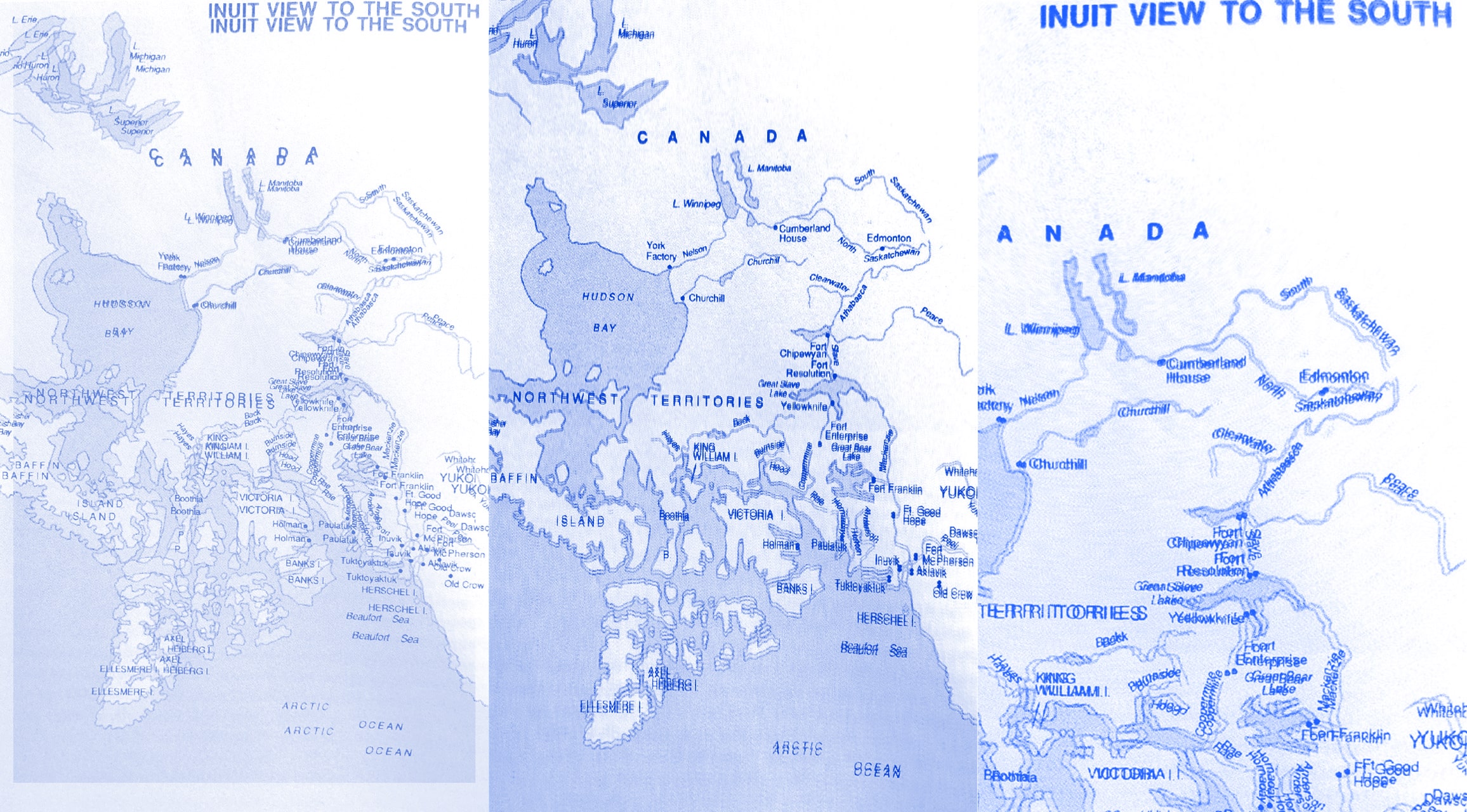

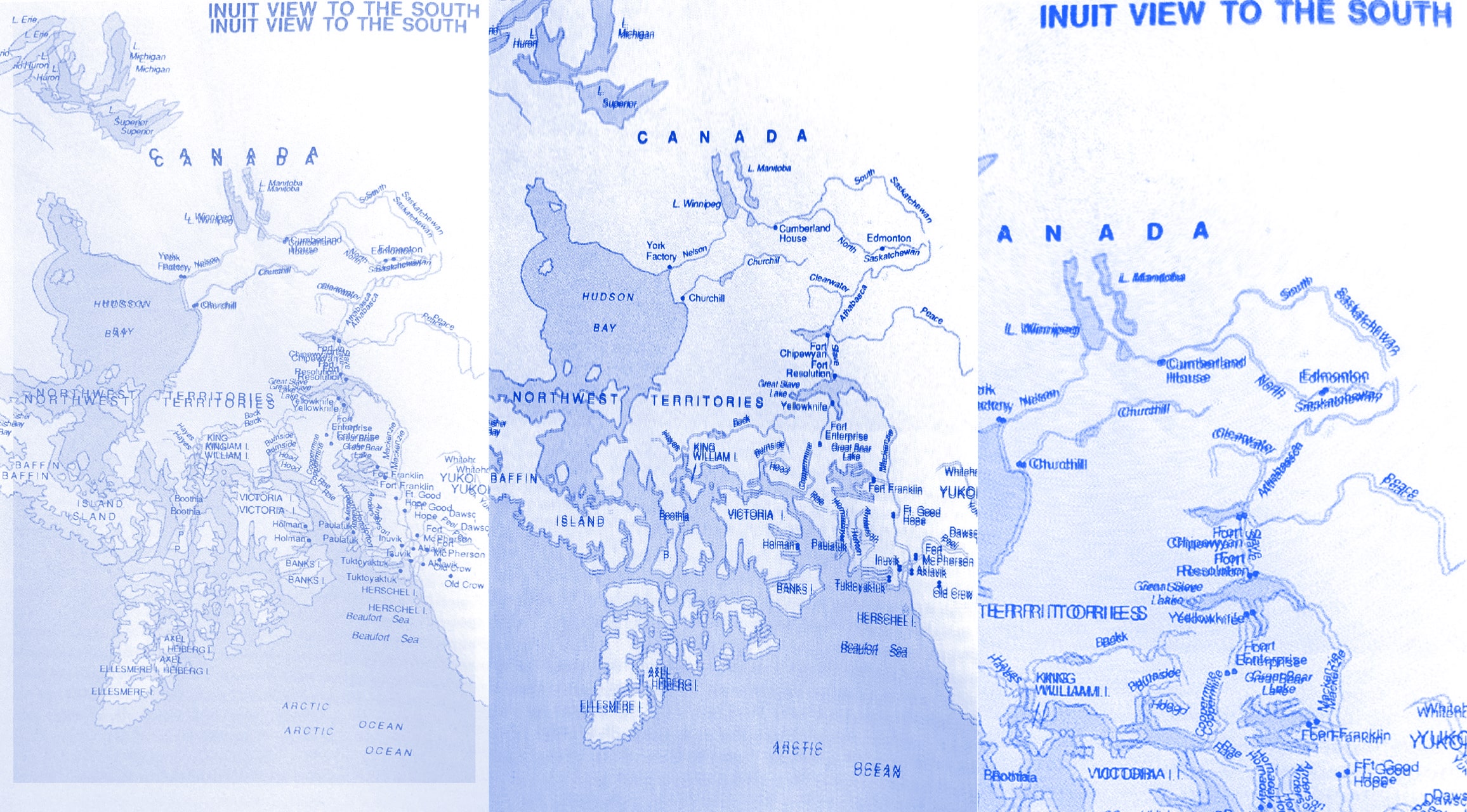

The Inuit View to the South

Original source: Rudy Wiebe, Playing Dead: A Contemplation Concerning the Arctic (1989), 333.

