© Nikos Katsikis

Operational Landscapes and the Planetary Thünen Town

Urbanization organizes the planetary terrain—not just through cities and agglomeration zones, but also through the totality of diffused production areas and global commodity chains. On the basis of a metageographical analysis, urbanist Nikos Katsikis portrays the extensive transformation of the planetary terrain through the assembly of operational landscapes into a functional “Hinterglobe.”

“Imagine a very large town, at the center of a fertile plain which is crossed by no navigable river or canal. Throughout the plain the soil is capable of cultivation and of the same fertility. Far from the town, the plain turns into an uncultivated wilderness which cuts off all communication between this state and the outside world. There are no other towns on the plain. The central town must therefore supply the rural areas with all manufactured products, and in return it will obtain all its provisions from the surrounding countryside. The mines that provide the State with salt and metals are near the central town which, as it is the only one, we shall in the future call simply ‘The Town.’”Johann Heinrich von Thünen, Isolated State. An English Edition of Der Isolierte Staat [1826]. Translated by Carla M. Wartenberg. Edited with an Introduction by Peter Hall. Oxford: Pergamon, 1966, page 1.

So opens German economic geographer Johann Heinrich von Thünen’s famous treatise “The Isolated State.” Developed during the early nineteenth century, von Thünen’s model aims to address the optimal organization of agricultural land around a single settlement, based on a combined calculation of production costs, land rent, and transport costs to the market (“the Town”). The resulting spatial configuration is a series of concentric rings surrounding the Town, the sole center of exchange (fig. 1). Closest to the Town lies a zone of intensive agriculture where farmers produce perishable goods such as dairy products and vegetables. Interestingly, the second ring is a zone of forestry, since wood was at the time the main fuel and construction material, and certainly heavy and difficult to transport. The third ring is dedicated to extensive cropland (wheat, corn, and potatoes). Further out lies the last zone, comprising pasture for the grazing of animals, which after a point becomes financially unsustainable to cultivate and eventually turns into wilderness, which in turn prevents all potential exchange with other towns. This “frontier” defines a closed but “complete” subsistent system, which even predicts the mining operations necessary for the provision of metals and salt (important for food preservation and storage at the time). Mines are conveniently positioned “close to the Town” in order to not disturb the location of the single settlement or the concentric land-use pattern around it.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

In von Thünen’s model we find one of the most prototypical, and also persistent, models of the metabolic relationship between a city and what has been often referred to as its “hinterland.” The model can be seen as a microcosm: a generic, but complete, pattern of self-sufficient geographical organization, based on specialized land use, bound and structured around a nodal agglomeration. This organization directly reflects a particular social and spatial division of labor: the Town is dependent upon the surrounding hinterland for its supply of food, construction materials, and energy, and the hinterland is dependent upon the Town for manufactured goods and services. The generic structure of the model allows an initial foregrounding of a particular interpretation of urbanization: it is revealed as a mode of reciprocal, geographical organization. The existence of the Town organizes and produces the landscapes around it, without which the Town would not be able to exist in the first place. Agglomeration and hinterland are two sides of the same coin connected through exchange, which is, again, only meaningful through, and dependent upon, the specialization of the human occupation of the Earth.

But although it is helpful to conceptualize urbanization as a condition of geographical organization, the closed, self-sufficient metabolism that von Thünen’s model suggests has long been surpassed, if it ever existed. The model’s geographically contiguous, local hinterland mostly reflects the settlement structures of pre-industrial societies, which even von Thünen’s age had already left behind. In fact, even in the preindustrial era, this metabolic model would have presented a strong simplification: interregional, long-distance trade has always been an important factor in the organization of human settlement, and local, contiguous hinterlands have always coexisted with more extensive metabolic flows linking cities and regions. The past two centuries, however, have seen a complete explosion of the geometabolic interdependencies of urbanization, under consecutive waves of capitalist development and the associated advancements in transport and communication technologies.David Harvey, "Cities or urbanization?." City 1.1-2 (1996): 38-61. The shifting and continuously globalizing spatial divisions of labor have interwoven an increasingly globalized meshwork of production landscapes into the global system of exchange, leading to new forms of concentration of population and economic activity in growing agglomeration zones, and also to the expansion of their metabolic support into a multiscalar array of global hinterlands.

