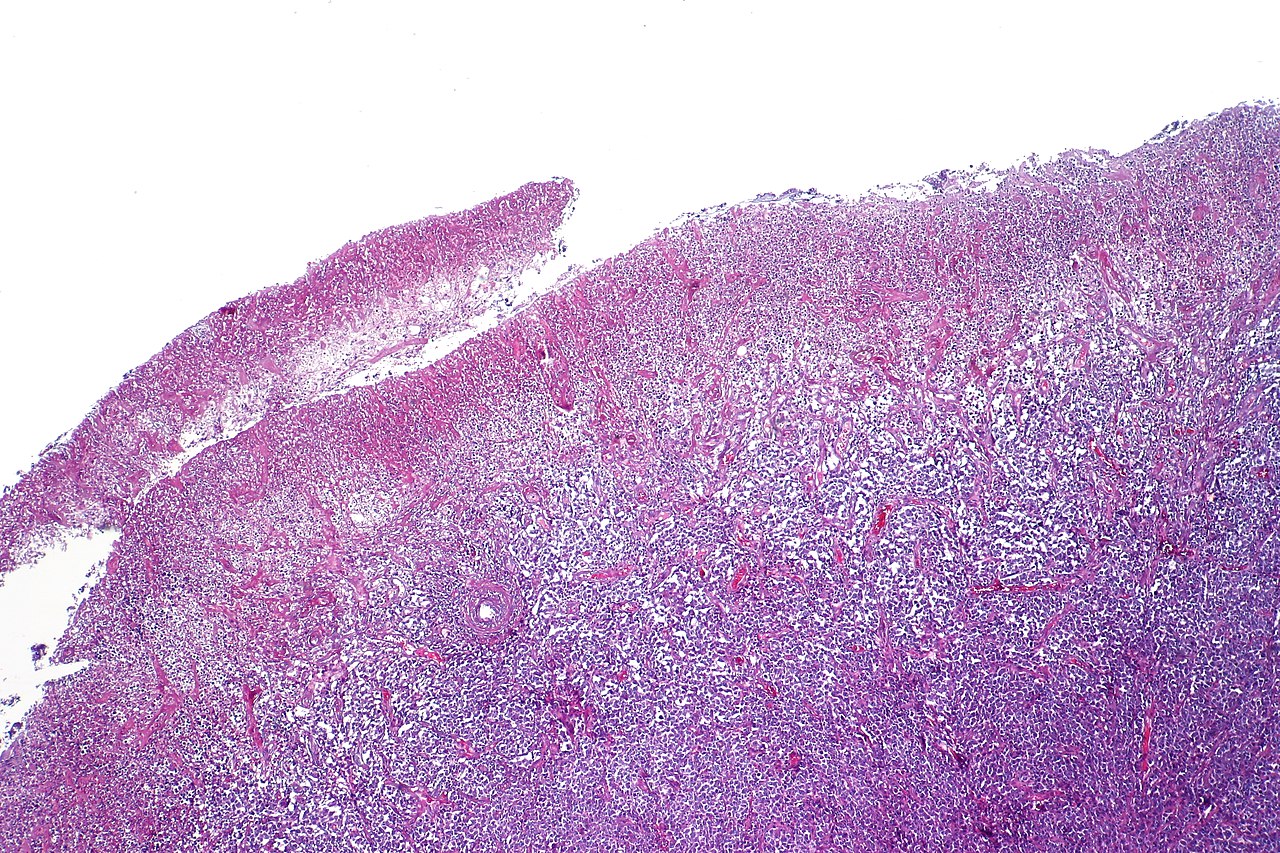

Source: Wiki Commons

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the small intestine.

Anthropocene in the Cell

What does it take for the life sciences to reflect on themselves and their conceptual models in the era of the technosphere? In this conversation, sociologist Hannah Landecker and historian of science Flavio D’Abramo discuss the drastic shifts in our understandings of body-environment dynamics made visible by recent insights within the fields of epidemiology and epigenetics. They point to the necessity of reflecting on the limits of the organism itself, given the ways in which the social, ecological, and multi-species environments are intertwined with the biological one.

