Anna Zett 2015

Sleeping in Public, Working Like Babies

Sleep is a state where we disengage from the world around us both physically and sensuously. Artist Anna Zett discusses how this disconnection plays a role in our relations to capital, the pharmaceutical industry and our cognitive plasticity, exploring the disorders that alterations of sleep propagate.

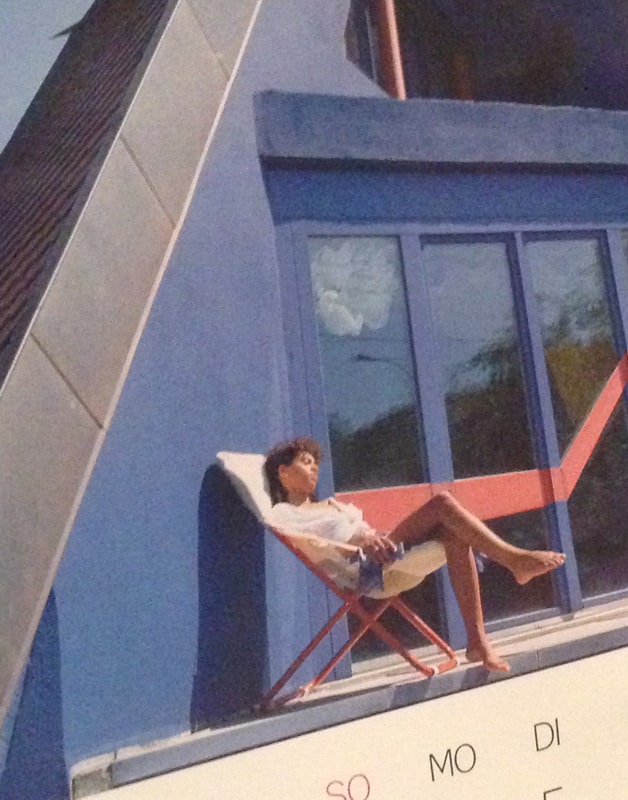

Seven years ago, then living in a strange non-neighborhood between Mitte and Kreuzberg, very close to where the Berlin Wall used to separate East and West, I put up a huge photo calendar on our kitchen wall, titled SCHLAF 1992 (Schlaf meaning sleep). The purpose of the calendar, produced by the pharmaceutical company my mother had once worked for, had been to advertise a so-called “hypnotic,” aka ‒ a sleeping pill. Each page of the calendar showed the brand name of the drug and a photo of a woman sleeping in weirdly uncomfortable positions away from home – in office spaces, in front of tourist attractions, in different cities all over the world. Visitors who saw it hanging in my kitchen did tend to comment on it and many agreed that it was fucked-up in an interesting way. It wasn’t cynicism that made me want to decorate our home with a pharmaceutical ad; in retrospect I would say that I kept it and put it up on the kitchen wall so that I could write about sleep, capitalism, and the early nineties five years later.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In her book Testo Junkies, Beatrice Preciado describes how contemporary subjectivities are defined by the “substances that supply their metabolism.”Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkies: Sex, drugs, and biopolitics in the pharmacopornographic era, trans. Bruce Benderson. New York: Feminist Pr, 2013, p. 35. As psychotropic substances and biotechnologies have morphed into widely accessible and marketed consumer goods, we have become able to directly manipulate our embodied selves on a molecular level. Legal and barely-legal drugs have become powerful tools for self-enhancement and self-care.See also: Emily Martin, “The Pharmaceutical Person,” BioSocieties 1, no. 3 (2006): pp. 273‒87. They are assigned the power to create new selves inside of us and to reanimate old selves that are not alive in us (anymore), or as Preciado put it: “We are half fetuses, half zombies.” I am not sure who is and isn’t included in this “we,” and, personally, I have started to avoid synthetic pharmaceuticals, especially the legal ones. There are many ways to politicize your metabolism, many ways to experience (a fantasy of) the present on a molecular level.