Still, the generic nature of von Thünen’s model allows us to start sketching this planetary organization of capitalist urbanization through a conceptual experiment: the Isolated State could be conceived as a micrographic conceptualization of nothing less than the entire world. The Town of the model corresponds to the universe of agglomeration areas, while the hinterland of the model corresponds to the totality of productive landscapes that support them. An initial visualization of this thought experiment is reflected in the map of figure 2: the global system of all areas of concentrated settlement of all sizes (from towns to cities to larger metropolitan areas and agglomeration zones) is plotted in orange, against the totality of the used part of the planet, shown as a dark background.Based on a compilation of the following datasets: “Global Human Settlement Layer,” European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2016, http://ghsl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/; K.-H. Erb et al., “A Comprehensive Global 5min Resolution Land-Use Dataset for the Year 2000 Consistent with National Census Data,” Journal of Land Use Science, vol. 2, no .3 (2007), pp. 191–224; Vector Map Level 0 (VMap0) dataset, US National Imagery and Mapping Agency, 1997. Taken together, the “Planetary Thünen Town” covers no more than 3 percent of the total used land area of the planet (around 3,000,000 km2). The majority of the used land area of the planet, then—the extensive dark mass that covers almost 70 percent of land surface (around 100,000,00 km2)—corresponds to landscapes of primary production, such as agriculture, grazing, forestry, and mineral extraction, as well as of circulation and waste disposal.

This other 97 percent of the used area of the planet, these “operational landscapes” of planetary urbanization, which traditionally has been considered to constitute the hinterlands of cities, has also been undergoing intense transformations under globalized urbanization, leading to the increased specialization and regional decoupling of these landscapes. Building upon the agenda of planetary urbanization, urbanization is here revealed as a dialectical relationship between what has been framed as “concentrated urbanization,” broadly referring to agglomeration zones in their various forms, and “extended urbanization,” including the operational landscapes of agricultural production, resource extraction, circulation, and waste disposal.This contribution is part of an ongoing research project on the operational landscapes of planetary urbanization, developed with Neil Brenner at the Urban Theory Lab, Harvard Graduate School of Design (www.urbantheorylab.net). Major literature on planetary urbanization agenda includes N. Brenner and C. Schmid, “Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban?” City, vol. 19, nos. 2–3 (2015), pp.151–82; N. Brenner and C. Schmid, “Planetary Urbanization,” in M. Gandy (ed.), Urban Constellations. Berlin: Jovis, 2011, pp. 10–13; N. Brenner, Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization. Berlin: Jovis, 2014; and N. Brenner, “Theses on Urbanization,” Public Culture, vol. 25, no. 1 (2013), pp. 85¬–114. What is the essence of urbanization is not the condition of concentration per se, but rather the condition of geographical interdependency that emerges out of it. It is through the globalized interdependency between agglomeration landscapes and these extensive operational landscapes that urbanization organizes the planetary terrain.For an initial framing of the concept of operational landscapes, see Nikos Katsikis, “The ‘Other’ Horizontal Metropolis: Landscapes of Urban Interdependence,” in Paola Viganò, Chiara Cavalieri, and Martina Barcelloni Corte (eds.), The Horizontal Metropolis Between Urbanism and Urbanization. Berlin: Springer, 2018, pp. 23–45.

Unfortunately, urbanization is often solely associated with the production of one type of landscape: the “urban fabric,” corresponding to densely built up, densely populated settlement spaces. Urban growth is often considered to unfold with the expansion of this urban fabric over that of agricultural, forest, or other landscapes. But, in fact, while urbanization might be in some areas consuming productive landscapes, it is at the same time also producing them elsewhere in the world. Since 1900, settlement areas have increased in size more than four times, following a similar growth in population, but at the same time, agricultural areas have also expanded more than two times, and their operationalization has likewise been highly intensified to support the growing metabolic pressure.Kees Klein Goldewijk et al. “The HYDE 3.1 Spatially Explicit Database of Human‐Induced Global Land‐Use Change over the Past 12,000 Years,” Global Ecology and Biogeography, vol. 20, no. 1 (2011), pp. 73–86. Following the relationship between the distribution of population and the operationalization of the planetary terrain perhaps offers a more useful indicator in understanding urbanization as geographical organization, as compared to the typical understanding of urbanization as the growth and expansion of cities. That is, for most of the nineteenth century, and up until the mid-twentieth century, population grew slower than the expansion of used land (land of all sorts, but predominantly agricultural land), whereas since the 1950s, the rate of population growth has been consistently higher than the expansion of used land. To simplify this general observation: the period up to the 1950s could be characterized as a period of expansion, leading to declining overall densities (fewer people on average over used areas), and we could call the current period, starting in the 1950s, a period of intensification, with more and more people depending on a very slowly expanding and deeply intensifying set of operational landscapes. In sum to say, as the metabolic frontier of the Planetary Thünen Town has been closing down, more intensive and specialized modes of operationalization have been proliferating in order to support it.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

