8. Supreme Connections Meets Video City in Maryanne Amacher’s Intelligent Life

Musicologist Amy Cimini discusses Maryanne Amacher's (1938–2009) unrealized media opera Intelligent Life (1980–), in which the composer conceived of "synthetic listening"—a futuristic form of computationally augmented listening that was initially proposed in this work. Cimini contextualizes Intelligent Life as a popular mediatic form that drew its influences from cutting-edge scientific knowledge intermingled with popular culture in the 1970s and 1980s.

All at once, we are silent,

we are silent, …

Oh, what is happening?

No more shouts, this is it!

No more shouts, this is it!

—Georges Bizet, Henri Meilhac, and Ludovic Halévy, “The Toreador Song” from Carmen

And now we meet in an abandoned studio

We hear the playback and it seems so long ago

And you remember the jingles used to go …

—The Buggles, “Video Killed the Radio Star”

Almost everyone finds it quite incredulous that for so many years this Creative Response of Human Beings when in the presence of music was not RECOGNIZED AS SUCH and VALUED.

They have much trouble understanding this!

—Maryanne Amacher, Intelligent Life

i. introduction,

let’s just say that…

… you’re at home watching network television with the radio on; you’ve found the right frequency on the FM dial. Maybe it’s 8 p.m. or some similar slot typically reserved for prime-time programming. You might have even invited some friends for a viewing party. The way you still do for favorite shows and television events like games, debates, and televised performances …

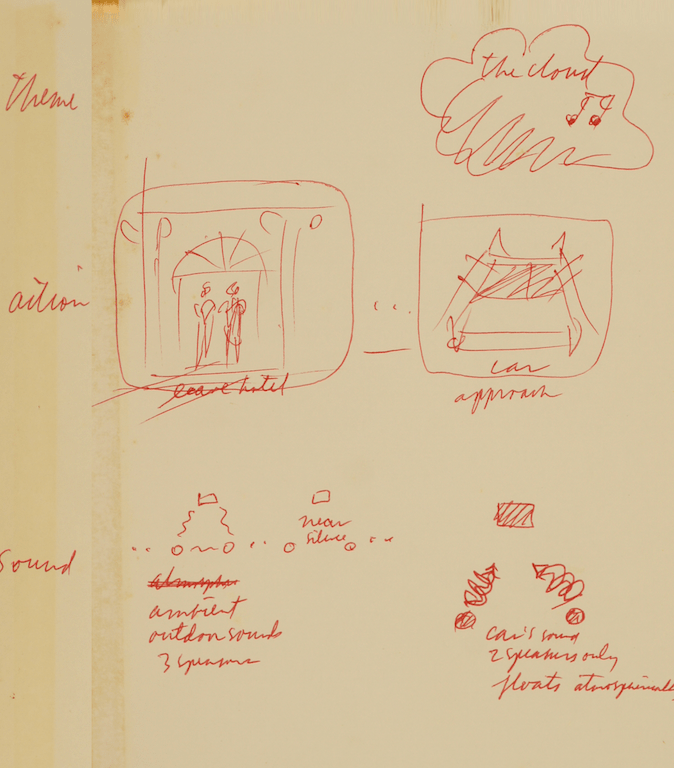

But what you’re watching is none of the above. From the TV you hear a pair of composer-scientists discussing far-out sounding technologies. Sounds like regular talk television. But as the characters walk toward their car, another sound appears in two speakers only. These sounds come from the car as it responds to their approach with a hum that becomes an atmospheric cloud of musical shapes. The car recognizes the characters’ footsteps and, in real time, supplies an ephemeral sonic world attuned to their movement toward the vehicle.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

