5. Deserts. The Geopolitics of Geology

Monopolies of raw materials are as much political and historical as they are based on “natural” resources. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the growing dependency of national food supplies on fertilizer has turned phosphorus into a critical resource within geopolitical conflicts. Lino Camprubí tells the (post-)colonial and geopolitical history of the Western Sahara—the last African colony that still exists to this day—and gives historic insight into why Morocco holds approximately seventy-five percent of the world’s usable phosphate. Timothy Johnson’s article highlights how World War I exposed the vulnerability of a fertilizer-based agricultural system, but also helped install mineral-fueled agriculture.

The Last African Colony and Moroccan Phosphate Mining

Western Sahara rarely makes it into the news. In 2011 Saharawi riots at the Tindouf refugee camp in Algeria led human rights organizations to once again raise up the issue in the UN. When in 1975 Morocco seized Western Sahara from Spain, its former colonial ruler, most of the native nomadic population was expelled and has been confined in that southwestern corner of Algeria for generations. While about two hundred thousand Moroccan citizens have settled in the territory since then, more than one hundred thousand Saharawi are in exile.

As it had done since its creation in 1991, in 2011 the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINRUSO) attempted to draft a resolution condemning the repression and urging for the celebration of the Referendum of self-determination that Morocco agreed upon twenty-five years ago. As usual, a number of countries blocked any attempt in that direction and avoided any talk of sanctions. The ambiguity between international law and the de facto situation is visible in how different maps, even within the Google emporium, depict the border alternatively with a continues or a dotted line. The UN recognizes Western Sahara as the last African colony, but most of the countries that constitute the UN are happy keeping it that way. Phosphate is the reason why.

According to most estimates, Morocco holds no less than seventy-five percent of the world’s usable phosphate. The enormity of the figure becomes alarming when we imaginarily apply it to other key resources, such as oil or water. If Saudi Arabia held seventy-five percent of the world oil we would have probably moved on to alternative fuels long ago! As the Phosphorus Apparatus dossier makes clear, phosphate is not any less vital than oil for today’s world population. As such, Morocco’s absolute preponderance poses enormous geopolitical challenges of which the anomaly of Western Sahara is a tragic symptom.

This article approaches the geopolitics of Moroccan phosphate mining historically. By looking at Morocco’s seizure of Western Saharan mines, it argues that monopolies of raw materials are as much political as they are natural. In this case, geopolitics and violence were at the roots of each of the three stages of fertilizer production: finding rich veins, extracting and moving phosphate rock, and manufacturing it into sellable enrichers.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Finding and counting – the geopolitics of geophysics

The two world wars marked the beginning of the end of the colonial era, with the definitive decease of empires such as the Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian, the Japanese, the Italian and the German and the severe weakening of others, particularly the British and the French. But this was far from an abrupt end, and French colonial rule would still configure North African political economy for years to come. Phosphate production functioned under this scheme, with the largest producers of raw phosphate sending the rock for manufacturing in France. The next section will examine the decomposition of this colonial division of labor. For now, I want to stress that it granted the French a virtual monopoly over the production of fertilizers in Europe.

This was bad news for France’s political rivals, as was the case with the dictatorial regime established by General Franco after the Spanish Civil War. With World War II over, France refused to sell phosphoric acid to a state that had been friendly towards the Axis. Spanish officials turned to Spain’s own colonies, in particular to Western Sahara. Hoping to find there the resources that lack of currency and political isolation prevented Spaniards to buy elsewhere, the Colonial Administration funded more than twenty geological expeditions to Western Sahara from 1941 to 1955.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

While working on his dissertation as part of one of those expeditions, geologist Manuel Alía Medina found phosphate-bearing minerals that reminded him of the rich Algerian rocks. After a meeting with Franco in 1947, it was decided to launch a state company that would prospect and eventually mine and sell Western Saharan phosphates.

At the time, geologists thought that phosphate deposits resulted from marine sediments left in land depressions during flood periods. This (wrong) assumption led prospectors towards the coast, and after years of disappointments the campaign was cancelled in 1957.