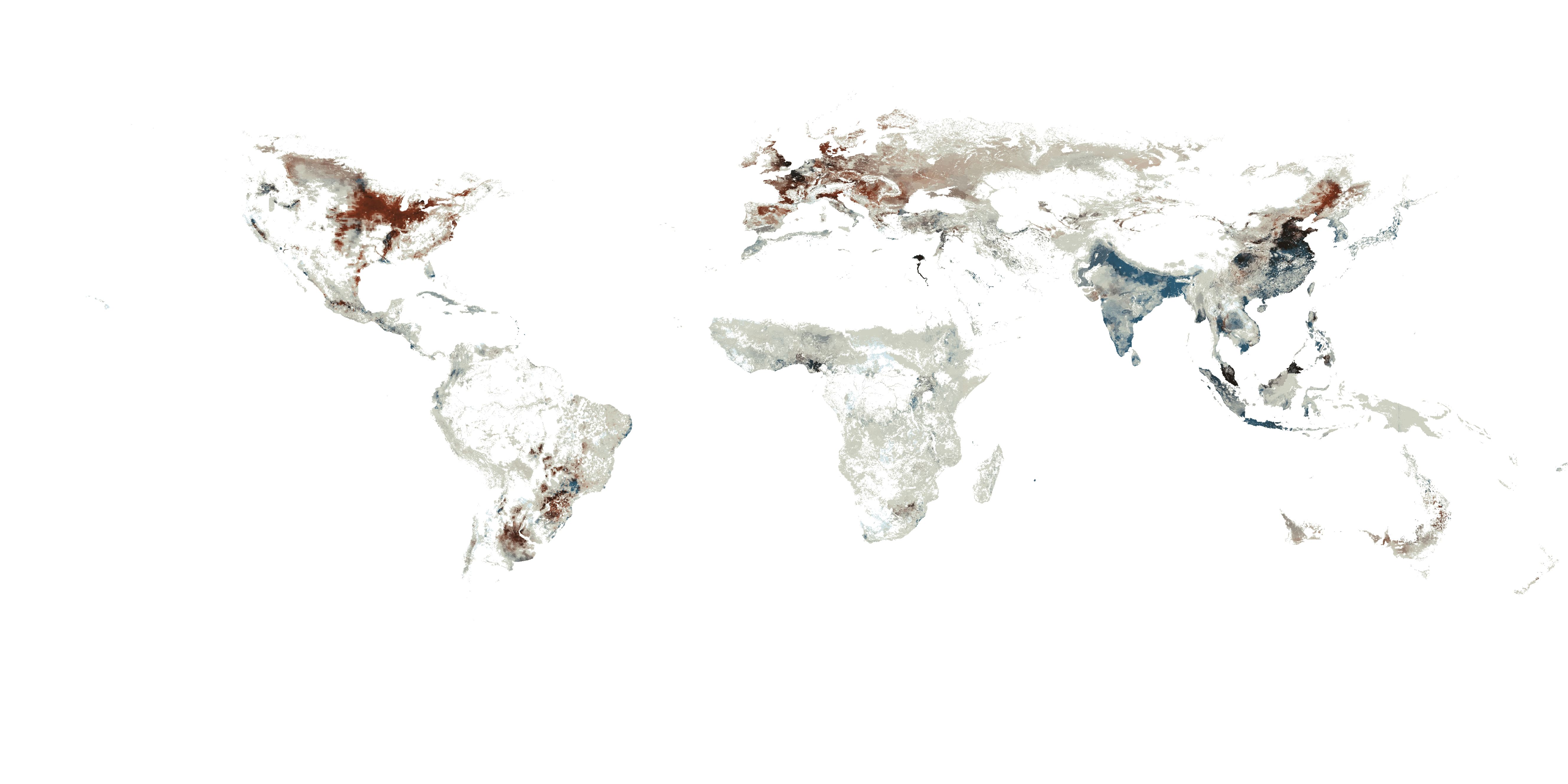

But what is of utmost importance is that the contours of this operationalization have been largely uneven around the world. The map in figure 3 offers a largely impressionistic effort to grasp the variation that characterizes the contemporary condition of planetary urbanization, deconstructing the dichotomy between the agglomerations and the “exterior” dark pattern presented in figure 2. This interpretation aims to reveal the asymmetrical distribution of population, infrastructure, built land, and productive land. Population densities (in blue gradient) are weighted upon the density of transportation networks (red gradient) and built land (red gradient), as well as upon densities of productive land, cropland, forest, and grazing pasture (green gradients). A further synthetic animation summarizes the major arguments. This scheme starts to uncover the rich complexity of configurations and the great unevenness in the distribution of equipment, population, and productive land, but of course is still unable to address the complex socioecological tensions that underlie their configuration.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

