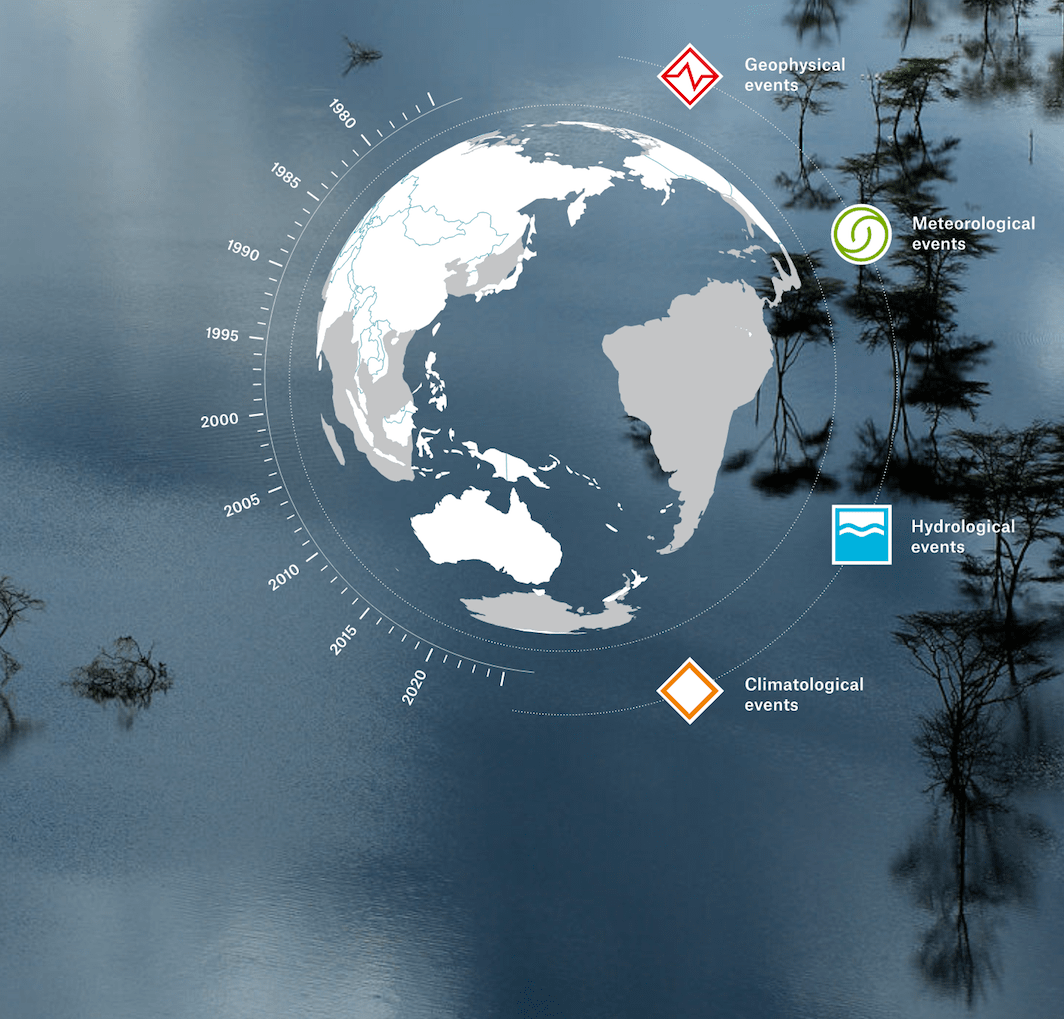

Munich Re, 2017

NatCatSERVICE analysis tool

Impacts and Insurance: Climate Change Risk Transfer

Is a creeping catastrophe insurable? Eberhard Faust, climate risk researcher at Munich Re, one of the world's largest reinsurance companies, and disaster historian Scott Knowles talk about the instruments and scale-problems involved in calculating and transferring the costs of climate-change-related events on the ground.

Scott Knowles: In February you were at the German meeting of climate experts in the context of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In view of that state-of-the-art discussion, what are some of the projects taking your time right now, some of the most exciting developments recently in climate research and around development of instruments to deal with climate change?

