Source: Wiki Commons

Porridge

Sitopia: The Power of Thinking Through Food

Food is the tissue of civilization, weaving cities and countries together. In her essay, architect and food thinker Carolyn Steel provides a powerful prompt for us to reconsider the geographic and societal interdependency of urban centers and food-providing ecosystems and to find a way to move beyond the perils of the modern industrial food complex.

Talking Breakfast

What did you eat for breakfast? This seemingly simple question—which most of us can answer without thinking—captures the unique quality of the greatest unseen process shaping our planet. Eating is as natural to us as breathing, so we rarely stop to wonder how the bread, milk, cereals, fruit, bacon, or eggs on our plates happened to get there. Yet, when you come to think of it, the fact that most of us in the industrialized world get to eat three meals a day with very little effort on our own parts is something of a miracle; the greatest achievement, one might say, of industrialization. What is increasingly clear, however, is that the “miracle” has been achieved at a heavy cost: climate change, deforestation, soil erosion, water depletion, pollution, mass extinction, slavery, and diet-related disease are just some of the side effects of the way we eat.

The “miracle,” it turns out, is nothing of the sort. Rather, it is the result of the systematic externalization of the true costs of food production and the obscuring of the effort that it really takes to feed us. However great the breakthroughs that have given us industrial food—mechanization, monocultural production, chemical fertilizers, factory farming, chill chains, “efficiencies of scale,” just-in-time logistics—they have all had negative corollaries whose true effects have been systematically ignored. In this way, the illusion of “cheap food” (something that can never exist) came into being, a fantasy upon which modern economies, political systems, and urban civilization itself have come to depend. As the statistician E. F. Schumacher notes at the start of his seminal 1973 book Small Is Beautiful,

One of the most fateful errors of our age is the belief that the problem of production has been solved.E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. London: Vintage 1973, p. 2.

For a person living in a Western city, it would be easy to imagine that we’ve solved the problem of how to feed ourselves, and yet the very opposite is true: the way we eat is now the greatest threat to us and our planet.

How did we get here—and what are we going to do about it? To answer such questions, we need to return to the breakfast with which we started. Next time you sit down to eat, take a moment to stare at the food you are about to consume and try to imagine where it came from. Where were the oats in your cereal grown? Did they come from a vast monocultural field, or from a small, mixed-use farm? Were they grown chemically—that is, with large doses of artificial fertilizer or pesticides—or organically, in nutritionally rich, living soil? And what of the milk you poured on it? Did that come from grass-fed cows grazing in open fields, or from animals kept permanently indoors and fed on grain that we ourselves could have eaten? Or perhaps you used almond milk, in which case, did it come from the desertified plantations of California? And what of the sweetener you used? Was it honey from local hives, or sugar from vast refineries made from cane grown in the tropics? Do you know if the people who produced it were paid a living wage?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

As such an exercise soon makes clear, there is nothing simple about food, even an innocent-looking bowl of porridge. Every bite has vast implications for the shaping of landscapes, ecologies, societies, economies, trading patterns, living standards, power structures, and cultural attitudes. We live in a world shaped by food: a place I have called sitopia (from the Greek sitos, meaning food, and topos, place). Yet by failing to value food—expecting it to be cheap—we have created a “bad” sitopia: one so bad that it threatens our very future.

The morsels of food on our plates are emissaries from other worlds, each bearing signs of the value we place on them. Did the production of the plate of food in front of us make the world better or worse? Eating is an inherently political act, as well as an ecological and ethical one; there is no such thing as amoral food, any more than there is a free lunch. Once we have realized this, eating becomes a very different activity, one that we can no longer do “without thinking.” This new awareness is one we can harness for good, since most of us choose how we eat. Food, we realize, represents power.

Food and Power

The fact that food and power are inextricably linked would not have been news to our ancestors. We humans evolved through our shared need to eat: everything from language, economics, trade, politics, and religion sprang from it. For those of us who live in modern cities, it can be hard to imagine what life was like when food was omnipresent in people’s minds. For our hunter-gatherer forebears, the tasks of gathering, hunting, cooking, and sharing food were woven into the everyday fabric of life. Yet it was the advent of farming that cast food production as a conceptual problem, catapulting it to the status of prime shaper of civilizations.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Although hunter-gatherer societies revolved around food, tasks related to its production were so embedded as to be indistinguishable from the rest of life—which is one reason why the concept of “work” was virtually unknown in such communities. Urban-agrarian societies, on the other hand, required new structures and processes to deal with the complexities of farming and the seasonal tasks of sowing, growing, reaping, processing, and storing their new staple, grain. Writing and money were two crucial outcomes of this development, as were social hierarchies that distinguished for the first time between feeders and fed, farmers and consumers, rural and urban.

