© Agostino Iacurci, 2018

Vladimir Vernadsky and the Co-evolution of the Biosphere, the Noosphere, and the Technosphere

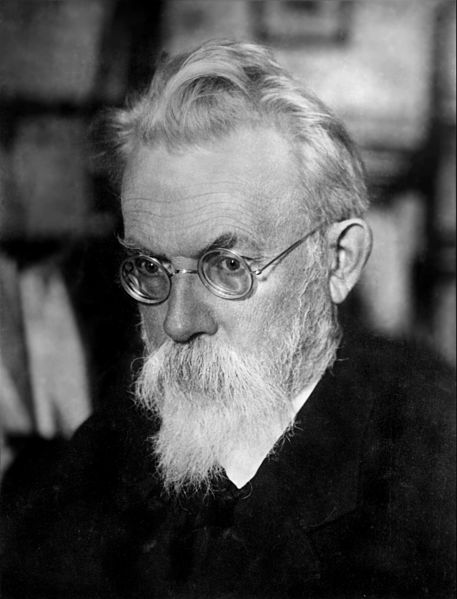

How did the current notion of “spheres” as an operational interface between living and inert matter come into being, and how did it go on to infiltrate thinking about the bio-techno-sphere, which today seems the best descriptive model for our own habitat? In this profound historical contextualization of the work and life of the eminent Russian naturalist Vladimir Vernadsky, historians of science Giulia Rispoli and Jacques Grinevald draw on the transformational role of concepts.

Two Faces of the Cosmos

In the introduction to the book Living MatterVladimir Vernadsky, Zhivoe Veshestvo. Moscow: Nauka, 1978. A more complete edition was published in 1991. An unpublished French text, “La matière vivante dans la biosphère“ dates from Bourg la Reine, November 1925., titled “Two faces of the Cosmos,” Vladimir Vernadsky described the main two conceptions that have permeated the scientific understanding of the universe. He pointed out that the first view of the cosmos was a mathematical, physical, and mechanical representation of it that can be grasped by human reason. Often epitomized by the works of Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, Isaac Newton, Leonhard Euler, and Pierre-Simon Laplace, this worldview excludes living organisms; thus, human beings have no place among all the “esoteric” physical elements and movements forming this material universe. This vision was foreign to us for it did not contemplate our role in the cosmos and all the interferences we can generate. No turmoil may come from humankind’s activity when considered with this mechanistic Weltanschauung. Therefore, such interpretation leads to an oversimplified theory of the cosmos, leaving out, for instance, a perspective from natural sciences, evolution, and energetics.

large

align-left

align-right

delete

Besides the classical, physical, and mathematically driven image of the cosmos there is another that is much more familiar to human understanding. This is not broken up into geometric shapes and, rather than addressing the whole cosmos, it refers to just a part of it—that is the Earth as an evolving planet, whose geological spheres have been thoroughly studied not only by physical geographers, but also by famous naturalists such as Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, or Eduard Suess. The epistemological novelty of this second worldview, says Vernadsky, consists mainly in the idea that our cosmos contains a natural phenomenon that is often overlooked in the purely physical and mechanical interpretation of it. This element is life, as opposed to entropy.

Soil as a Biogeochemical Sphere

These two competing views that Vernadsky faces in his analysis are not easy to integrate, especially if one takes into account that the physical image of the cosmos tends to diminish sacral aspects of the Earth that, in old Russian and peasant culture, are traditionally associated with its “maternal” living Nature. This tradition that finds its roots in the Russian and European Middle AgesCaroline Merchant, The Death of Nature. New York: Harper Collins, 1980. no doubt played an important role in the development of mining, metallurgy, mineralogy, geology, and early earth sciences; perhaps it also helps explain the exceptional interest in the study of the pedosphere that led Saint Petersburg University professor Vasily Vasilyevich Dokuchaev (1846–1903) to establish soil science (pedology) as a fundamental and applied scientific discipline. Dokuchaev’s systemic and genetic approach to the study of the Earth’s landscapes and his investigation of soil as a “global natural object” at the crossroad of chemistry, mineralogy, geology, meteorology, and biological sciences thoroughly inspired Vernadsky. The pedosphere is studied here in its genesis and formation as the soil changes with time under the action of several factors: mineral, climatic, and geological, and also biotic and anthropogenic. The novelty at the time of such a holistic approach relies on the study of soil not only for its geophysical and chemical composition, but also from the viewpoint of its microbiological functioning and evolutionary history. The pedosphere is not just a substratum made from the weathering of rocks; rather, it has also been formed by an amazing entangled diversity of plants, animals, and microorganisms over myriads of years. The same seems true with the world’s oceans through phytoplankton and marine biogeochemistry.