However, two other minerals offered more promising prospects: uranium and oil. Efforts to obtain them incorporated geophysics to geology, with the production of detailed geological maps that included data on radiation and electrical loggings. Importantly, this was the result of a transnational effort, because in 1958 the Colonial Administration invited over twenty companies from across the world to look for oil in the region. They too were disappointed and soon abandoned the area, living behind not only the end of the nomadic life in places like Aaiun, the new capital, but also a wealth of knowledge, tools and apparatuses.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

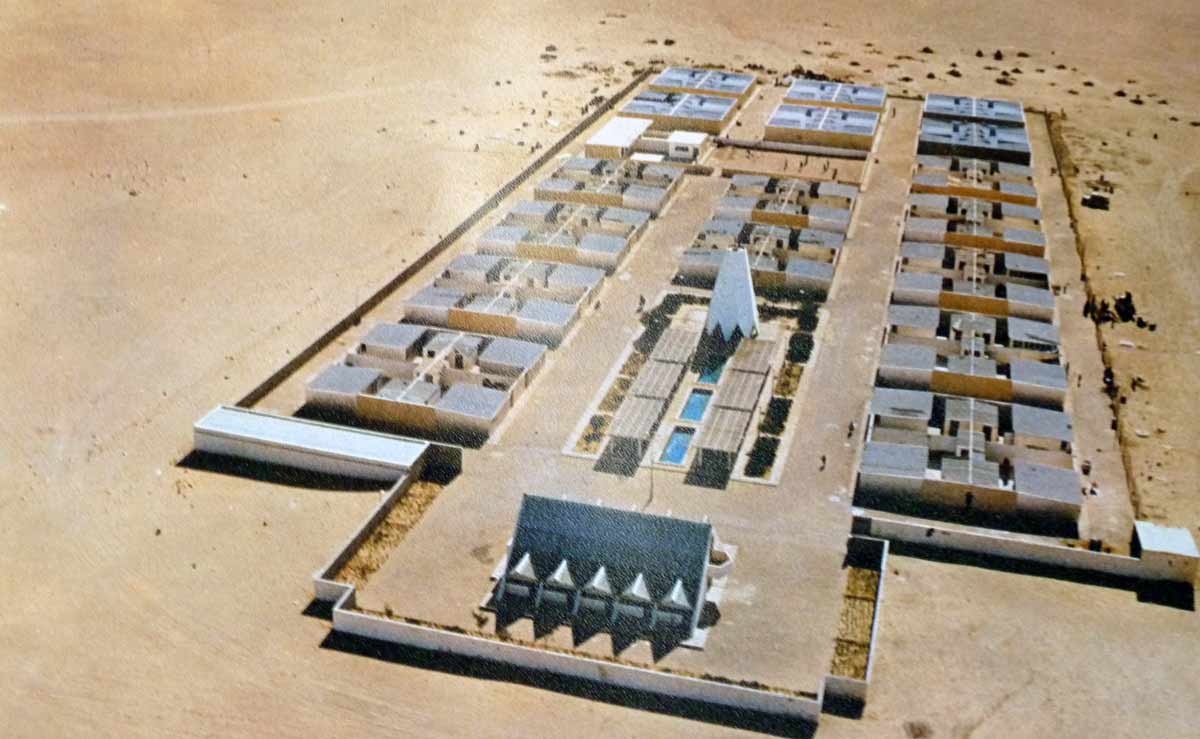

In 1962, after ruling out the possibility for profitably extracting uranium and oil, the Spanish government decided to resume the quest for phosphates with the creation of a new state company, ENMINSA. Spain had slowly been integrated into the Western Block defined by Cold War geopolitics, and France now shipped thousands of tons of fertilizers to foster the country’s rich agriculture. But the recent decolonization of Morocco, Algeria and Mauritania put increasing pressure on the Spanish government to conduct a self-determination referendum in the Western Sahara. Economic development was seen as the only possibility for keeping future voters loyal.