Sitting On Top of the World: Meridional Media, Arctic Condescension, and Northern Techniques

Based on experiences, stories, and representations of circumpolar regions, what follows examines (dis)orienting ways of technical knowing that align longitudinally. Jamie Allen's writings map the relations, tensions, and collusions between material and knowledge infrastructures and actual and modelled ecologies, and Merle Ibach prepares images to accompany these.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

June 20, 2018

It is my birthday, June 20, and I have just walked out onto the north end of Storgata Street, in the settlement that the Northern Sami people call Romsa. Others call it Tromsø, Norway. I am out front of a bar called the Verdensteatret, also known by locals as the Kino or Kinematograf. It’s a seasonable and crisp 8°C and there are clear skies above the third-largest urban area in the Arctic Circle. Looking southward, the street is flooded with an extremely elongated shadow—my own silhouette—that seems to spread all the way to the other end of this unswerving section of Tromsø’s kilometer-long high street. Somewhere near the southern end of Storgata, a group of young tourists, or maybe students, come out of another establishment, and my embarrassingly long human shadow darts over their group as I shuffle around aimlessly. A brief test of solar object permanence, a timid game of peekaboo with an occluded star. My torso intermittently creates a flickering eclipse, amplified by a cosmic ratio: the distance between the sun and I as a somewhat greater distance than the span of Storgata Street.

During the summer months in Tromsø, the sun traces out a sinusoidal band that flirts with, but never dips below, the horizon. On June 20, 2018, its oscillation apexes and bottoms out at precisely forty-five minutes after twelve noon and twelve midnight, respectively. It is late into the evening when this sun grazes an asymptote skyline, positioning its rays parallel with the straightaway pedestrian street. People become gnomons (the stick part of a sundial“The world represents itself, is reflected in the face of the sundial and we take part in this event no more and no less than the post, for standing upright, we also cast shadows, or, as seated scribes, stylus in hand, we too leave lines,” writes Michel Serres of the shaft or pin of a sundial, as “that which understands, decides, judges, interprets, or distinguishes, the rule which makes knowledge possible.” Michel Serres, “Gnomon: The Beginnings of Geometry in Greece,” in A History of Scientific Thought, ed. Michael Serres (Oxford: Blackwell 1995), 79.). Bodily and planetary meridians align. It’s as if something is trying to tell us what time it is.

Views from Nowhere

“There was a very interesting photo in [the magazine] ‘North’ which showed children in Alaska, on the Kuskokwim [River], looking at a television set for the first time. And what they were seeing on the television set, were themselves, they had a closed-circuit rigged up. I suppose, you know, in Einstein’s terms, if space is curved, and we ever get our eyesight up or our missiles up or our messages up, maybe we’ll just wind up seeing the backs of our heads. I think this, this is part of the North—it’s important.”

— “The Idea of North”, Glenn Gould’s 1967 radio composition

Earth is now evidently no longer just “our” home, no longer a carrier bag for nature, but a consummate scientific object, planetary laboratory, and ongoing experiment. The classical objective distance once required of scientific endeavors is contravened with each new site and type of “Earth Observatory” from which we purport to ob-serve and study that which we are in and on. Genealogies reconstructing the planet as the recursive, dynamic control system we understand it to be today are well charted. One starts with the eighteenth-century Scottish geologist James Hutton, who propagated the idea of immense, cyclical, and fluid scales of time and movement, with evidence in the layered, undulated folds of once molten granite that are visible up here on the surface (specifically, at Gleann Teilt in the extreme north of Perthshire, Scotland, we are told). “Solid” land is the impermanent consolidation of organic and non-organic processes. Vestiges of historical beginnings and prospects of discernable ends duly dispensed with, in the nineteenth century Charles Lyell would add to his fellow Scot’s geology a systematic uniformity of process. The Earth began to exist historically, as continuous and overlapping change operations, capable of being explained through present and observable phenomena. In the twentieth century, cybernetic models layered onto the relatively sedate rhythms of geological uniformitarianism other effective spheres radiating downward and upward as (hydro-, atmo-, bio-, techno-, etc.). Second-order cybernetic models, like the Gaia hypothesisJ. E. Lovelock and L. Margulis, “Atmospheric Homeostasis by and for the Biosphere: The Gaia Hypothesism” Tellus 26, no2. 1–2 (1974): 2–10., and the promotion of homo economicus as a force of geological redesign, systematize and modulate control cycles within these “spheres” and associate Earth’s interior, surface geology, the living, and the technological.