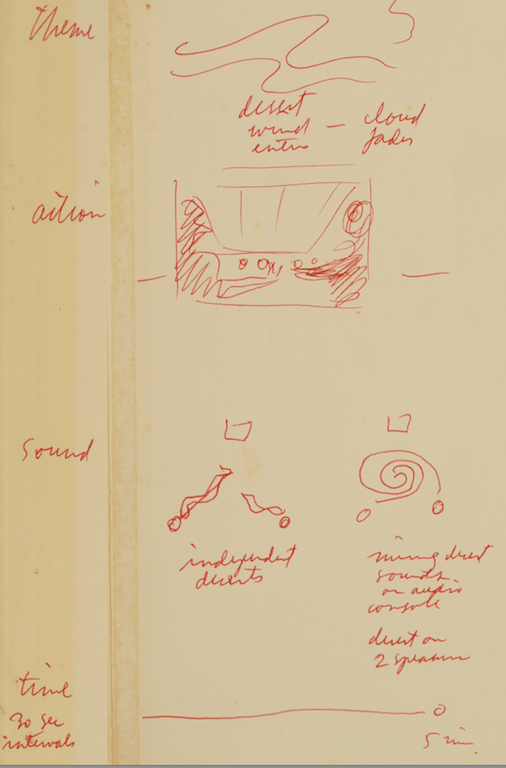

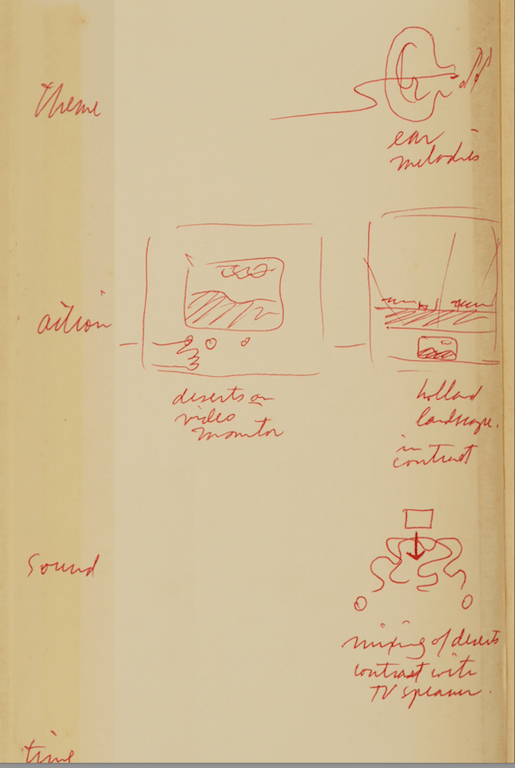

For the next few minutes, the pair keep talking about their work. As they explain why they’re so interested in interactive sonic design, things start to make a little more sense. One character dials in a long-distance transmission titled “The Desert.” You see a desert on screen via the car’s video console. The two speakers you’ve now come to associate with the car offer two different “desert” soundworlds that contrast those coming from the TV speaker. A cycling pattern of short, high-frequency tones bursts from the TV speakers. Still more tones come from the FM radio; everything fits together. The TV’s sound induces Maryanne Amacher’s well-known eartone music composed of distortion products that originate inside the cochlea. One character begins “ornamenting sounds” that originate in her companion’s ears; her real-time accompaniment is aimed at heightening his experience of dynamic, transforming intraural sensitivities. But the eartones she’s ornamenting are both the on-screen character’s and your own.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

ii. the opera

Welcome to Maryanne Amacher’s Intelligent Life.

You have just met Aplisa and Ty, two central characters in Amacher’s 1980s media opera. But you have done more than meet them. With no manual input devices, no strap-on sensors, no codified interaction procedures, no pre-use training session, you have just experienced how they listen.

The audience is able to experience the vivid sound world with the characters AS THEY CREATE THEM. In conventional television, audiences would only hear about them as the story ‘talked’ about them. —Maryanne Amacher, “Theater in the Home”

The year is 2021—the bicentennial of Hermann von Helmholtz’s birth—and the opera introduces Supreme Connections LLC, a music research and entertainment company. Aplisa is the president of Supreme Connections, and Ty is a lead investigator on one of the company’s major projects. In the first of Intelligent Life’s nine thirty-minute episodes, the pair finds all sorts of reasons to showcase Supreme Connections’ sound technologies.

Throughout Intelligent Life, Amacher delights in dramatizing science in the making through powerful gestures that open the laboratory to public investigation. Even romantic conventions serve this goal; when Amacher tells us that Aplisa and Ty’s relationship is “more than professional,” she links character development with technical exposition. Supreme Connections’ history emerges through their charming banter with didactic voice-over typical of the educational science programming of Amacher’s historical moment. At Supreme Connections, life, love, and work blend seamlessly together as Ty and Aplisa guide Intelligent Life’s at-home audience through how they listen and why.