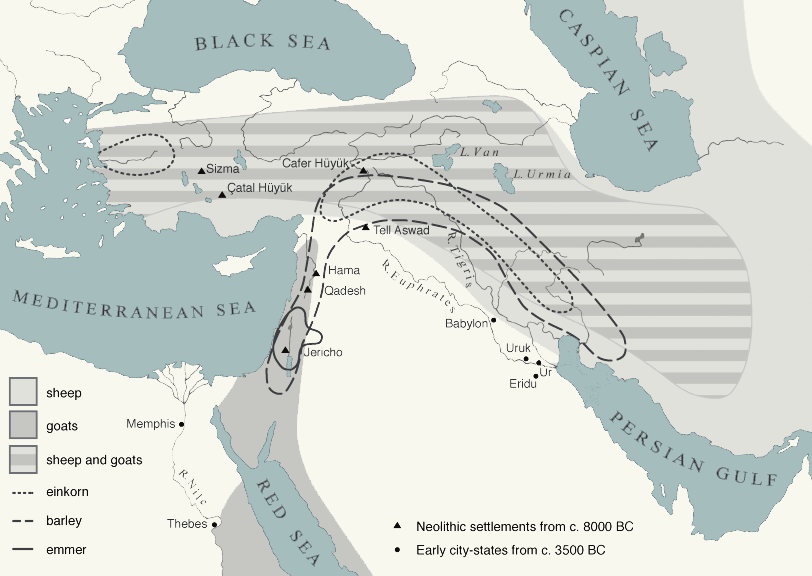

Although farming was far harder work than hunter-gathering, its one great advantage was the ability to produce a food surplus that could be stored through the year and so used to feed large non-food-producing populations.The archaeological evidence suggests that early farmers lived shorter lives than their hunter-gatherer counterparts, were shorter in stature, and suffered worse health. See Tom Standage, An Edible History of Humanity. London: Atlantic Books, 2009, pp.16–19. Cities and agriculture coevolved for this reason, and the world’s first urban settlements—the Sumerian settlements of Ur, Uruk, Kish, and Nippur, situated on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates—were effectively city-states: compact urban centers surrounded by dedicated farmland. Although they grew rich by exporting grain, such cities remained small enough to feed themselves off their own supplies, forging an urban blueprint that, for many, remains the ideal.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Most preindustrial settlements followed this basic pattern. Towns and cities were generally small and all roads led to the central market square, which was the heart of all commercial and public life. Most cities were built on rivers, which provided them with fresh water, fish, and a handy waste-disposal facility. Grain was grown out in the countryside, yet close enough to the city to make the transport of the relatively bulky, low-value food economical, while sheep and cattle, which could walk to market, were often grazed farther away. Most households kept pigs, chickens, or goats, which could be usefully fed on household scraps. Fruit and vegetables were grown on the city fringes, where they could benefit from “night soil” (animal and human waste) that was carefully conserved to be used as manure. Most cities, in short, had largely local, circular food economies.