A Conversation between Hannah Landecker and Flavio D'Abramo on Body-Environment Dynamics in Anthropogenic Times

Flavio D'Abramo: I would like to open this conversation about social science and contemporary biology by discussing studies made in open ecological contexts that show the continuity between organisms and their environments. These studies show the necessity of bridging the nature/culture dichotomy. In some species belonging to the goby, wrasse, and bass groups of fishes, for instance, the meeting of counterparts can change sex determination, a process that is mediated by the fish’s senses, which in turn control hormones, which in turn regulate the expression of genes, which in a few hours coordinate the transformation of sexual physiology. In these fishes, environmental and social factors trigger a change of the body itself. In animal and plant kingdoms, there are plenty of examples that reveal the high plasticity of organisms as shown in developmental biology and epigenetics.Mary Jane West-Eberhard, Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003; Eva Jablonka and Marion J. Lamb, Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005; Scott F. Gilbert and David Epel, Ecological Developmental Biology: Integrating Epigenetics, Medicine, and Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2008. For instance, there are butterflies whose coloring and size depend on the season in which they are born. Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, classified two of these butterflies into two different species (Papilio levana and Papilio prorsa). Some decades later, the entomologist Jacob Hübner recognized that these two butterflies that Linnaeus had sorted out into two species are just one species that develops different colors and sizes. Linnaeus thought of nature as a quite fixed expression of dynamics, and he ignored the key role of many environmental factors.

Hannah Landecker: He was thinking of a stable environment.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Flavio D'Abramo: Exactly. Similarly, the lower jaw dimension of humans is determined by the solidity of the food chewed during the first years of life. The mechanical action of jaw muscles activates a feedback loop involving genes that coordinate bone growth. But the most striking case that shows the dynamicity of the biological world is that of bacteria and the relationship between them and us. We each host a microbiome, and this ecosystem shapes both physiology and function.Thomas C. Bosch and David J. Miller, The Holobiont Imperative. Perspectives from Early Emerging Animals. Wien: Springer, 2016. This fact is true for most of animals and plants, and in mice, for instance, there is a bacterium that lives in the gut and coordinates the formation of intestinal vessels by regulating gene expression. In humans, other bacteria coordinate the formation of lymphocytes called helper T cells, a fundamental part of our immune system.

Hannah Landecker: I think in each of these cases, it is instructive to ask: Why am I surprised by that explanation? Why is it surprising that resident bacteria are essential to determining intestinal physiology? Why is it surprising that seasonality can be so integrated into development that it produces a body form that looks like two different species? Why do these cases push up against the structures of expectation that we have? Epigenetics and microbiome science are interesting in and of themselves, but they are also a useful reflexivity tool for delimiting the structure of thought. These new forms of scientific explanation are like a biological stain—you put it on a cell, and it reveals the structures in the cell. Thinking through epigenetics stains the conceptual apparatus, and all of a sudden, it shows quite sharply how things are categorized, such as expectations about what’s inside and what’s outside an organism. Although researchers often use epigenetics and the microbiome to try to understand disease, these sciences show us that all development and ongoing life are in a constant process of transduction, incorporation, and adjustment of what we’ve traditionally thought of as being “outside” of organisms. In fact, if “environmental” input didn’t exist, there wouldn’t be a being at all.

Have you seen the recent paper led by Yun Teng from Huang-Ge Zhang’s lab that shows that exosomes containing microRNAs in foods such as ginger are preferentially taken up by certain species of gut bacteria, where they participate in bacterial gene regulation?Yun Teng, Yi Ren, Mohammed Sayed, Xin Hu, Chao Lei, Anil Kumar, Elizabeth Hutchins et al., “Plant-derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Shape the Gut Microbiota,” Cell Host & Microbe, vol. 24, no. 5 (2018), pp. 637–52. In modulating bacterial life, they also affect the gut-barrier function of the host animal. This is exactly what I mean by “a surprising result” that shows how we have thought—in this case, about the inertness of the matter we ingest. Now we see that plant matter informs (not just feeds) bacteria, which in turn inform animal cells that shape the very physiology of the barrier between the gut lumen and the body. It is a bit hard even to say what we will ultimately consider to be “the environment” in this scene. The plants? The bacteria? But the body is the environment for the bacteria and the interface between body tissues and gut microbes is clearly dynamic; they are embedded in one another.

