Source: Flickr

Renee Barron 2010

Anthropotechnics for the Anthropocene

What if we understand the technoscientific world we live in as a result of certain cultivations of the self? How might we turn this understanding into new trainings and techniques of thought, of feeling, intuiting, and acting? Historian John Tresch looks at the history of modern science from the angle of spiritual athleticism, ascetic practices and epistemic virtues, examining the possibility of grappling with the existential conditions of the technosphere in ways that might be considered “wise.”

1. Wisdom Techniques?

“Wisdom” is a word with an erratic valence, used much less often these days than, say, “knowledge,” “skill,” or “science.” It’s not something one can formally seek to learn or develop—you can’t take a degree in “Wisdom Studies.” At the same time, the very awkwardness that one feels in preparing to stand up in public to talk about it suggests that “wisdom” remains something that is valued and even powerful—a rare quality you should approach only with a respectful caution.

Following “wisdom” with the term “techniques,” however, does seem to bring it into reach. “Wisdom techniques” suggests wisdom may be a goal one can attain through deliberate action—a result not only of grace but also of work. It also seems to bring to the surface a condition that implies a detachment from ordinary affairs, at a contemplative distance from the pulsing, grinding, squealing, and beeping welter of machines and systems in the various states of integration and functionality that make up our world ‒ some shiny, bright, and connected, some rusting, failing, and ignored.

That ambiguous juxtaposition makes the present exploration a search not for answers but, in a very speculative and experimental mode, for questions. For example, what might be the place and meaning of wisdom in the contemporary world? What techniques seem to embody or produce it? How do these stand in relation to other techniques or technologies?

The last question is particularly acute when we think of the contemporary planet as a “technosphere”—a mesh of apparatuses and mechanisms of different scales and materials woven into the body of the Earth, in which human ideas and motivations have driven explorations, fortifications, and incessant research. A world of scaffoldings and rigs, of social and technical organizations which are inseparable from the orders of nature—inseparable from forests and fields and bedrock, inseparable from the oceans and atmospheres that surround us.

Taken this way, the technosphere may be another way of talking about the Anthropocene, the proposed geological age where human industry has transformed the Earth for millions of years to come. However, the technosphere focuses attention on the space in between human ideas and the forces of the nonhuman world: it leads one to concentrate on technologies for transforming exterior milieus, such as the industries of oil extraction, splitting atoms, and building and powering engines. It also points to technologies of knowledge, including telescopes and microscopes, scanners, experiments, and simulations.

Yet I wish to propose a discussion of “techniques” of a more intimate nature, of a physiological, psychological, mental, and even spiritual form; techniques that concern also the interior milieu: the skilled practices that humans have devised and applied to train and reshape themselves. These can be called “anthropotechniques” (Sloterdijk, at least, uses this term – it’s not my invention).

These include ascetic disciplines, gymnastics, types of yoga, and other structured patterns of action which transform less the external world than the body and the mind. Such practices become habits, which in turn set the backdrop for any “technology” or “knowledge.” Humans must be shaped into the kinds of beings who can build and make; who can receive and create knowledge. Given the many years before children are able to operate semi-autonomously in the world they inherit—training, Bildung, “la formation,” conditioning, is inescapable in the human condition.Clare Carlisle, On Habit. London: Routledge, 2014.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Most training of this sort aims at making sure that business continues as usual. However, mixing forms of training from one branch of learning with another is also the basis for novelty, for extending experience, endurance, perception. Historians of science have studied how new laboratory apparatus produces new objects and new relations, manifesting latencies and virtualities, stabilizing phenomena. Likewise, new self-disciplines can tap into, redirect, and transform what the philosopher William James called “the energies of men.”William James, “The energies of men,” Science 25, no. 635 (1907): pp. 321‒32; Francesca Bordogna, William James at the Boundaries: Philosophy, science, and the geography of knowledge. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008. Thus, “wisdom techniques” calls to mind techniques of transformation and discovery not only in the external world but also in the internal world. This therefore means openness to older, often forgotten forms of knowledge, which fall into categories that may seem a long way from “global warming” and “environmental change”: these include self-help, spiritual practice, and religion.

It is reasonable at this point to wonder what exactly a history and speculative exploration of bodily and mental practices have to do with the Anthropocene? Why this line of thinking, when what we need are concrete technical innovations ‒ or new forms of aesthetic representation ‒ or political strategies to allow experts, citizens, and even polluted oceans, disappearing species, and shrinking ice caps, to be heard above the usual clamor over national security and monetary profits?