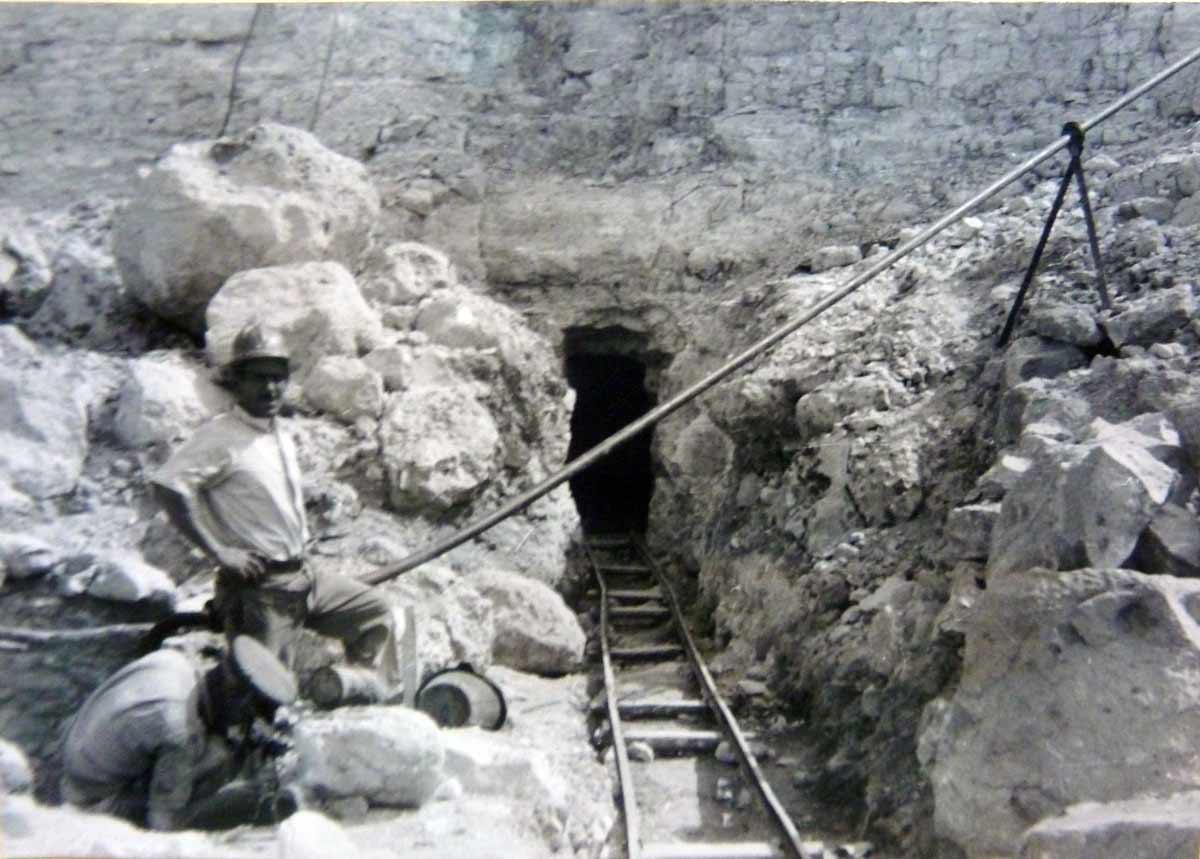

New knowledge of phosphate genesis was also reassuring. Most theories pointed toward explanations of sedimentary phosphate that combined deep marine concentrations in cold conditions with their rise by convection toward shallow coastal waters during prolonged geological periods. And the new geological maps of the area showed an ancient Paleozoic coast moving Eastward. Pairing with one of the companies which had prospected for oil in the area with the help of radioactive and electric lodgers, the Institute Français du Petrole (IFP), ENMINSA technicians followed two layers of dark flint along this ancient coast. They corresponded to those where Alía had first found phosphate twenty years earlier. In June 1963 they dig a well in the Bu-Craa region and struck on a superficial vein of surprisingly high quality.

After further prospects and complicated statistical calculations, ENMINSA reported to have found one of the richest deposits in the world, with 1,600 million tons of phosphates of sixty-eight percent average quality with veins of eighty percent purity, well above that of most mines. With that, a new geopolitical game started.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Extracting and moving – postcolonial markets

The Bucraa discovery came at a time of rapid expansion of the phosphate world market. An oil-fueled Golden Age of capitalism, a Cold War-fueled Green Revolution and the expansion of economies like the Soviet, the Chinese and the Brazilian, boosted demand for fertilizers. The Spanish government saw a unique opportunity to get a share of the wealth. This posed challenges and opportunities to government officials and CEOs from the various countries involved. Decolonization opened the way to various competing possibilities to reorganize the phosphate economy and Bucraa was the place to start.