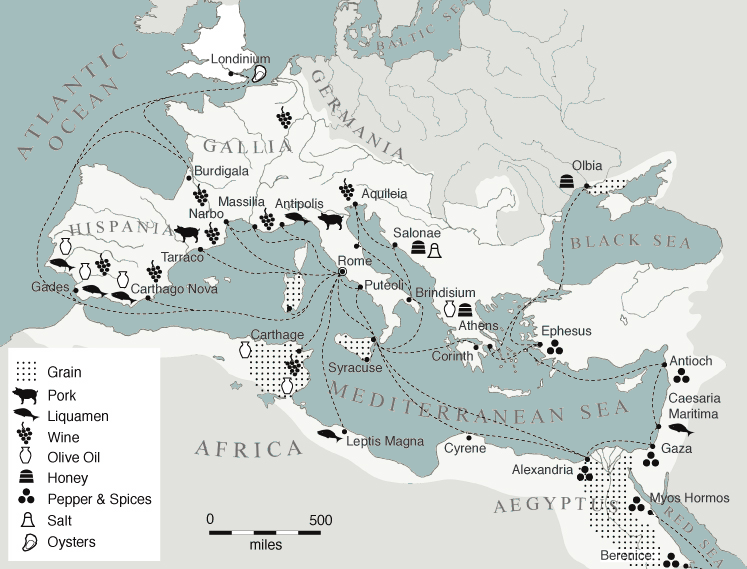

The city that bucked the trend was, of course, ancient Rome. As the world’s first “consumer city,” its vastness—with some million citizens by the first century BCE—meant that it had to do things differently. At its height, Rome was importing grain, oil, wine, ham, salt, honey, and liquamen (a popular fermented fish sauce) from all over the Mediterranean, North Atlantic, and Black Sea. Rome, in short, fed itself via what we would now call “food miles,” a strategy made possible by its command of the sea, over which was far easier (and about forty times cheaper) to transport food than overland.See Neville Morley, Metropolis and Hinterland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 65. With such staples pouring in from abroad, local farmers were able to concentrate on producing luxury foods for the city: everything from fruit and vegetables, poultry and game to song birds, pond fish, and nut-stuffed dormice. This so-called pastio villatica (villa farming) made farmers a fortune, yet was ridiculed by Pliny the Elder and other philosophers, for whom it merely symbolized the capital’s decadence.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

It’s not hard to recognize ourselves in the mirror of ancient Rome. While the city sucked up the nutrition from distant lands, rich citizens worried about eating too much, yet as their appetites expanded, the capital increasingly struggled to feed itself, eventually succumbing to collapse as the soils of its North African breadbasket failed. Rome ended up eating itself to death, as we are in danger of doing.

Goodbye Geography

Rome ruled supreme as Europe’s greatest city until the nineteenth-century advent of railways transformed the way cities were fed. By making it possible to transport food quickly and cheaply over long distances on land, railways emancipated cities from geography, allowing them to grow far larger and in remoter locations than before. As the metropolitan carpet started to roll out, a matching agricultural one began spreading in the “European colonies,” as previously inaccessible territories such as America’s Great West were opened up to grain production. When some US stockmen had the bright idea of feeding the excess grain to cows, the feedlot system was born, creating a previously unthinkable commodity: “cheap meat.” Chicago became the meatpacking center of the world, and when a packer by the name of Gustavus Swift worked out how to get his beef to the East Coast in an edible state (by using refrigerated railcars, the start of the modern “chill chain”), all the essentials of our current food system were in place. Henceforth, cities would be fed not by intricate networks of small producers but by a small number of powerful companies with the scale to take “vertical control” of the food chain and the logistical capacities to match.

Today, the global food system is more consolidated than ever, with a handful of companies such as Nestlé, Walmart, and Bayer Monsanto commanding profits bigger than many countries’ GDPs and just three such corporations controlling 60 percent of the world’s seeds and 70 percent of its fertilizers and pesticides. As such statistics suggest, the methods employed by such companies are overwhelmingly industrial, meaning that crops are grown monoculturally with the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, rather than organically on mixed farms. Our quest for cheap food has turned us against nature, with disastrous consequences for the natural ecosystems without which we couldn’t exist.

Sitopian Economics

The way we eat is killing us and our planet—so what can we do about it? The most obvious first step would be to acknowledge that cheap food doesn’t exist. Food, after all, consists of living things—plants and animals—that we kill in order to live. To treat it as cheap is thus to devalue life itself. If we were to value food properly again—which is to say, to internalize its true costs—it would transform our lives, landscapes, and societies. Industrial farming in its current form would immediately become unaffordable, which, in reality, it already is. The true cost of good food—which is to say, food produced in ethical, ecologically friendly ways—isn’t cheap; yet it is the only basis upon which good, lasting societies can be built. Great civilizations of the past, including Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome, were based on slavery, and all ultimately exhausted the land on which they depended.See Carolyn Steel, Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives. London Chatto & Windus, 2008, pp. 270–73. Since our modern urban lives depend just as much on the land that feeds us as ancient lives did, such examples suggest that valuing and protecting the land—as well as those who farm and look after it on our behalf—is fundamental to the hope of humanity thriving and surviving.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