An adventure series about our minds, Intelligent Life creates a space of expanded hearing and seeing to accomplish this. Imagination and understanding are charged by the intensity of a new image sound atmosphere. —Maryanne Amacher, “‘Media Opera,’ Concept Described”

Episode one explicates how Supreme Connections came into being. Forged amid the failure of algorithmic music recommendation services and a first-generation artificial intelligence that could compose in nearly any historical idiom, Supreme Connections proposed an alternative world of public media interactivity: “smart” technologies for the car and the home, enchanted architectures of customizable audio, “theme-parked cities”Ann Balsamo, “Digital Humanities Catalyzes Technological Innovation: You’ll Never Believe What Happened Next” (paper, Creativity, Cognition and Critique: Bridging the Arts and Humanities, University of California, Irvine, May 21, 2016). See also Malcolm McCullough, Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013, pp. 47–66 with predictable pleasure zones that respond to nuances of body, affect, and sociability with all sorts of original but also highly situated events of sound and listening. Amacher wanted to give her at-home audience precisely these kinds of experiences.

An enveloping, magical architecture in the home is created. The room becomes many new kinds of places. The result from the specific interplay composes between the TV image, TV sound and FM stereo sound. A completely new kind of theatrical experience is SHAPED, one that can not be created for stage production, movie theaters, conventional simulcast radio-TV or TV alone. —Amacher, “Theater in the Home”

Unlike conventional simulcasts, INTELLIGENT LIFE goes beyond enhancing sound fidelity, reproducing the same sound tracks as those of TV to make more lively, realistic experiences for the audience. It composes with the expanded dimension of the simulcast to better match some of them mind’s expanded sensitivity—to CREATE what is the story’s Theme. —Amacher, “‘Media Opera,’ Concept Described”

This magical architecture shapes the viewer’s awareness of their ongoing bodily engagement in the context of an aesthetic environment conceived to provoke certain kinds of explorations. The opera’s diegetic demonstrations call forth such awareness and invite the listener’s explorations to track alongside those of the on-screen characters. While Intelligent Life flirts with discourses of virtuality, the opera’s aesthetic goals are grounded in situated, embodied sensorial experience, unlike earlier concepts of the virtual staked on the separation of patterned information from any material substrate. Artists’ aspirations in new media in the 1980s and 1990s foundered in a number of ways. While personal computing was new and rapidly in transition, aspirations fueled by science fiction and 1970s technophilic hangovers “often outstripped existing technology and theoretical contexts,” as Simon Penny puts it.Simon Penny, “The Desire for Virtual Space: The Technological Imaginary in 1990s Media Art,” in Thea Brezjek (ed.), The Space and Desire Anthology. Zurich: ZHZK, 2011. In Intelligent Life, Amacher seems to have successfully played both ends against the middle. By composing for TV and radio, Amacher could depict Supreme Connections’ computational complexities without having to come face-to-face with deep computer-hardware engineering (or having to do so on an artist’s nonexistent budget). Working with existing TV and FM radio also meant she didn’t have to commit to new hardware that might lead to a technological dead-end or commercial backwater.

‘INTELLIGENT LIFE’ might be described as ‘media opera.’ It uses actual broadcasting media to create a theater in the home. In the tradition of ‘grand opera,’ it is designed as a unique occasion—dramatic, extravagant, extraordinary. —Amacher, “‘Media Opera,’ Concept Described”

A Media Opera Designed for television and Radio Simulcast. A musical occurring in the future. To be presented as a Multi-part series. —Amacher, “‘Media Opera,’ Concept Described”

Amacher calls upon a wide range of media forms to furnish opera’s expressive, historical, and theoretical context: grand opera, Hollywood “show” and “backstage” musicals of the 1930s, big-budget educational science programming of the 1950s, and marquee-name science fiction writers like Arthur C. Clarke and J. G. Ballard. Each of these touchstones equips forms of sense and experience associated with the dramatization of specialized artistic and technological knowledge. Science fiction fueled social and technological imaginaries; musicals offered the ecstatic “break into song” to enhance those imaginaries’ wildest moments. Backstage musicals, specifically, dramatize fast-paced work in the entertainment industry; educational broadcasts dramatize scientific demonstrations and carefully account for their in-home audience’s bodily awareness in front of television screens. Each form offers Intelligent Life familiar touchstones for character development, dramatic structure, and heightened moments of musicality. If Penny sees a paucity of contexts, Amacher sees a surfeit.