Morocco had gained independence from France in 1956 and Algeria followed in 1962. French officials complained that the phosphate market was “ruled by anarchy”, by which they meant that they had lost its control. The division of labor between North African producers or raw phosphate and European manufacturers of fertilizers continued to be in place, but now mining nations could bargain to see which buyer offered the best deal. In particular, Morocco still sold its phosphate to France, but it did so in its own terms and was opened to speak to other manufacturers. For instance, it closed a deal with the American company Occidental Petroleum to install a refining plant in Moroccan soil, which would allow Morocco to jump over French producers.

In this context, the Bucraa discovery was perceived by the French as an opportunity to reduce Morocco’s weight in the industry, but one that would only be of use for French interests if the French officials could be in charge of some kind of new international arrangement that did not convince anyone else. For Morocco, the new mine meant an unacceptable competitor just to the south, except if it could somehow get hold of its reserves. The Monarchy launched a campaign to establish Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, what was called Grand Morocco. It also failed to convince other countries, leading to a short war between Algeria and Morocco. For US companies, Bucraa was an opportunity to enter the European market. Phosphate rock was heavy and thus subject to regional “natural markets.” Bucraa was for them a unique occasion to manufacture a truly global market.

Lastly, Spain needed to play its cards carefully. The UN had recently listed Western Sahara as a territory awaiting self-determination. Spain thus became an administrative power in charge of conducting a referendum. The government’s strategy was to buy time until phosphates could be solved and some of the revenue reinvested to ensure a loyal native population. ENMINSA officials were charged with finding a partner to enter the global market and advised that: “the issue of independence will soon be pressing... The future of the territory depends to a great extent on what you will be able to achieve.”

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Intense negotiations followed from 1965 to the early 1970s. have discussed them with greater detail in Resource Geopolitics (Technology and Culture). Here, it suffices to say that political economy, sovereignty, war, technologies of extraction and transportation, and estimates of world reserves were all discussed with equal boldness. Just when ENMINSA and the Florida-based International Mineral and Chemicals (IMC) were about to close a deal, Morocco lowered prices for its exports, which made IMC reconsider its offer. Extended negotiations meant the delay of the construction of the installations, and thus of production, which undermined the Spanish strategy. ENMINSA chief executive considered this a form of sabotage useful to keep prices up.

Sabotage and artificial scarcity became key in the years to come.

Selling and manufacturing – Sabotage and artificial scarcity.

By threatening with a price war and by increasing diplomatic and military pressure over the Western Sahara, Morocco made it clear that it would not accept competition from Bucraa phosphate. The president of the Office Chérifien des Phosphates, the national company in charge of mining and selling the rock, explained to diplomats in Spain and the US that “many in Morocco consider phosphate to be our oil. Undoubtedly, this connects phosphate to the issue of Western Sahara.” In view of this determination and of Moroccan leverage over the world phosphate markets, Spanish officials decided to negotiate.