Flavio D'Abramo: It seems today we are experiencing a welcome disruption of expectations we have about the dynamicity of organisms. Our thought has been molded by cases of disease or situations in which developmental trajectories of animal growth have been altered by chemical substances that mimic hormones (also known as endocrine disruptors) released in the environment or by other environmental conditions. Some plastics used for food packaging, herbicides, and the increasing salinity of drinkable water exacerbated by higher sea levels deviate the development of the organs of animals, humans included. Aneire Khan and Paolo Vineis, epidemiologists with whom I’ve been working in London, have shown that the salinity of drinkable water caused by climate change determines the onset of salt-related pathological conditions such as hypertension, eclampsia in pregnancy, and cholera outbreaks.Paolo Vineis, Aneire Khan, and Flavio D’Abramo, “Epistemological Issues Raised by Research on Climate Change,” in Phyllis McKay Illari, Federica Russo, and Jon Williamson (eds.), Causality in the Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 493–501. Disciplines such as ecological developmental biology, established recently by Scott F. Gilbert, show us that most of the characteristics of organisms, human health included, originate and are preserved within the encounters with other forms of life such as bacteria. Think, for instance, of the biological history of mitochondria described by Lynn Margulis or horizontal gene transfer studied by Carl Woese and W. Ford Doolittle.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

I’d like to turn now to the implications of the new organism-environment thinking in the context of the Anthropocene. In fields that involve massive interventions toward humans or animals—for instance, biomedicine and food production—substances are produced, intentionally and unintentionally, and then put on the market. In recent studies, I have shown how the disruptive use of chemicals and disruptive behaviours have an impact on both human biology and our way of thinking and planning, as well as on scientific research.Flavio D’Abramo and Danya F. Vears, “Health, Wealth and Behavioural Change: An Exploration of Role Responsibilities in the Wake of Epigenetics,” Journal of Community Genetics, vol. 9, no. 2 (2018), pp. 153–67. Some by-products of mining such as arsenic have been put on the market as antiparasitics, which have allowed intensive livestock growth and the flourishing of some billions of humans. But out of these processes, antibiotic resistance and a severe deterioration of the environment have also arisen. In your own research, Hannah, you have shown how a capitalist ecology is created out of these processes.See Hannah Landecker, “Antibiotic Resistance and the Biology of History,” Body & Society, vol. 22, no. 4 (2016), pp. 19–52; and Hannah Landecker, “Trace Amounts at Industrial Scale: Arsenicals, Medicated Feed, and the ‘Western Diet,’” in Angela Creager and Jean-Paul Gaudillière (eds.), Risk at the Table,forthcoming. Industrial processes have grown in scope and beyond the frame of intentionality. So it’s like our societies have lost the capacity to control what’s happening on a larger scale, even as we realize the importance of the environmental scale.

Hannah Landecker: Well, that is, if societies ever had such control. For me, the concept of the biology of history in my work on antibiotic resistance really came from realizing that in one timescale, you can have control—for instance, in the immediate present, you can control infectious disease quite well.See Landecker, “Antibiotic Resistance and the Biology of History.” Antibiotics were very effective in this regard. Yet at the very same time, through the very same actions—but in a different timescale—you’re losing control in the form of rising resistance. It’s just that the first trajectory is located in a scale of immediacy, of treating this patient in front of you right now. The other is unfolding on a longer timeframe and at a different scale. Thus you can simultaneously successfully treat the patient in front of you and drive the dynamics of antibiotic resistance. We tend to think of things as working or not working, having control or not having control, but maybe it’s not so clear-cut. Thinking of those two outcomes as simultaneous and unfolding in the form of biological consequences—particularly in light of the sciences we discussed just now—is quite helpful. What kind of biology, or biologies, are forming now? There are a number of people thinking about the fact that we can’t say that our current situation, with its pervasiveness of anthropogenic chemicals, is an aberration that if corrected would simply return us to a prior state of purity. Take, for example, Alexis Shotwell’s work Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times or Michelle Murphy’s idea of “alterlife”; both point to anthropogenic change, chemicals included, as integrated into kinship and development, as now part of us and human reproduction.Alexis Shotwell, Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016; Michelle Murphy, “Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 32, no. 4 (2017), pp. 494–503. If we’re going to think with the inextricability of organisms and environments at mind, then it seems clear to me that the Anthropocene isn’t just about climate change that affects organisms downstream. Rather, there is a historically unfolding biology of this world at this time—an Anthropocene in the cell, if you will, right down there in the topography of epigenetic chromatin modifications and microRNAs. So this may be a depressing thought, I guess, but it also seems more realistic as a way to think about anthropogenic influence in terms of biology and society today. The social environment has a physicality to it when things such as crowding and stress play such a central role in disease and development. Likewise, the physical environment is also socially formatted, in terms of the distribution of chemical, nutrient, and polluting matter. It is in these terms that we might need to discuss control, or lack thereof.