When I grew up in Leipzig in the 1990s none of the adults around me had a clue how the newly installed system called “capitalism” actually worked in practice (although not all of them admitted that). Just after the border opened my mother, a chemist, quit her job in a hospital lab and found a new job as an account manager in a Swiss pharmaceutical company doing field service in the new East German market. My father kept working as a psychiatrist in the same public – later privatized – hospital. For me, a kid from the first generation to start school after the “turn,”In German Wende (turn, transition) became the general term for the transformation starting in 1989/90. the new era was defined by weirdly insecure teachers, lots of scaffolds to climb on, and heaps of amazing garbage on every street corner. As I grew older, the transformation that I witnessed my parents dealing with and trying to adapt to was that of a formerly state-owned health care system that had to be completely restructured to fit into a neoliberal market economy. For my mother the Westernization couldn’t go fast enough. My father, however, preferred to take it slow, spending five minutes of every hour reflecting on the present and the remaining fifty-five to tell detailed stories about all kinds of characters from all kinds of eras in the past. But what both of them kept bringing home from their everyday adventures in the new system was free stationery decorated with [pharma-product®]. After both my parents had died (of different diseases, but strangely both located in the brain) ‒ and after I had become an artist, the calendar SCHLAF 1992, which I had found among the thousands of useless things my father had left behind, came to my mind again. Twenty-five years after “I’ve been looking for freedom,”The song that David Hasselhoff famously performed on the defunct Berlin Wall in 1989. I needed to revisit those transformative years again, only now from my own perspective.

In the meantime, in the art world, a new ideology – Neomaterialism – had established itself or at least had become very popular. As the term kept decorating countless blogs, conferences, and art blurbs, it got linked to so many different associations, that it became almost impossible to define its meaning.[Give it a try]( http://neomaterialism.tumblr.com/), accessed October 18, 2016. The primary function of neomaterialism might have been to host the notion of a neoliberal materialism, one that succeeds both communist materialism (production-focused) and capitalist materialism (consumption-focused).For the distinction between the East as a utopia of production and the West as a utopia of consumption, see Susan Buck-Morss, “The City as Dreamworld and Catastrophe,” October 73 (July 1995): pp. 3–26. If the privatization of health care indeed had played an important role in the fusion of these two equally outdated materialist ideologies – like my personal story made me believe – then one could interpret the calendar SCHLAF 1992 as an early Neomaterialist articulation. Unlike art, however, this business gift wasn’t supposed to inspire; it was only supposed to promote a product in an aesthetic way. Who knows why they only depicted women or whether or not they were aware they were advertising a date-rape drug that causes amnesia in combination with alcohol. I assume the company’s publicity bureau simply attempted to communicate that the advertised drug was strong enough to make you fall asleep anywhere, anytime, no matter how uncomfortable your body position, no matter if you are safe.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Asleep I am both, neither active nor passive, neither waiting nor rushing, neither consuming nor producing; neither using nor being used. What I do is neither helpful nor egoistical, neither is it public nor private. Intuitively, I would certainly associate sleep with privacy. People tend regularly to withdraw from the streets, from the laptop, and from most other people, to turn to their own private sleeping berth as far as they have one. Sleeping is the one predictable activity for which an (inhabited) private home is used, where everybody with reliable access to either a bed of their own or a bed shared as a couple, has a zone to defend as private. But even if you don’t have access to any of that, you will sooner or later fall asleep anyway, no matter where you are. Privacy is an entitlement and it is also an architecture; but sleep is a material necessity for human beings, just as it is for other mammals. No one can really explain why, but your body keeps telling you regularly that it’s true.