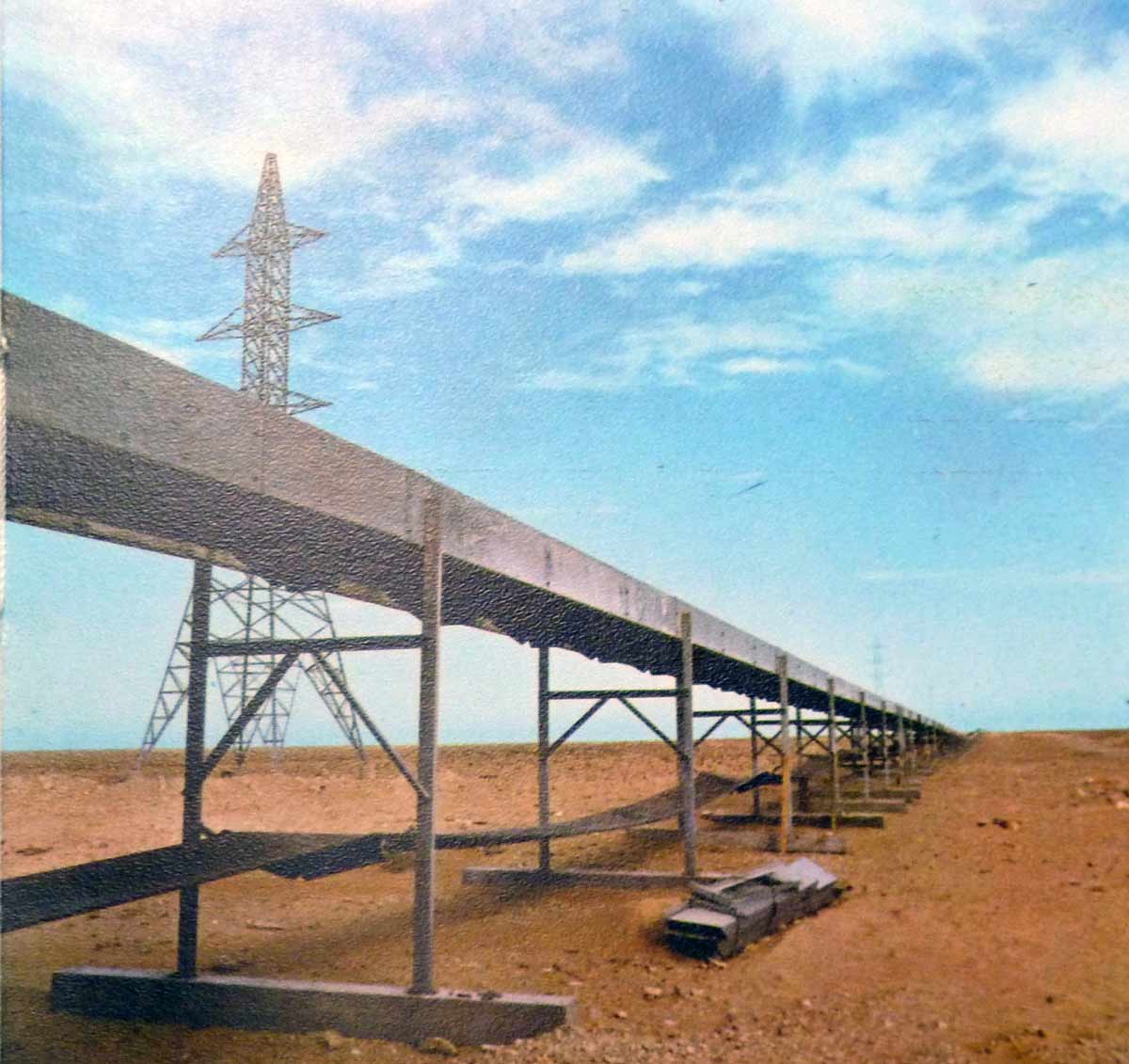

In 1972 the two countries reached a secret agreement to avoid competing for the same markets and to fix minimum prices. This allowed Spain to sell its first shipment to Japan later in the year. Phosphates extracted at Bu-Craa travelled one hundred kilometers through a conveyor belt until a new port built in El Aiun, where it was charged into containers and loaded into cargo ships. The conveyor belt thus became a mandatory point of passage for the political economy of Sahara phosphate.

As Timothy Mitchell and others have argued, chokepoints allow for new political players to instantiate their claims to participation. In October 1974, the Polisario, a group funded just the year before by pro-independence Saharawi, burned down fourteen kilometers of the conveyor belt. The Polisario, many of whose members worked at the mines and other facilities geared towards extracting phosphate, was able to disrupt the movement of the rock onto the world markets. Soon after, the Spanish government announced that it would conduct the referendum in 1975.