Episode one centers entirely on Aplisa and Ty. However, Amacher’s treatment introduces a number of wild characters who presumably would have appeared later in the opera, even though we don’t meet them in episode one. Take Ray Alto, for example. Amacher pulls Alto’s character straight out of Ballard’s dystopian short story “The Sound-Sweep.” Not unlike Intelligent Life, Ballard’s tale centers on musical entertainment of the future. Alto’s world is so noisy that all music is neurophonic; his ultrasonic music resounds only in the brain. All of this (including Intelligent Life’s setting of Video City) comes straight from “The Sound-Sweep” playbook:

Ray Alto, doyen of the ultrasonic composers is busy designing his totally neurophonic circuits and preparing his production of J.G. Ballard’s classic story, THE SOUND SWEEP from the late 1960s. RAY ALSO is currently director of the Psycho Sound Research for the vast complex VIDEO CITY.Amacher, Intelligent Life, Character Treatment

Nested in Intelligent Life, “The Sound-Sweep” invites all sorts of comparisons and emphases. After all, Ty and Aplisa’s soundworld is very different from Ballard’s. In the world of Supreme Connections, Alto’s neurophonic music would resound alongside music for the inner ear, music for the skin, music for the body, and all kinds of interactive sonic environments. And Alto’s production would, like the entire opera, reach home audiences via TV and FM radio, both of which Ballard’s Video City would have obsolesced. While Intelligent Life embraces “The Sound-Sweep” as its theoretical context, the story is only partially up to the task. In this essay, I am going to take a chance on this cryptic intertext.

The intrusion of “The Sound-Sweep” into Intelligent Life throws the opera’s treatment of listening in computational environments into sharp relief. At the same time, however, this intertext suggests how questions are crosscut by historical formations of gender, sex, desire, and embodiment. Though these formations do not necessarily form Intelligent Life’s major plot points, they structure the opera’s thematic world in other ways. The opera points outside itself in order to invite these themes back into the diegesis for further, ceaseless elaboration.

And so, I’m going to write about a character that we never meet and a production, that, in episode one, we never hear. But I still accept Amacher’s shimmery invitation to try thinking and listening between the story and the opera. Writing about Intelligent Life is never without its risks.

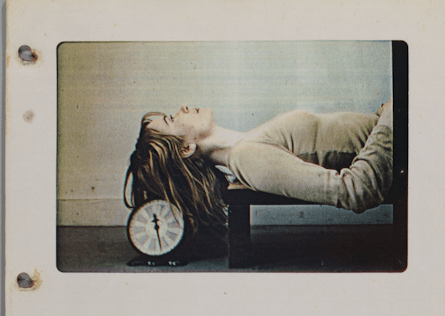

Amacher’s 1980s treatment spans about 150 pages and includes six sections. Below, you can see how Amacher sets up her table of contents (the capitalizations are her own). This essay began with drawings from the sound treatment for the pilot episode. Yet, Amacher did not draw them (they are not in her handwriting); I don’t know who did.

PREMISE: THEATER IN THE HOME “MEDIA OPERA,” Concept Described TIME AND AMBIENCE FOR THE STORY CHARACTER TREATMENT BACKGROUND TO THE STORY’S MUSICAL INTRIGUE PARTIAL TREATMENT FOR A PILOT STORY SOUND TREATMENT WITH STORY ACTION FOR PILOT STORY STORYLINES FOR EPISODES 2 AND 3

It’s not that I’ve chosen not to write about the whole of Intelligent Life; rather, it’s that there’s not a bounded whole thing to write about. This essay could have begun with an Intelligent Life proposed to De Appel in Amsterdam in the early 1980s. There, Amacher captures the opera’s interimplication of audience and on-screen action: “separated in space, Intelligent Life observes minds together in time. Music evolves, listening minds separated by space, together in time.” In that version, long-distance live transmissions of performers in remote locations would have complemented the opera’s scripted action. Writing about Intelligent Life means writing, in some sense, about “opera.” But it also means writing about how Amacher puts things together in order to dramatize how sound ceaselessly exceeds itself. Amacher points relentlessly to sound’s ongoingness or continuation elsewhere across time, space, and social location; ways of listening, forms of intersubjectivity, and concepts of sound function differently along the way. As Talal Asad notes, many modes of critical inquiry want to see and hear everything.Talal Asad, “Free Speech, Blasphemy, and Secular Criticism,”

in Is Critique Secular?: Blasphemy, Injury, and Free Speech, by Talal Asad, Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, and Saba Mahmood, pp. 14–57. New York: Fordham University, 2013. Intelligent Life does not comply. Perspectives on the opera will be partial or they will be nothing at all. Perhaps, then, it’s best to assume that Alto’s hypothetical production remains, throughout Intelligent Life, unheard but in progress.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

iii. doyens, divas, and sweeps

“The Sound-Sweep” appeared in the pages of Science Fantasy in 1960. At that time, Amacher was finishing up her undergraduate training at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Soon she’d begin work on “Adjacencies” (1965) for percussion duo and quadraphonic sound projection. This would be her last notated work for orchestral instruments for some time.