Indeed, assuming the universal applicability of this simplified model of the Planetary Thünen Town, even through this more complex visualization, entails the risk of homogenizing the extremely uneven conditions and processes that shape the landscapes of urbanization across the Earth. This is a risk very similar to the problematic effect of the Anthropocene debate in concealing the complex socioecological tensions that underlie the era’s undeniable transformation:Paul J. Crutzen, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” in Eckart Ehlers and Thomas Krafft (eds.), Earth System Science in the Anthropocene. Berlin: Springer, 2006, pp. 13–18. The Anthropocene does not reflect the impact of humanity on the planet but rather the ways in which capitalist development, as the dominant mode of development, has been interweaving social and natural systems over at least the past two centuries. The Anthropocene could be in fact better conceptualized as the Capitalocene: an era in which consecutive waves of capitalist urbanization have been organizing both society and nature in the search for profit.Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London Verso Books, 2015. The landscapes of the Capitalocene, interwoven with the geometabolic landscapes of planetary urbanization, can thus be conceptualized as landscapes of a profit matrix.David Harvey, The Limits to Capital. London: Verso Books, 2018. While in Thünen’s model the relationship between the Town and the hinterland is defined by the optimal allocation of land and transport costs, in the age of planetary urbanization, the configuration of agglomerations and operational landscapes is defined by the search for profit. And while in Thünen’s model the relationship between the Town and its hinterland is local, geographically contiguous, and direct, the search for profit in the age of planetary urbanization has exploded the relationship between agglomerations and operational landscapes into geographically discontinuous, globalized, specialized, and indirectly interlinked configurations.

Discontinuous and Globalized

With the continuous division of labor under capitalism, the chain of production and the labor processes involved in the production of almost every commodity grow exponentially. In most globalization debates, this horizontal organization of global production networks through complex commodity chains has emphasized mostly the reorganization of the top sectors of the economy—that is, the global relocation and reorganization of manufacturing (accompanied by the exploding trade in intermediate products)—and the associated globalization of the tertiary sectors of the economy, especially management and financial activities. However, together with the globalization of manufacturing and service sectors, another globalization has been taking place, one that has remained largely invisible: a globalization of the primary sectors of the economy, which is much more significant for the reshuffling of global metabolic patterns. Since the mid-twentieth century, the production and circulation of primary physical commodities (agricultural and mining products, fuels, and construction materials) has been growing exponentially.

Since the 1950s, while population has grown less than three times, global material extraction (biomass, fossil fuels, minerals, construction materials) has grown almost five times, from around 15 billion tons in 1950 to almost 70 billion tons in 2010. At the same time, trade in primary commodities has grown more than twelve times, from 900 million tons in 1950 to 10 billion tons in 2010. Only around 6 percent of production was globally traded in 1950, while in 2010 it was closer to 15 percent.For global trade statistics, see Ricardo Hausmann et al., The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014; and United Nations Comtrade (Commodity Trade) Database, http://comtrade.un.org. For global material extraction and global material flows data, see F. Krausmann et al., Growth in Global Materials Use, GDP and Population during the 20th Century,” Ecological Economics, vol. 68, no. 10 (2009). This globalization of the primary sectors of the economy has been interwoven with a splintering of the metabolic basis of urbanization, as previously local and geographically contiguous hinterlands have dissolved into a globalized meshwork of global production and logistical networks. Of course, not all metabolic flows have been delocalized, and not all operational landscapes have been globalized. But even systems with direct geographic delimitations (such as water supplies of cities) are being continuously stretched, as agglomeration zones expand and more and more physical commodities become part of global commodity chains.

Specialized

As operational landscapes of primary production have become increasingly integrated into global systems of exchange, they have also become excessively specialized. And while specialization in the production of primary commodities are to a considerable degree linked to the specificities of natural geography, the comparative advantages of natural geography have are also interwoven with the effects of economies of scale, regulatory frameworks, corporate practices, and geopolitical interests. The concentration of the majority of the production of a series of physical commodities in certain regions around the world creates a system of “core operational landscapes,” which are responsible for providing the material basis of all layers of production that are based upon them, similar to the way that certain global cities play a decisive role in commanding the top sectors of the economy.