Of course, we do need to work on technical and scientific, artistic, and political forms to address the environmental breakdown caused by runaway consumption. Nonetheless, the Anthropocene names a situation so multifaceted, fast-changing, and unpredictable that the usual forms of problem-solving and expert advice are insufficient. The roots of the situation lie beyond the domains of the natural sciences: they can be found at the level of human political and economic organization, but even more fundamentally, in the habits of thought, feeling, and action, in imaginations, cravings, commitments, attitudes, relationships with nature, views of the good life, and of what’s possible.

There cannot be a single solution for a “super wicked problem” like this. Instead, the question is how each of us, caught in the groove of our own training and experience, can deviate from our usual track sufficiently in order to hear and build upon the message coming from another track, or perhaps forge a new one.

Additionally, we need new ways of sensing the relationships we already hold, yet which remain invisible or outside our consciousness. These are the relationships, for example, between staying in the dark or switching on a light, driving or taking public transportation, relationships between our desire for comfort for ourselves and our families and friends, and the production of greenhouse gases and the filling up of the landfills.

But awareness of these relationships often takes place at a level prior to representations ‒ whether arguments, facts, or even striking artistic realizations: instead, now, it’s at a level of sensing invisible connections, learning to register their impact without words, even without symbols. Perhaps they even require new senses and modes of attunement.

The question is how to sink new perceptions and attunements into the body and the mind and make them hold. An essential point about disciplines and anthropotechniques is that they are not a one-time thing, not a single event: they are long-term, even a life-long training, with heavy demands on personal time and patience. They are about testing—as in Benedict Spinoza’s phrase—what a body can do.“No one has yet determined what the body can do.” See Benedict de Spinoza, A Spinoza Reader: The Ethics, and Other Works, ed. and trans. Edwin Curley. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994; Gilles Deleuze, Expressionism in Spinoza, trans. Martin Joughin. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992. What happens if we repeat this phrase, if we maintain this pose, if we pay attention to our breathing, and quiet our thoughts; what if we visualize this form for just a little longer? What experience awaits us, what new way of being? What new flexibility or sensitivity becomes possible after repeating these courses of training, after making them daily habits?

Such techniques pass outside or beyond the communication of facts ‒ possibly even beyond practical skill, or even prudence and phronesis. These techniques are about knowing with expanded and deepened senses—some of which may be beyond the verifiably biophysical. They may involve knowing not just what to do and say, but how to refrain from action, when and how to remain silent, how to weigh different ways of knowing, and adapt them to shifting demands. They may even help develop something like the “wisdom” in this contribution’s title. This may seem like a new way of talking about science, technology, art, and religion but, actually, it is also among the oldest.

2. There are no Religions and Science is one of Them

Philosophers and sociologists are acutely aware of this dimension to life: Émile Durkheim talked about the physical and emotional habits behind collective representations; Marcel Mauss’ “bodily techniques” (combined with readings of Thomas Aquinas, Erwin Panofsky, and Martin Heidegger) inspired Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of “habitus,” a structure of trained dispositions. Michel Foucault drew attention to the bodily discipline applied to individuals and populations at the intersection of human sciences, surveillance techniques, and institutions for training and reform. He later gave these disciplines a more positive spin, examining “techniques of the self” practiced by ancient philosophers to produce “ethical subjects” of themselves ‒ including introspection, journal writing, visualization, and proscriptions on diet, sleep, sex, and speech. This updated Friedrich Nietzsche’s obsession with the bodily origins of ideas and attitudes, including the violent mnemonics that created humans as “an animal which can promise.”Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. Joseph Ward Swain. Mineola, NY: Dover, 2008[1915]; Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977; Marcel Mauss and Nathan Schlanger, Techniques, Technology and Civilization. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006; Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism. Latrobe, PA: Archabbey Press, 1951; Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1977; Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 2: The use of pleasure. New York: Vintage Books, 2012; Friedrich Nietzsche,. On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo, trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books, 2010; see also André Leroi-Gourhan,. Gesture and Speech. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

