Aaron Jacobs 2008. Source: Wiki Commons

Container Love, and Fear

The universal standardization of materials, sizes and processes have enabled the technosphere to scale to its present scope, building intermodal infrastructures, logistics and protocols that contour the globe. Journalist and cultural scientist Alexander Klose portends how the blackboxing of global goods and data also opened up a Pandora's box of psychic fears and anxieties.

. . . All either forty or twenty. Standardization. Containers full of merchandise. Packets full of information. No breakbulk.” / “No what?” / “Breakbulk. Noncontainerized freight. Old-fashioned shipping. Crates, bundles. What shipping used to be. I’ve thought that in terms of information, the most interesting items, for me, usually amount to breakbulk. Traditional human intelligence. Someone knowing something. As opposed to data mining and the rest of it. -William GibsonFrom a novel by William Gibson, Spook Country. London: Penguin, 2008, p. 201.

To be modern is to live within and by means of infrastructures. -Paul EdwardsPaul Edwards, “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems,” in Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey and Andrew Feenberg (eds), Modernity and Technology. Cambridge, MA and London, 2003, pp. 185‒225, quote from p. 186.

I. RIDING THE DRAGON

large

align-left

align-right

delete

"On deck late in the evening on the Atlantic. It was quite warm but extremely vaporous. I got fairly paranoid. First a Shakespearean scenery of grey-in-grey in the fog, on the foredeck. Apparitional installations, the borders between ship, sea, and sky almost undistinguishable. Any moment, I expected witches and dead seamen to appear with putrid remnants of flesh hanging off their skeletons. Images of homicides from former days’ sea travels. Then, on my way back, on the small track between railing and container zone, a succession of creeking and squeeking sounds grew ever more suspect. I ventured to the inside to explore where these sounds were coming from. In order to do that, I had to climb a ladder and then walk a runway between rows of containers to the middle of the ship. The crunching and grating got ever louder. Two thick steel panels were erected left and right of the runway, forming a tunnel through which I had to pass. Inside, the noises grew even more intense. As if it was a gateway to another industrial plane. In the middle of the ship there was a container clearing. Yellow digits and metal inserts in signal-red distributed at regular intervals on the grey metal flooring. The moment I entered the clearing, a fan or a cooling system or something of the like started to roar from the back corner. It cost me quite an effort not to flee in panic, but to explore the origin of the different noises instead, recording their sounds with my minidisc-recorder."

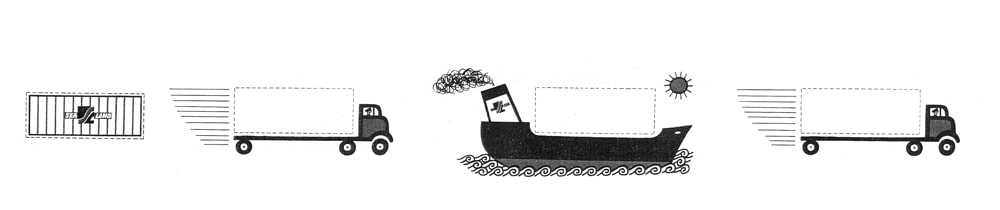

The passage just quoted is from my “logbook,” kept while on a twenty-six-day journey on a containership from Hamburg to Hong Kong in July and August 2001. This journey has marked the beginning of my ongoing preoccupation with the global container system, the process of containerization and how standardized containers have become crucial elements in the formation of the logistical structure of today’s world. Onboard I found myself in an industrial landscape shaped by serial, standardized, rectangular steel elements. It looked a lot like an open-air storage space with a functional, modern eight-story high-rise building sticking out of the container cluster about two-thirds along the way from the rear (stern) to the front (bow) of the vessel. Although floating in the middle of the ocean, the scenery looked much like the corresponding spatial elements on land: the territories formerly known as harbors, though now called container terminals. These are not necessarily located on the coastline anymore, but also inland, along highways or train tracks. As I learned before starting the containership journey, land transportation routes have turned into canals as an effect of the expansion of the container system.A number of publications covering the history, technology, and economics of containerization have appeared over the course of the last ten years. Here are some I recommend (in alphabetical order): Edna Bonacich and Jake B. Wilson, Getting the Goods: Ports, labor, and the logistics revolution. Ithaca, NY, and London: Cornell University Press, 2008; Arthur Donovan and Joseph Bonney, The Box That Changed The World: Fifty years of container shipping – an illustrated history. East Windsor, NJ: Commonwealth Business Media, 2006; Alexander Klose, The Container Principle: How a box changes the way we think. Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2015; and Marc Levinson, The Box: How the shipping container made the world smaller and the world economy bigger. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006. A development that had begun in the 1950s and 1960s was coming into full force by the 1980s and bringing the liquifying dynamic of capitalism into a new, material quality. And vice versa: the legendary and dignified shipping routes of old like the Northwest passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific or the Monsoon passage crossing the Indian Ocean had become “Motorways of the Sea.” The fundamental differences between land and sea leveled out, producing a seamless land‒water network of transport and mobile storage with intermodal standardized steel containers. It was as if the conveyor belts of the Ford Motor factories had extended outside the factory walls, and connected, to form a global production network, the so-called supply chains.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Re-reading notes from my logbook, I start wondering about the psychic and bodily reactions provoked by my experimental field research into the technological realm. The container system forms a hermetic technosphere to which all of us, indirectly at least, are attached all of the time: almost every commodity we deal with in our everyday life is processed, assembled, and distributed through it. But usually we are not aware of this – the fact that most things have been containerized goes by largely unnoticed. So, what kinds of reactions, and which type of questions should be asked after direct confrontation with the basic material elements of the container world? Do they resonate in the more general framework of the theoretical analysis of the container system, the environments, or the forms of subjectivity brought forward by it?