Conceiving nature as an entangled, complex system, Vernadsky affirmedIn line with other naturalists like his Ukrainian colleague Sergei N. Vinogradsky. the need for a more suited approach to explore the features of soil as a bioinert body and its essential role in the Earth’s biogeochemical regulation. Furthermore, Vernadsky contributed to the rise of Russian and Soviet nuclear research, being the leading promoter of radiogeology and radioecology.Georgy S. Levit, “Looking at Russian Ecology through the Biosphere Theory,” in Astrid Schwarz and Kurt Jax (eds), Ecology Revisited. Dordrecht: Springer, 2011 pp. 333–47. See also David Holloway, Stalin and the Bomb. London and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994, pp. 29–48 (“Nuclear prehistory”); Alexei B. Kojevnikov, Stalin’s Great Science. London: Imperial College Press, 2004; and Simon Inges, Stalin and the Scientists. London: Faber and Faber, 2016. This matrix of diverse scientific trajectories led him to intersect sciences of both inanimate and animate nature, making them converge into a new research pathway that he was to name “biogeochemistry” in 1923.

Living Matter goes Spherical

Vernadsky believed that the Earth as a whole is indebted to complex geobiological processes. An important part of his work is in fact focused on the emergence of a new notion: living matter. In depicting the importance of this massive biogeochemical force he did not simply sum up Earth and life, but elaborated on an integrative idea of their biogeochemical interaction, with living matter serving as an operational interface between them.Kiril M. Khailov “Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky: Originator of the Biosphere Concept,” La mer: Societe franco-japonese d’oceanographie, vol. 32 (1994): pp. 1–4. Vernadsky believed that the structure of living organisms is analogous to that of inert matter, although much more complex. Therefore, a living structure is not just an agglomerate of inert stuff; the difference seems to reside in dissymmetry and its energetic character, which cannot be compared geochemically with the static chemistry of molecular structures that are not able to reproduce themselves.Vladimir Vernadsky, The Biosphere. New York: Copernicus/Springer-Verlag, 1998.

Lying in the cyclical interaction of organic and mineral elements, living matter—through the photosynthesis of autotrophic plants—transforms solar energy into chemical energy that becomes available in the form of nutrients for other heterotrophic organisms populating the Earth. As Vernadsky claimed, the Earth’s surface is continuously shaped by the interaction between biological organisms and abiotic components, which forms its vital cycle. Vernadsky investigated living matter in the light of the geological evolution of the geospheres, namely the pedosphere, the hydrosphere, the lithosphere, and the atmosphere. As he explained:

“Living matter has a huge significance in the chemical history of the Earth’s crust. At every step, we run into his role in the establishment of minerals—a role that is very peculiar: living matter is a source of energy whose budget affects the natural chemical reactions, that is, the formation of minerals. It collects energy from the sun and turns it into chemical energy. In so doing, it proves to be a conveyor and a storage of cosmic energy.”Ibid.

Living matter, which is the sum of all organisms on Earth at any one geological time, is also described as a thin membrane covering the Earth. It tends to occupy all the space because it is a dynamic force in constant motion. This geological mass comprises living organisms, their products, parts of their decomposed bodies, their liquids, and so forth. It is the circulation of living matter that for thousands of years has contributed, and still contributes, to shaping the sphere of life, playing a crucial role even in the equilibrium of the whole Earth.