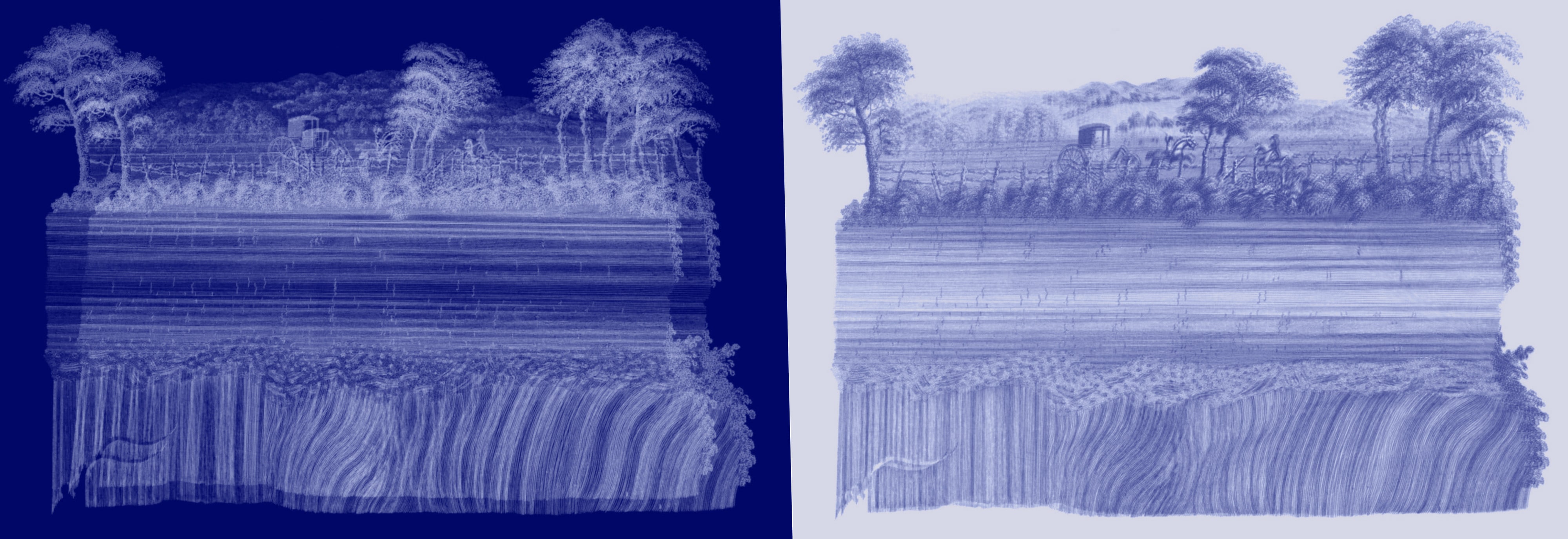

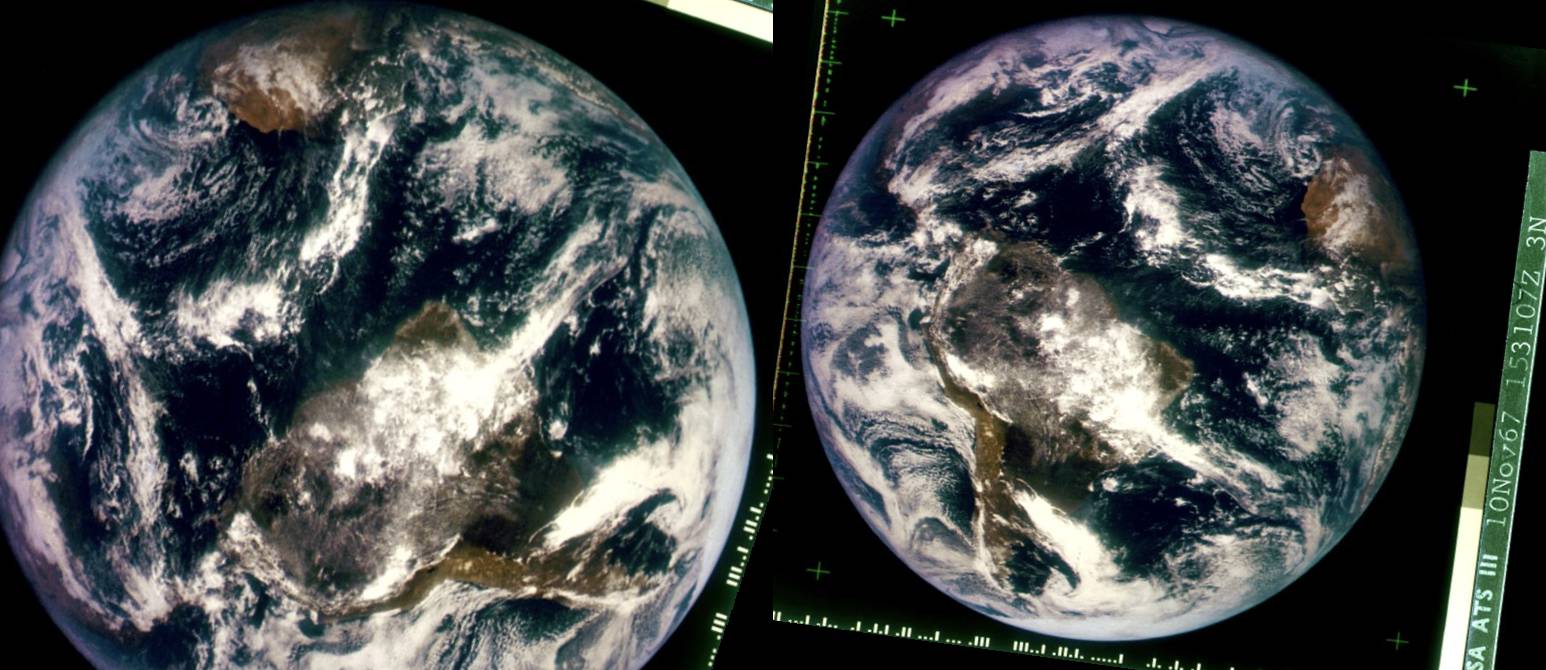

Each planetary becoming generates and is generated by particular perspectives and positions from which the Earth’s recursive objectivity is imagined. In Hutton’s and Lyell’s days, cross-sectional imaginaries propelled the importance and temporal metaphor of layers in Earth history (ge-schichte), imparting how “depth digs through time, and deep excavations down into the earth involved a kind of time travel.”Jussi Parikka, “The Geology of Media,” Atlantic, October 11, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/10/the-geology-of-media/280523. Precipitating all kinds of vertical adventures to the center of the Earth and elsewhere, the imaginary and visual expansions of technoscience move concentrically, inward and outward, very often by powers of ten, sometimes in IMAX.See Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Kees Boeke, Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps (New York: J. Day 1957); Powers of Ten, essay film, directed by Charles Eames and Ray Eames (USA: IBM, 1977); Mark Dorrian, “Adventure on the Vertical,” Cabinet, Winter 2011–12, http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/44/dorrian.php; and Cosmic Voyage, IMAX film, directed by Bayley Sillick (USA: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum 1996). Off-planet perspectives and imaginaries of self-contained, closed-system, and organismic Earths followed as centripetal and centrifugal geologies turn into revolutionist, spiraling, cyclical sphericity. In 1972, someone aboard the Apollo 17 mission used Hasselblad medium format and Nikon 35 mm cameras to snap a visual sample of the whole Earth in full spin (all three astronauts on the voyage “kind of jokingly take credit for” the photoAlexandra de Blas, “World Environment Day: Spaceship Earth,” Earthbeat, Radio National (Australia), originally broadcast June 5, 1999, https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/earthbeat/world-environment-day-spaceship-earth/3646302.). The Apollo 17 Blue Marble image was captured “southside down” in the weightless space between the Earth and its moon. Most reproductions and publications of the photograph show it inverted, to align with nordicentrist cartographic conventions.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

On July 1, 1867, at noon, Canada became a unified nation, with John A. Macdonald as its first (racist, misogynist) prime minister, and at that same moment participated in its inaugural international outing as a nation at the L’Exposition universelle in Paris. Exactly one hundred years later, the Arctic nation hosted its own universal exposition, Expo 67. It was held on new land created in the waters of the Saint Lawrence River, in the unceded Traditional Territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation, off the coast of Tiohtiá:ke, or "Montreal." The intervening hundred years had seen Canadians participate in two World Wars and help forge numerous international and humanitarian bodies, and Expo 67 was something of a coming out party for the still young nation. My dad tells me of the trip he and my mother made from Toronto to see the exposition the year before they were married, and how Expo 67 was a “big deal” for Canada. Canadian nationalism and internationalism still seem to be influenced by the event and this period—including Expo 67’s logos, media, and theme songs—not to mention a first go-round of Trudeau liberalism and leadership. It was a scene that rather crystallized still existent industrial-extractive, media-technological, multicultural, Indigenous, and Arctic relations, images, and imaginaries.Myra Rutherdale and Jim Miller, “‘It’s Our Country’: First Nations’ Participation in the Indian Pavilion at Expo 67,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/Revue de la Société historique du Canada 17, no. 2 (2006): 148–73.