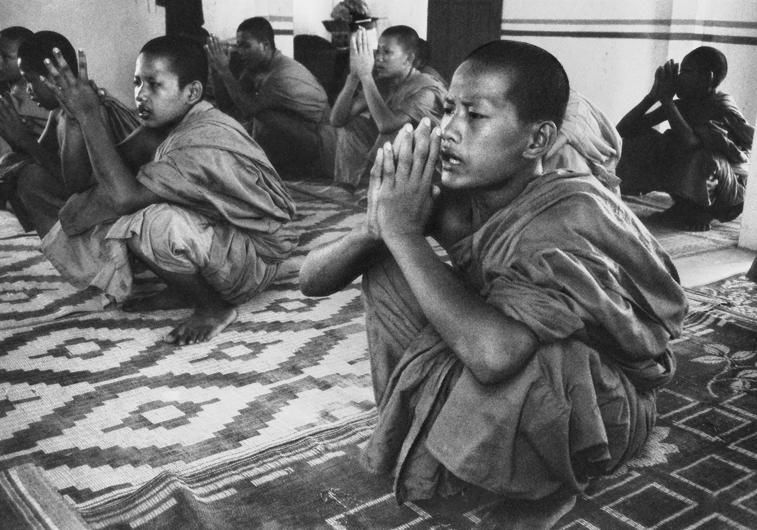

A more recent effort is Peter Sloterdijk’s You Must Change Your Life.Sloterdijk, Peter, You Must Change Your Life, trans. Wieland Hoban. Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2013. Here, Sloterdijk proposes a new take on modernity, in fact on human history, retold through the story of “anthropotechniques” or method of training routines and disciplines. His argument dusts off some old notions such as Karl Jaspers’ Axial age—the era, starting around 500 BCE, when new religions and philosophies appeared worldwide laying emphasis on individual ethics and transcendence.Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History, trans. Michael Bullock. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 1953; see also Bronislaw Szerszynski, “From the Anthropocene Epoch to a New Axial Age: Using theory fictions to explore geo-spiritual futures,” in Celia Deane-Drummond, Sigurd Bergmann, and Markus Vogt (eds), Religion and the Anthropocene (forthcoming). For Sloterdijk, this decisive epoch in the history of world civilizations was the result ‒ as every great leap in the capacities and definition of the human has been ‒ of new anthropotechniques. New trainings in ascetic and spiritual techniques, such as fasting, meditation, and the development of attention, require stepping out of the ordinary flow of the river of existence.

For Sloterdijk such training is the source of the most important innovations in the history of humanity. He gives one of his chapters the provocative title: “No religions exist” ‒ there are no religions. His audacious claim is that what we take to be essential to religions ‒ credos and narratives about creation and the afterlife, moral codes, symbols, rituals, and institutions ‒ actually are secondary phenomena. They all appear after the founding act of any religion, which is when some individual pushes farther and more fiercely along the tracks of some new training routine and arrives at an otherwise inaccessible truth or insight into reality. Returning to the collective with an incomprehensible account of these other realms, his awestruck followers translate these elusive realities into the elaborate scenographies of harmful spirits, ancestors, deities, and saints; that is, the moral prescriptions and rites which make up the objects of religious scholarship.

According to Sloterdijk, the heroic accomplishments of these spiritual athletes transform the course of history by pointing to new and difficult routes toward which even ordinary people can strive. They offer new horizons, which often take the form of a goal of liberation from everyday life into an “otherworld” or a “beyond.” He doesn’t advocate any single training, insisting that there is no one true path forward, and certainly no fixed end point to reach. Each course of practices and habits is a largely blind striving toward well-marked plateaus, and beyond them, toward untested and previously unknown peaks of “Mount Improbable.”

Combining and merging distinct practice traditions has brought about new techniques in training, which further enrich the course of history: Francis of Assisi’s saintly path, for instance, joined monastic renunciation with the naturalism and romantic emotionalism of courtly love poetry. Ignatius of Loyola fused the monastery’s prayer and devotion with knightly training in combat and self-sacrifice, forging a guiding example for the Counter-Reformation.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Sloterdijk acknowledges a debt to Foucault (the other prominent twentieth-century philosopher who took Heidegger’s attempts to articulate the variable houses of Being as an imperative to study spaces, technologies, and bodily practices), but laments the excessive attention Foucault paid to prisons, asylums, and hospitals. Instead, for Sloterdijk the most important actors for turning all of humanity into spiritual athletes, into monks of both transcendent and worldly orders, were the great early-modern theorists of pedagogy and instruction. His main example is John Amos Comenius, the seventeenth-century Moravian who laid the foundations for modern mass education. The builders of schools had far wider and deeper effects on the transformations of humanity than the builders of prisons did ‒ although both added to the store of methods for making and remaking bodies in order to create new minds.