The Biosphere

The book that Vernadsky wrote in 1925 in Bourg la Reine, near Paris, is nowadays considered one of the first attempts to sketch out a comprehensive theory of the biosphere. The book, containing two parts: “The biosphere in the cosmos” and “The domain of life,” was entitled Biosfera and published in Leningrad in 1926. It described the sphere of life as a region of the Earth’s surface that is characterized by a specific thermodynamic field.Vladimir Vernadsky, “La structure chimique de la matière vivante et la chimie de l’écorce terrestre,” Revue générale des Sciences pures et appliquées, vol. 34, no. 2 (1923): pp. 42–51. Despite the novelty of the concept, Vernadsky had borrowed this term and the embryonic idea from Suess, who was referring to the biosphere as a zone above the lithosphere, connected with air and water that is limited in space and time and concerns only life and its unity on the Earth as a planet.Eduard Suess, Die Entstehung der Alpen. Vienna: W. Braunmüller, 1875, pp. iv–168; see also Suess, Das Antlitz der Erde. Prague and Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1909, vol. III, 2, pp. iv–789. Vernadsky’s account of the biosphere was much broader than the one proposed by the Austrian geologist. The Russian naturalist saw the biosphere as a holistic system placed in a cosmic framework, enabled and empowered by the Sun. The geological envelopes covering the Earth are part of the same biogeochemical process of the circulation of elements, but every layer has its own specific organization.

Innovatively, Vernadsky’s systemic and organizational perspective in the study of the phenomena taking place in the biosphere laid the ground for the birth of global ecology, an emerging environmental discipline studying the human impact on the Earth; the field acquired scientific status in the West with the ecological school of George Evelyn Hutchinson. Most importantly, Vernadsky’s biosphere theory seems to be, in a slanted, retrospective light, a historical antecedent to Lynn Margulis and James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis, for it underlined the role that the sum of all living organisms, as living matter, has had since its emergence and evolution in shaping the surface of the Earth to create the most suited environments for its spreading. As Lovelock pointed out, Vernadsky was the first scientist to make a general conclusion that living organisms as a whole take part, during all geological times, in the cycles of chemical elements, their evolution, and regulation. According to Lovelock, Vernadsky clearly recognized that there is a connection between life as a whole and the geological, chemical, and physical environment of the Earth as a singular planet in the Solar system. In this regard, Lovelock concluded, Vernadsky can be no doubt regarded as one of the “most illustrious predecessors”James Lovelock, “A Prehistory of Gaia,” New Scientist, vol. 111, no. 517 (1986): p. 51. of Gaia theory and the view of the Earth as system, which will be the driving notion underlined in the recent developments of Earth System Science.Jacques Grinevald, “On a Holistic Concept for Deep and Global Ecology: The Biosphere,” Fundamenta Scientae, vol. 8, no. 2 (1987): pp. 197–226.

According to Vernadsky, living matter has turned the Earth’s biosphere into a self-regulative, complex, bio-inert planetary system.Levit, “Looking at Russian Ecology through the Biosphere Theory,” 2011, p. 339. This is the case if we consider for instance the role of ozone—formed by three oxygen atoms (O3)—in the atmosphere, whose presence in the stratospheric ozone layer has made possible the absorbing of those harmful solar radiations that, if able to reach the Earth’s surface, would have destroyed life.The so-called “great oxidation” around 2.30 billion years ago was a major event in the coevolution of life, atmosphere, and Earth. Such an ozone screen formed from free oxygen is itself a product of life.Vernadsky, The Biosphere, 1998, p. 49. As in a positive feedback loop, life has increased possibilities for its own expansion over the terraqueous globe. Vernadsky saw life as the geological force par excellence that has determined the biogeochemical foundations and history of the Earth’s biosphere. In line with his conception of the coevolution of living matter and the changing face of the Earth, he also envisioned the power that civilized humankind would have had on the evolution of the biosphere before Chernobyl and Fukushima, and even before Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The Transition to the Noosphere