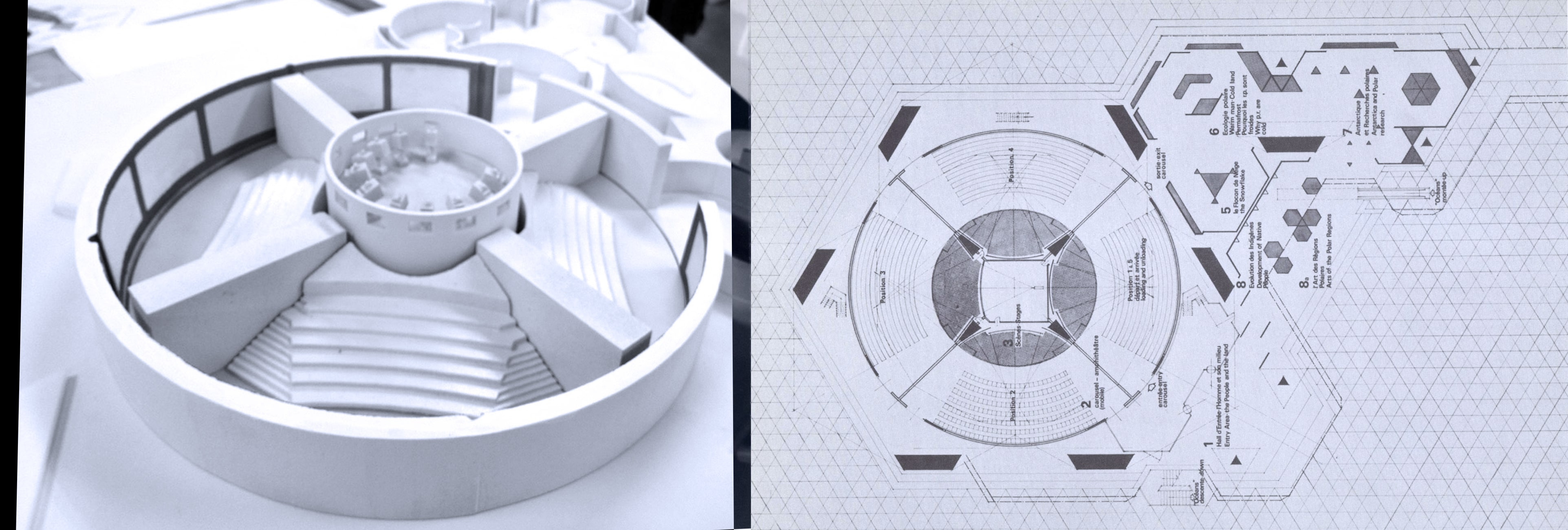

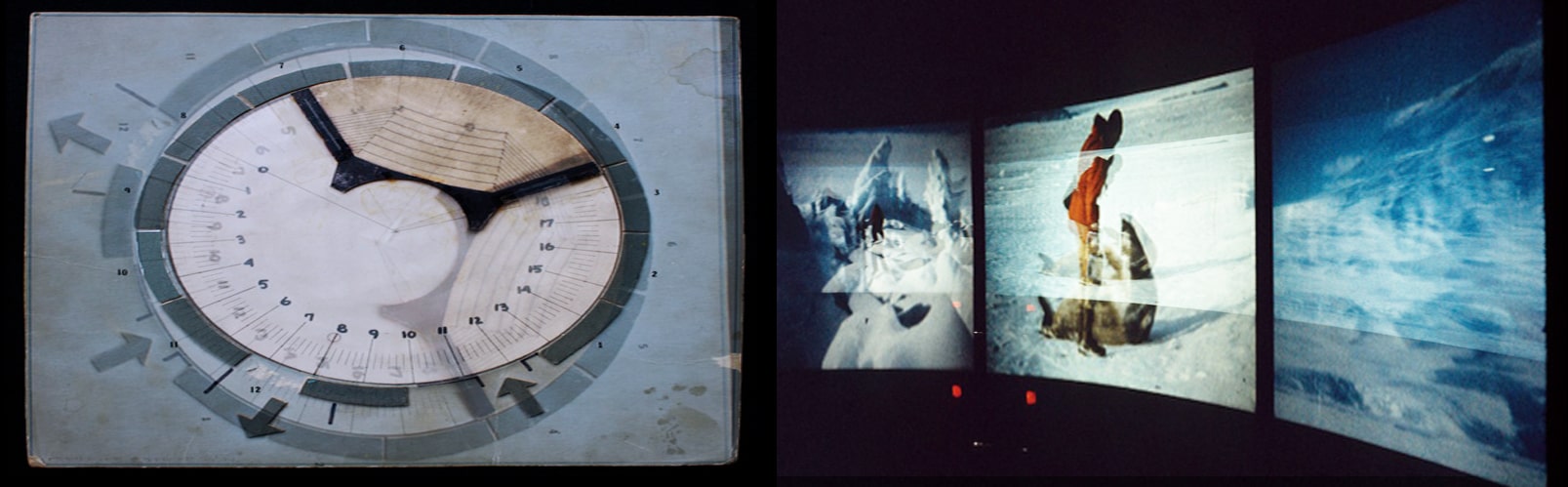

Polar Life, an immersive, multiscreen film directed by Graeme Ferguson, was the central component of the “Man and the Polar Regions” exhibit in the “Man the Explorer” pavilion at Expo 67. The film kept pace with expanded cinema developments of that period, such as Alexander Hammid and Francis Thompson’s To Be Alive!, created for the 1964 New York World’s Fair and which Ferguson cites as an influence.Monika Kin Gagnon and Janine Marchessault, eds., Reimagining Cinema: Film at Expo 67 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2014). Polar Life was besieged with production difficulties and technical presentation issues, proving so problematic for Ferguson and his colleagues in Montreal that it precipitated the birth of a company—a multimedia solutions provider now known as the IMAX Corporation. Expo 67 and Polar Life inaugurated and exemplifies a quintessentially Canadian model of technological invention and opportunism. As if trying to actualize Marshall McLuhan’s most famous insight (“the medium is the message”Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1954; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994).) while remaining true to Canada’s “founding” through colonial extraction, Canadian media industries continue to mainly provide the substrates and landscapes, systems and infrastructures of media making, technics, and backdrops for rendering and display (e.g., Quebec’s Matrox, the National Film Board of Canada, headquartered in Montreal, and Toronto as a generic stand-in for American cities in the movies).

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Produced as eleven looped films with a single soundtrack, Polar Life was experienced as eighteen minutes of immersive, pan-polar political aesthetics. The central figure is a bird, a darting and swooping Arctic tern, allowing for sequences of Kubrickesque flyover landscapes, interspersed with narration and lively, ebullient scenes of Arctic-dwelling people, communities, and a festival, as well as the serene indulgence of the Northern Lights. Most important to the evocation of meridian perspective, and among the novelties that serve as experimental precursors to expanded cinema and the immersiveness of IMAX, was that the film was presented in a “carousel theater.” The entire audience sat on a giant turntable, continuously rotating past eleven fixed projection screens. The perspective was pan-Arctic, an immersive and integrative, contiguous and sweeping portrayal from the top of the world, in the round. The experience inferred, and given to Expo 67 visitors, is the comfortable ensconcement of spectators in a kind of top-down global observatory, a (con)descending point of view that provides rotational surveys of the planet. Any collective responsibilities “we” might feel for Spaceship Earth are oriented meridionally, and the Arctic is recast as a vast protectorate from which signals and warnings from the past and the future seem to perennially emerge.