- Eberhard Faust: A major development in recent years is the emerging research literature on attributing the damaging magnitude of single events to climate change as a partial cause. This attribution can be achieved for a specific event by applying climate models which simulate the variable of interest, e.g. a three-day rainfall sum, for the relevant season and region, both without today’s influence from climate change and with this influence, in each case for a representative period of model years. Comparing the two distributions of rainfall sums achieved by this approach, it can be inferred how much the probability for the given extreme rainfall event has already changed relative to a virtual world without climate change. For example, the extreme precipitation with subsequent flooding in Louisiana in August 2016 which led to 10 billion US dollars in overall losses was found to be a thirty-year event in the central Gulf Coast region and has increased in probability relative to a world without climate change by at least a factor 1.4. This methodology is, I think, quite evolved now. The only drawback, as of now, is the selection of events being done subjectively. As a representative of my company, I’m involved in a project as a stakeholder which is focusing on Europe and this project would like to come up with an objective selection of such events, at least in the long run. If in the aftermath of a disastrous event the reliable knowledge of climate change as a cause, however partial, of altered frequencies or intensities of such events can be established, this information would entail two consequences: firstly, it implies that according to the dynamics of continued climate change in many cases the frequency of such extreme events will likely even further increase in the future. Secondly, this service of rapid attribution in the aftermath of an event will lend maximum momentum to local authorities and others to implement adequate adaptation measures. So these approaches on “rapid attribution” are exciting, I think.

Scott Knowles: So right now, is it just limited to rainfall events?

- Eberhard Faust: It’s basically temperature and rainfall ‒ it is here that these methods work best. In some cases other variables have been dealt with, but foremost are temperature – mainly heat – and rainfall ‒ including lack of rainfall which is called drought. Since 2011 far more than a hundred such studies have been published and some 65 percent of them were able to show that climate change was in some way involved in those events.

Scott Knowles: When I looked at Hurricane Katrina from the perspective of emergency managers and what they were trying to understand about what had gone wrong in infrastructure systems and the like, one of the key findings was that there was a failure in communication to motivate people to leave. Every individual and every family had to make decisions in a short period of time about what to do because leaving also incurs a cost. I think there is a metaphor here more broadly for climate change discussions ‒ staying a certain path has a cost and leaving and changing the path has a cost too. So individuals in New Orleans had to make that decision. And as researchers looked at it, what they found was that fear was not the only motivator, in fact fear is, of course, very perspectival, very personal, but fear operates at different scales. You may be afraid of something happening right now, but other fears may be something that you worry about happening in the future, or something that’s in the past.

Fear is not a single substance to be reduced. The better frame was trust.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

And this is what they put a lot of emphasis on, and what I want to get your reaction to: individuals in New Orleans did not trust government, they did not trust the police, not to mention science, and by extension they also did not trust weather forecasters. It came down to a question of who in the community could we have as an interface between experts and the public. Experts might have very esoteric knowledge, very important knowledge, but who will serve as sort of interlocutors or trust agents to communicate to a broader public what you really need, that this is real, that this time it’s very important. Some of the conclusions I came to were that it was pastors, ministers in the church, local people, local politicians – not state or federal politicians! Often it was a matter of “did you know someone,” which is a very hard thing about climate change adaptation and mitigation. It will not be possible for you to go and meet with all 320 million Americans, right? We have to find agents of trust if you buy into this construct. Lobbyists such as the American Petroleum Institute figured this out a long time ago: rather than going after scientific data and scientists per se their angle for some time has been to say to the public: “You do not share the same value system as these scientists, these scientists are not trustworthy.” So it’s not an argument about whether this is true and that is true, it’s much more an argument about trust and I wonder how you feel about that and how it plays back into this discussion around communication of climate science findings?