In Vernadsky’s view, the biosphere has to be conceptualized within a planetary, evolutionary framework;Jonathan D. Oldfield and Denis J. B. Shaw, “V.I. Vernadsky and the noosphere concept: Russian understandings of society nature interaction,” Geoforum, vol. 37, no. 1 (2006): pp. 145–54. Vernadsky is even recognized as a forerunner of astrobiology. As the evolution of our planet proceeds, the role of life becomes increasingly influential in its further destiny.Nikita Moiseev, et al., “Biosphere Models,” in R. K. Kates, et al., Climate Impact Assessments. SCOPE, 27 (1985): pp. 493–510. In this connection, Vernadsky devoted a great deal to the understanding of the intellectual and technological developments of human civilization in the biosphere. Inspired by several precedents and notably by Henri Bergson’s notion of Homo faber, he believed that human industrial activity, for instance mining and civil engineering, was having a major mineralogical and geological impact on the evolving biosphere and the circulation of elements across the entangled geospheres. He came to the conclusion that humankind was becoming able to modify the whole energy flow and all of its biotic and mineral elements. Homo faber was indeed transforming the face of the Earth, and expanding itself into every corner of the terraqueous globe; even outside it, within the cosmic space. As a matter of fact, other living organisms are confined solely to the geobiosphere, but humankind has been able to temporarily abandon its planet to explore a space beyond the Earth.

Vernadsky stressed that human agency was approaching planetary proportions, leading the Earth’s atmosphere to undergo a radical change in its chemical composition. To this regard, like Pierre Curie in his 1905 Nobel conference, he envisioned the threat of atomic war, the alarming scenario of the 1940s that would later be the object of investigation by the advocates of the “Nuclear Winter” theory, among them Paul Crutzen, the founding-father of the Anthropocene notion. To explain this new anthropogenic interference with biogeochemical processes and Earth history, Vernadsky introduced an additional sphere, the noosphere, to identify a new stage of the biosphere’s evolution in which the human mind, through scientific research and engineering development, becomes the main driving force for global environmental change in future-Earth history.Vernadsky developed his view in a book written in the 1930s, entitled Scientific Thought as a Planetary Phenomenon, which was posthumous, made available, in a censored form in 1978, and in a flawed English translation in 1997.

small

align-left

align-right

delete

The biosphere and the noosphere have to be considered as inseparable, interconnected systems that are crossed by a continuous exchange of biogeochemical and cultural processes. Human activity is indeed associated with the rise of a new form of energy that is not only biogeochemical but also, and at the same time, cultural. The exchange between the two spheres, however, does not compromise the specific autonomy of each one. Boundaries between them play an important role: Rather than obstructions or barriers, they act to increase the differentiation of sub-systems within a whole substantial unity.

Noosphere as a Bio-techno-sphere

Vernadsky was not the only one to introduce the notion of the noosphere. Edouard Le Roy developed this idea in complicity with his younger friend Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. They proposed to look at this stage as the last and ultimate one in the biosphere’s evolution. The noosphere is a culmination of a collective spiritual agent, a super-mind, which drives the Earth towards the Omega-Point.Georgy Levit, Biogeochemistry-Biosphere-Noosphere. The Growth of the Theoretical System of Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky. Berlin: VWB Verlag Für Wissenschaft Und Bildung, 2001.

Vernadsky’s conceptualization of the noosphere differed significantly from those advanced by the French Catholic thinkers. According to Vernadsky the problem of the origin of life was the problem of the formation of the Earth’s biosphere, therefore the impact of human consciousness on Earth was a question entirely rooted in the biosphere and its biogeochemistry. In contrast to a spiritual stage qualitatively separated from the biosphere, the noosphere, according to Vernadsky, marks the emergence of human technological and scientific activity as a geological phenomenon that is functionally and physiologically dependent on Earth’s mechanisms. Thus, the noosphere is a concrete material system that connects humankind and the planetary environment through science and technics, and whose processes can be traced back in the Earth’s geochemistry. The noosphere discloses a complex system in which all life, including man and its exosomatic instruments, the earthly environment, and all technologies became inseparable. In this respect the word bio-techno-sphere would be even more suited then technosphere to untwist the bundle underlying the Vernadskian notion of the noosphere.