There is something refreshing about Sloterdijk’s retelling of the emergence of the modern technosphere in terms of spiritual practices and training regimes, and his call for widespread research into anthropotechniques. He sees an entirely new field opening up through the collection and comparison of techniques which all cultures possess—and which form the real basis of their differences, far beyond genetic differences. Yet his own book only draws lightly on the practice traditions of other cultures, which in many cases are far more developed than any in the West.

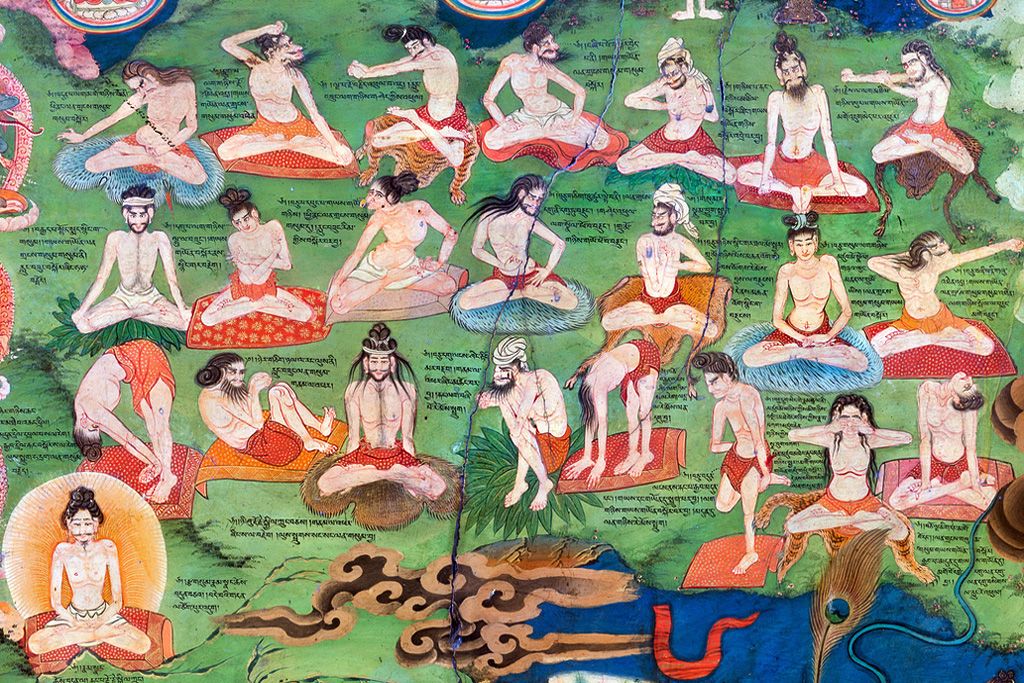

For instance, the Hindu Shastras, including the Arthashastra, Dharmashastra, and Kamashastras as well as Yogashastras, all inventory techniques for maximizing wisdom, pleasure, and ability to rule over others by ruling over oneself. Likewise, as in the Lukhang retreat, a temple built by the fifth Dalai Lama in Lhasa in the seventeenth century, Buddhist traditions preserve vast arsenals of physical and contemplative practices aimed at loosening attachment to the self and cultivating insight into the non-duality of objects and subjects, mind and matter.The Lukhang retreat, recently introduced in an exhibition held at London’s Wellcome Collection: [“Tibet’s secret Temple”](https://wellcomecollection.org/secrettemple), accessed October 26, 2016. At the Lukhang temple, these practices are ordered like items in a library, depicted on the image of the mural seen here as a reference manual for things one might do to, with, and for oneself; the energies and deities one will encounter along the way; and the transformations to expect on the other side.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Western scholars of religion have had a tendency to focus on religious beliefs, symbols, representations, or social organizations, evacuating the power and undermining the epistemic claims of spiritual practices. Further, even when such trainings are translated to the West, often there is a neutralization of their ethical content and wider frames of experience and reference. Take for example consumer-friendly yoga or secularized “mindfulness” training, which offers instruction for developing moment-to-moment attention through repeated exercises but in many cases without the ethical framework of the right action, right speech, and right livelihood, and often without the end-goal of liberation. While “mindfulness” has exposed millions to ancient Buddhist practices, it has often done so by grafting it to other trainings aimed at marketing and management.Stefanie Syman, The Subtle Body: The story of yoga in America. New York: Macmillan, 2010; Andrea R. Jain, “Mystics, Gymnasts, Sexologists, and other Yogis: Divergence and collectivity in the history of modern yoga,” Religious Studies Review 37, no. 1 (2011): pp. 19‒23; Linda Heuman, [“Don’t Believe the Hype,” tricycle](http://tricycle.org/trikedaily/dont-believe-hype/) accessed October 28, 2016; Norman Farb, “From Retreat Center to Clinic to Boardroom? Perils and promises of the modern mindfulness movement,” Religions 5, no. 4 (2014): pp. 1062‒86; Joanna Cook, “Mindful in Westminster: The politics of meditation and the limits of neoliberal critique,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6, no. 1 (2016): pp. 141‒61.