Fearing a negative result, the Moroccan king decided to prevent such referendum. In the US, President Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger worried about Algeria’s close ties to the Soviet Union and sought to avoid instability in Morocco as well as a Soviet-friendly Western Sahara that would give the enemy a direct entry point into the Atlantic. “If he [the king] doesn’t get it [the Sahara] he is finished; we should now work to ensure he gets it.” In Spain, dictator Franco was dying and a conflict with Morocco would have brought unwanted instability. On November 14, both countries reached a convenient agreement: Morocco would have the Western Sahara and Spain would retain thirty-five percent of phosphates.

And thus did the Western Sahara become the last African colony. Its population was bombed with Napalm and expelled to Algerian camps. A twenty-five-year long war between an Algeria-supported Polisario and a US-funded Morocco continued. Phosphates were at the center of it, with the conveyor belt suffering multiple attacks and with Morocco securing the mine and the port through walls of sand and barbed wire.

While production halted for years, Morocco had long annihilated the spectrum of a southern competitor. The goal was not always to produce as much as possible, but rather to do so at the highest price imaginable. Since the truce between Morocco and the Polisario was signed in 1991, Morocco decides how much the world pays for fertilizers.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Phosphate futures – what do we do next?

In early 2016 the NASA produced some astonishing images showing how phosphorus-rich dust from the Sahara desert feeds the Amazonic rain forest after crossing the Atlantic in suspension. Pictures like this one convey ideas of connectedness and equilibrium at a global scale. The problem arises if these ideas are extrapolated to the all-too human world of production and consumption. The phosphorus apparatus is anything but smooth. Also, unlike the technical systems that we usually call apparatus, it lacks any central organization or design.

In descending into the historical details of finding, moving and selling phosphorus, we are confronted with secrecy, violence, sabotage, scarcity and exodus. At the same time, putting phosphorus at the center of developments otherwise traversed by Cold War and decolonization geopolitics, we gain new understandings of the entanglement between the deep time of fossil formation and the accelerated pace of world population and depletion. Political boundaries and discontinuities prove themselves as relevant as flows and mobility.

It is useful to bear this in mind when thinking about what to do next. Asking “what can we do to reform the phosphorus apparatus?” is already begging the question of who is the political subject of the action. Who is the “we”? In imagining phosphorus-sustainable futures, the temptation of glossing over the central problem of the political continuities and discontinuities encapsulated in this pronoun could become strong enough to risk the entire project.

For greater detail and references, the author wishes to refer readers to his "Resource Geopolitics: Cold War Technologies, Global Fertilizer, and the Fate of Western Sahara," Technology and Culture, 57, 3 (2015): 676-703.

Towards a Global Law of the Minimum: War and the Geopolitics of N-P-K Sourcing

When war rattled the world in 1914, fertilizer flows were crucial to the nutritional circuitry of the empires of the North Atlantic. In the decades since 1840 when the chemist Justus Von Liebig identified the three nutrients essential to plant growth, commercial networks spanning the globe emerged to supply farms with nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

These flows of fertilizer minerals helped nations like Germany, Britain, and the United States create highly productive crop cultures. The outbreak of the war, however, revealed that the stunning productivity of the new fertilizer regime was vulnerable to the vagaries of geopolitics. The exigencies of a global industrial conflict only multiplied these vulnerabilities, as naval blockades interrupted the regular circulation of minerals, and military demands cut into fertilizer supplies for ordnance production.

World War I was, as Timothy Mitchell has suggested, the first carbon-fueled conflict. Fossil fuels allowed the empires of the North Atlantic escalate the scale and magnitude of warfare. Yet because these same nations also depended on mineral fertilizers to produce food and fiber, war was also the first great conflict in the mineral fertilizer regime. And while the belligerent nations entered the war with a fairly clear sense of the carbon resources needed to power their war machines, the mineral basis of their nutritional demands posed complex and unprecedented logistical challenges.

The global fertilizer map was beset with asymmetries. Even if a nation was endowed with an abundant supply of one of the three main fertilizer nutrients, usually at least one or the other two came from far afield. Germany had advanced nitrogen synthesis and a virtual monopoly on potassium, but it lacked significant domestic sources of phosphorous. Britain and the United States had access to phosphates but relied heavily on Chilean nitrate and German potash. In a sense, policymakers had to reckon with the brutal calculus of Liebig’s law of the minimum on a global scale. Warring nations struggled to protect existing supply chains and to seek other, domestic resources in pursuit of nutritional autarky.