- Eberhard Faust: There are different layers. If you are immediately involved in a catastrophic event, this is something very different from communicating climate change. In the public perception it is not yet clear to what extent the planet is already affected by climate change, and only future scenarios project truly severe impacts on a global scale. Compared to this global and long-term framework, the perspective was quite different with Hurricane Katrina, because as soon as you are involved with a catastrophic event you know there’s harm already under way, and you have to react in the most efficient way, with fear pushing adrenaline levels up. Additionally of help are the trustworthy people who have a kind of lighthouse role and can tell you what should be the next step. Since archaic times we human beings have been keen on knowledge about imminent catastrophes and responses to disaster, and this attractiveness of catastrophes is likely rooted in our evolution. It was always an advantage for survival to get those early indications that things could flip in a second, that there might be danger around the corner. Part of this fear-based attention addresses people who are deemed to have an overview due to their institutional setting and can help us escape calamities. However, this kind of mechanism could also deceive us. There are different time scales involved with climate change and rapidly unfolding disasters, so this type of fear is not a form of valid guidance for this context. A more adequate approach to climate change has two sides. One side is a sense of urgency because it will affect our children even more than us, so it is a matter of concern that falls within the medium- to long-term future of development. The flipside of this concern is an effort to understand the ongoing processes which will enable us to find strategies to adequately respond and aquire the facts that motivate those responses.Trustworthy communicators of these items – concern and corresponding facts – are necessary, and there are institutions which have a lighthouse role within society for guiding this communication. For instance, I think of business, trade unions, professional associations, and many other societal groups which are and should be involved here.

Scott Knowles: Thinking again about the need for trusted actors, you know, I’ve thought a lot about the role of the insurance and reinsurance industry broadly and also the military in different countries and I think you could also include the agricultural sector, at least in the United States, which is drawn to a very small proportion of our economy and yet culturally has an outsized importance ‒ farmers are still held up, they know the land, they are trustworthy, they have a sort of commitment over long generations. Politically they are not easy to generalize as left or right, there is a sort of separate category for them. The reason I talk about these three, or think about them is because one of those sectors has to take the long view within our society. These are sectors that have made commitments to very forward thinking, looking at least a generation ahead. I also wonder if there’s some way to think about leveraging the cultural power of the insurance and reinsurance industry ‒ in some ways you’re in the sort of restraint business: think about the military, when it's not at war the military is often also in the restraint business; it’s about thinking over things that can go wrong over long periods of time and to prepare.