Since the 1950s it has been known that during a sleep phase called REM – recurring about every ninety minutes – our eyes move rapidly and our brain is highly active, while all our skeletal muscles are completely relaxed. We are dreaming vivid dreams with paralyzed bodies. In the opposite sleep phase, slow-wave sleep (SWS), we can move, but we are difficult to wake and totally disoriented if woken up. It makes a lot of sense to say “I slept like a baby,” not only because we slept through most of our baby years but also because when asleep we are physically and mentally disabled animals, unable to protect ourselves. We cannot overcome the need to sleep, so we will never overcome the baby’s absolute disability. Approximately every twenty-four hours, in synch with the rotation of the Earth around its axis, we expect our daily return to baby state, and we prepare for it by removing our bodies from danger and disturbance as best we can.

In neuroscience, sleep is often compared to going offline. When we are awake, we are online: connected with the world via perception, attention, and communication. In this state, synaptic productivity is very high. “Our brains play receiver to countless packets of data,”See [Why we sleep](http://www.medicaldaily.com/why-we-sleep-shy-hypothesis-claims-our-brain-must-pay-price-learning-266726), accessed October 18, 2016. creating new connections between neurons and strengthening existing ones. But unlike the internet, which can potentially incorporate an unlimited amount of servers, connections, and data, the biochemical network of the brain has a limit. This implies that if the connectivity in the brain should continue to increase, soon there will be no more space for new connections. According to the Synaptic Homeostasis hypothesis (SHY),Giulio Tononi and Chiara Cirelli, “Sleep and the Price of Plasticity: From synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration,” Neuron 81, no. 1 (2014): pp. 12–34, [doi](10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.025). during deep sleep, as slow oscillations flood the brain, the overall synaptic strength is downscaled to a basic level. All synapses weaken equally, with the result that many of them disconnect and only the stronger ones stay connected. It is through this regular clear-up process that we maintain openness to learning new things. As the authors of the SHY put it: “Sleep is the price we pay for [neuronal] plasticity” – that is, the brain’s ability to modify its own structure.

But not all neuro-materialist approaches apply the Darwinist paradigms of extinction and survival. As much as deep sleep is said to free-up the “storage space” necessary for thought and memory to occur at all, it is also described as a highly productive process of memory consolidation. An established modelSee Neil Burgess, Eleanor A. Maguire, and John O’Keefe, “The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory,” Neuron 35, no. 4 (2002): pp. 625–41. suggests that new information, at first, is registered in the hippocampus – a small area of the brain shaped like a seahorse, allocated to the limbic system, also called the mammalia brain, or the center of emotion. While awake, all information – given that it was both recognizable and new enough to note in the first place – is stored there temporarily. During deep sleep the hippocampus finally goes “offline,” refusing all incoming signals, while its informational content is gradually copied to the neo-cortex for long-term storage – a younger layer of the brain, located closer to the outside of the organ. I don’t understand how this copying works, and it seems that neither do the experts really, but sharp-wave ripples observed in the hippocampus seem to have something to do with it. Somehow, these ripples influence those slow oscillations running through the cortex, which in turn trigger changes of synaptic strength in some neocortical networks. These structural changes then again influence the pattern of the slow oscillations – leading to a bioelectrical feedback loop, a memory replay.Yina Wei, Giri P. Krishnan, Maxim Bazhenov, “Synaptic mechanisms of memory consolidation during sleep slow oscillations, JNeurosci 36, no. 15 (2016): pp. 4231‒47, [doi](http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-15.2016).

After a while, however, the slow oscillations start gradually to speed up again. At some point, most parts of the brain are reactivated as are the sexual organs; the eyes start to move rapidly and we enter the REM-sleep phase. As we have just updated our experiences, values, and autobiographies, new connections between them get tested out playfully in the neo-cortex. Consciousness partly turned back on again, it is as if I’m invited to witness these processes through the splintered mirror of language and imagery, as if visiting the experimental cinema of my own memory production. During the first part of the night, the REM phase with its vivid dreams last only a few minutes, towards the end it lasts around forty minutes, taking up a major part of the cycle. The US inventor Thomas Edison famously disrespected this kind of activity. As he said in 1922:

“The person who sleeps eight or ten hours a night is never fully asleep and never fully awake—they have only different degrees of doze through the twenty-four hours. [. . .] For myself I never found I need of more than four or five hours’ sleep in the twenty-four. I never dream. It’s real sleep. When by chance I have taken more I wake dull and indolent. We are always hearing people talk about ‘loss of sleep’ as a calamity. They better call it loss of time, vitality and opportunities.”Thomas A. Edison, The Diary and Sundry Observations of Thomas Alva Edison. New York: Greenwood Press, 1948, p. 58.