II. YES, BUT WHAT'S IN IT?

Full of desire, the young woman’s hands caress the surface of the massive suitcase standing on a table in front of her.

"What's in the box?" – "Curiosity killed the cat," answers the elderly man, a federal agent, from the back of the room, "and it certainly would have you, if you'd followed your impulse to open it. You did very well to call me when you did."

She moves around the table, nervously. "Yes, I know, but what’s in it?!"

Pulling some papers together and packing them and some files, the man says "You have been misnamed, Gabrielle. You should have been called Pandora. She had a curiosity about a box and opened it and let loose all the evil in the world."

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The woman starts to lose patience.

"Never mind about the evil, what’s in it?!"

But the all-knowing detective in the showdown sequence of Kiss Me Deadly – a film noir classic from 1955A film produced and directed by Robert Aldrich, Kiss Me Deadly. USA: United Artists, 1955. – continues to refuse to tell the woman about the suitcase’s secret or even to open it. Instead he continues to take refuge in mythology: "The head of the Medusa, that’s what’s in the box. ‘And whoever looks on her will be changed not into stone but into brimstone and ashes.’"

We, the spectators of the movie, know why: a very dangerous, radioactive substance is inside it. The content of the secret load doesn’t play any significant role in the film, though, which is more about the thrills of crime and sex than about a nuclear threat or the Cold War.

Lost in thought, the young woman says "whatever it is in that box, it must be very precious. So many people have died for it."

"Yes, it is very precious," answers the man.

Standing up, walking toward the suitcase again and putting her hands around it, she claims, "I want half!"

"I agree with you. You should have at least half. You deserve it [. . .] for all the creature comforts you’ve given me."

The man looks at her with that slight air of arrogance that he’d worn throughout the dialogue. Then he removes the suitcase from her hands and carries it to the table in the middle of the room. "But unfortunately the object in this box cannot be divided."

According to film historians, Kiss Me Deadly operates through the dramaturgical use of a “MacGuffin,” a concept immortalized by Alfred Hitchcock (and used regularly in his films); a “great whatsit” whose primary function was to drive the plot but whose concrete materiality was marginal.Other famous examples from film history are the falcon statue in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (USA, 1941); the suitcase with its glowing content in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (UK, 1994) (with a direct reference to the suitcase in Kiss Me Deadly); or the thirty-nine steps in Alfred Hitchcocks The 39 Steps (UK, 1935). For a classical definition of the MacGuffin, see: François Truffaut, Hitchcock: A definitive study of Alfred Hitchcock. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983.

Ultimately, the young woman shoots the old detective with his own pistol, which was lying on a cupboard:

"Then I'll take it all!"

The man, dying, tries to warn her one last time. "Gabrielle, listen to me as if I was Cerberus, barking with all his heads at the gates of hell. I will tell you where to take it, but don’t [. . .] He shakes his head, Don't open [. . .] the box."

This warning, of course, is in vain, for Pandora must fulfill her dramaturgical role.

The center of excitement of this scene, though, at least for us, is not the beautiful woman but the promising box, the MacGuffin: a closed container onto which we project all our imagination and fear. “There will always be more things in a closed, than in an open box,” the French phenomenologist and philosopher of science Gaston Bachelard noted in his wonderful study on the poetics of space.Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas. Boston, MA: Beacon, 1994, p. 88.