Zoe Todd, writing on the erasures that this kind of circumpolar globalism can enact on Arctic Indigenous Peoples and their laws and philosophies, notes how “Greenpeace reminds us daily, after all, that the Arctic is a commons in need of saving from climate change,” just as “climate change and the Arctic are inextricably bound in the public consciousness.”Zoe Todd, “An Indigenous Feminist's Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word for Colonialism,” Journal of Historical Sociology 29, no. 1 (2016): 6 To avoid adding the insults of knowledge extraction and epistemic colonialismCosmologist, science writer, and equality activist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein’s “intellectual colonialism” encapsulates how “pure” science enhances imperialist and corporate projects; see Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, “Intersectionality as a Blueprint for Postcolonial Scientific Community Building,” Medium, January 24, 2016, https://medium.com/@chanda/intersectionality-as-a-blueprint-for-postcolonial-scientific-community-building-7e795d09225a. Boaventura de Sousa Santos develops “epistemicide” as the “destruction of an immense variety of ways of knowing” caused by Eurocentric modern sciences of the North that colonized and extracted from the South; see Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). to the deep injuries of material extraction and territorial colonialism that have all but expunged ways of living for Sami, Yupik, Eskimo, and Inuit Peoples, Todd calls for heightened specificity, gratitude, and respect for the Aboriginal worldviews—worldviews that are in part precipitative of current European, settler, academic and artistic fascinations with relational and nonhuman “epistemologies”.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Sitting on top of the world, together as in Polar Life, the white, preserved, frozen North is a place where you can see non-white things coming from a long way off. It is worth noting to which corners of the globe the Western mind wanders when imagining scientific knowledge, solutions, and salvation regarding planetary and climatic change. The thermometer of the Earth seems firmly planted in an imaginary piece of ice, a reassuring “far away,” both in space and time, that reinstalls the objectivity we wish an Earth observatory to have. Northern ecologies are very sensitive, and it is true that some are relatively less marked by anthropogenic change than most southern territories, making them more fruitful places to observe and study variation.“The legacy and reach of anthropogenic influence is most clearly evidenced by its impact on the most remote and inaccessible habitats on Earth.” A. J. Jamieson, T. Malkocs, S. B. Piertney, T. Fujii, and Z. Zhang, “Bioaccumulation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Deepest Ocean Fauna,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 1, no. 3 (2017): 51. However, knowledge disparities and infrastructure lopsidedness demonstrate shamefully divisive attitudes and practices that are punitive and still operative. These disparities include well-known things like the “map bias” that causes differential appreciation of northern territoriesBrian P. Meier, Arlen C. Moller, Julie J. Chen, and Miles Riemer-Peltz Meier, “Spatial Metaphor and Real Estate: North–South Location Biases Housing Preference,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 2, no. 5 (March 23, 2011): 547–53. and how the Brandt Line has replaced the Iron Curtain as the spatial fulcrum of binary global rift.The Brandt Line is a visual depiction of the North-South divide based GDP per capita proposed by proposed by German statesman Willy Brandt in the 1980’s. Brandt Commission, North-South: A Programme for Survival. The Report of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues under the Chairmanship of Willy Brandt (London: Pan, 1980). The Arctic is the site of a “new Cold War unfolding at the top of the world.”Neil Shea, “Scenes from the New Cold War Unfolding at the Top of the World,” National Geographic, October 25, 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/10/new-cold-war-brews-as-arctic-ice-melts. These disparities also evince straight-up systemic north-south racism, as fallacious and repugnant as it is contemporary; witness German populism’s projections of south-Mediterranean cultures as Europe negotiates its “union”“Fass mich nicht an, du dreckiger Grieche” (“Don’t touch me, you filthy Greek”) was shouted after Peter Ramsauer, German transportation minister, experienced unintentional physical contact during an official visit to Athens (Yiannis Mylonas, “Race and Class in German Media Representations of the ‘Greek Crisis,’” in The Media and Austerity: Comparative Perspectives, ed. Laura Basu, Steve Schifferes, and Sophie Knowles (London: Routledge, 2018)). The Swiss People’s Party, as just one other example, “does not shrink from using racist language and imagery in its propaganda” and is currently among the most powerful political movements in Switzerland (Liz Fekete, Europe's Fault Lines: Racism and the Rise of the Right (London; New York: Verso Books, 2018), 22). or nordicist exceptionalism in US international policy manipulations in South America.See Rubin Francis Weston, Racism in US Imperialism: The Influence of Racial Assumptions on American Foreign Policy, 1893–1946 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1972); and David Slater, “Geopolitical Imaginations across the North-South Divide: Issues of Difference, Development and Power,” Political Geography 16, no .8 (1997): 631–53. Or, more simply, do you think smart people are more likely to be from New York or Florida?Dante A. Puzzo, “Racism and the Western Tradition,” Journal of the History of Ideas 25, no .4 (1964): 579–86. English sisters Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill, both writers, pulled through harsh Ontario winters in the 1830s while concocting missives of struggle and survival for readers back in the Old World. Their settler natural histories confirmed and redeployed existing myths of white, European, nordic supremacy:

When we consider the progress of the Northern races of mankind, it cannot be denied, that while the struggles of the hardy races of the North with their severe climate, and their forests, have gradually endowed them with an unconquerable energy of character, which has enabled them to become the masters of the world; the inhabitants of more favoured climates, where the earth almost spontaneously yields all the necessaries of life, have remained comparatively feeble and inactive, or have sunk into sloth and luxury.Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush; or, Life in Canada (1857; Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988), 519.

The Arctic is a progressively less frozen global frontier that remains remote, inaccessible, and seemingly endless, tied to myths of colonial expansion, protectionism, and infinite potential. The North, an objective vantage point for planetary surveillance, also still aligns with Cold War constructions of Arctic Canada as an evacuated “white belt,” where tripwires could be laid against the encroachment of communism. The Distant Early Warning Line was one such joint US-Canada installation that eventually required a $575 million environmental cleanup to stabilize contaminated soils and landfills at forty-two tactical and reconnaissance installations across Arctic Canada. The drive of modern Arctic nations toward the realization of the projected infinite potentials of the North continues a historical becoming-infrastructural of the region and its people.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

June 17, 2018

Like Expo 67, and made public in the same year, “The Idea of North” is the kind of radio program that forms part of the cultural wallpaper of my home nation of Canada. I heard it more than a few times on CBC Radio while growing up. It is a mark of the production of Canadianness itself for the “cultured” white settlers of my nation. In his opening address at the start of the hour-long broadcast, pianist Glenn Gould observes, “Like all but a very few Canadians, I’ve had no real experience of the North. I’ve remained, of necessity, an outsider. And the North has remained, for me, a convenient place to dream about, spin tall tales about, and, in the end, avoid.”Glenn Gould, “The Idea of North,” part 1 of “The Solitude Trilogy,” CBC Ideas, originally broadcast December 28, 1967. Untold research projects, artworks, and media profiles since Gould’s time have obligingly attempted to compose non-objectifying understandings of the static between the imagined transmissions and grounded realities of the North and the Arctic. A very select list of such experiments could include R. Murray Schafer’s composition for snowmobile and orchestra “North/White” from 1973, the multimedia investigation of Arctic magnetospheres Little Earth by London Fieldworks in 2005, and Leslie Reid’s milky-white paintings of the atmospheres of the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard from aboard the Antigua, a triple-masted tall ship, as well as earlier work that came out of the Canadian Forces Artists Program. Acoustic Ocean, a 2018 work by Ursula Biemann, is a perspectival scientific and sonic reverie, filmed in the northern Lofoten Islands, that casts sensitive subsea life in the Arctic as a canary in the global coal mine, as a dashboard for planetary drives. In the film Manifestations (2017), directed by Leena Valkeapää, narrator and nomadic Sami reindeer herder Oula A. Valkeapää says, “It feels like life is an eternity.” The North’s calls of projected solitude and infinitude, its portentous signals, once transceived, are difficult to ignore.

Perhaps in response to these drives, calls, and signals, I arrive at Tromsø airport on June 17, 2018, with a small group of Central European researchers and artists. I look across the luggage collection area while waiting for our bags and see a set of light boxes, advertisements for Kongsberg Spacetec and Kongsberg Satellite Services (KSAT). The first placard reproduces a well-worn image of KSAT’s Svalbard satellite station, and the other, a striated, glacial ice island floating in immaculate, glassy-blue digital waters, on the surface of which the words “METEOROLOGY,” “CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING,” and “SURVEILLANCE” also float.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Techniques of North

Many people they picture the Arctic as an empty white space with polar bears, but the Arctic is a high-tech corner of the earth. At the top of the world, conditions are optimal for downloading data from polar orbits. We are building a smart and dynamic Arctic, using the opportunities that technology offers, so that we can create sustainable and innovative businesses in the north. As the ice melts we will see increased activity in the region. Better connectivity is fundamental for safer marine transportation, better search and rescue capacities, and improved oil spill preparedness. It is also essential for the monitoring of natural resources so we can harvest them responsibly.”

—Kåre R. Aas, Norwegian Ambassador to the United States, 2018K. Aas, “Arctic Frontiers Abroad Seminar on Space Technology for a Smart and Resilient Arctic” (panel discussion, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC, June 11, 2018), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/space-technology-for-smart-and-resilient-arctic.

“Not to suggest that climate is not still very, very important, and we have to address that, but maybe we need to push out more to ensure that this aspect—the role of technologies and satellites and communications in a better-connected Arctic—moves to the top of the list.”

—Lisa Ann Murkowski, US Senator (Republican) for Alaska, 2018L. Murkowski, “Arctic Frontiers Abroad Seminar on Space Technology for a Smart and Resilient Arctic.”