Liebig’s law provides a framework to explore how states grappled with the uncertainties of global nutrient flows in the early twentieth century. The United States provides a case study to examine how concerns about securing N-P-K supply chains influenced the actions of a rapidly expanding state. While the United States was less dependent on mineral fertilizers than Germany, for example, its struggle to achieve fertilizer sovereignty during the war shows how the experience of war elevated the law of the minimum from the rarified sphere of agricultural chemistry to the realm of geopolitics. It also reveals that these same matters of wartime urgency helped cement the centrality of industrial agriculture and to scuttle other time-tested approaches to maintaining agricultural production after the war.

Fertilizer in the United States Before World War I

For the United States, as well as European powers, the introduction of fertilizers was intimately bound up with imperial aspirations. For most of America’s history, agricultural production had been contingent upon an empire of space. Settlers practiced extensive agriculture and tapped native fertility of the soils of the continental expanse as the key source of plant nutrition. Although politicians operated under the assumption of an endless frontier to supply the growing nation with raw materials, local problems of soil exhaustion became especially acute along the Eastern Seaboard. Following the lead of northern European nations, eastern farmers became voracious consumers of Pacific guano fertilizer by the 1850s.

The market for these nitrogen and phosphorus rich materials inspired lawmakers to pass the Guano Islands Act in 1856 to provide a legal basis for Americans to claim territory for the purpose of commercial mineral extraction. The arid reefs and rookeries of the Pacific and the Caribbean became the first waypoints of America’s overseas empire.

In the late 19th century, the market for commercial fertilizers was concentrated along the market garden districts of the East and especially in the Plantation Belt of the Southeast. There, high-value staple crops cultivated on poor soils led tenant farmers to become the shock troops of input-based agriculture. Initially many agricultural scientists dismissed these cotton and tobacco farmers as “backwards” because their approach to farming spurned the practice of agricultural husbandry, which relied upon manure and crop rotations to improve yields.

Under scrutiny, however, the recourse to fertilizers was an almost unavoidable adaptation to the political economy of the South—and one that has since been reproduced in plantation regions around the world. Lacking capital, land, implements, outbuildings, and sufficient livestock, fertilizer became a lifeline for southern agriculture. White landowners, often former slaveholders, became the commercial agents of this new nutrient trade by extending credit for the fertilizer at crippling interest rates to their tenants. In the process, the annual ritual of fertilizer application quickly transformed the southern Plantation Belt into a key site in an increasingly global circulation of mineral nutrients.

Unlike Britain and Germany, before the Great War, American politicians had given relatively little thought to how war would affect fertilizer supply lines. In his 1898 speech at the British Society, Sir William Crookes famously framed the problem of nitrogen fixation as a challenge to chemists, and as a potential technological pathway to nutritional independence for Britain—a nation almost wholly dependent on grain imports from overseas. In Germany, Fritz Haber discovered an efficient approach to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that could be used to manufacture fertilizer and explosives—a breakthrough that eventually ended Germany’s reliance on Chilean nitrates. Observing these events in Europe, in 1909 the American chemist Charles Munroe urged his own government to support research for nitrogen fixation as a bulwark against a wartime embargo on Chilean nitrates, which could hamstring weapons production as well as crop yields.

Yet Munroe’s call to action did not resonate in America the way that Crookes’s speech had in Europe. On the eve of the war, the United States remained an inwardly focused nation with an economy geared towards internal markets and built upon an unshakable faith in the nation’s territorial abundance. If the law of the minimum was already beginning to shape policy and investment in Europe, the U.S. had yet to come to grips with the urgency of resource scarcity.

Prior to the fighting, economic warfare with Germany over potash prices revealed that fertilizer minerals could pose a threat to national security. America absorbed more than half of Germany’s total potash output, but when the Imperial Government passed a 1910 law setting strict price controls, American fertilizer manufacturers sought federal interventions. In an unprecedented action, Congress commissioned the Geological Survey and the Bureau of Soils to send scientists into the field to scour the country for sources of potash and nitrates and to prepare for the threat of a fertilizer embargo. Beyond the quest for mineral resources, federal scientists also conducted a series of studies that measured the cost and efficacy of urban waste streams as fertilizer resources. This research pointed to a number of promising leads, but no simple solutions. More than anything, these studies underlined that the modern food supply chain was complex system based on interdependence, making the ideal of fertilizer independence elusive.