“Adjacencies” was to be part of a multipart collection of works from the early to mid-1960s titled AUDJOINS, a Suite for Audjoined Rooms. The suite would have staged ensembles in built space. (“Adjacencies” is the only known extant score of that series.) Indeed, Amacher’s added “u” to the word suggests architectural jointures and contiguities held in place by sound, listening, and their coupling in the aural. Composing for built space occupied Amacher throughout her life, not least via Intelligent Life’s magic architecture.

In Ballard’s story, however, the dynamic, clangorous sounds of Adjacencies percussive architecture would no longer exist. His is a punishing soundworld rocked by omnipresent, stomach-turning industrial noise. Sounds leave residue in built spaces, and excessive sonic residue makes people sick and topples buildings when it accumulates. The story’s viciously stratified socioeconomic world is organized, in part, around the now identical dangers of music and noise. The entertainment conglomerate Video City has monopolized the production of ultrasonic music, which leaves no traces, unlike audible music. The frequencies used by Video City’s ultrasonic composers are so high they don’t leave any corrosive residue; neurophonic music bypassed the auditory pathway and goes straight to the brain, careening around inside each listener’s heads. Ballard humorously refers to these frequencies as “P” and “Q” notes. Every instrument has an ultrasonic counterpart—except the human voice. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Ludwig van Beethoven, Arnold Schoenberg, and other marquee figures from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries live via ultrasonic arrangement. Each day, a phalanx of so-called sound-sweeps clean public and private spaces and deposit their sounds in the sonic dump, a kind of shanty town where sweeps also live. Sound-sweeps live amid the dangerous din from which they save everyone else.

The story orbits around the high-ranking Video City composer Ray Alto, the long-obsolescent opera singer Madame Gioconda, and Magnon, the sound-sweep who works for both of them. Each power-differentiated position entails different way of listening: Alto works with ultrasonics, Gioconda yearns for a resurgence of non-ultrasonic vocal music, and Magnon, unlike other sweeps, can hear all the sonic residues that he is charged with cleaning. Except for the story’s omniscient narrator, Magnon is the only one who can hear everything in the story’s soundworld. While for the most part it isn’t clear where to locate the observer in relation to what is being observed, Magnon is quite a different story.

Though he could do many things with his exceptional listening, Magnon uses his ears to serve Gioconda. She’s plotting a comeback concert and needs Magnon’s help collecting old sonic residue in order to blackmail her ex, Video City’s CEO, Hector LeGrande. Magnon takes Gioconda to the sonic dump, where they scour the shanty town for residue of LeGrande’s voice. Her plan: threaten LeGrande with dirt so damning that he has no choice but to broadcast her comeback performance over Video City’s networks. Maybe the voice will win out over ultrasonic music after all. And Video City is the only game in town.

Magnon’s hopeless infatuation with Gioconda has everything to do with misrecognized parallelisms involving listening and voice. Ultrasonic music made Gioconda’s voice technologically obsolete. And Magnon hasn’t spoken since the age of three, when, we are told, his mother struck his throat and permanently damaged his larynx. Though both characters have in some sense “lost their voices,” their respective losses signal very different social processes. But in Ballard’s merciless rendering, Magnon cannot tell the difference: he stakes the resolution of his childhood trauma on Gioconda’s comeback. Helping her restore her voice will not only restore his voice but also make up for the lack of maternal love that took it in the first place. Ballard stretches the reader’s suspension of disbelief when Magnon actually regains his voice, partway through the story. Like his exceptional listening, this goes unexplained.

For years, he’s been pretending to sweep boos and jeers from Gioconda’s home, even though he knows that they’re in fact all in her head. The better his placebo works, the more woozily erotic Magnon’s attachment becomes. His entanglement with Gioconda stems from his position in Video City’s global labor market, and his resultant infatuation cannot be disentangled from broader concepts of work in the service sector involving customer care and satisfaction. Through Magnon, we get a glimpse of how service work responds to changing conceptions of sound, technology, and media in Ballard’s fictive world.