By paying more for our food, we would open up great opportunities for those who want to work in the food industry, which, as the millions already involved in the global food movement suggests, is plenty of people. In societies where food is valued, feeding people is a hugely rewarding way of life. This is a win-win scenario since, if we want to work with nature instead of against it in order to feed ourselves—as, indeed, we must—we’ll need far more farmers working and looking after the land, not fewer. Contrary to those who insist we can’t feed ourselves organically, the latest research suggests not only that we could, but that we could eventually do so without increasing the amount of farmland needed.A major 2017 study led by Dr. Adrian Müller of ETH Zurich’s Department of Environmental Systems Science found that, were we to halve our food waste and stop growing specialist animal feed, we could feed ourselves 80 percent organically using no more farmland than would be needed for “business as usual,” while another study by a team from the University of California pointed out that, if we invest in improving organic varieties and methods, the remaining “yield gap” will disappear. See Adrian Müller et al., “Strategies for Feeding the World More Sustainably with Organic Agriculture,” Nature Communications, vol. 8, art. 1290 (2017), http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-01410-w; and Tom Bawden, “Organic Farming Can Feed the World if Done Right, Scientists Claim,” Independent (UK), December 10, 2014, https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/organic-farming-can-feed-the-world-if-done-right-scientists-claim-9913651.html. To do that, however, we will need to eat rather differently—much less meat and dairy and wasting far less. Such aims are surely not beyond our grasp. We might adopt what the British farmer and journalist Simon Fairlie has called a “default livestock” approach, raising only the animals we could sustain on food waste, grass, and crop residues, much as they were raised in the past.Simon Fairlie, Meat: A Benign Extravagance. White River Junction, CT: Chelsea Green, 2010, pp. 35–43. Although organic veganism is the most low-impact way we can eat, we do need animals in our food system if we are to farm organically, since, as the British “father of compost” Sir Albert Howard has pointed out, farm animals make a vital contribution to the circulation of nutrients and to soil fertility.

There are some who say that, in order to “save” nature, we should intensify agriculture and build vertical farms in cities to release as much countryside as possible back to wilderness. First proposed by the American epidemiologist Dickson Despommier in the early 2000s, vertical farms already exist in Singapore, New York, and London, doing a brisk trade in microgreens sold to high-end stores and restaurants.Dickson Despommier, The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century. New York: Picador 2010. Yet, as vertical farmers themselves admit, such farms are not the answer to feeding cities in the future, since, apart from the vast amount of space needed to build them, the cost of growing staples like grain in towers simply doesn’t stack up. Vertical farms may be part of the solution, but they can’t escape the “urban paradox,” which states that, however much we imagine ourselves to be urban, our need for food means that, in a greater sense, we all still dwell in nature. Vertical farms are, in essence, the pastio villatica of our day.

Could lab-made alternatives to meat and dairy also be part of the answer? This latest trend from Silicon Valley is already big in the US, with start-ups like Just and Impossible Foods attracting billions in investment from the likes of Sergey Brin and Bill Gates. Impossible Burgers, vegan burger patties that mimic meat juices using a vegetable compound called heme (which also exists in animal blood and gives hemoglobin its name), are already popular in the US and went on sale in the UK in 2018. Google, meanwhile, is funding a Dutch initiative to “grow” meat protein in a lab, using bovine fetal serum to replicate muscle tissue to produce so-called cultured beef. Whatever your view of such projects, the question is whether we really want our future food to be made and owned by the likes of Google and Amazon. Control of food, as our ancestors knew, is power.