This observation is in line with the long course of development Sloterdijk traces in Western modernity, which he does with some help from Max Weber.Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism and Other Writings. New York: Penguin, 2002. Western asceticisms have followed a long journey, traveling from ancient routines of gymnastics and philosophy-as-a-way-of-life, to the hothouse of the medieval monastery, and from there, with the dissolution of monasteries during the European Reformation, out into the world. From the early modern period, various ascetic kits went on to redefine individual and collective practices of war, politics, scholarship, arts, and sports. The drive for habits of self-control and self-transcendence continues, even after the primary goal of salvation has faded: it now takes the form of a general athleticism, adopted by nation-states or imposed in neoliberal markets, in which it has become everyone’s personal responsibility to adopt some form of practice as a means of “wellness.”

large

align-left

align-right

delete

large

align-left

align-right

delete

3. Anthropotechnics of the Sciences

Yet the West has made its greatest impact on the planet through its scientific and industrial attainments. There seems to be, then, an important oversight in Sloterdijk’s story—one with great relevance for the technosphere. Despite all the work of science studies and histories of science, there remains a powerful tendency to consider science as a body of facts, theories, or attitudes—rather than in terms of its practices and concrete settings. Beyond focusing our attention on these external factors, we might also re-conceive the history of science in terms of the physical and mental disciplines—many of them first elaborated in the monastery and convent—to prepare knowers for acquiring and maintaining bodies of knowledge and to allow for their expansion and modification.

What would a history of science and technology look like if told through the history of training routines, disciplines, and individual and collective anthropotechniques? How might we study technoscience, not as a set of theories, facts, or even (as in much recent work) as institutions, objects, and technical apparatuses, but as a set of disciplined explorations into the potential capabilities of both researchers and their objects, as expeditions from the base camp of Mount Improbable, combined and recombined? We would have to expand Sloterdijk’s formula: there are no religions, and science is one of them.

The medieval monastery would necessarily continue to play a central role in this genealogy. Here, techniques of the vita contemplativa in ancient philosophy were integrated into a form of collective life at an astounding pitch of intensity, where every thought, act, and breath was to be directed toward the single goal of salvation. This was the testing ground of manuscript culture and its scholarly habits, as well as the repetitions and trainings of the trivium—including rhetoric’s topoi and theaters of memory, later renewed as a core of self-cultivation practices in the Renaissance. The quadrivium’s habits of measurement and comparison (in astronomy, mathematics, geometry, and music) were also later grafted onto the skilled routines of craftsmen—a key step in the emergence of mechanical philosophy and its combined epistemic, technical, and moral aims.Jean-Claude Schmitt, “The Rational of Gestures in the West: A history from the 3rd to the 13th centuries,” in Fernando Poyatos (ed.), Advances in Nonverbal Communication: Sociocultural, clinical, esthetic and literary perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1992, pp. 77‒98.

Even in the “scientific revolution”—supposedly the moment of a decisive breakaway from the religious past and towards modern materialism—spiritual practices form a strong through-line. Practices associated with “the good life” and “ascetic virtue” were central to modern natural philosophy in the cultivation of courtly manners, in the habits of detached discernment, and plain speech embodied by Robert Boyle, as well as in Isaac Newton’s habits of self-denial, in line with his idiosyncratic researches into alchemy and biblical history.Steven Shapin, “The Philosopher and the Chicken,” in Christopher Lawrence and Steven Shapin (eds), Science Incarnate. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1998: pp. 21‒50.