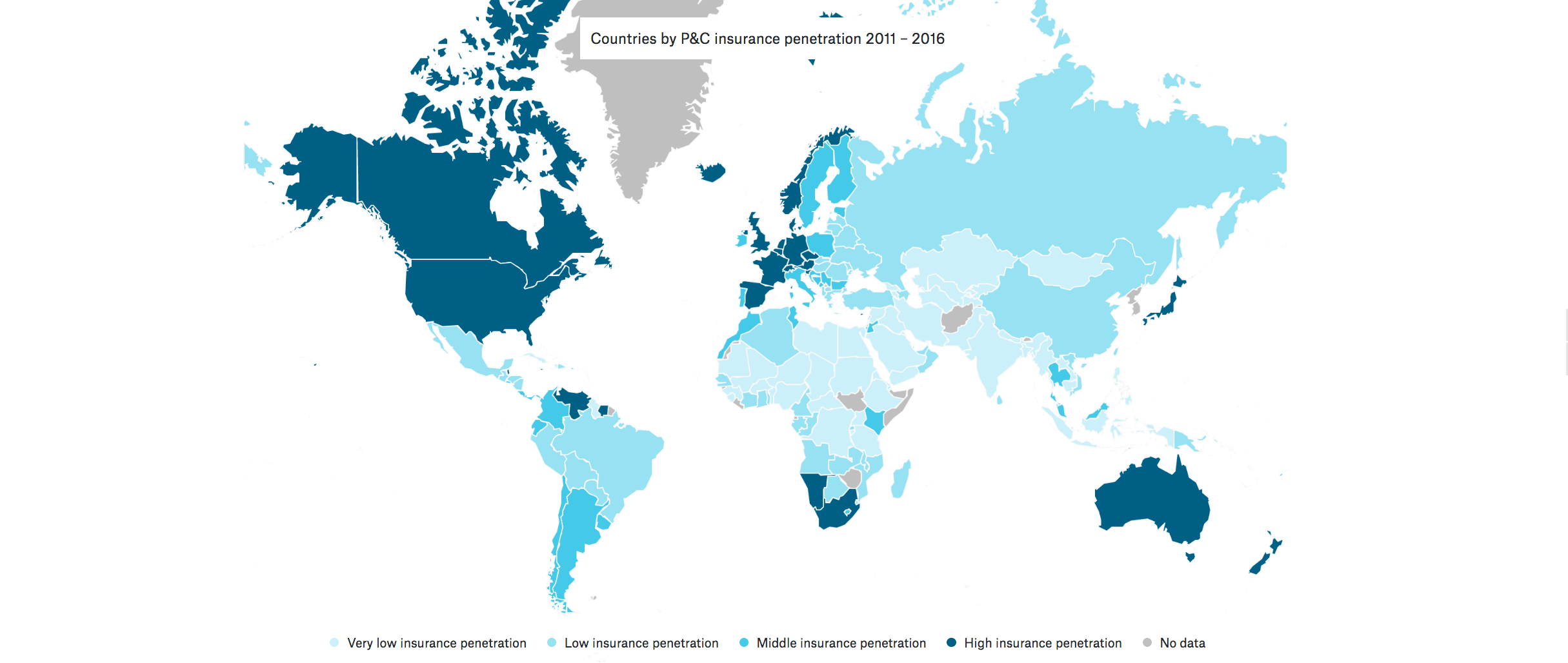

- Eberhard Faust: The business activity in the insurance or reinsurance industry is more on the short-term time scale; for instance, reinsurance covers are renewed annually. However, regarding risk-transfer solutions in the context of adequate responses to climate change, insurers have also got longer term perspectives on their radar, aiming at sustainable solutions. Sustainability is close to the basic idea of insurance, which is to internalize catastrophe-risk costs in advance of catastrophic events, and thereby to make sure that in the aftermath of a catastrophe income, consumption, and economic activity can continue. It was proven empirically by studies that when you have a substantial share of insurance in the overall natural catastrophe-risk financing of a certain country, then you are better off in terms of the GDP, debt status, and other macroeconomic variables in the years following big natural catastrophes. However, there is a lot of concern about developing countries. The problem is that after disasters, developing countries, which do not have a substantial private or public insurance sector, almost completely rely on donor assistance, external credit, and on rededication of portions of the governmental budget. All of this might not be that reliable, might be late, for instance in terms of donor assistance, and might not be sufficient. And this explains the financial gap hampering sufficient ex post-risk financing. Regarding this gap, the buildup of insurance markets in developing countries per se can be seen as an adaptation means to – possibly increasing – natural disasters. This role for insurance-based risk transfer has a structural, medium-to-long-term component which may counterbalance climate change risk impacts. This is deemed necessary, because impacts from continued climate change in the future will worsen still more the aforementioned financial gap.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

- One particular interesting insurance activity in developing countries in recent decades is the emergence of trigger-based or index-based insurance concepts. This means you have a weather-recording station and if a critical threshold at the rain gauge instrument is either exceeded or the index falls below the threshold, then damage is assumed and the payment is triggered. Such a scheme has a lot of advantages. One advantage is the rapidness of this payment, because it avoids time-consuming and also costly loss adjustment. You have also disadvantages, because if the farmer is affected, for instance by drought, but the weather recording station is not correlated well enough, meaning that the rain index was not falling below the threshold, there will not be a damage compensating payment. This will constitute distrust in the scheme, and this is a big problem. This problem is called “basic risk.” But there are improvements available. For instance one improvement is to apply the index not only to individual farmers but to aggregate portfolios, for instance credit portfolios of rural banks granting loans to farmers which they cannot pay back as a consequence of damaging events such as drought. In this case the correlation between losses somewhere within the portfolio and the weather index is much higher. Another means of improvement would be to start from a sample of yields within a larger area and to measure the deficit in terms of yields in this way. Or to use satellite instruments to measure the vitality of the pastures for herders in Africa. Such index-based covers are on the rise and are an important means of risk transfer for developing countries. In the context of such ideas, one should also name a recent major initiative which you might have heard of: the “InsuResilience” initiative which was launched by the G7 in 2015, in Elmau, to insure some additional 400 million people in developing countries against losses from climate-related events. In this context the entire range of instruments that insurance can provide is involved. There are already new pools in existence, for instance the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), which pools natural catastrophe risk of Caribbean states based on index concepts, and there are other similar approaches, such as the African Risk Capacity (ARC) or the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI). These institutions aim at more sustainability and resilience for the respective societies by new means of risk transfer and risk finance products. There is also an inherent idea of longer term adaptation to climate change impacts involved in such approaches.