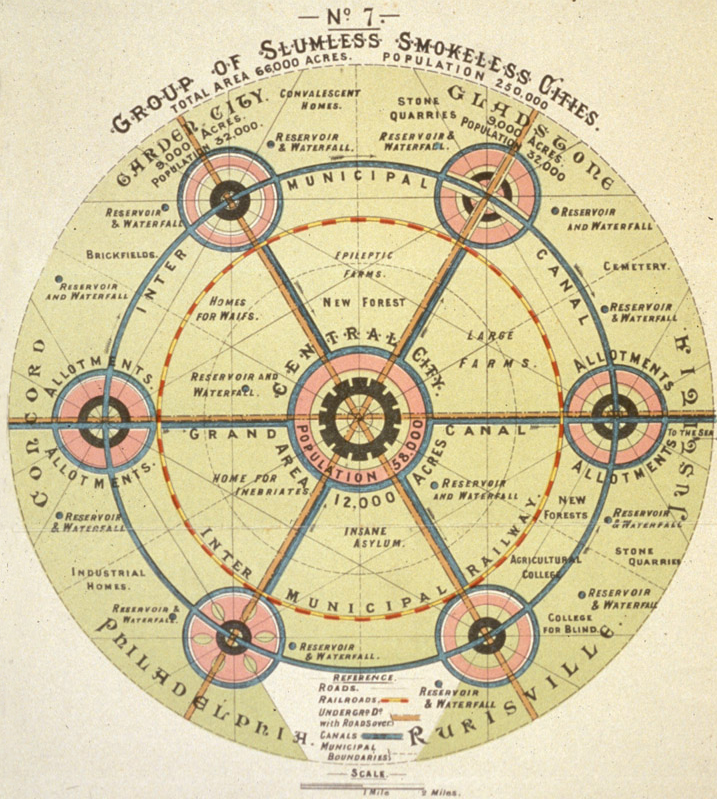

Perhaps the greatest lesson we can learn from our past is that big cities are hard to feed.For a fascinating discussion of the prerevolutionary Paris’s struggles to feed itself, see Steven Kaplan, Provisioning Paris: Merchants and Millers in the Grain and Flour Trade During the Eighteenth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984. Having witnessed Athens’s struggle to feed itself, both Plato and Aristotle concluded that the polis (Greek city-state) should stay small in order to remain self-sufficient.See Aristotle, The Politics, trans. T.A. Sinclair. London: Penguin, 1981, pp. 121–22; and Plato, Laws, V.738e, in The Collected Dialogues, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntingdon Cairns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987, p. 1323. London’s later dominance from medieval times onwards led utopians such as Thomas More and Ebenezer Howard to seek alternative models of urban development that struck a balance between city and country. More’s 1516 novel Utopia, Howard’s 1902 handbook Garden Cities, and Patrick Abercrombie’s realized 1944 London green belt all share the same idea: that cities should be limited in size and surrounded by countryside, not just to limit urban growth but to provide for our human needs for the benefit of both society and nature.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In a rapidly urbanizing world in which megacities such as Tokyo, Delhi, and Shanghai have populations upward of 24 million, such ideas arguably have more relevance than ever. Uncontrolled urban growth is predicated on the false premise that cities are easy to feed. The fact that we know this not to be true—that the hidden costs of industrial food systems are, in the words of one recent international study, leading to

a massive anthropogenic erosion of biodiversity and of the ecosystem services essential to civilizationGerardo Ceballos, Paul R. Ehrlich, and Rodolfo Dirzo, “Biological Annihilation via the Ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction Signaled by Vertebrate Population Losses and Declines,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 30 ( 2017), http://www.pnas.org/content/114/30/E6089.

—should urge us to rethink how we intend to live in the future. Using the lens of food, we need to consider what a landscape for human flourishing might look like in the mid-twenty-first century, by which time life will necessarily be lived under something like a steady-state economy. Such a way of life would seem to require that we weave city and country closer together. Future cities should be planned with farming in mind, while existing ones could be retrofitted, as André Viljoen and Katrin Bohn have proposed with their Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes (CPULs). As the geographer and town planner Patrick Geddes once said, we should

make the field gain on the street, not merely the street gain on the field.Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution (1915), Routledge 1997, p. 96

How we eat means more than simply whether our food tastes nice and makes us healthy; it is critical to the way we shape our lives and those of the other living creatures with whom we share the planet. Food is the great connector: the substance that ties us directly to the world’s living ecosystems, as well as to one another. By thinking and acting through food, we can seek solutions to our core needs as humans—for sustenance and society—and navigate the many complexities of modern life in order to thrive in a crowded, overheating world. By valuing food (and interrogating our porridge), we can work together to build a better sitopia.