Ballard’s tight focus on the blackmail plot pushes the story’s vicious structural inequalities into the margins. We don’t meet any other sweeps; we also don’t meet any other singers who’ve been similarly crushed by ultrasonic music (consider, for example, that 1960s R&B, soul, and gospel traditions are nowhere to be found in Video City). It’s hard to imagine the commanding, eminently detestable Gioconda restoring vocal music on anyone’s behalf other than her own, even though she could clearly manipulate LeGrande to such an end. Magnon’s capacity to hear sonic residue also suggests all sorts of insurrections. Yet, in addition to having sex with her, Magnon imagines becoming Gioconda’s manager after her return to the stage. This might be a victory for Magnon, but would certainly be a loss for other sweeps. Amid a resurgence of vocal song, they’d have considerably more work to do in order to keep pace with the voice’s sonic residue.

Magnon also works for Alto, the ultrasonic composer, whose successes parallel Gioconda’s failures almost point for point. Unlike Gioconda, Alto has figured out how to make nineteenth-century Euro-American traditions work within Video City’s ultrasonic industry. He updates Western art music for ultrasonic instruments and has even written a symphony of his own, titled Total Symphony. Gioconda, on the other hand, simply will not go quietly. Once her voice is made obsolescent, she becomes grotesque in almost every way imaginable: fat, drunk, coked out, self-obsessed, delusional, and manipulative. Ballard doesn’t miss a sexist beat. While Alto gets paid to make music in a functional studio, Gioconda lives in an old soundstage surrounded by iconic props from opera staples: she sleeps on Desdemona’s bed, looks at herself in a mirror from L’Orfeo, cooks on a stove from Il Trovatore, and stuffs newspaper and magazine cuttings into a wardrobe from Le nozze di Figaro.

Magnon lets Alto in on Gioconda’s scheme. The two plan to put her on closed-circuit television; Gioconda will think she is being broadcast, Video City’s ultrasonic monopoly will go unchallenged by the human voice, and LeGrande will be none the wiser. But Gioconda gets to LeGrande first; Alto reports on her pre-climactic call after the fact. Though we never hear what was said, Gioconda’s threats work. LeGrande gives her free reign to book her comeback concert on a Video City program of her choosing. Alto convinces Magnon that, after years of neglect, Gioconda’s voice is shot and for her own good, no one should hear her. When she chooses to sing over the premiere of Alto’s Total Symphony, he instructs Magnon to sweep away her voice as she sings; she won’t know that no one will actually hear her. Of course, Magnon thinks Alto is wrong about Gioconda’s voice. And as the concert’s designated clandestine sweep, he’s in the just the right position to prove it.

Things do not go according to plan. Anticipating imminent fame—and having gotten what she wants—Gioconda leaves Magnon a nasty farewell via sonic residue: “Go away you ugly child! Never try to see me again!” Magnon arrives at the concert with Gioconda’s cruel goodbye ringing in his mind’s ear. With his sonovac running, only he can hear her when she starts to sing. She performs the bullfighter Escamillo’s “Toreador Song” from Georges Bizet’s Carmen. Presumably, she’s lost her high range and can no longer deliver Carmen’s mezzo-soprano arias; with Escamillo, she now sings a bass-baritone role. Ballard’s narrator pulls no punches:

The voice exploded in his brain, flooding every nexus of cells with its violence. It was grotesque, an insane parody of a classical soprano. Harmony, purity and cadence had gone. Rough and cracked, it jerked sharply from one high note to a lower, its breath intervals uncontrolled, sudden precipices of gasping silence which plunged through the volcanic torrent, dividing it into a loosely connected sequence of bravura passages.J. G. Ballard, “The Sound-Sweep,” in The Complete Short Stories of J. G. Ballard. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

Shocked, Magnon trips over the sonovac power cord. Once it’s unplugged, everyone can hear Gioconda. In Carmen, Escamillo’s song taunts the bull and whips the on-stage audience into an erotically charged frenzy of anticipation. Ballard’s scene offers parallels. In “The Sound-Sweep,” Gioconda’s “Toreador Song” taunts Magnon and whips her live audience into a disgust-laden frenzy as they flee the hall, horrified by the sound of her voice—or, by the sound of any music that isn’t neurophonic; it’s hard to tell, actually.