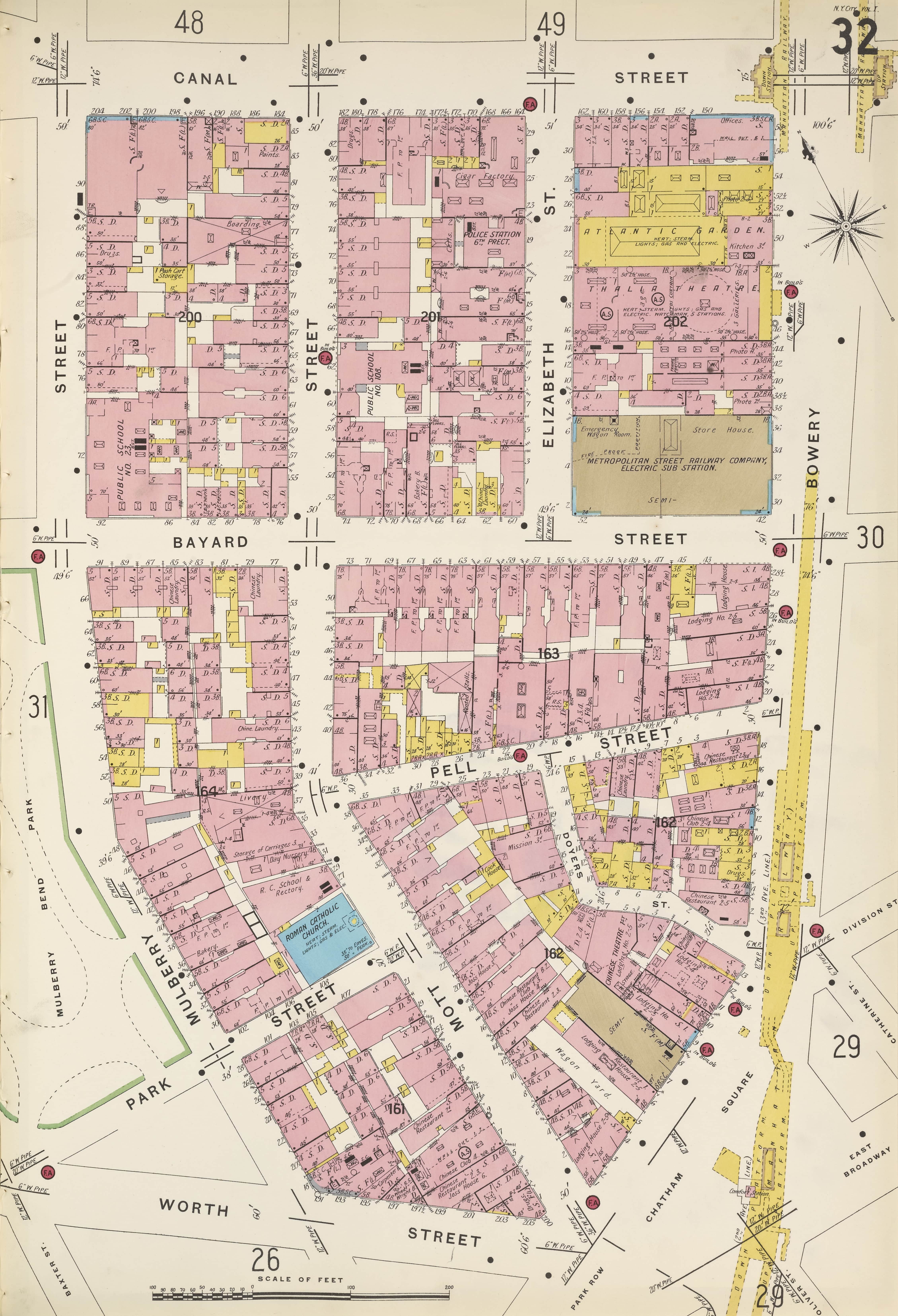

Scott Knowles: What you were describing in terms of sustainable insurance solutions is something I studied in the American context. And historically, what you were saying on public-private arrangements must be emphasized in that there are times at which the scale of problems goes beyond the capacity of governance. That doesn’t mean that governance doesn’t catch up. But you know, 125 years ago, there were peers, people who did the equivalent of what you do today, but they were doing it around built systems in urban spaces and they were concerned about fire, or they were concerned about water quality. And they turned to private instruments to assist them across a gap, a period of time when government and the scale of a problem had gone beyond the capacity of government to achieve real change democratically.

Fire insurance itself was important in reality, but what was more important was the infrastructure that had to be developed to allow that market to thrive.

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

And that meant many different inputs of information, new professions: fire chiefs, fire marshals, the forest service; and what happened over one generation in the United States – it also happened in Germany, Britain, and France – is that this sort of private information, which individuals wanted, to have the insurance work, then worked its way into governments in the sense of having codes and standards and various other things. And I think there may be some interesting parallels to make here around developing countries, where people may not have the ability in Bangladesh, for example, to rely on the government to engage meaningfully in some of these efforts, global government efforts to try to bring about mitigation or sustainability, but they may be able to rely on the insurance industry or also on private sector trade organizations, which have been very very active in trying to shape extraction, in trying to shape forest management with insurance, and the various things you’re saying. When I’ve talked to some of my colleagues about this before they say, “Well you’re very right wing, to have faith in these private instruments.” And my response is that it’s much more complicated than that. We have to look at this as a process where there are new risks created, and government is not always capable, particularly under democratic systems. China can make changes very rapidly within society. In a free democratic society, government doesn’t work that way. It takes time to catch up, to apprehend risk, and to make social society-level changes, whereas the reinsurance industry, or in a private forest-management consortium, they can be much more nimble. And I think that’s worth our consideration ‒ the history and evolution of risk knowledge not as singularly public or private achievements ‒ this history could be equipment, so-called, for this time.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