The unopened container stages possibility and calls for the invention of content. Its imaginary stowage becomes desirable exactly because it is out of our reach. This, or it is used as a screen for the projection of fear and paranoia: such as the Container Security Initiative (CSI), launched by the United States government as a reaction to the terror attacks of 9/11. The core aim of this program was to gain information and regain control over the vast streams of transported goods coming into the US via containerships.

Imagine / if a weapon of mass destruction / sitting in a container within the sea cargo environment / were detonated. / This program helps keep that from happening.

So read the captions in a public PowerPoint information presentation about the CSI, published by the US Customs and Border Protection websiteUnited States Customs and Border Protection, Container Security Initiative – 2006‒2011 Strategic Plan [online](http://www.cbp.gov/linkhandler/cgov/border_security/international_activities/csi/csi_strategic_plan.ctt/csi_strategic_plan.pdf), accessed August 12, 2008. in 2006. The security of the (Western) world, as the image of smuggled weapons-of-mass destruction suggests, was threatened by precisely the ubiquitous transport medium that has played a crucial role in enabling the economic growth and welfare of the postwar era. The “black boxes of globalization” had turned into Pandora’s boxes.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

One of the largest economic and techno-utopian enterprises of the twentieth century – the idea of an intermodal global system of transport, spanning oceans and continents, and reducing transportation costs per item to almost zero – seemed to have received a severe blow. It had made possible distributed production processes and largely unrestricted movement, not only of capital, but also of materials and production facilities, paving the way for a new, logistics-based economy. Now its core principle was in danger – the boxes were left unopened. They were treated as black boxes (as in the corresponding cybernetic principle) on an organizational, administrative, as well as at a physical level.

The principle of the black box in the second half of the twentieth century was of central importance in the organization of data, for example, through internet protocols or in object-oriented programming languages, as well as in the organization of physical processes, such as serial production in the factory or transport logistics. The superior efficiency and speed of the container-freight system relative to the methods of traditional cargo transport is largely an effect of applying the principles of blackboxing to both the physical and organizational levels of transport. Technical processing can be restricted to the standardized, procedural handling of one class of objects with similar specifications. The characteristics of loaded goods, ideally, are only of concern at the beginning and the end of the transport process. The same is true for the organization of data through the introduction of standardized loading documents and query protocols.For a more thorough discussion of the principle of blackboxing with regard to container shipping, see Klose, The Container Principle, p. 216ff.

Through the CSI, US government agents claimed to be able to procure knowledge about the content of containers and their data throughout the transportation process, or even prior to the start of its journey. As a result, all international ports with ships bound for the US had to implement certain security procedures, including allowing US government officials to carry out screenings both in harbor and out at sea. In 2007, the US Congress passed a law requiring 100 percent of US-bound vessels to be screened,Jim Abrams, “Law requiring 100 percent cargo screening sets tough standards,” Associated Press, August 22, 2007), US Department of Homeland Security. leading to protests and resistance by both domestic and international businesses. What quickly became apparent was that it was not possible to fully enforce the rules of the new security regiment. Nobody was willing to incur the costs required for investment in new technology, changes to procedures, and the severe handling delays caused by the changes. As a consequence, everybody had to compromise: some technological innovations were implemented while the overall operating mode remained untouched. Thus, the Pandora view won on a number of legs but not in terms of the entire race. Containers still function as black boxes of globalization as the size of container ships has been increasing as have the number of containers being shipped globally. But the Pandora aspect cannot be forgotten: drugs, weapons, hazardous materials, refugees, terrorists, bombs . . . everything that is considered bad or scary – or in any other way problematic – about globalization, has been semantically attached to them.

III. INFRASTRUCTURALIZATION

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Microwaves bounce between billions of cell phones. Computers synchronize. Shipping containers stack, lock, and calibrate the global transportation and production of goods. Credit cards, all sized 0.76mm, slip through the slots in cash machines anywhere in the world. All of these ubiquitous and seemingly innocuous features of our world are evidence of global infrastructure.Keller Easterling, “Introduction,” Extrastatecraft: The power of infrastructure space. London and New York: Verso, 2014.