Louis-Edmond Hamelin, the Quebecois elder statesman of northern geographies, has worked for half a century on fertile concepts such as “winterity” and “nordicity” in order to juxtapose real, extreme environments of high-latitude regions with the rich and complex ways they are perceived, imagined, depicted, and talked about. Hamelin even developed a “nordicity” scale, used by governments to allocate infrastructure and environmental resources. He named it the VAPO, or “valeur polaires.” The VAPO is a composite and somewhat subjective measure that tracks ten different aspects—things like “annual cold,” “types of ice,” as well as “accessibility by means other than air” and “degree of economic activity”— rating each on a scale between 0 and 100. The total score, out of a thousand, must be over 200 for a place to be considered “in the North.” The North Pole itself has a theoretical value of 1000, as VAPO as possible.

If boreal regions are imagined as a source of redemptive energies and infinite resources, then one way in which people use, abuse, or at least imagine northern territories is through the expectation of transformative, ascetic atonement in a world of hyper-attachment. If life gets tough in the south, if things get too harsh in the city, you can always head north, live on the cheap, and maybe even land a job with “isolation pay.” Edward Said wrote of an impossible “withdrawal from the world,” referring to Glenn Gould’s retreat away from the cultural life of southern Canada toward an imaginary North that he hoped would answer the nordic call of solitude.Edward Said, The World, the Text, and the Critic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983). Long drives in subarctic Northern Ontario in his beloved Lincoln Continental were part of the “technological self” that Gould cultivated.Edward Jones-Imhotep, “Malleability and Machines: Glenn Gould and the Technological Self,” Technology and Culture 57, no. 2 (2016): 287–321. This ascetic sensitivity to the cleansing promise of the North is most notoriously elaborated in the “Solitude Trilogy” — of which “The Idea of North” was one part — the first in a triptych of contrapuntal edits of ethnographic interviews of Northern Canadians, composed conversations overheard on an imaginary train ride along the western coast of Hudson Bay.

The numerous field stations I have visited in Canada, Finland, Sweden, and Norway are seasonally populated by researchers who spend their teaching and semester time in southern cities—Helsinki, Oslo—but find their way up to Kilpisjärvi, Ramfjordmoen, and elsewhere when there is enough light to do their fieldwork. Part of the draw of ecological fieldwork is no doubt the promise of an alchemical refinement of self in solitary and remote interaction with, and embeddedness in, one's subject matter.George E. Marcus, “Contemporary Fieldwork Aesthetics in Art and Anthropology: Experiments in Collaboration and Intervention,” Visual Anthropology 23, no. 4 (2010): 263–77. The clean, pristine elements, environments, and horizons of the North promise salvation through simplicity, and the ability to thrive in extreme cold and in the absence of creature comforts, and other creatures, reconfirms a certain sanctity of self.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The azure, blue crispness of northern skies is also technological blue: “If you’re looking to establish a futuristic interface, shades of blue are an easy bet.”Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel, Make It So: Interaction Design Lessons From Science Fiction (New York: Rosenfeld Media, 2012). Blue is the most popular color on the internet.Margaret Rhodes, “The Most Popular Color on the Internet Is...,” Wired, September 13, 2016, https://www.wired.com/2016/09/popular-color-internet. As Eric Snodgrass points out, there is “Tech logo blue. Facebook blue. Soothing, corporate IBM deep blue. The chirpy, social pastel of Twitter blue and the vaguely translucent gradients of iOS 7 blue. A showy blue LED…”Eric Snodgrass, “Blue – The Most Popular Color on the Internet,” A Peer-Reviewed Journal About 3, no .1 (2014): www.aprja.net/dusk-to-dawn-horizons-of-the-digitalpost-digital/?pdf=1437. Digitality, like nordicity, projects (cyber)spaces of limitless cleanliness and apocalyptic decontamination, a technoscientific and nordic future of cold labs and clean rooms lit in sapphirine hues. Climate change discourses and realities also put the High North squarely in that “place” we call “the future,” as people imagine where it is they will need to withdraw to when seas rise and tree lines, agricultural promise, and livable environments move north. There is a frozen seed archive, adorned with a modernist cerulean light sculpture, somewhere up there in Norway …

As a place that most people just don’t go, “North” is a discursive system, a mythic structure, a historic and narrative device, a cultural technique. Henry Morley, writing in Charles Dickens’ popular weekly Household Words in 1853 sets the tone: “There are no tales of risk and enterprise in which we English, men, women, and children, old and young, rich and poor, become interested so completely, as in the tales that come from the North Pole.”Henry Morley, in Household Words: A Weekly Journal, vol. 7, edited by Charles Dickens (London, 1853), http://www.djo.org.uk/household-words/volume-vii.html. For white people, particular desires emerge, and preferred elements, forms, colors, and figures recur when we depict or imagine circumpolar regions. Certain others, such as Arctic Indigenous Peoples and their ways of being, are often discarded.

Yuk Hui’s idea of a cosmotechnics is an enabling directive, a unification of cosmic orders and moral, human activities through technology, accounting for how we value technics and technical instruments.See Yuk Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (Falmouth: Urbanomic Media, 2016); and Yuk Hui, “ On Cosmotechnics: For a Renewed Relation between Technology and Nature in the Anthropocene,” Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology 21, nos. 2–3 (2017): 319–41. What parts of “nature,” and what parts of “our nature,” create the desire for us to bifurcate and then map out ecologies of which we are a part, in service of inevitable use and exploitation? If we were to open a dossier on the cosmotechnics of the Arctic, it would have to include how the navigator’s compass aligns with the poles and that cultures since time immemorial have taken advantage of the fact that the skies above the Earth seem to rotate around the North Star, or Polaris. Perhaps this coincidence is enough to explain why maps are consistently oriented with north at the top. It may explain, as well, how exploration, navigation, and mapping now compel astronomical and extraplanetary communication and exploration ever upward. Other entries in such a dossier would include the routine use of polar territories as simulation and training grounds for astronautsJack W. Stuster, Space Station Habitability Recommendations Based on a Systematic Comparative Analysis of Analogous Conditions, NASA Contractor Report 3943 (Washington, DC: NASA: 1986), https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19880015988.pdf and robonauts“Driving to Mars: In the Arctic with NASA on the Human Journey to the Red Planet” (2006) contains American poet William L. Fox’s writings on an excursion with NASA scientists to the research camp at Haughton Crater, a remarkably Mars-like environment on the world’s largest uninhabited island, nine hundred miles south of the North Pole. and the fact that among the hundreds of lawyers employed by the US State Department, there is just one person responsible for all legal matters concerning both the Arctic and outer space, said to be called the lawyer for “cold, dark, and dangerous places.”Michael Byers, panel discussion, Wilson Center Discussion on U.S.–Canada Space Cooperation, CSPAN, originally broadcast October 2, 2018, https://archive.org/details/CSPAN3_20181002_224800_Wilson_Center_Discussion_on_U.S.-Canada_Space_Cooperation_Part_2.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Arctic Innovation Space

A new start-up culture and commercial space industry is putting all kinds of things, large and small, into the ether at a lively pace. “New Space” is the umbrella term used for these developments, a kind of zeitgeist and movement that variously sees itself as “disrupting” the nationalized and politicized arenas of off-Earth communication, exploration, and exploitation. The official Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space is annually summarized by Pixalytics, a satellite and airborne data consultancy. In 2017 alone, 453 satellites were launched, which is more than 5 percent of all known objects put into space by humans. There are 4,857 satellites currently orbiting the planet, more and more of which are relatively diminutive-scale “microsatellites” that can be cheaply deployed via space stations or that can cheaply piggyback on other launch vehicles.