Like the concentrations of fossil fuel and natural gas deposits across Venezuela, North America, Russia, Nigeria, and the Gulf countries, agricultural commodities such as corn and soybeans are also excessively concentrated. The Corn Belt in the United States produces almost 30 percent of all corn and soybeans; adding in the southwest regions of Brazil and the northwest regions of Argentina brings the number to almost 50 percent of all global production. Industrial crops, which are necessary inputs for a series of industries, are also extremely concentrated. For example, palm oil is almost exclusively produced across Borneo and Sumatra in Indonesia and Peninsular Malaysia, and cotton is more than 50 percent produced in China (along the Yangtze River Basin and the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain) and India (mostly in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh). Similar specializations characterize the extraction of minerals and construction materials. More than 50 percent of all aluminum production in the world is taking place in the Henan and Shandong provinces of China, while almost 50 percent of all copper has been extracted in northern Chile and southern Peru. At the same time, the region of Western Australia is extracting almost 30 percent of all iron ore in the world.UN Comtrade Database, http://comtrade.un.org.

Agglomerations zones are no longer dependent on their specific regional hinterlands for their supply; rather, global operational landscapes eventually offer the metabolic basis for several, even all, agglomeration zones in the world. Rendering the model of the city and its respective hinterland obsolete, the contemporary metabolic condition could be more accurately conceived as an extended, operational, specialized matrix of operational landscapes, interwoven through a continuous exchange with a multiscalar matrix of concentrated settlements.

Indirectly Interlinked

The metabolic exchange along this matrix—between agglomeration landscapes and operational landscapes—becomes increasingly indirect with the increasing division of labor and the complex organization of commodity production into lengthy commodity chains. The question of defining the hinterland of the city as a linear relationship, becomes not only methodologically challenging but conceptually restrictive. An obvious example is the food supply of a city. The production of almost any type of food has become a process consisting of multiple steps, whereby the output of every process becomes the input for the next, until the chain reaches consumption. The two extreme ends of all these processes can indeed be reduced to a simple interpretation of the city - hinterland model: the one end, the very basic extraction process, is connected to the exploitation of natural resources from the land; the other end, the final steps of the consumption process, are connected to the areas of high population concentration—the city. All the intermediate steps, however, involve a multitude of different spatial configurations that can be located across a multitude of sites. Next to the cultivation area there can be an initial processing or storage facility, which can then be connected to a further processing facility, which can most likely be located in a city, which however might not be the final destination of the commodity produced. It might instead be exported and consumed in another city (in the case of a finished product) or become the input for a new cycle of processing. In this case, the hinterland of a city could very well be another city. And the supply zone of a hinterland could be a city or even another hinterland.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The map in figure 4 highlights this indirect interrelationship of operational landscapes with agglomeration landscapes and with each other, showing in two gradients the cropland dedicated to direct food production (blue gradient) and to the production of animal feed (red gradient). Out of these gradients, only the landscapes dedicated to food production could be somehow considered more directly connected to agglomeration zones, where food is actually consumed. The other production system actually provides inputs not for direct consumption but to other industries, which could be themselves located in other operational landscapes around the world (such as the feed directed to the livestock industry).

As more and more landscapes of primary production are integrated into globalized systems of capitalist production and commodity exchange, they become part of a profit landscape. The constant pressure to renegotiate their social, technical, and natural capacities in order to offer bundles of profitable commodities to the global markets leads to increasing industrialization, and equipment, and intensive monofunctional operationalization, but also to forms of social and ecological exploitation and eventually exhaustion. At the same time, due to the nature of extractive economies, these operations are still deeply grounded in the specificities of natural geographies. This particular characteristic—the high degree of rather monofunctional activities in the absence of high population densities—can be in certain cases observed as an evolving tendency, linked to ongoing processes of mechanization and automation of primary production. With the continuous thinning of these landscapes’ settlement patterns, their economic diversity is dissolved, turning them into more and more “machinic” elements of the production of primary commodities. As these operational landscapes dissolve and the traditional urban metabolism of the hinterland transforms into a globalized system of production networks and global commodity chains, social relationships are also reduced into a purely economic exchange. As urbanization generalizes this condition of geographical interdependency, operational landscapes expand and intensify the construction of a globalized shared landscape assembly. Instrumentalized through global commodity chains, this planetary operational totality signals the shift from the universe of fragmented localized hinterlands to the totality of the Hinterglobe.For a further elaboration of the concept of the Hinterglobe, see Nikos Katsikis, “From Hinterland to Hinterglobe: Urbanization as Geographical Organization” (PhD diss., Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2016).