package for quick-moving products. At worst, they make people their labor force for the “public good”—such as a national ideology—with little payoff for workers except in base material needs.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

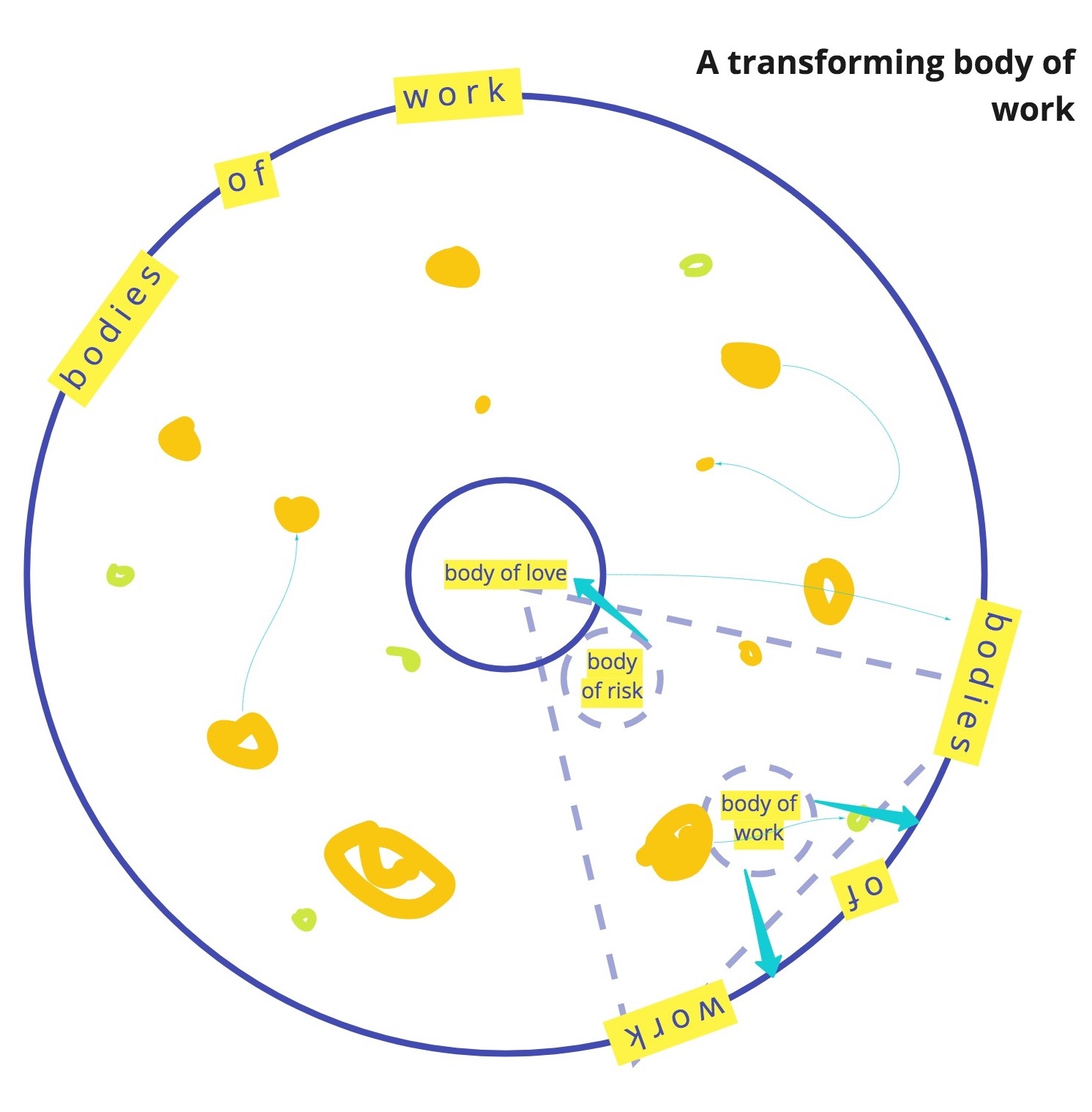

IV. Work, Love, Risk

So, then, to perform an act of love is to work within risk. To build, by facing our interdependence, clearer eyes, sharper sight, and denser, loamier growth mediums.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

We are, after all, strange creatures to care about the Earth. We who, reading this, are statistically less likely to be a person of color or Indigenous, and less likely to be socioeconomically unstable, living in precarity, or poor. We who choose modernity without a care-full look behind, who have little to lose in a dying world, having terminated our roots in the Earth along with our identification with it. We might speak English as a first language, so that our inheritances and injuries are obscured from us. Or, having found our urban spaces and mental reference points deleted on the policy map, as scaffolding goes up to obscure and protect the site of reconstruction, we curse as our inner compasses are thrown off for a week, but oblige the passage of work and its disciplined alignment.

We’ve wrapped our treasures and fled the storm, hiding our eyes as biblical wrath takes care of the fire, the pillars of white sand. And then we try to talk about ecological grief among Indigenous folks, but do not find the words to describe our own suffering.

V. Soil as a Body of Work, Metabolizing the Body of Risk

With the inscription of biblical wrath on the Earth, soil has continued to incur the risk that our loving forces on the world. Inscribed with our love and corrupt vision, the Earth gathers the remnants of our loving’s metabolized products. Can we learn to love differently—openly, rather than guardedly?

Soil is a single organ of the Earth, albeit fragmented as colonized landmass, national resource, a body treated with agro-extractivist colonizing biochemicals. Yet we are already enveloped within the circle of the soil, and we can re-cycle with it. The circle and its metabolic multiplicity is abundantly open to us to share. To enter into community with the soil body, to recognize its astonishing 75,000 species of microorganisms in each micro-biodiverse teaspoon,Elaine Ingham, “Building Soil for Healthy Plants by Soil Scientist Elaine Ingham,” YouTube video, 1:14:49, posted by Diego Footer, May 11, 2016 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzthQyMaQaQ&t=339s). is to reenter the circle, to revisit the sanctified materiality of the tabula rasa—the blank paper, the white cube, the petri dish, the blueprint—and bring it back into the circle, reinscribe it with spiraling growth …

large

align-left

align-right

delete

“The names we use for rocks and other beings depends on our perspective, whether we are speaking from the inside or the outside of the circle. The name on our lips reveals the knowledge we have of each other, hence the sweet secret names we have for the ones we love. The names we give ourselves are a powerful form of self-determination, of declaring ourselves sovereign territory. Outside the circle, scientific names for mosses may suffice, but within the circle, what do they call themselves?” —Robin Wall Kimmerer

All images © the author, if not indicated otherwise.