We don’t really find out what happens to Gioconda after the concert. Instead, we follow Magnon as he drives away, using sonic residue to blot out his memory of Gioconda’s voice. Parallelisms continue to accumulate. Gioconda was once tormented by remembered boos and jeers; he will be tormented by the memory of her insults. In this stomach-turning symmetry, the violence of technological obsolescence rolls downhill to clobber the story’s most vulnerable character—on whose work, of course, the very existence of Video City has long depended.

iv. meanwhile, back at supreme connections …

Intelligent Life casts Alto’s ultrasonic music in a far different audiovisual world. In Intelligent Life, Video City no longer monopolizes musical entertainment. Alongside Supreme Connections’ concern for interactive, embodied listening, Alto’s research might function much differently. But Supreme Connections has its own noisy mess to deal with.

The Old Warner Brothers, and a number of other companies of this kind have totally collapsed because they did not anticipate the power of NEW SONG and the consequent demands of the increasingly conscious listener. They continue to produce their silicon pattern developers without taking into account the CREATIVE RANGE OF MUSIC SENSITIVITY or the BIOCHEMICAL EFFECTS OF THIS MUSIC. Their securities were completely tied up in 1st Order Artificial Intelligence products—such as Pattern Variation Developers. —Maryanne Amacher, “Background to the Story’s Musical Intrigue”

Industrial noise isn’t the problem; composers are. For years, they kept making computers better and better at composing in the styles of Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Steve Reich, and so on. All this under the assumption that creativity lies with the work of composition. But it is listening that paid the price.

This began with computer software for the home—designed to give people the pleasure of composing. … i.e. modifying existing patterns in Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Reich—making subtle or not so subtle variations and developments of this music. —Amacher, “Background to the Story’s Musical Intrigue”

This concept of computation prioritizes formal manipulation of symbols over their enaction in a listener’s lifeworld. Amacher seems to impugn a concept of intelligence staked on the manipulation of symbolic tokens in some abstract historical space as opposed to an ongoing engagement with the material world and the embodied listener, specifically. This was a mess of the music industry’s own making.

Lots of commentary links “The Sound-Sweep” with the Buggles’ song “Video Killed the Radio Star,” seeking parallelisms between Video City and MTV. The song’s performative “you” could be Magnon, Gioconda, or Alto. “New technology” might as well refer to Alto’s atelier, and this “abandoned studio“ sounds an awful lot like Gioconda’s soundstage:

They took the credit for your second symphony

Rewritten by machine on new technology

And now I understand the problems you can see

…

And now we meet in an abandoned studio

We hear the playback and it seems so long ago

And you remember the jingles used to go …

Click here to insert text for the typewriter

However, these analogies don’t quite work. MTV’s launch doesn’t track easily with Video City’s fictive ascendance. Video City doesn’t exactly kill Gioconda so much as it slowly kills the workers who maintain the soundworld upon which its profitability relies. And Intelligent Life suggests that we ought to be concerned not so much with individual “radio stars” as much as with attenuated ways of listening across a far vaster social field.

Music had come to mean the ‘nod and tap’ recognition of secure tunes, melodies and shapes prepared ages ago. What developed was a music sustaining itself through memory patterns. —Amacher, “Background to the Story’s Musical Intrigue”

Although “Video Killed the Radio Star” sketches little story about AI composers, the Buggles’ later single “Vermillion Sands” takes a snarky guess at what their music might sound like. After all, the earlier single’s earwormy chorus seems to downplay the narrative that appears to unfold during the verses. In “Vermillion Sands,” however, we are to find out the Buggles are not a band at all, but instead a computational process doing its best to mash together different styles in some novel way. The seven-minute progressive rock nightmare that is “Vermillion Sands” begins with bulbous synth bass that, after two minutes, drifts toward rag-ish syncopations and then returns to a wash of watery synth strings punctuated by the opening’s burpy bass. It bears underscoring that the Buggles’ hypothetical computation aesthetics begin by imitating African diasporic music. A long outro returns with crashing waves, followed by another syncopated bridge, and closes with a bloated imitation big band.

The unsettling truth was that these fragments were snatched from the great fragments of MUSICAL MEMORY! —Amacher, “Background to the Story’s Musical Intrigue”

Though it would be easy to imagine that Ty and Aplisa’s Supreme Connections would have had to remediate a soundworld full of music like this, Amacher calls upon science fiction much differently. In episode one, Ty muses on science fiction, listening and “The Sound Sweep:”

Yes, Science Fiction was a little like J.G. Ballard’s “Sonic Dump.” It held all the residues—still sounding, that everyday experience had to ignore, could not hear or talk about. Our receptors became a “swept away” notion. Coded to be active, their existence was suppressed in every day language and their ENERGY terribly repressed by the sensory experience provided by the technological media at the time. Yet, receptors WERE THERE, ready to respond, bind and recognize—coded to enjoy and learn from stimuli—they WANTED to feel, but were kept dormant.Amacher, Partial Treatment for a Pilot Story

In Intelligent Life, Ballard’s story becomes part of the opera’s fictive historical record. Ways of listening once lost to musicians and composers lived on in literature, as though awaiting rediscovery by future musical practices. Ty’s analogy focuses on the sonic dump.