Similarly, René Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy, an indisputable source for mechanical philosophy, traces an otherworldly narrative before arriving at the world known to science. It begins with the philosopher retreating from the world around him into an isolated cell, then, step by step, the removing of all familiar reference points, including any input to his senses until he contemplates of only “clear and distinct” ideas: his own thinking soul, the perfection of God, the truths of geometry. Yet while the text clears the path for mechanical science, its model is the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola and the multiday retreats which all Jesuits had to undertake, which strengthened their faith through mnemonics and practices of clear and distinct visualization. Modern science emerged, in part, by rewriting monastic scripts for self-transformation.Matthew L. Jones, The Good Life in the Scientific Revolution: Descartes, Pascal, Leibniz, and the cultivation of virtue. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

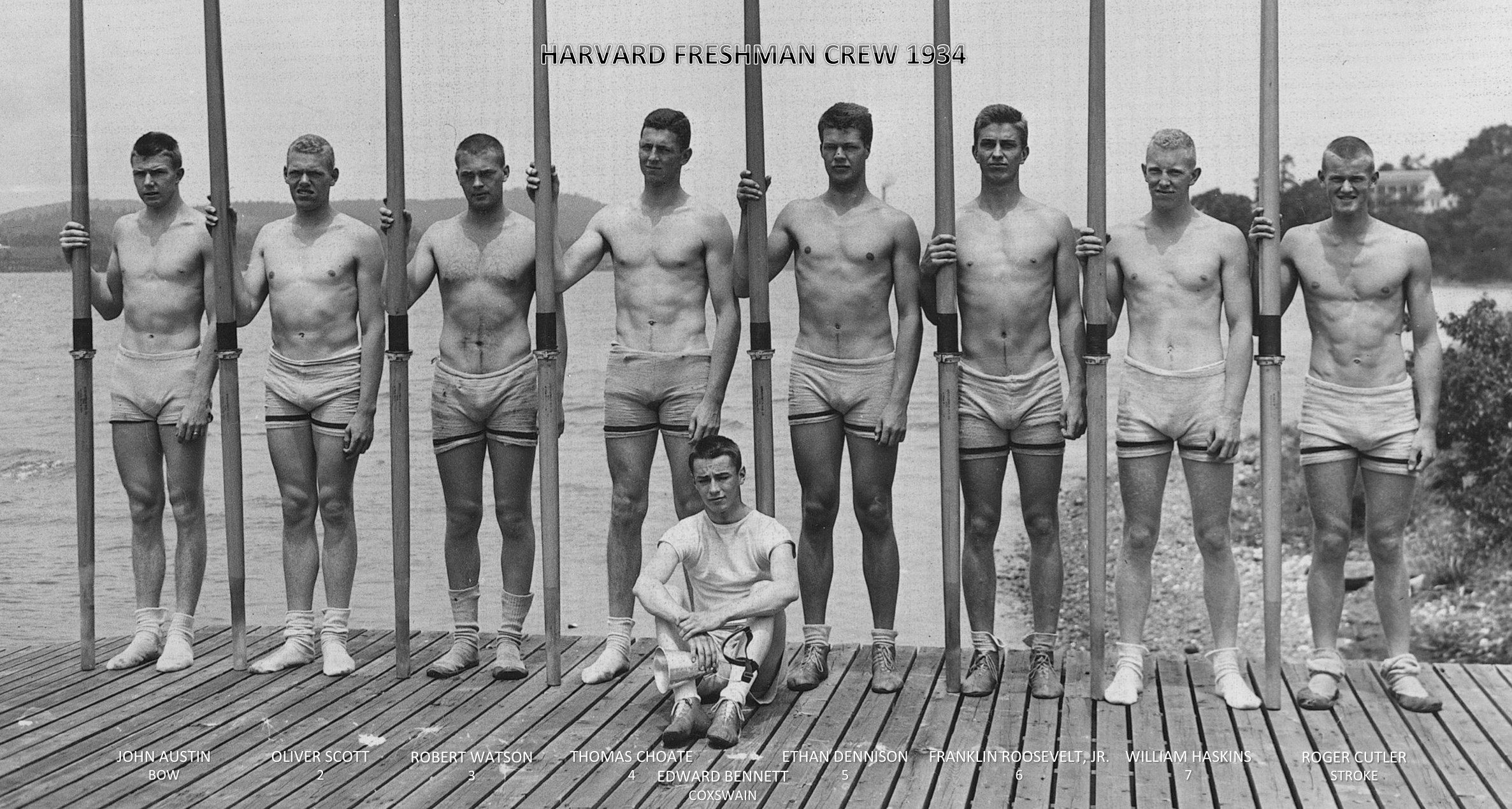

As historians of science Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have shown an important part of modern “objectivity” is the “epistemic virtues” and routine habits of mind and body through which individual knowers discipline themselves. Eighteenth-century mathematics training continued the repetitions and writing habits of monasteries, and moved them out into the world in the form of surveying, mapping, and engineering. In nineteenth-century Cambridge, the new mathematics curriculum, which was administered with common drills and meticulously repeated proofs, in a setting that combined fraternal solidarity with individual competition for the prize of being named “Wrangler,” unfolding in perfect resonance with the gymnastics training, running, and crewing that mathematics students undertook.Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity. New York: Zone Books, 2007; Andrew Warwick, Masters of Theory: Cambridge and the rise of mathematical physics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

The reformed research universities of the late nineteenth century and the new American universities such as Johns Hopkins borrowed from the Humboldtian model the ritual of the seminar and the disciplined repetitions and bricolage of the laboratory. Yet, these disciplines now were tied to new gymnasia and playing fields, the new stadiums where the skills and virtues of the lab director and administrator were echoed in those of the quarterback. This was even more bluntly the case at the West Point Military Academy—the institution into which blackboards were first introduced in the United States, for math and engineering, then for football training, which led to scenario-projection in War Rooms.William Clark, Academic Charisma and the Origins of the Research University. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2006; Larry Owens, “Pure and sound government: Laboratories, playing fields, and gymnasia in the nineteenth-century search for order,” Isis 76, no. 2 (1985): pp. 182‒94; Christopher J. Phillips, “An Officer and a Scholar: Nineteenth‐century West Point and the invention of the blackboard,” History of Education Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2015): pp. 82‒108.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