Already in Edison’s time, the pseudo-natural logic of capitalism prescribed that workers must be granted recovery time to retain productivity. No money is to be made while workers sleep, so, for a capitalist, sleep can only count as recovery, if it is to be valued at all. Thought of as recovery, however, sleep is not producing value but only preserving it, so it should be reduced to the absolute bare minimum. What the American Dreamer Thomas Edison didn’t know, however, is that both fetuses and newborns spend around 75 percent of their sleep in REM.See [on sleep](http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/strange-but-true-less-sleep-means-more-dreams/). Their open, vulnerable brains have yet to learn everything about the world that their bodies are growing into, and all this information needs to find a structure, it needs actively testing out in order to find an appropriate place in the brain. Reorganizing memories, trying out narrative connections, experiencing old feelings, making unconscious decisions in the darkness of the connectome; all this could count as work, rather than recovery – work that not only babies need to do. But even had Edison known more about REM-sleep, his strong belief in discipline and progress might still have made him call sleep “a heritage from our cave days.”

Many of Edison’s business projects – among them the electrification of New York – helped to make use of the nighttime to attend to other, seemingly more modern and profitable activities than sleep. One of his more famous projects includes the development and patenting of the cinematograph. It is, therefore, a fitting coincidence that the movie theater, in its early days, was assumed to mirror the processes going on in the brain or, as the psychologist, Hugo Münsterberg put it in 1916: “The photoplay obeys the laws of the mind rather than those of the outer world.”Hugo Münsterberg, The Film: A psychological study. New York: Dover Books, 1970, p. 41. One could say that in the cinema the (non-existent) brain is turned inside out for everyone to see whatever they see, feel whatever they feel. Seated in a comfortable chair in a dark room, amidst a random group of other people, consuming a film, was supposed to resemble the nightly dream-state. But the “dream factory” of cinema was designed to produce things that are even more attractive than the useless, lonely, and easily forgotten REM phase – dreams that everyone can have for free. Thus, from a materialist perspective, the purpose of cinema was to appropriate the brains of producers and consumers alike in order to integrate both into the circulation of capital. Of course, like any other industrial synthesis, this kind of brain sell-out can also go terribly wrong, as shown in the horror film Videodrome,David Cronenberg (dir), Videodrome. USA: Universal Pictures, 1983. where a mad professor’s brain tumor turns into a dangerously attractive virtual world.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In digital capitalism, it’s not the cinema or TV, but rather the omnipresent internet that is now supposed to obey the laws of the mind, making sleep appear more unproductive than ever before. Not only are we paying for internet access, electricity, fitness and recreation, but we enable companies to make money each time we communicate with someone, each time we click on something, navigating our precious attention through the internet. The more we use the internet, the farther the frontier of privatization moves into our embodied minds. In her historical study on the myth of the American Frontier and the economic practices that it was based upon, Patricia Limerick described Western history as an “array of efforts to wrap the concept of property around unwieldy objects.”Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The unbroken past of the American West. London and New York: Norton, 1987, p. 71. Now, these unwieldy objects include moments, friends, feelings, locations, activities, and articulations of all kinds. Gmail and Facebook are available free, because I pay with my attention, my interaction, with the content and the metadata of my life. In this attention economy, sleep is a break in data production. Only if I use a mobile sleep-tracking app that senses the vibrations on my mattress, to record and analyze my sleep cycle – with the promise that it will improve the quality of my sleep – can I keep contributing to the digital economy. Otherwise, as I doze off, the screens of laptop and mobile phone go black. Asleep, I finally turn all of my attention, or non-attention, to my own materiality, my intra-net.