As Vernadsky pointed out in his Problems of Biogeochemistry, in the course of the last half-millennium the development of civilized humankind’s strong influence over its surrounding nature, and its comprehension of it, continued growing ever more powerful and with an accelerating tempo.

“During that time the unified culture embraced all the surface of the planet (see § 64), the book printing became discovered, all earlier inaccessible areas of the Earth were recognized, new forms of energy (steam, electricity, radioactivity) were mastered, all chemical elements became coped with and used for human demands, telegraph and radio were invented, the drilling penetrated into the Earth’s crust for kilometers, and man rose with his aeroplanes to a height of over 20 kilometers from the surface of the geoid. [...] The question of the planned, unified activity for mastering nature and for the right distribution of the wealth is now on the agenda. This question is tied up with the consciousness of the unity and equality of all people, with the consciousness of the unity of the noosphere."Vladimir Vernadsky, Scientific Thought as a Planetary Phenomenon, Moscow: Nongovernmental Ecological V.I. Vernadsky Foundation, 1997, pp: 186-187. Vernadsky, “‘Problems of Biogeochemistry’ II: The Fundamental Matter-Energy Difference between the Living and Inert Natural Bodies of the Biosphere” (trans. George Vernadsky, ed. and condensed by G. E. Hutchinson), Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 35 (June 1944), pp. 483–517.

Was Vernadsky a precursor to the post-Second World War Holocene-Anthropocene transition? Probably not. It is true that he had already prefigured ethical issues deriving from the ecological imbalances of man’s engagement with nature in a time when ecological concerns were banished under the Stalinist regime; but Vernadsky was thus censored, deformed, or ignored until very recently. However, if on the one hand he believed that changes and accelerations in the human technical system of labor and production can cause geological phenomena of huge significance, on the other his noosphere notion seems to coincide with the fulfillment of a new morality, a new rationality, and eventually the emergence of a new humanism. This does not resemble the catastrophic tone of Crutzen’s Geology of Mankind or, more in general, the idea of the Anthropocene that constantly reminds us about the damaging effects that humankind has had on the environment since at least the thermo-industrial revolution of the mid-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Indeed, Vernadsky’s latest writings on the noosphere seem instead more optimistic with regard to humanity’s future use of scientific and technological knowledge.

By highlighting the importance of the study of coevolution between humanity and the biosphere from a long-term perspective, the noosphere unveils a more complex concept, in philosophical terms, and with a historical depth that precedes humankind’s most recent endeavors.Oldfield and Shaw, “V.I. Vernadsky and the noosphere concept,” 2006. We must remember also that Vernadsky’s geological thought was mainly Huttonian, and very different from the “Wegenerian revolution” (J. Tuzo Wilson) of the 1960s or the more recent neocatastrophism of mass extinctions and biodiversity crisis thinking. Understanding the noosphere calls then for a more comprehensive historical analysis, going beyond an explanation of the human degradation of terrestrial ecosystems, the so-called global environment, or sustainability.

Vernadsky’s holistic approach problematizing the relations between humankind, scientific and technological progress, and the Earth was overlooked by his contemporaries. This lack of intellectual and institutional support in the West (France, England, and the United States) was one of several reasons why Vernadsky decided to return to the Soviet Union, where he developed his biogeochemical studies within the Academy of Sciences. In the Stalinist State Vernadsky was respected as an international-class geoscientist and even honored, but not really understood; his social and philosophical ideas were repressed by communist ideologists. After his death, and at the beginning of the Cold War, Vernadsky’s ideas were banned and rehabilitated only during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika.

Vernadsky’s renaissance started in the 1960s, and the rediscovery of his biosphere–noosphere theory, the originality of his approach, and the charisma of his persona emerge vividly today, driving us through the intricate threads connecting the Anthropocene debate and the rebirth of the technosphere notion, but still able to fuel and enrich current controversies and narratives.