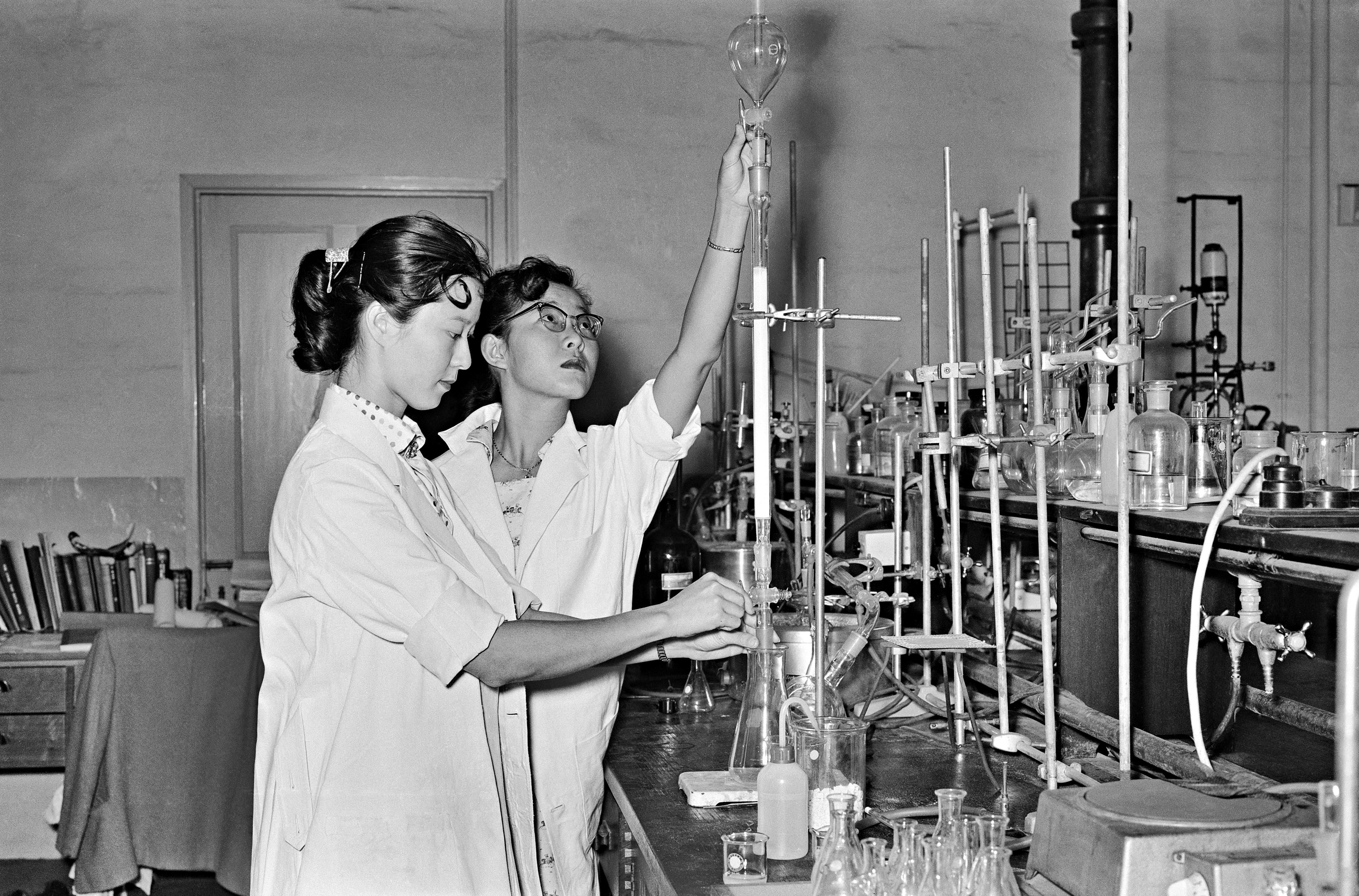

Clearly, such genealogies continue into the present, but with modifications. What kind of anthropotechnics of knowledge are we inculcating now? What are the training routines, administered in schools or on individual courses of study, which are producing virtuosic scenario-planners, data-miners, algorithm designers and “value-creators”? How do the bureaucratic habits of bioethics and internal review boards create an ethics of research, and in what ways do they prevent others from arising? What techniques now drive our training in programming, in working with probabilities, in forecasting, in choosing among various competing models, in evaluating experts, and choosing from among entirely different forms of expertise?

large

align-left

align-right

delete

The pursuit of such inquiries into the anthropotechniques of scientific knowledge could give us a grip on a crucial strand in the contemporary technosphere—one which we must grasp in order to have any hope of unraveling its current state, or of re-weaving it into less self-destructive forms. In broader terms, the question is something like this: Through what techniques and disciplinary kits have humans produced the kinds of people capable of making scientific discoveries and technological innovations, of building on past discoveries and pushing them farther, of instituting them and extending them until they form the net of facticity and technical control which now seems inescapable?