In the meantime, a new research field called Critical Sleep Studies emerged in the Anglo-American world.For an overview of [Critical Sleep Studies](https://lareviewofbooks.org/review/sleeps-hidden-histories), accessed October 18, 2016. One of the core observations discussed there, is that a vast amount of people in the US – or with Jonathan Crary in “Late Capitalism”Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late capitalism and the ends of sleep. London: Verso, 2013. – suffer from sleep disorders. Even if they would like to spend their time with the reproductive labor of sleeping, their embodied minds refuse to collaborate. In capitalism, however, this is not necessarily bad news. On the contrary – from an economic perspective any physical or mental disorder is a wilderness that can potentially be civilized for a profit.

In The Slumbering Masses, anthropologist Matthew Wolff-Meyer shows that what we consider healthy and normal sleeping behaviors are not nature-given, but an effect of the disciplinary measures of capital. Over the course of the twentieth century, sleep cycles were installed, discovered, utilized, and so was the discourse around them. Compared to the early 1990s, for example, when the medical discourse largely ignored sleep, the amount of self-care and worry dedicated to maintaining healthy sleep cycles has risen significantly in the last twenty years. According to Wolff-Meyer, in the US, this transition is an effect of the direct-to-consumer advertising of sleep-inducing medications starting in the 1990s, which was accompanied by campaigns to popularize sleep as a health problem.Matthew J. Wolf-Meyer, The Slumbering Masses: Sleep, medicine, and modern American life. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012, p. 100.

Just around the time that direct-to-consumer-advertising of sleep aids became legal in the US, the giant calendar SCHLAF 1992, a pharmaceutical company-to-doctor-gift, appeared in our home in Leipzig (in a country, however, where public advertising of pharmaceuticals is still illegal to this day). Now, more than twenty years later, the women depicted month-by-month on the pages look like bleak icons of a neoliberal era that was about to begin. Here they are, sleep-deprived, isolated, individual consumers, who know how to take care of their molecular cycles, who have taken the right pill . . . only at the wrong moment – but that is just the misogynist joke of the calendar. These women have plugged their embodied minds into the semi-public space of science and capitalism. This space is not public in the political sense, because its purpose is not to facilitate articulations. It is a corporate, privatized space, produced by pharma®. Pharmaceutical products are not the same as regular commodities. They are more substantial than commodities, many of them are literally substances – intended to become part of your body and to transform your embodied mind. Produced to sell at a profit, a pharmaceutical product is truly successful if it forces you to consume this drug for the rest your life, which it, in return, helps you to prolong. If an antidepressant, for example, actually cured you of depression, it would be a rather unsuccessful product, being that a cured patient is effectively a lost customer as far as the health care market is concerned. In the same way, successful sleeping pills and stimulating drugs help to maintain the disordered sleep cycles that they are supposed to level and normalize.

A sleep aid, once supplied, becomes a supporter of the sleep disorder but one could also ask what it is, that causes these disorders in the first place? In 24/7, art critic Jonathan Crary casts a dystopian vision of round-the-clock-availability, interconnectivity, and constant exposure to screens laying ruin to both our sleep and our sensory skills. The book deals with a society where overworked and self-employed Americans are checking their emails several times a night and, as a result, are increasingly required to buy sleep in pill form. Sleep appears as an endangered physical and mental state, a prehistoric Lost World, finally, just about to be, conquered by Late Capitalism, while remaining incompatible with it at the same time. Trying to defend sleep against the capitalist attack, Crary characterizes it as “a periodic release from individuation – a nightly unraveling of the loosely woven tangle of the shallow subjectivities one inhabits and manages by day.”Crary, 24/7, p. 126.