While Ballard dramatizes Gioconda’s and Magnon’s losses in a fight they could not possibly have won, Ty’s comments foreground Magnon alone. In Magnon, obsolesced listening lives on in the present. Amid scouring the dump for specific sounds, Magnon relies on ways of listening that Supreme Connections will seek to remediate. His listening—not Gioconda’s voice—points the way toward restored variegated aural sensitivities. While Magnon instrumentalizes the sonic dump on Gioconda’s behalf, the changes they’re trying to extort remain immanent to the site they treat like trash. Ty’s interpretation also reworks Magnon’s desire for Gioconda. In his version, desire becomes immanent to listening itself. Within Amacher’s characteristic all-caps ebullience, Ty underscore that “receptors WANTED to feel.” Untethered from oedipal attachment, ways of listening might channel desire in all sorts of directions. And so, by 2021, Supreme Connections works on the side of the perceiver.

What else could composers do with a personalized melody that could be created by machine intelligence? —Amacher, “Background to the Story’s Musical Intrigue”

But Intelligent Life’s soundworld still requires major cleanup. One member of Aplisa’s team actually works to remediate old, crumbling sound installations at Vermillion Sands. Though they were intended to be permanent, these fictive sound installations were not wired with machine awareness of bodily change.

While minimalist sculpture during Amacher’s time offered enlarged situations to account for multiple scales and ranges of bodily experience, Amacher seems to ask even more of sound installation practice.

In “The Sound-Sweep,” noise abatement yields a brutally attenuated approach to music and sound. But in Intelligent Life, Alto’s “ultrasonic research” would have to unfold alongside real-time computational interactivity of many kinds. Supreme Connections complements his intense neurophonic experiences with relational sonic environments built, in real time, from the interactions of diverse multimodal components. Rather than sweep away environmental sound, Ty and Aplisa enhance its desirable features using the jetsono, a sprayer device that adds three-dimensional sonic shapes to the built environment. And while Video City peddles ultrasonic versions of nineteenth-century masterworks mired in discourses of aesthetic autonomy, Intelligent Life subordinates those very same works to the many ways of listening they might meet along the way, including listening in different atmospheres, on different planets, under the ocean, and by non-human life forms. Real-time accounting of bodily change and relational, networked ways of listening mean that we are never not imagining how our listening affects others’ differential sensitivities.

All in all, the Ray Alto of Ballard’s story doesn’t come off all that great. Though he’s clearly sick of shilling for LeGrande, he’s no better than Gioconda or Magnon at imagining meaningful, far-reaching changes for Video City. For him, protecting the status quo goes hand in hand with controlling Gioconda. The story’s socioeconomic order can only tolerate so many ways of listening. Silly though it may sound, one can only hope that working at Supreme Connections would have changed Alto for the better.

As Amacher puts it in an early proposal for Intelligent Life, scenes taken from Ballard, Arthur C. Clarke, and Olaf Stapledon might “emphasize certain themes” of the opera.

In Amacher’s opera, Alto’s production coheres amid sound technologies that Ballard obsolesces. Supreme Connections has already redressed their obsolescence on listeners’ behalf. Both works are in some sense “about” the listeners’ engagement with their own ongoing bodily experience. In “The Sound-Sweep,” that engagement yields myriad misrecognitions and toxic attachments. In Intelligent Life, it yields shifting and situated embodied knowledge. And so perhaps Intelligent Life includes, in its many contexts, a hypothetical future for the world of “The Sound-Sweep” that offers new ways of listening not only to Alto, but to Magnon and Giaconda as well.

end scene

Short portions of this essay appear in:

Amy Cimini, “In Your Head: Notes on Maryanne Amacher’s Intelligent Life,”

Opera Quarterly vol. 33, nos. 3–4 (December 2017), pp. 269–302.

For an expert reading of “The Sound-Sweep” in relation to Euro-American musical avant-gardes, please see:

Sylvia Mieszkowski, Resonant Alterities: Sound, Desire and Anxiety in Non-realist Fiction. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2014.