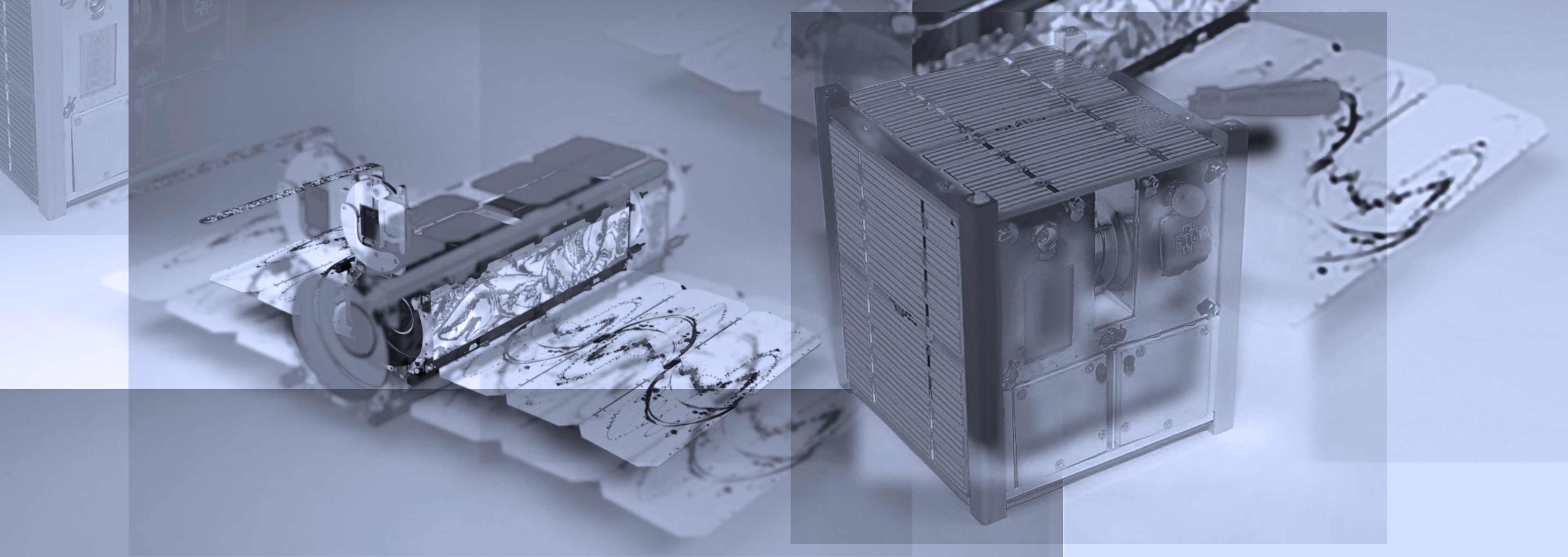

For example, the stated mission of San Francisco–based Planet Labs is “to image the entire Earth every day and make global change visible, accessible, and actionable,” a feat enabled by their in-house design and construction of mini-fridge-sized satellites they call Doves, as well as strategies like “agile aerospace,” integration with Google Cloud Platform and APIs, and service contracts with Norwegian uplink provider KSAT. The Doves’ design is based on the CubeSat concept, a 10 cm cubed satellite developed in the late 1990s at Californian universities and the subject of numerous Kickstarter campaigns. In the late 2000s, a national Norwegian student satellite program designed two CubeSats, nCube-1 and nCube-2, as part of a program also sponsored by KSAT. Neither of the two CubeSats became operational, but the program was deemed successful in “stimulat[ing] further growth of the already fast growing Norwegian space industry.”J. Antonsen and T. Houge, “The Norwegian Student Satellite Program, ANSAT,” in ESA Symposium on European Rocket and Balloon Programmes and Related Research (Bad Reichenhall, Germany, 2009). ALE Co. Ltd. is a Japanese company that in 2018 partnered with KSAT to provide “artificial on-demand meteor showers.” ALE’s CEO, Lena Okajima, says she came up with the idea while watching the Leonid meteor shower in 2001: “I knew back then that if I were to launch my own venture, it will be one that produces shooting stars on demand.Alex Martin, “The Sky Is the Canvas: Tokyo Startup Looks to Launch World’s First Artificial Meteor Shower,” Japan Times, August 29, 2018, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/08/29/business/corporate-business/sky-canvas-tokyo-startup-looks-launch-worlds-first-artificial-meteor-shower. Most New Space companies do not promise synthetic meteoritic fireworks for on-planet observers. They are mostly interested in looking back at planet Earth.

The Arctic is becoming a kind of nordic El Dorado and the North Pole an extraterrestrial antenna and trading post. On the one hand, historical and material practices of transport and extraction are activities that necessitate intensification of communication infrastructures and instrumenting of the region. On the other, epistemic extraction and cognitive colonialism are harbingers of the inevitable escalation of material and territorial variants of the same. The transport and extraction of information (“telecommunications”) serves corporate exploration and exploitation needs. Conventional Arctic petrochemical, transport, mineral, and fish companies are all assured benefits as the climate changes and decreasing ice cover opens up new drill sites, thoroughfares, easier exportation of raw ores, and northward fish and animal stock migration. To this list of Arctic value we can add great surges of data, dumps of geographical and climatological satellite payloads that are now “near real time.” Coming undersea fiber optics installations on the Arctic Ocean floor push the prospect of ever quicker data paths between Asia and Europe, valuable for high-speed markets and micro-trading transactions. Arctic ground stations and telecommunications systems are never installed to serve local end users (referred to by infrastructure groups as “anchor tenants” or “anchor customers”) but are linked to more southern centers of power, fiber optically. International climate research groups, as well as weather services like NOAA, connect to Arctic ground stations for storm monitoring and travel advisories. Clients for the data that stream through the Arctic at near real time are logistics, shipping, and petroleum companies with command centers elsewhere. Of interest are ice flow changes and openings that, for example, allow for the passage of products and equipment across the Arctic Ocean, as well as information gathering on climatic anomalies, growing ever more frequent, that might capsize a tanker or dislodge an oil rig. Earth-observation satellites using techniques like synthetic-aperture radar are essential to these newer, bigger operations in the Arctic, as they provide vision without light. The requirements of global capitalism demand twenty-four-hour, 365-day-a-year ground operations, and synthetic-aperture satellite data provide synthetic vision during long polar nights during which there is no sun under which to labor.

The twenty-first century has seen Norway arise as both petrocultural and extraplanetary infrastructure for the rest of the world, in reality and in our projective popular media. The country’s charmed planetary positioning and geology, relatively small population, compact geography, and efficient bureaucratic structures has positioned the Arctic nation as harbinger and beneficiary of new industrialization in the north. Due attention is corroborated by the recent popularity and topicality of the Norwegian Netflix hit Okkupert (Occupied), a near-future drama in which Norway self-imposes an ecologically minded oil embargo, triggering its occupation by neighboring Russia, backed by an oil-addicted European coalition—that is to say, Okkupert projects Norway’s global infrastructural becoming. Even as the energy industry—coal, oil, gas, hydroelectricity, and their transport—vastly outstrips the communications sector as a proportion of Norway’s GDP, few industries manifest the importance of Northness and nordicity to industrial exploitation like that of satellite ground services. Locating satellite ground stations above the Arctic Circle is particularly advantageous for accessing polar-orbit satellites, and these regions are typically flat and devoid of interruptive buildings and the meddling of animals, human and non-. Things up top are also rather celestially stable, as the linear velocity of a rotating sphere is zero anywhere along its spin axis (Earth’s “poles” are defined as the point where this axis meets the surface of the Earth). Arctic antennas are often seen pointed nearly horizontally, as they can also “see” a median number of non-polar orbit satellites as they clear the horizon. Other key advantages include the relative (and interrelated) meteorological and political cooperativeness and stability of Arctic nations.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