Far from being either historical novelty or recent development, the fundamental importance of infrastructures dates far back. Roads, aqueducts, canals, sewers, shipping lines, or messenger services were all crucial to the success of cultures, cities, states, and empires from antiquity through to the modern era. Furthermore, the innovations of the nineteenth- and the early twentieth century – the construction of vast networks of railroads, power, telegraph, and telephone systems, followed by the highways and oil pipelines of the petro-cultural eraThe term petro-culture was coined by a group of US‒Canadian scholars who began systematically researching how mineral- and oil-based technologies and materials have formed cultures, politics, and societies over the last hundred years. For an introduction, see Ross Barrett and Daniel Worden (eds), Oil Culture. London and Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014. a little later – still ought to be seen as the heroic, formative years of our contemporary world of ubiquitous infrastructures as described by Keller Easterling in the quote that opens this section. Up to today, an increasing number of large technological systems have become naturalized, largely shaping the environments we all live in today and treat as “second nature.”“(M)ature technological systems – cars, roads, municipal water supplies, sewers, telephones, railroads, weather forecasting, buildings, even computers in the majority of their uses – reside in a naturalized background, as ordinary and unremarkable to us as trees, daylight, and dirt. [. . .] In short, these systems have become infrastructures.” See Paul Edwards, “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems,” in Misa, Brey, and Feenberg (eds), Modernity and Technology, pp. 185‒225, quote on p. 185.

Yet, another decisive conceptual shift has been happening: this began in around the 1950s and had close links to cybernetic thinking and the invention of computers. Initially, what had started at state level –more specifically at the military and then corporate levels, then dispersed. The introduction of the Personal Computer and the emergence of a worldwide computer network (beginning in the 1980s) drew in the individual citizen, the worker, the employee, and all consumers. This development then accelerated, so that by 2000 mobile communication and computing had dispersed to the extent that just about everything that could be digitized is digitized, transforming daily routines into high-speed actions. Today, digital technology has brought the infrastructure closer, to everybody’s life – to people’s bodies and brains – than probably ever before. We have become infrastructured subjects not only when we are using (or are connected to) large technical systems like public transportation or electricity,For the concept of subjectification through infrastructures in general and for infrastructuring through public transport systems in particular, see: Stefan Höhne, “The birth of the urban passenger: Infrastructural subjectivity and the opening of the New York City subway,” City 19, nos 2‒3 (2015): pp. 313‒21 [online](http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015276); for more on the comparison between the development of the internet and the power networks as infrastructures, see Nicholas Carr, The Big Switch. Rewiring the world, from Edison to Google. London and New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009. but also as we are navigating through (and are navigated by) infrastructured space which is almost everywhere.

One aspect of the culmination of the emergent digital sphere – hovering like a gas between and around everything and everybody – is the “internet of things.” Here, the two ubiquitous networks that have been in the process of transforming the world since the second half of the twentieth century and their corresponding processes of digitization and containerization – the operationalization of the cognitive and of the physical world – are coming together conspicuously and inseparably. Logistical systems operate the network of things both at the informational and at the physical level. This interpenetration of computerization and containerization reaches back to the early years of both technologies. The calculating power of computers played a critical role in the development of some of the key elements of the container system. Beginning in the 1960s, it became evident that it was not possible to manage the increasing complexity of container-logistical processes without the help of computers.For detailed historical analysis of the US transportation business, see James W. Cortada, The Digital Hand: How computers changed the work of American manufacturing, transportation, and retail industries. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. On the other hand, the logistical principles that organize the space and processes inside computers and connect their networks are taken from (or at least inspired by) the physical world of transport. It began with the basic (von Neumann) computer architecture with its busses, hubs, and ports; then continued with the leading metaphors for the organization of file systems, desktops, or programs. Then came the container-formats, take a .pdf, .flv, .mpeg or .wave file-format, which allows the mix of text/image, audio, and video content that accounts for the vast amount of today’s data traffic via the internet. Where the digital sphere touches the material world, therefore, one could suggest that most often it comes in containerized form.For analysis of the nexus between containerization and computerization processes, see Klose, “Computing with Containers,” in Klose, The Container Principle, pp. 199ff.

The container system ushered in computerization of the world and the corresponding processes of virtualization on many levels, which later became the logistical-epistemic order in which we live today.

Containers are the main physical and conceptual agents in the diffusion of the economic system we have come to call globalization. In performing both conceptual and physical work, the container forms an infrastructural triangle with the principle of money and the function of computers. Exploring the physical spaces of container transport, therefore, is not only an encounter with the vast dimensions and materialities of one of the most powerful infrastructures of today, but evokes the feeling of paying a visit to the micro-worlds of computing itself as well.