Furthermore, what aspects of this training and practice have made people so blind when it comes to foreseeing the critical damage brought by wide-scale industrialization, so deficient when it comes to grappling with the true causes of climate change, so powerless at redirecting the headlong path toward geocide (or something close to it) upon which we seem embarked? What practices have trained not only scholars and citizens but also the experts who help direct our societies, to focus on a single problem or domain and its short-term solutions, while they ignore its side effects and unforeseen consequences?

4. Monasteries of the Future

Finally, such questions bring us back to the task we set ourselves at the outset: to imagine and institute new anthropotechniques. Not to replace those currently in practice, but to combine with them, in order to create subjects—ourselves, first of all—capable of sustained awareness and orientation toward the relations and consequences of our acts, and those of our lawmakers and other powers, upon the well-being of all Earth’s inhabitants.

I end with questions, not answers, returning to the place we began. What training can provide the ground for instilling and renewing the attitudes, motivations, and impulses that interrupt the status quo, in our own routines, and those of others? What new monasteries and training sites might we institute, to form subjects capable of responding thoughtfully and competently to expertise and to intuitions—and even to wisdom—which reaches us from beyond the narrow pathways set by our earliest training regimes? What new ways of being alone together— the paradox at the etymological root of “monastery”— might allow more compelling sensitivities to our inescapable interdependence to take root?

Revised from a talk given during the Wisdom Techniques investigation at the Technosphere × Knowledge event at HKW, Berlin, April 16, 2016.