Flavio D'Abramo: I hear what you are saying, but at the same time, in scientific studies focusing on epigenetics of trauma and stress, there are some models for returning to a normal epigenome: re-establishing the equilibrium after trauma, intoxication, violence, a forced migration, an experience of war or famine. Often, these are molecular therapeutics designed on the principles of chemical characteristics of histone proteins, for instance, and they assume that the system can be reset back to its previous, pristine state. This seems to be exactly the opposite of conceiving nature as an interrelated network of organisms. So this is what puzzles me: How are older models that assume control of bodies or diseases by manipulating a few molecules important for gene expression still so powerful, even in the heart of a scientific framework that seems to speak against that possibility? Is it conceivable to shift knowledge production to activate more self-reflection? Is science capable of looking at itself and the models that have proven to be wrong?

Hannah Landecker: Maybe. Scientists themselves are quite good at understanding that if you identify hidden assumptions, you often produce innovation or a surprising finding. There’s a sort of auto-critique built into the competitiveness of science, in the form of looking for questions that other people haven’t asked. Nonetheless, the pressures of specialization and productivity in the sciences can make it hard for people to think about assumption structures or compare sub-disciplinary perspectives

—Gosh this is how it works in epidemiology, but this is how it’s working in evolutionary biology.

I could make a joke that we should be developing a “reflexivity pill.” Maybe we need to dose everybody with the “reflexivity molecule” so that they take that mode of thinking into their work every day. But seriously, it’s about more than just how people think. It’s also about what is happening out there in the world, to bring it back to the question of biology in the Anthropocene. The materiality of the world pushes on scientific and biomedical explanation as well. Explanations that really fail to account for phenomena or fail as interventions in the face of, say, metabolic disorders or antibiotic resistance will be easier to dislodge. Sometimes, once an alternative framework is visible, we see very quick change—as we’re seeing in the rise of the microbiome and its legitimacy as a form of explanation. It’s been kind of astonishing, the shift away from twentieth-century bacteriology—focused on pathogens, one species at a time, pure culture, Koch’s postulates, and all of that—toward a viewpoint that employs a much more ecological and multi-species framework. But science is noisy, and connected to all kinds of other forces, so you are never going to see just one approach at work when you are talking about developing molecular therapeutics.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Flavio D'Abramo: There’s this idea that technology via industrial production shapes society because we live in a technosphere, a place in which technology modulates our lives. So there might be some inquiries into societies that could be understood through the lenses of interdisciplinary research, going through different levels of different phenomena. But this interdisciplinary approach is hindered by specialization. However, some disciplines, like genetics and epidemiology, help the meeting between different disciplines. This interdisciplinary take can mobilize a knowledge useful in understanding the scope of the interrelations among organisms, their individual and collective behaviours, as well as the historical clues within and outside organisms. In this case, history is one of the best disciplines to understand interrelations and interactions.

Hannah Landecker: In The Division of Labor in Society, Émile Durkheim comments that

general culture, once so highly extolled, appears to us [in the late nineteenth century] merely as a flabby, lax form of discipline.

By contrast, in societies in which the division of labor had become widespread by this time, such as France,

we perceive perfection in the specialist, one who seeks not to be complete but to be productive, one who has a well-defined job to which he devotes himself, and carries out his task, ploughing his single furrow.Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society, ed. Steven Lukes, trans. W.D. Halls. New York: Free Press, 2014 [1893], p. 35.

So in 1893, Durkheim was seeing the scientists around him in this way—each man ploughing his own furrow, going deeper and deeper while building higher and higher berms of earth on each side, making it ever more difficult to see into other furrows. It was an image that made sense at the beginnings of sociology, as well as during the formation of other disciplines such as biochemistry or genetics, or even agricultural chemistry, which was all about increasing the productivity of furrows! I’m afraid this is our intellectual legacy through our inheritance of disciplinarity—and it is really important to recognize how understandings of productivity come to us from a historically specific moment in Europe and the nineteenth century. I don’t mean by this that we need to abandon the idea of productivity and not have a discipline of sociology, or abandon endocrinology or any other way of designating a domain of expertise that came into being in that period. Yet it can be very powerful to understand the historical specificity of these knowledge formations. I think this is a very helpful way to conduct any inquiry, our own included. History as the “reflexivity pill.” Maybe it will help us digest the technosphere.