KSAT is one of very few satellite service provision companies the world over, with twenty-one licensed ground stations globally. It now also positions itself as one of Norway’s New Space players, interested in the small satellite segment. The company’s corporate lineage is a market-success story of privatized public infrastructure. Unlike Planet Labs, KSAT makes no gestures toward vertical integration through satellite hardware development but instead sells its ground station data-pipeline services to any and all comers.“KSAT has one big advantage and that’s that we’re independent of the data source. If you own one satellite, you tend to use only that satellite and the end users, for example the oil companies, really don’t care what satellites you’re using” says Rolf Skatteboe, president of Kongsberg Satellite Services. Rolf Skatteboe, “Profile | Rolf Skatteboe, President, Kongsberg Satellite Services,” interview by Warren Ferster, SpaceNews, July 16, 2012, https://spacenews.com/rolf-skatteboe-president-kongsberg-satellite-services. Their 2017 Annual Report lists among their activities the operation of a global ground station network, with key pole-to-pole coverage through sites in the Antarctic at TrollSat (72°S) and in Norway at SvalSat (78°N) and Tromsø (70°N). This enables coverage of nearly all twenty-eight passes made by polar-orbit satellites above the North and South Poles each day. SvalSat, the Svalbard Satellite Station, on the largest island of the Svalbard archipelago, is just down the road from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (78°14’16.8”N 15°26’19.5”E).

KSAT’s services include telemetry, tracking and command, oil spill detection, vessel tracking, and “multi-mission” near-real-time data provision. The terminology of this latter, at first a rather vague- and innocuous-sounding activity, divulges KSAT’s unsurprising involvement in military and defense activities and markets. Unsurprising, as KSAT’s co-subsidiary Kongsberg Defence Systems (KDS) builds missiles and missile-strike technologies, remote weapon stations, and other systems for defending and killing people. Unsurprising as well when glancing at KSAT’s Twitter ecosystem (@KSAT_Kongsberg)—a heady mix of feel-good community, entrepreneurial, research, and educational announcements appear alongside defense speculation, simultaneously “excited to support @SpaceX” and weighing in on suggestions “that a conflict on earth could bleed into space.” KDS customers include various NATO partners such as Germany and the US (this latter relationship began with the Norwegian production and exportation of “the Krag,” the Krag–Jørgensen rifle, which was adopted as the standard issue US Army rifle, used by hundreds of thousands of soldiers at the turn of the nineteenth century). The parent company of KSAT and KDS, Kongsberg Gruppen, is majority owned by the Norwegian government, and questions are arising about the use of its ground stations for military operations—particularly those at SvalSat. The 1920 Treaty of Svalbard with Russia strictly prevents Norway from using the region for military operations of any kind, but the use of data that passes through KSAT’s ground stations by US, Norwegian and NATO military interests is difficult to forestall, or deny.Kristian Åtland and Torbjørn Pedersen, “The Svalbard Archipelago in Russian Security Policy: Overcoming the Legacy of Fear—Or Reproducing It?,” European Security 17, nos. 2–3 (2008): 227–51.

KSAT’s particular corporate narrative is self-styled as a history of their Tromsø site, where in 1967 the Royal Norwegian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research set up Noway’s first telemetry station. The station’s birth as a satellite ground station is precisely timed. A nine-minute flyover of Europe’s first satellite, the European Space Research Organisation’s ESRO 2B, began when Tromsø confirmed acquisition of signal (AOS) at 03:31:15 AM, May 17, 1968. The 1980s and ’90s were darker and developmental years, respectively, but the 2000s saw the establishment of KSAT as a commercial operator. KSAT is now the world’s largest supplier of services for the control of and data acquisition from polar-orbit satellites. It is still headquartered in Tromsø, on the grounds of the original and still-active receiving station, where the complete KSAT network is operated as one single interconnected network out of the Tromsø Network Operations Centre.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

June 18, 2018

In two days, it will be my birthday. Myself and a small group are walking the three-hundred-meter path between the parking lot of Tromsø’s Charlottenlund Recreational Park over to the site of KSAT's global headquarters and satellite ground station. Norway entered the space age on May 17, 1968, so this year is the ground station’s fiftieth birthday. We are a month late to visit on the precise anniversary, but the skies and general conditions would have been quite similar. KSAT will in any case not officially celebrate its jubilee until September 28, with an exclusive outdoor concert on these grounds for one hundred lucky guests. We have just had lunch. Locals in Tromsø are rumored to harvest (steal) and eat seagull eggs, but we see no sign of this practice, nor does it ever come up in conversation with anyone while we are there.

As we approach the KSAT grounds, one of the midsized white parabolic antennas is hastily repositioning itself to catch something on an opposing horizon. Almost missing this unpredictable event, we all shuffle for our mobile phones and cameras, capturing the drama only partially. This sudden, smooth robotic movement distracts everyone from how unexpectedly accessible the grounds are. No perimeter fences, alarm systems, or security guards impede our access to the larger dishes, domes, and a new, strangely half-unboxed bowl, three meters in diameter, just sitting in the parking lot. The whole scene looks a bit like a boneyard, or a chop shop for stolen space telecoms gear. The collection of active, retired, and to-be-installed materials look as if they have been ploddingly cannibalizing one another. Unprotected and unsurveilled, the whole ground station area seems sort of unremarkable, for all the information fluxes taking place—the state secrets, climate change patterns, oil tanker coordinates, streaming through our own fleshy, boney electromagnetic signatures.

I try and get closer to a spherical dome structure that seems to be out of service. A bird—not an Arctic tern, but one of the very, very large seagulls that dominate the rooftops and command attention in the public squares of Tromsø—squawks angrily at me from the top of an adjoining tower. I continue my move toward the white globe and the gull aggressively dives at me, darting and swooping over my head, strafing me with an ample discharge of bird shit. The payload squarely connects with the top of my increasingly hairless head. I’m stunned, both by the fouling I have received and by the truly admirable aim of this massive seabird. I beat my retreat back to the human group, realizing as I back away that I had been encroaching on a small nest of seagull eggs in the tall grasses around the satellite dome. The Arctic bird had been safeguarding its unborn kin. Our initial impression that this ground station had been left unsurveilled and unprotected was entirely incorrect.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The title “Sitting on Top of the World” referes to a country blues song and standard of traditional American music, written by Walter Vinson and Lonnie Chatmon and first recorded in 1930.

Acknowledgements

Thinking and making are impelled by always and continuously collaborative study, for which I am grateful and have been fortunately blessed of late. Specific acknowledgment sufficient to the collaborative warmth and generosity I have been extended, and the gratitude I feel for this, may be impossible or superfluous, but here’s a start: Research related to this article first emerged through a 2016 Traill Fellowship at Trent University in Peterborough, Canada (a collaboration with Kelly Egan, Assistant Professor of Visual and Media Studies there) and via a “Northern Atmospheres” event in 2017 supported by the Speculative Life Cluster at Concordia University, Montreal (graciously hosted by Orit Halpern with Treva Pullman, Antonia Hernández, Whitefeather Hunter, Tricia Toso, Cécile Martin, Annabelle Demy, Greg Bedell, Axel Jadotte, Jackson Ainsworth, and Valérie Picard). Many thanks to Martin Howse, Merle Ibach, Kristin Tårnes, Alfred Benedict Marasigan, Maximilian Vinzenz Schob, Rinalda Faraian, and the good people of Kurant Visningsrom for traipsing through and thinking in Tromsø with us, and for celebrating my birthday with me under the midnight sun. Gratitude to the Finnish Bioart Society and the staff of the University of Helsinki Kilpisjärvi Biological Station, especially Heidi J. Blom, who kindly organized arrangements for Shift Register project researchers while we were in the Sápmi region in 2018. Thanks to David Clark for reintroducing me to the Polar Life dossier, to Garance Malivel for sending me a picture of the cover of Le Un from her breakfast table in Paris, and to Merle, again, for patiently and iteratively making the images that accompany this essay.