- Eberhard Faust: This whole field has many facets. Definitely, there is also a public-private partnership involved here. In economics, there was a kind of theorem which was explained by Arrow and -Lind in the 1970s, saying that states or governments do not need insurance, because disaster risk is seen as small compared with a government’s portfolio of diversified assets, and therefore such risks can be borne publicly. But this theorem does not hold anymore if applied to relatively vulnerable small-sized developing countries. This is something that really came up in the discussions, and it was also dealt briefly with in the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC on climate change adaptation, because if you think, for instance, of small island states or other countries where the GDP is foremost in the sectors of agriculture or tourism, there would hardly be found a loss-compensating portfolio of other assets in the aftermath of a climate-related disaster. Perhaps it’s almost only agriculture in some cases. For those countries it will make sense to engage in souvereign insurance or respective pools. This was one of the reasons for forming the CCRIF and other similar approaches in the field of small states or developing states. In other cases, there is an interest in risk transfer and it might be sponsored also by the government in order to improve agricultural output and to allow for more high-yield cultures or cultivars. Risk transfer is a very old thing. If you think of African villagers, it was more usual for those living close to the river, if there was a river inundation, to be supported by relatives from villages inland that had not been hit by the inundation event. The inlanders would stay for a couple of months to help their relatives close to the river rebuild things after the disaster, and the other way round in cases of drought in inland areas. This is a different form of risk transfer which worked well, but societies are changing and today monetary risk transfer is more and more important.

Scott Knowles: That’s an important case to look at, and just going back to something you said earlier, unexpectedly as insurance penetration increased in the US, it actually led to – what you might expect also – investigation, concerns about fairness, concerns about protection. It actually helped to build the judiciary sector as well, because it’s such a unique kind of product. It had these interesting important effects as Americans were going through a progressive move towards increasing the safety and standard of living for individuals, so I think it’s very well worth our consideration in exactly the way you’re describing.

This text is a transcribed and edited excerpt from a conversation the two authors held in February 2017.