Obsessed with the idea of withdrawal, Crary turns sleep into a separate space, ready to serve as a container for everything that capitalism fails to be. He claims: “In the depersonalization of slumber the sleeper inhabits a world in common, a shared enactment of withdrawal from the calamitous nullity and waste of 24/7 practice.”Crary, 24/7, p. 126. This fantasy of a sleeping “world in common” signifies a political pessimism quite typical of critics living in a society that they find unable to influence. The communal ideals that one has practically already given up on are projected onto an endangered world that is just about to be colonized and destroyed. Ironically, though, Crary’s Romanticism is very much in tune with Thomas Edison’s idea that sleeping is lazy and unproductive. Only the judgment is reversed and the assumed unproductivity is valued as a gesture of withdrawal.

Sleep is a material practice and a physical necessity, but this does not mean that it presents us with a world in common or a release from individuation. Even though communist thinking continues to disappear from national policies worldwide, we don’t need to project the notion of communality onto paralyzed bodies and disoriented minds. Just like any other political structure, a world in common has to be actively constructed and then maintained, and most of this work will have to be done during the wakeful hours, consciously and responsibly. So the real problem with Crary’s late capitalist subject is not that they are sleep-deprived, but that they have come to believe that there is no other way than to give in and devote their whole day to the “nullity and waste of 24/7 individualism.” At work and in public, you find yourself unable to engage in communality as a livable social experience, then finally in your bed at home, you long for consciousness to fade away so you will be haunted by a “world in common,” a neomaterial world just as unknown as it is unreliable. If consciousness, again, refuses to fade away, you are left to consider this painful lack to be at least contemporary.

If I should describe the state to which I periodically return when withdrawing from the world of wakefulness and attention, it would not cross my mind to associate it with communality. Sleep, to me, is clearly an experience of isolation. Throughout the different stages of the sleep cycle, I’m temporarily granted various disabilities that stop me from communicating with others and from engaging in the community. But whether one otherwise engages in service, care, sex, creative, management, protection, or technical work, none of us leaves capitalism when falling asleep. As Rob Lucas described in his essay “Dreaming in Code” he sometimes continues to solve code problems while asleep – labor from which the company he works for will directly profit. Lucas uses his own experience to describe how the minds of technical workers are habitually entangled with the power structures they are working within. He concludes: “if labour becomes a mere habit of thought that can occur even in sleep, then it would seem mistaken to place many revolutionary hopes in the nature of this mental work and its products, in the internet or in ‘immaterial labour.’”Rob Lucas, “Dreaming in Code,” New Left Review 62 (March‒April 2010): p. 132. Obviously, there is no such thing as immaterial labor. Even if I am not using my muscles to work I am using my nervous system; I use this very material tool called the brain.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Still, sleeping is different from being awake and the materiality of my brain is not accessible to me in the same way as other tools. In What should we do with our brain?, philosopher Catherine Malabou argues that, as we are not conscious (enough) of our neuronal plasticity “we are still foreign to ourselves, [. . . .] ‘We’ have no idea who ‘we’ are, no idea what is inside ‘us.’”Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008, p. 3. During sleep, this contemporary form of alienation manifests again in an almost tragicomical manner. In the very moment that I turn my attention toward my brain’s plasticity, my consciousness fades away and I am left out – again! But then, for no obvious biological purpose, at the end of a sleep cycle, some parts of my consciousness temporarily turn back on again at the end of the sleep cycle. I am invited to witness some of my brain’s unconscious workings as through a splintered mirror, a dream state in which I have no control, but neither does anyone else. The whole experience is free, but I don’t get to keep the products of my creative labor. Everything can change, but there is no one else there to share the change with me. This sounds a bit like a post-apocalyptic neoliberal utopia, but it’s just me working like a baby. Temporarily, I can devote all of my attention to the mirror-room of the self and the reproductive labor of self-care. And as I wake up – let’s say I slept well – I leave my relative isolation and return my attention to a world in common, the world of objects, or to an other – to someone different from me.

This essay is a revised version of a previously published article, “Sleeping in Public,” How to Sleep Faster #5 (Winter 2014/15).