Diplomacy, Discovery, and Denial

The start of the war immediately upended the delicate international balance of power in fertilizer production. Due to blockades and because of their importance to arms production, the cost of raw fertilizer materials spiked in the United States long before it entered the conflict in 1917. As the U.S. and other nations faced the limiting effects of nutrient embargoes, they pursued three approaches to avoiding the law of the minimum that can be categorized as diplomacy, discovery, and denial.

Diplomacy was the first path America followed with Germany, in particular, since each nation was the largest consumer of the other’s primary mineral resource. The strongest advocates of diplomacy were American fertilizer manufacturers, who pressured the Wilson administration to keep lines of communication open with Germany. Cutting ties would mean that American phosphate companies would lose their most lucrative market and that American fertilizer manufacturers stood to lose their potash supply. Two obstacles prevented this exchange. First, beyond their agricultural applications, all of the main fertilizer minerals were crucial to weapons production, which could compromise America’s neutral position at the start of the war. Second, America’s entry with the allies closed the door to any exchange with Germany completely, while it did increase cooperation with Britain.

After the failure of diplomacy, the prospect of discovering new sources of fertilizer became paramount, and state experts pursued the dual paths of exploration and technical innovation. The search for domestic troves of potash led to a number of noteworthy projects, including the USDA’s failed program to extract potash from kelp beds along the California coast. Between 1916 and 1919 boats harvested hundreds of thousands of tons of kelp to derive a paltry amount of potassium at a high labor cost, to say nothing of its disastrous effect on the area’s marine ecology. The discovery of a scattering of potash deposits in the arid West tantalized fertilizer manufacturers but failed to deliver sufficient supplies.

The pursuit of new technologies to synthesize atmospheric nitrogen proved to be an even more costly and spectacular failed project in the short term, but one that had a long-term impact. The government-funded nitrogen fixation facilities in Muscle Shoals, Alabama were ineffective during the war, but they became an anchor of federal fertilizer experimentation and the starting point of the Tennessee Valley Authority during the interwar years. While these plants were not immediate successes, they planted the seeds of a longer commitment on the part of the federal government to the chemicalization of agricultural production in the United States.

The final approach to escaping the privations of the international law of the minimum was that of denial.

As experts began to suggest that losing fertilizer might threaten the nation’s crops, many questioned the scientific underpinnings of agricultural chemistry itself. This approach gained currency after America entered the war and a wave of anti-German sentiment swept the public. Some agricultural chemists contended that America’s rate of potash application was too high and reasoned that a brief interruption of potash imports would not substantially hurt production.

Other less sober observers argued that the German potash cartel had invented the market for their products from whole cloth, and that the value of potassium to crop production was not based upon solid science, but rather part of a “vast Teutonic conspiracy” that made American farmers slaves of the German potash cartel. Still others pointed to the fact that Germany was the international center of chemistry, and that those agricultural scientists who had trained in German universities had been brainwashed by German thinking at best, and at worst, henchmen of the Kaiser. Luckily, with the end of the war anti-German sentiment abated and so too did its influence on the public perception of scientific thought. Denying the importance—and indeed, even the scientific basis—of plant nutrition was a short-lived experiment that did not outlast the duration of the war.

Ultimately, America’s fertilizer resources were substantial enough and its participation in the war was short enough that starvation was never a genuine threat as it had been for the nations of Europe. And while the three pathways of diplomacy, discovery, and denial each failed during the four years of war, the urgency and fear that drove personnel within the American state to escape the international law of the minimum had lasting impacts. Perhaps the most enduring effect of America’s attempt to bolster its fertilizer supply chains during the war was that it enshrined the primacy of input agriculture in the United States.

By elevating what had been the commercial activity of the fertilizer industry into an imperative of the state, the war marked a decisive turn towards an industrial aesthetic in American agriculture and in turn, squelching dissenting voices that questioned the new fertilizer regime.